The History of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, 50 Years After Its Construction

Built in 1964, the span still stands as Americas’ largest suspension bridge

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/ba/9dba4210-8ae1-405b-98c7-1b1fc8efbca7/nov14_l04_phenom-verrazanobridge.jpg)

As long ago as 1910, when a steady parade of steamships bearing immigrants passed through the Narrows—the mile-wide channel at the entrance to New York Harbor—engineers envisioned a great bridge as a gateway to the New World. When it finally opened, 50 years ago this month, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge—honoring the 16th-century Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano, though not to the extent of spelling his name correctly—boasted the longest suspended span in the world: 4,260 feet, or four-fifths of a mile. Even after the great era of steamships had passed, the bridge held sway, dictating the design of the Cunard liner Queen Mary 2, once the world’s largest passenger ship, which first sailed in 2003, so that at high tide its funnel would pass beneath the roadway with 13 feet to spare.

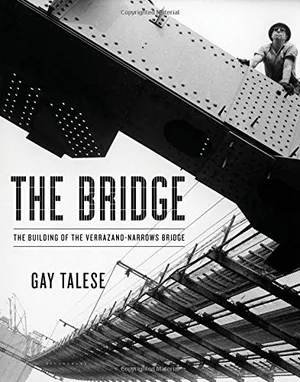

Connecting Brooklyn with Staten Island, it is still the longest suspension bridge in the Americas, 11th in the world. The crowning achievement of the structural engineer Othmar Ammann and of New York’s imperious master planner Robert Moses, it was built for $320 million (about $2.5 billion in today’s currency), more or less on budget, a standard of frugality that present-day New York can only dream of. Ten thousand men worked to build the bridge, from “punks” lugging heavy bolts to foremen dubbed “pushers” to John Murphy, the superintendent, whose temper and sun-and-wind-hardened face led his charges to call him Hard Nose behind his back. Three men died. The bridge’s construction was vividly chronicled by Gay Talese, then a cub re=orter for the New York Times, whose book, The Bridge, is now being reissued in an expanded edition by Bloomsbury. It tells of Mohawk Indian ironworkers who made a specialty of walking the high steel and of James J. Braddock, once a world heavyweight boxing champion (Joe Louis took his title), by then a welding machine operator. “The anonymous hard-hatted men who put the bridge together, who took risks and sometimes fell to their deaths in the sky, over the sea—they did it in such a way that it would last,” Talese recalls in an interview

When it was finished, a ride across cost drivers 50 cents, or the equivalent of less than $4. But we should be so lucky: Today the cash toll is $15. Old-timers still mourn the sundered neighborhoods of Brooklyn, where hundreds of homes were destroyed to make way for the approach, and the sleepy, almost rural character of Staten Island when it was linked to the rest of New York City only by ferryboat.

To Talese, the Verrazano is about more than transportation. “A bridge, in its ultimate form, is a work of art,” he says, and one can see his point. Sunlight glints off the pair of monumental steel towers, 70 stories tall, carrying the curvature of the earth into the sky, where their tops are exactly 15⁄8 inches farther apart than at their base. At night, lights pick out the graceful curve of the four great cables, each three feet in diameter, spun from enough steel wire to reach more than halfway to the moon. The bridge thrums with the traffic of a million and a half vehicles weekly, its passengers “suspended,” as the poet Stephen Dunn wrote, in 2012, “out over the Narrows by a logic linked / to faith.”