Hitler’s Very Own Hot Jazz Band

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120517020034joseph-goebbels-web.jpg)

Amid the collection of thugs, sycophants, stone-eyed killers and over-promoted incompetents who comprised the wartime leadership of Nazi Germany, Joseph Goebbels stood out. For one thing, he was genuinely intelligent—he had earned a doctorate in Romantic literature before becoming Hitler’s propaganda chief. For another, he understood that his ministry needed to do more than merely hammer home the messages of Hitler’s ideology.

Goebbels knew he needed to engage—with an increasingly war-weary German public, and with the Allied servicemen whose morale he sought to undermine. This clear-eyed determination to deal with reality, not fantasy, led him to some curious accommodations. None, however, were quite so strange as his attempts to harness the dangerous attractions of dance music to Hitler’s cause. It was an effort that led directly to the creation of that oxymoron in four-bar form: a Nazi-approved, state-sponsored hot jazz band known as Charlie and His Orchestra.

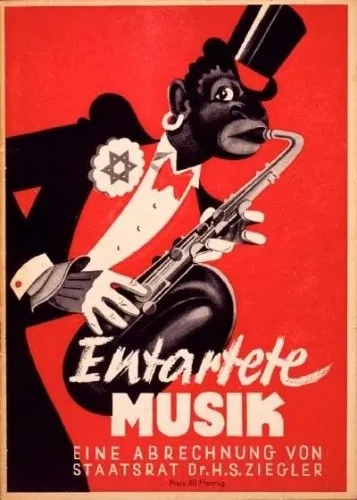

By the late 1930s, swing and jazz were by far the most popular music of the day, for dancing and for listening. But, originating as they did from the United States, with minimal contributions from Aryan musicians, the Nazis loathed them. The official party line was that these forms were entartete musik (“degenerate music”), and that their improvised breaks and pounding rhythms risked undermining German purity and discipline. In public speeches, the Nazis put it more harshly than that. Jazz, Goebbels insisted, was nothing but “jungle music.”

Throughout the war years, it was German policy to suppress the music, or at least tame it. This resulted in some remarkable decrees, among them the clauses of a ban promulgated by a Nazi gauleiter in Bohemia and recalled (faithfully, he assures us—“they had engraved themselves deeply on my mind”) by the Czech dissident Josef Skvorecky in the introduction to his novella The Bass Saxophone. They are worth quoting in full:

1. Pieces in foxtrot rhythm (so-called swing) are not to exceed 20% of the repertoire of light orchestras and dance bands.2. In this so-called jazz type repertoire, preference is to be given to compositions in a major key and to lyrics expressing joy in life rather than Jewishly gloomy lyrics;

3. As to tempo, preference is also to be given to brisk compositions over slow ones (so-called blues); however, the pace must not exceed a certain degree of allegro, commensurate with the Aryan sense of discipline and moderation. On no account will Negroid excesses in tempo (so-called hot jazz) or in solo performances (so-called breaks) be tolerated;

4. So-called jazz compositions may contain at most 10% syncopation; the remainder must consist of a natural legato movement devoid of the hysterical rhythmic reverses characteristic of the barbarian races and conductive to dark instincts alien to the German people (so-called riffs);

5. Strictly prohibited is the use of instruments alien to the German spirit (so-called cowbells, flexatone, brushes, etc.) as well as all mutes which turn the noble sound of wind and brass instruments into a Jewish-Freemasonic yowl (so-called wa-wa, hat, etc.);

6. Also prohibited are so-called drum breaks longer than half a bar in four-quarter beat (except in stylized military marches);

7. The double bass must be played solely with the bow in so-called jazz compositions;

8. Plucking of the strings is prohibited, since it is damaging to the instrument and detrimental to Aryan musicality; if a so-called pizzicato effect is absolutely desirable for the character of the composition, strict care must be taken lest the string be allowed to patter on the sordine, which is henceforth forbidden;

9. Musicians are likewise forbidden to make vocal improvisations (so-called scat);

10. All light orchestras and dance bands are advised to restrict the use of saxophones of all keys and to substitute for them the violin-cello, the viola or possibly a suitable folk instrument.

It is possible to trace the Nazi’s fear of jazz and swing back at least as far as the radical nightclubs of Weimar Germany (setting for the musical Cabaret), which Goebbels described in his diary as “a Babylon of sin.” But the Reichsminister also recognized, Horst Bergmeier and Rainer Lotz note, that “National Socialism set to music was not what most listeners wanted when switching on their radio sets,” and as the war years bit into German morale and bombs rained down on German cities, he began to make compromises that would have been inconceivable before 1939.

There was still reluctance to allow real American swing and jazz to be heard on the home front; Dr. Fritz Pauli of German state radio sketched the criteria for a “model dance band” that would have seemed alien to Glen Miller: twelve violins, four violas, brass, bass, drums–and a zither. Goebbels went further; he ordained that jazz be banned from the airwaves altogether, and all radio dance programs be prefaced by “a neutral march or overture.”

Behind the scenes, though, Hitler’s propaganda chief was hatching a plot: music deemed unsuitable for decent Germans was to be harnessed to help drive the Nazi war effort. Here Goebbels’s catspaw was a jazz fanatic named Lutz “Stumpie” Templin, a fine tenor saxophonist who had led one of the best German swing bands before the war.

Templin was an equivocal character; no Nazi himself, he had nonetheless taken full advantage of the opportunities that opened under Hitler’s regime. As early as 1935, what would become the nucleus of the Lutz Templin Orchestra ousted its Jewish leader, James Kok, in order to secure a recording contract with Deutsche Grammophon. By the autumn of 1939, Templin’s reputation as a sax player and his links to the Nazis were strong enough for the Propaganda Ministry to turn to him when it took the decision to begin piping musical propaganda to British troops.

Lurking in the shadow of the new initiative were William Joyce, the notorious “Lord Haw Haw,” an Irish-American employed by Goebbels to broadcast propaganda to Britain, and Norman Baillie-Stewart, another fascist turncoat whose chief claim to fame was being the last Englishman to be imprisoned in the Tower of London. They provided ideas, and perhaps some lyrics, to a former civil servant named Karl Schwedler, the man hired to front the crack jazz musicians who made up Templin’s band.

Schwedler was a remarkable character, a chancer and a chameleon well suited to thriving in the looking-glass world of Nazi Germany. Born the son of a plumber in Duisberg in 1902, he was a flawless English speaker who revealed an unexpected talent for crooning while working for the American section of the Foreign Ministry’s broadcasting department, Kultur-R. He was good enough at his job to earn exemption from military service on the grounds that he was doing “essential war work”—and to enjoy the protection of Goebbels himself.

Schwedler seems to have developed ideas above his station. According to Baillie-Stewart, “on a finger of his left hand he sported a massive signet ring engraved with a bogus coat-of-arms at times he even sported the Old Etonian tie until I mentioned the fact.” For much of the war, he lived a playboy’s life in Berlin, dressing in SS-monogrammed silk shirts and traveling widely, often to Switzerland, on the pretext of picking up the latest records and some new ideas. This gave him access to contraband (“silk stockings, liquor, soap, chocolates, cigarettes,” Baillie-Stewart recalled) which—combined with an easy charm—made his privileged position almost unassailable in an increasingly corrupt Third Reich.

The Templin Orchestra, renamed Charlie and His Orchestra in honor of its new vocalist, began broadcasting in January 1940 as part of a propaganda show known as “Political Cabaret.” Mike Zwerin and Michael H. Kater both report that the inspiration for the band came from the German fighter ace Werner “Vati” Mölders, a keen jazz fan who was reputed to tune in to BBC dance programs as he crossed the Channel to fight in the Battle of Britain. “Hitler had a weak spot for pilots,” Zwerin says, “ when Mölders complained about the unswinging music on German radio, Hitler spoke to Goebbels about it.” True or not, Schwedler’s dance stylings became the come-on for audiences who soon found themselves listening to the heavy-handed propaganda skits that broke up the music. But Joyce and Baillie-Stewart were too smart to miss the chance to mix more messages into the music. With “Charlie’s” help, they began rewriting the standards that the jazzmen played.

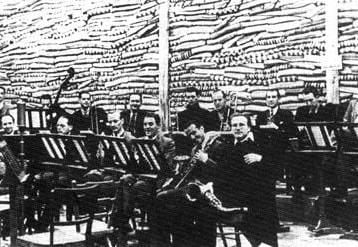

Musically, Schwedler’s orchestra was superior to anything else on offer in Nazi Germany, though scarcely up to the standard of the best American or British bands. It featured Primo Angeli, a virtuoso pianist, and occasional hot drum breaks supplied by Fritz “Freddie” Brocksieper, who was known to have a Greek mother but who hid the fact that he was also one-quarter Jewish. (Brocksieper, for many years the top jazz drummer in Germany, was a devotee of Gene Krupa—to the extent, Michael Kater says, that “he was known for his inordinate noise.”) The band’s ever-growing repertoire consisted mostly of dance standards, mixed with about 15 percent jazz. But it is untrue, Bermeier and Lotz insist, that it featured much “hot” jazz. Such music was regarded as beyond the pale even for propaganda broadcasts, and in any case—as even the American-born propaganda boss Edward Vieth Sittler admitted—“we cannot possibly perform this decadent ‘hot’ jazz as ‘well’ as Negroes and Jews.”

Many of the tracks performed by Charlie and His Orchestra were version of songs from the latest Hollywood movies and Broadway musicals, and despite Schwedler’s efforts in Switzerland it would appear that much of this music came via Nazi listening stations and was roughly transcribed from there. Czech accordionist Kamil Behounek recalled that this practice caused problems. The tracks “were picked up on short or medium wave,” he said, and “a lot of the passages were almost impossible to hear due to atmospherics or fading. So you had to help out with a lot of imagination.”

As the war went on, and more and more Germans were drafted into the armed forces, the composition of “Charlie’s” band changed and it came to include a majority of players from Belgium, France and Italy. The musicians were forced to double up, performing lively propaganda swing arrangements in the mornings and then regrouping in another studio during the afternoons to play Nazi-approved numbers for domestic consumption; by the autumn of 1943, as the bombing of Berlin intensified, they were forced to relocate to Stuttgart and restrict themselves to live broadcasts. “We were on duty five days a week,” bass player Otto “Titte” Tittmann would recall. “We did for the Anglo-American area, plus South America and South Africa.”

Even so, high standards were somehow maintained. Behounek, drafted in as arranger in May 1943, was pleasantly surprised to discover a fully professional setup:

I wondered what sort of village band I was going to be working for. But orders is orders. I got to Berlin in the evening. In the darkness I could make out the ruined buildings which bore witness to the devastating air raids. Next morning I went to the huge broadcasting centre on the Masurenallee…. I felt like Alice in Wonderland. Here was this big dance orchestra with three trumpets, three trombones, four saxes, a full rhythm group. And they were swinging it! And how! They were playing up-to-date hits from America! Lutz Templin had got together the best musicians from all over Europe for his band.

For most of the musicians, Brocksieper admitted after the war, collaboration with the Nazi war machine was simply the lesser of two evils. The alternative was fighting, or in the case of Behounek, working as forced labor in an armaments factory (“My mates were filling shells—I was making music. I don’t see that that is any worse.”) Brocksieper had avoided conscription by swallowing a medicine that induced such severe vomiting that he was diagnosed with a suspected stomach ulcer. Certainly it would have been dangerous for many of the musicians to have shunned the protection offered by Charlie and His Orchestra; the German singer Evelyn Künneke recalled that “there were even half-Jews and gypsies there, Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals and Communists—not exactly the sort of people the Nazis normally wanted to play cards with.”

As “Charlie,” Schwedler—who at least posed as a convinced Nazi—penned lyrics that generally followed a fixed pattern. The first verse of each song would remain untouched, perhaps in the hope of luring in listeners. But the remainder of the lyrics would veer wildly into Nazi propaganda and boasts of Aryan supremacy. Charlie’s main themes were familiar ones: Germany was winning the war and Churchill was a drunken megalomaniac who hid in cellars at night to avoid German bombs (“The Germans are driving me crazy/I thought I had brains/But they shot down my planes”). Similarly, Roosevelt was a puppet of international banking cartels, and the entire Allied war effort was in the service of “the Jews.” For the most part, Schwedler’s songs interspersed virulent anti-Semitism with attempts to convince his audience that Nazi victory was inevitable. When Cole Porter’s classic “You’re the Top” got Charlie’s treatment, the revised lyrics emerged as “You’re the top/You’re a German flyer/You’re the top/You’re machine gun fire/You’re a U-boat chap/With a lot of pep/You’re grand,” and the lyrics for “I’ve Got a Pocketful of Dreams” became “I’m gonna save the world for Wall Street/Gonna fight for Russia, too/I’m fightin’ for democracy/I’m fightin’ for the Jew.”

As for the smash hit “Little Sir Echo,” by the time Schwedler finished with it, it was unrecognisable:

Poor Mr. Churchill, how do you do?

Hello… Hello…

Your famous convoys are not coming through

Hello …

German U boats are making you sore…

You’re nice little fellow, but by now you should know

That you never can win this war.

For the most part, there seems to be little evidence that Charlie and His Orchestra had anything like the impact on Allied morale that Goebbels hoped for. Schwedler might speak perfect English, but he never grasped British and American irony and understatement, and although his band recorded as many as 270 tracks between 1941 and 1943, and their records were distributed to prisoner of war camps, they were generally smashed by the POWs after an exploratory listen.

Yet so important were Charlie and His Orchestra to Goebbels’ propaganda machine that the band was maintained almost to the end of the war. The last of their broadcasts seems to have been made in early April 1945, just a month before the end of the conflict in Europe and a matter of days before the U.S. Army took the Rhineland and Reichssender Stuttgart went off air, blown up by a retreating detachment of the SS.

Not that the orchestra’s main men were out of action for long. Demand for dance music was just as strong under American occupation, and by the autumn of 1945 Lutz Templin was working for the U.S. Army and touring extensively in southern Germany. He later developed his own music publishing business in Hamburg and worked in A&R for Polydor. Fritz Brocksieper spent the last few weeks of the war hiding on a farm near Tübingen. He soon resumed his stalled career as Germany’s top drummer and continued to record until his death in 1990—ironically from a burst stomach ulcer.

As for Karl Schwedler, the chameleon, he proved himself just as adaptable after 1945 as he had during the war. Old acquaintances found him working as a croupier in the casino at the Europa Pavilion in West Berlin; then, in 1960, and despite his unresolved Nazi past, “Charlie” emigrated with his wife and children to the United States. It is not known whether he ever performed there.

Sources

Adam Cathcart. “Music and politics in Hitler’s Germany.” Madison Historical Review 3 (2006); Tim Crook. International Radio Journalism: History, Theory and Practice. London: Routledge, 1998;Brenda Dixon Gottschild. Waltzing in the Dark: African American Vaudeville and Race Politics in the Swing Era. New York: Palgrave, 2000; Roger Hillman. Unsettling Scores: German Film, Music, and Ideology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005; John Bush Jones. The Songs That Fought the War: Popular Music and the Home Front, 1939-1945. Lebanon : Brandeis University Press, 2006; Michael Kater. Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992; Horst Heinz Lange. Jazz in Deutschland: die Deutsche Jazz-Chronik bis 1960. Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1996; Martin Lücke. Jazz im Totalitarismus: Einer Komparative Analyse des Politisch Motivierten Umgangs mit dem Jazz Während des Zeit des Nationalsocialismus und der Stalinismus. Münster: Lit Verlag, 2004; David Snowball. “Controlling degenerate music: jazz in the Third Reich.” In Michael Budds (ed). Jazz and the Germans: Essays on the Influence of “Hot” American Idioms on 20th Century German Music. Maesteg: Pendragon Press, 2002; Michael Zwerin. La Tristesse de Saint Louis: Swing Under the Nazis. London: Quartet, 1988.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)