A Holocaust Survival Tale of Sex and Deceit

One Jewish woman’s personal story reveals what it took to elude capture in Nazi Germany

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/3a/943a1965-cca8-4c75-a023-21b05bcfb05c/image_12_pg_109jpg.jpeg)

In 1942, Marie Jalowicz, a Jewish girl hiding in Berlin, watched as a barkeep sold her for 15 marks to a man mysteriously nicknamed "the rubber director." As Marie recounts in the recently published Underground in Berlin, a riveting chronicle of her story told in her words, she was desperate for a place to sleep. The barkeep pulled Marie aside before she left with the man. Her fabricated backstory was simple; she just couldn't bear to live with her in-laws anymore. But, the barkeep added, her new patron was also "a Nazi whose fanaticism bordered on derangement."

Marie had reasons to be alarmed beyond the man’s avowed Nazism. The "rubber director" earned his nickname from his wobbly gait, and Marie once heard that people in the late stages of syphilis "walked as if their legs were made of rubber, and they could no longer articulate properly." The man walking her to his house was stumbling over his words. And she was to sleep with this man, just to have a place to hide.

They arrived at his apartment, and the man showed off his wall-to-wall collection of aquarium tanks. He recalled the time when he was in a sanatorium and made a matchstick model of Marienburg, dedicating it to the Führer. He showed her an empty picture frame. Marie recalls:

"Any idea what that is?" he asked me, pointing at it.

"No idea at all."

Even if I'd guessed, I would never have said so. Finally, he revealed the secret: he had acquired this item by complicated means and at some expense, as he told me, closing his eyes. It was a hair from the Führer's German shepherd.

They sat together and Marie listened to his Nazi rants, growing increasingly uncomfortable until she changed the subject back to the fish. And then she got extraordinarily lucky: "With bowed head and tears in his eyes, he said he was afraid he must disappoint me: he was no longer capable of any kind of sexual relationship. I tried to react in a neutral, friendly manner, but I was overcome by such relief and jubilation that I couldn't sit still, and fled to the toilet."

Underground in Berlin is filled with similar stories that illustrate the sexual politics of being a young Jewish girl in need of protection during World War II. For 50 years, Marie kept quiet about her experience, but just before her death in 1998, she recorded her memories on 77 cassette tapes. In the 15 years since her death, Marie's son, Hermann, has been transcribing and fact-checking the tapes, and found that his mother remembered with near-perfect clarity the wealth of names and details of her life in Berlin.

For eight years Marie and her family had witnessed Hitler's rise to power: Jews, wearing the legally mandated yellow stars on their coats, were first excluded from many professions and public places, and then many were sent to do forced labor. Marie’s mother, who had been sick with cancer for a long time, died in 1938; her weary, lonely father in early 1941. Before her father’s death, Marie worked with 200 other Jewish women at Siemens, bent over lathes, making tools and weapon parts for the German army. She befriended some of the girls, and they rebelled when they could: singing and dancing in the restroom, sabotaging screw and nut manufacturing. When her father died, she convinced her supervisor to fire her, since Jews weren’t allowed to quit. She lived off the small sum she received from her father’s pension.

In the fall of 1941, about a year before her incident with the “rubber director,” Marie watched her remaining family and friends receive deportation orders to concentration camps for certain death. Her Aunt Grete, one of the first to be sent, begged Marie to come with her. "Sooner or later everyone will have to go," Grete reasoned. With much difficulty, Marie said no. "You can't save yourself. But I am going to do everything imaginable to survive," she told her aunt.

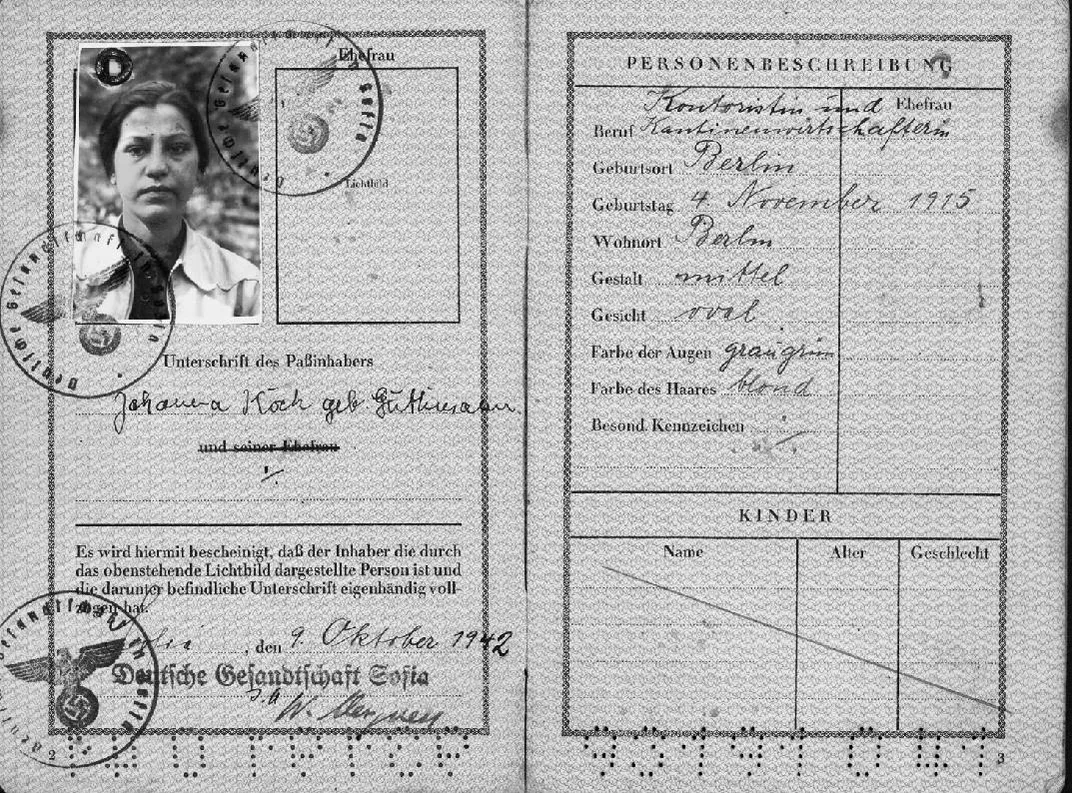

And so she went to great lengths to protect herself. Marie removed her yellow star and assumed the identity of a close friend, Johanna Koch, 17 years older than Marie. Marie doctored Koch’s papers with ink-erasing fluid and forged an approval stamp by hand, exchanged the photo on the ID card, and called herself Aryan. Sometimes, her deception also led her to take lovers and boyfriends as a means of survival.

On the eve of World War II in 1938, Marie and her father were living with friends, the Waldmanns. Marie's father and Frau Waldmann had a fling, and 16-year-old Marie took it upon herself to sleep with Herr Waldmann, to lessen the chance that he would turn Marie and her father out on the street in anger.

Later, hoping to emigrate to Shanghai, she found a Chinese man living in Berlin who agreed to marry her: "Privately I thought: if I can get a Chinese passport through him, that would be excellent, but this isn't a relationship that will come to anything." But even after applying for marriage, and making up a story about being pregnant, she couldn’t get permission from the mayor’s office to marry him.

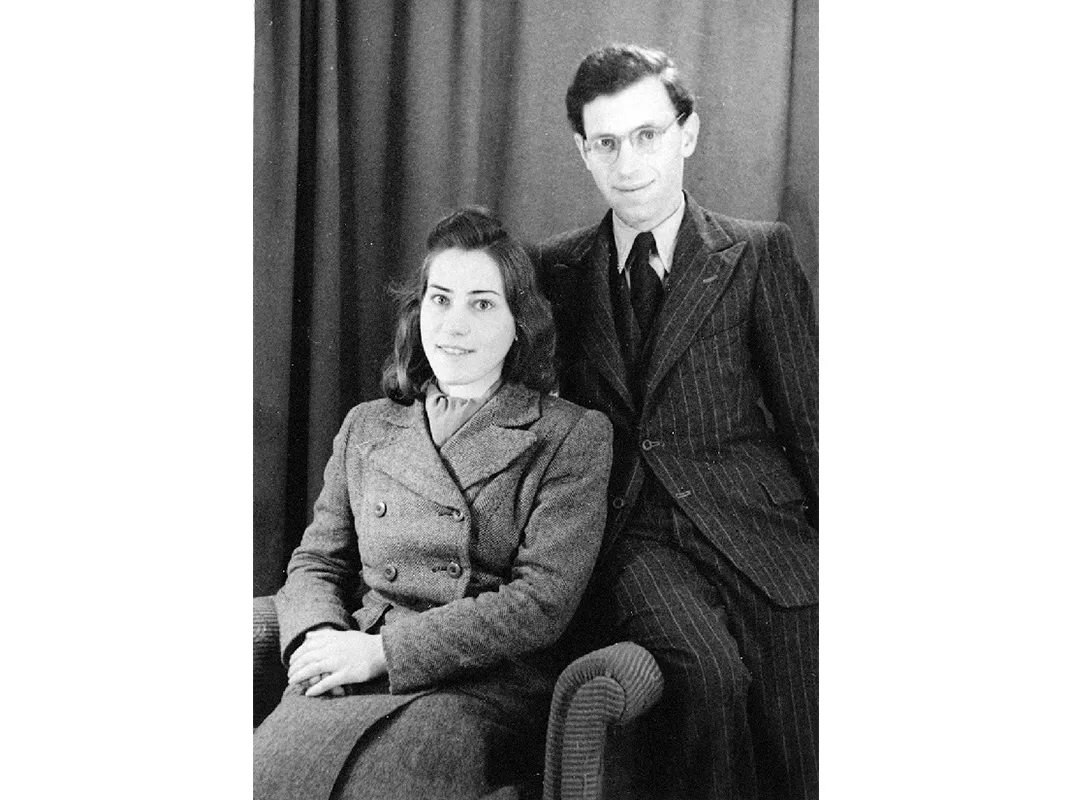

While hiding in the apartment of a friend's cleaning lady, Marie met a Bulgarian named Mitko, a neighbor who came by to paint the place. The two instantly became fond of each other and planned to marry. Marie makes it to Bulgaria with Mitko, and he finds a corrupt lawyer who might be able to make her stay in the country legal.

"You are here with this enchanting lady from Germany?" [the lawyer] asked my lover.

"I could use her as a governess for my little boy! The papers wouldn't cost anything, if you take my meaning?," he winked in a vulgar manner.

Mitko, a naive but decent character, was indignant at this improper suggestion. "We can do without your services," he said brusquely, and he stood up and left.

"As you like," the lawyer called after him. "We'll see what comes of this."

The lawyer turned them in to the Bulgarian police, and Marie was sent back to Berlin alone. Mitko stayed behind with family, weary from weeks of going to great lengths to protect Marie and himself. Upon her return, she was asked to wait for the Gestapo to approve her “unusual passport.” She narrowly escaped the Gestapo by pretending to run after a thief. That night, with nowhere to stay and in need of a bathroom "for the full works," she relieves herself on the doormat of a family with a "Nazi ring" to its name.

Marie's gripping, suspenseful story captures the gloom and anxiety of being alone in wartime Berlin and the struggle to survive on her own. Her will and wit echo the determination and optimism of other accounts of the Holocaust, like those of diarists Viktor Frankl and Anne Frank. But the scenes of sexual commerce and gender politics illuminate an untold reality of surviving as a Jewish woman in the Berlin underground. Marie relays these stories, in which sex is a means of staying alive, a transaction, with evenhandedness, with a sense that it was all worth it.

It's not just bedfellows who help her. Marie finds refuge with non-Jewish friends committed to protecting her, with people her father knew, and with other Jews struggling to live in Berlin. One friend introduces her to Gerritt Burgers, a "crazy Dutchman" who brought Marie to his apartment and tells his landlady, a Nazi supporter named Frau Blase, that

"he had found a woman who was coming to live with him at once. I would keep house for him, and he said I was also ready to lend Frau Blase a hand at any time. Since I was not racially impeccable, it would be better not to register me with the police, he added casually. That didn't seem to both the old woman, but she immediately began haggling over the rent with Burgers."

So begins another situation in which Marie is treated as a good to barter. When the landlord gets mad at Burgers for making a mess, she threatens to call the Gestapo on Marie. When Burgers sees Marie reading, he hits her with his shoe, and tells her, "You're not to read when I'm at home. You're supposed to be here just for me." She's angry, but she sticks it out; she must. They get used to each other.

For as long as Marie lived in the apartment, the supposed wife of a near-stranger, her life is semi-normal, and she benefits from the exchange of her work and pretend love for the company and safety. Frau Blase and Marie share food, and Marie runs errands. Blase shares her life story, talks about her difficult marriage, the death of her son. Marie develops an ambivalent attachment: "I hated Frau Blase as a repellent, criminal blackmailer with Nazi opinions, yet I loved her as a mother figure. Life is complicated."

Hermann, Marie’s son, shares his mother’s post-war story in an afterword. After a long journey of extreme luck, happening upon sympathetic, generous strangers, including a Communist gynecologist and a circus performer, Marie survives the war, poor and with nowhere to go. She went on to teach at the Humboldt University of Berlin and raise a family. She made good on her promise to her aunt Grete, to survive. She knew all along that "other days would come" and she "ought to tell posterity what was happening."