Home Away From Rome

Excavations of villas where Roman emperors escaped the office are giving archaeologists new insights into the imperial way of life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Roman-Villas-Villa-Adriana-631.jpg)

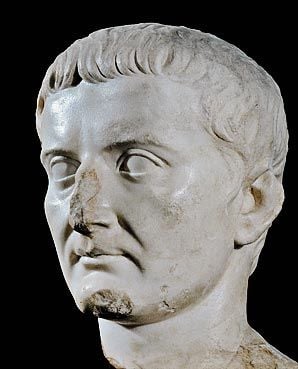

In A.D. 143 or 144, when he was in his early 20s, the future Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius set out for the country estate of his adoptive father, Emperor Antoninus Pius. The property, Villa Magna (Great Estate), boasted hundreds of acres of wheat, grapes and other crops, a grand mansion, baths and temples, as well as rooms for the emperor and his entourage to retreat from the world or curl up with a good book.

Which is just what young Marcus did, as he related in a letter written to his tutor, Fronto, during the excursion. He describes reading Cato’s De agri cultura, which was to the gentlemanly farmer of the Roman Empire what Henry David Thoreau’s Walden was to nature lovers in the 19th century. He hunted boar, without success (“We did hear that boars had been captured but saw nothing ourselves”), and climbed a hill. And since the emperor was also the head of the Roman religion, he helped his father with the daily sacrifices—a ritual that made offerings of bread, milk or a slaughtered animal. The father, son and the emperor’s retinue dined in a chamber adjacent to the pressing room—where grapes were crushed for making wine—and there enjoyed some kind of show, perhaps a dance performed by the peasant farmworkers or slaves as they stomped the grapes.

We know what became of Marcus Aurelius—considered the last of the “Five Good Emperors.” He ruled for nearly two decades from A.D. 161 to his death in A.D. 180, a tenure marked by wars in Asia and what is now Germany. As for the Villa Magna, it faded into neglect. Documents from the Middle Ages and later mention a church “at Villa Magna” lying southeast of Rome near the town of Anagni, in the region of Lazio. There, on privately owned land, remains of Roman walls are partially covered by a 19th-century farmhouse and a long-ruined medieval monastery. Sections of the complex were half-heartedly excavated in the 18th century by the Scottish painter and amateur treasure hunter Gavin Hamilton, who failed to find marble statues or frescoed rooms and decided that the site held little interest.

As a result, archaeologists mostly ignored the site for 200 years. Then, in 2006, archaeologist Elizabeth Fentress—working under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania and the British School at Rome—got permission from the property owner and the Italian government to excavate the area and began to make some interesting discoveries. Most important, near the old farmhouse, her team—accompanied by Sandra Gatti from the Italian Archaeological Superintendency—found a marble-paved rectangular room. At one end was a raised platform, and there were circular indentations in the ground where large terra-cotta pots, or dolia, would have been set in an ancient Roman cella vinaria—a wine pressing room.

The following summer, Fentress and a team discovered a chamber shaped like a semicircular auditorium attached to the pressing room. She was thrilled. Here was the dining area described by Marcus Aurelius where the imperial retinue watched the local workers stomp grapes and, presumably, dance and sing. “If there was any doubt about the villa,” says Fentress, “the discovery of the marble-paved cella vinaria and the banquet room looking into it sealed it.”

In all, roman emperors constructed dozens of villas over the roughly 350-year span of imperial rule,from the rise of Augustus in 27 B.C. to the death of Constantine in A.D. 337. Since treasure hunters first discovered the villas in the 18th century (followed by archaeologists in the 19th and 20th), nearly 30 such properties have been documented in the Italian region of Lazio alone. Some, such as Hadrian’s, at Tivoli, have yielded marble statues, frescoes and ornate architecture, evidence of the luxuries enjoyed by wealthy, powerful men (and their wives and mistresses). As archaeological investigations continue at several sites throughout the Mediterranean, a more nuanced picture of these properties and the men who built them is emerging. “This idea that the villa is just about conspicuous consumption, that’s only the beginning,” says Columbia University archaeologist Marco Maiuro, who works with Fentress at Villa Magna.

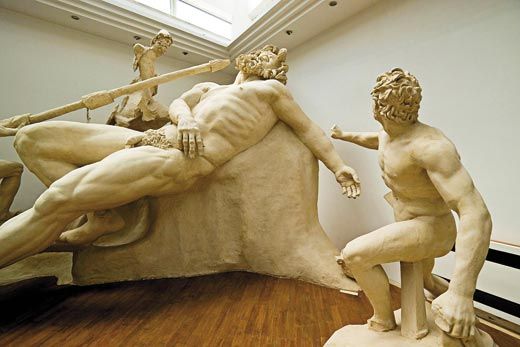

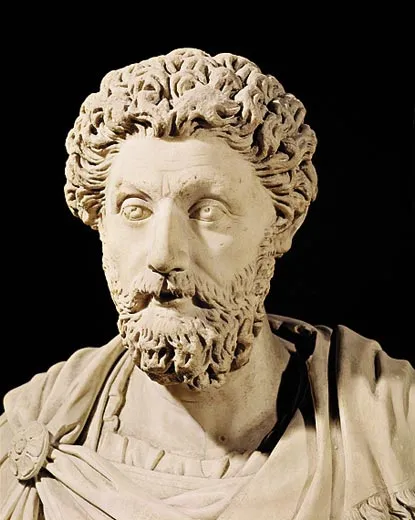

The villas also point up the sharp contrast between the emperors’ official and private lives. “In Rome,” says Steven Tuck, a classical art historian at Miami University of Ohio, “you constantly see them through their service to the state—dedications of buildings, triumphal columns and arches and monuments.” But battles and bureaucracy are left at the villa’s door. Tuck points to his favorite villa—that of Tiberius, Augustus’ stepson, son-in-law and successor. It lies at the end of a sandy beach near Sperlonga, a resort between Rome and Naples on the Mediterranean coast. Wedged between a twisting mountain road and crashing waves, the Villa Tiberio features a natural grotto fashioned into a banquet hall. When archaeologists discovered the grotto in the 1950s, the entrance was filled with thousands of marble fragments. Once the pieces were put together, they yielded some of the greatest sculptural groups ever created—enormous statues depicting the sea monster Scylla and the blinding of the Cyclops Polyphemus. Both are characters from Homer’s Odyssey as retold in Virgil’s Aeneid, itself a celebration of Rome’s mythic founding written just before Tiberius’ reign. Both also vividly illustrate man locked in epic battle with primal forces. “We don’t see this kind of thing in Rome,” says Tuck. It was evocative of a nymphaeum, a dark, primeval place supposedly inhabited by nymphs and beloved by the capricious sea god Neptune. Imagine dining here, with the sound of the sea and torchlight flickering off the fish tail of the monster Scylla as she tossed Odysseus’ shipmates into the ocean.

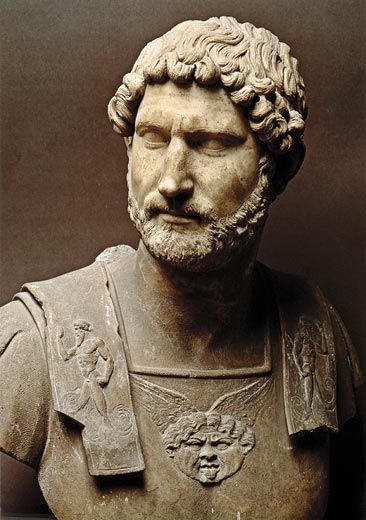

If the imperial villa provided opportunities for Roman emperors to experiment with new images and ideas, then the one that Hadrian (A.D. 76-138) built at Tivoli in the first decades of the second century may be the ultimate in freewheeling expression. Occupying about 250 acres at the base of the Apennine Hills, Villa Adriana was originally a farm. When Hadrian became emperor in A.D. 117, he began renovating the existing structure into something extraordinary. The villa unfolded into a grand interlocking of halls, baths and gathering spaces designed to tantalize and amaze visitors. “This villa has been studied for five centuries, ever since its discovery during the Renaissance,” says Marina De Franceschini, an archaeologist working with the University of Trento. “And yet there’s still a lot to discover.”

Franceschini is especially beguiled by the villa’s outlandish architecture. Take the so-called Maritime Theater, where Hadrian designed a villa within a villa. On an island ringed by a water channel, it is reached by a drawbridge and equipped with two sleeping areas, two bathrooms, a dining room, living room and a thermal bath. The circular design and forced perspective make it appear larger than it is. “The emperor was interested in experimental architecture,” says Franceschini. “It’s an extremely complicated place. Everything is curved. It’s unique.”

What exact statement Hadrian wanted to make with his villa has been the subject of debate since the Renaissance, when the great artists of Italy—including Raphael and Michelangelo—studied it. Perhaps to a greater extent than any other emperor, Hadrian possessed an aesthetic sensibility, which found expression in the many beautiful statues discovered on the site, some of which now grace the halls of the Vatican museums and the National Museum of Rome, as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Louvre in Paris.

Hadrian traveled frequently, and whenever he returned to Italy, Tivoli became his preferred residence, away from the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill. Part business, part pleasure, the villa contains many rooms designed to accommodate large gatherings. One of the most spacious is the canopus—a long structure marked by a reflecting pool said to symbolize a canal Hadrian visited in Alexandria, Egypt, in A.D. 130, where his lover Antinous drowned that same year. Ringing the pool was a colonnade connected by an elaborate architrave (carved marble connecting the top of each column). At the far end is a grotto, similar to that at Sperlonga but completely man-made, which scholars have named the Temple of Serapis, after a temple originally found at Alexandria.

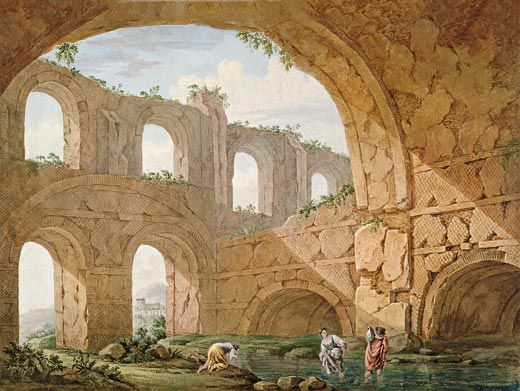

Today, the canopus and grotto may look austere, but with the emperor seated there with up to 100 other diners around the pool, it must have been something to see. A network of underground tunnels some three miles long trace a labyrinth beneath the villa, which allowed servants to appear, almost magically, to refill a glass or serve a plate of food. The pool on a warm summer night, reflecting the curvilinear architrave, was surely enchanting.

Standing at the grotto today, one can barely see the line made by two small aqueducts running from a hillside behind the grotto to the top of this half-domed pavilion. Water would have entered a series of pipes at its height, run down into walls and eventually exploded from niches into a semi-circular pool and passed under the emperor. Franceschini believes the water was mostly decorative. “It reflected the buildings,” he says. “It also ran through fountains and grand waterworks. It was conceived to amaze the visitor. If you came to a banquet in the canopus and saw the water coming, that would have been really spectacular.”

Hadrian was not the only emperor to prefer country life to Rome’s imperial palace. Several generations earlier, Tiberius had retired to villas constructed by his predecessor Augustus. Installing a regent in Rome, the gloomy and reclusive Tiberius walled himself off from the world at the Villa Jovis, which still stands on the island of Capri, near Neapolis (today’s Naples hills). Tiberius’ retreat from Rome bred rumor and suspicion. The historian Suetonius, in his epic work The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, would later accuse him of setting up a licentious colony where sadomasochism, pederasty and cruelty were practiced. (Most historians believe these accusations to be false.) “Tradition still associates the great villas of Capri with this negative image,” says Eduardo Federico, a historian at the University of Naples who grew up on the island. Excavated largely in the 1930s and boasting some of the most spectacular vistas of the Mediterranean Sea of any Roman estate, the Villa Jovis remains a popular tourist destination. “The legend of Tiberius as a tyrant still prevails,” says Federico. “Hostile history has made the Villa Jovis a place of cruelty and Tiberian lust.”

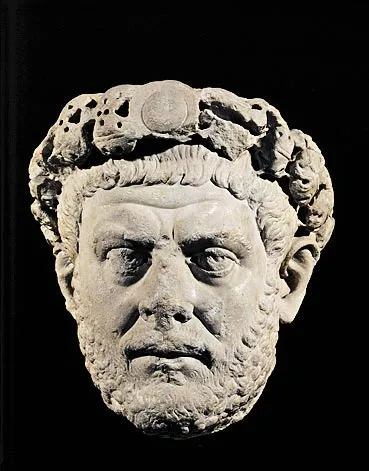

Perhaps the best-known retirement villa belonged to the emperor Diocletian (A.D. 245-316), who ruled at the end of the third century and into the fourth. Besides his tireless persecution of Christians, Diocletian is known for ending a half-century of instability and consolidating the empire—before dividing it into eastern and western halves (thereby setting the stage for the rise of the Byzantine Empire). Much of this work involved quelling rebellions on the perimeter and keeping the ever-agitating senatorial class under control. By A.D. 305, at the age of 60, Diocletian had had enough. In a bold, unprecedented move—previous emperors had all died in office—he announced his retirement and sought refuge in a seaside villa on the coast of Dalmatia (today’s Croatia).

Now called Diocletian’s Palace, the ten-acre complex includes a mausoleum, temples, a residential suite and a magnificent peristyle courtyard complete with a dais and throne. Even out of power, Diocletian remained a force in the empire, and when it fell into chaos in 309, various factions pleaded for him to take up rule again. Diocletian demurred, famously writing that if they could see the incredible cabbages he’d grown with his own hands, they wouldn’t ask him to trade the peace and happiness of his palace for the “storms of a never-satisfied greed,” as one historian put it. He died there seven years later.

Located in the modern city of Split, Diocletian’s Palace is one of the most stunning ancient sites in the world. Most of its walls still stand; and although the villa has been looted for treasure, a surprising number of statues—mostly Egyptian, pillaged during a successful military campaign—still stand. The villa owes its excellent condition to local inhabitants, who moved into the sprawling residence not long after the fall of Rome and whose descendants live there to this day. “Everything is interwoven in Split,” says Josko Belamaric, an art historian with the Croatian Ministry of Culture who is responsible for conservation of the palace. “It’s so dense. You open a cupboard in someone’s apartment, and you’re looking at a 1,700-year-old wall.”

Belamaric has been measuring and studying Diocletian’s Palace for more than a decade, aiming to strike a balance between its 2,000 residents and the needs of preservation. (Wiring high-speed Internet into an ancient villa, for instance, is not done with a staple gun.) Belamaric’s studies of the structure have yielded some surprises. Working with local architect Goran Niksic, the art historian realized that the aqueduct to the villa was large enough to supply water to 173,000 people (too big for a residence, but about right for a factory). The local water contains natural sulfur, which can be used to fix dyes. Belamaric concluded that Diocletian’s estate included some sort of manufacturing center—probably for textiles, as the surrounding hills were filled with sheep and the region was known for its fabrics.

It’s long been thought that Diocletian built his villa here because of the accommodating harbor and beautiful seascape, not to mention his own humble roots in the region. But Belamaric speculates it was also an existing textile plant that drew the emperor here, “and it probably continued during his residence, generating valuable income.”

In fact, most imperial Roman villas were likely working farms or factories beneficial to the economy of the empire. “The Roman world was an agriculturally based one,” says Fentress. “During the late republic we begin to see small farms replaced by larger villas.” Although fish and grains were important, the predominant crop was grapes, and the main product wine. By the first century B.C., wealthy landowners—the emperors among them—were bottling huge amounts of wine and shipping it throughout the Roman Empire. One of the first global export commodities was born.

At Tiberius’ villa at Sperlonga, a series of rectangular pools, fed by the ocean nearby, lay in front of the grotto. At first they seem merely decorative. But upon closer inspection, one notices a series of terra-cotta-lined holes, each about six inches in diameter, set into the sides of the pools, just beneath the water’s surface. Their likely use? To provide a safe space in which fish could lay their eggs. The villa operated as a fish farm, producing enough fish, Tuck estimates, not only to feed the villa and its guests but also to supply markets in Rome. “It’s fantastic to see this dining space that also doubled as a fish farm,” says Tuck. “It emphasizes the practical workings of these places.”

Maiuro believes that the economic power of the larger villas, which tended to expand as Rome grew more politically unstable, may even have contributed to the empire’s decline, by sucking economic—and eventually political—power away from Rome and concentrating it in the hands of wealthy landowners, precursors of the feudal lords who would dominate the medieval period. “Rome was never very well centralized,” says Maiuro, “and as the villas grow, Rome fades.”

Paul Bennett lived in Italy for five years and has lectured widely on Roman history, archaeology and landscape design.