Horse-Riding Librarians Were the Great Depression’s Bookmobiles

During the Great Depression, a New Deal program brought books to Kentuckians living in remote areas

Their horses splashed through iced-over creeks. Librarians rode up into the Kentucky mountains, their saddlebags stuffed with books, doling out reading material to isolated rural people. The Great Depression had plunged the nation into poverty, and Kentucky—a poor state made even poorer by a paralyzed national economy—was among the hardest hit.

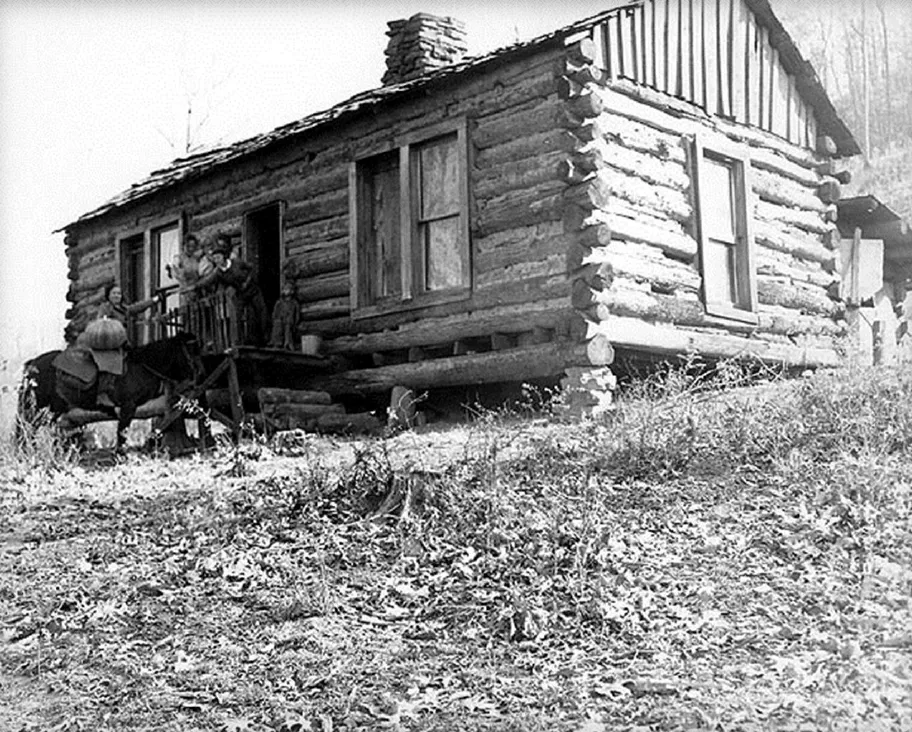

The Pack Horse Library initiative, which sent librarians deep into Appalachia, was one of the New Deal’s most unique plans. The project, as implemented by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), distributed reading material to the people who lived in the craggy, 10,000-square-mile portion of eastern Kentucky. The state already trailed its neighbors in electricity and highways. And during the Depression, food, education and economic opportunity were even scarcer for Appalachians.

They also lacked books: In 1930, up to 31 percent of people in eastern Kentucky couldn’t read. Residents wanted to learn, notes historian Donald C. Boyd. Coal and railroads, poised to industrialize eastern Kentucky, loomed large in the minds of many Appalachians who were ready to take part in the hoped prosperity that would bring. "Workers viewed the sudden economic changes as a threat to their survival and literacy as a means of escape from a vicious economic trap," writes Boyd.

This presented a challenge: In 1935, Kentucky only circulated one book per capita compared to the American Library Association standard of five to ten, writes historian Jeanne Cannella Schmitzer,. It was "a distressing picture of library conditions and needs in Kentucky," wrote Lena Nofcier, who chaired library services for the Kentucky Congress of Parents and Teachers at the time.

There had been previous attempts to get books into the remote region. In 1913, a Kentuckian named May Stafford solicited money to take books to rural people on horseback, but her project only lasted one year. Local Berea College sent a horse-drawn book wagon into the mountains in the late teens and early 1920s. But that program had long since ended by 1934, when the first WPA-sponsored packhorse library was formed in Leslie County.

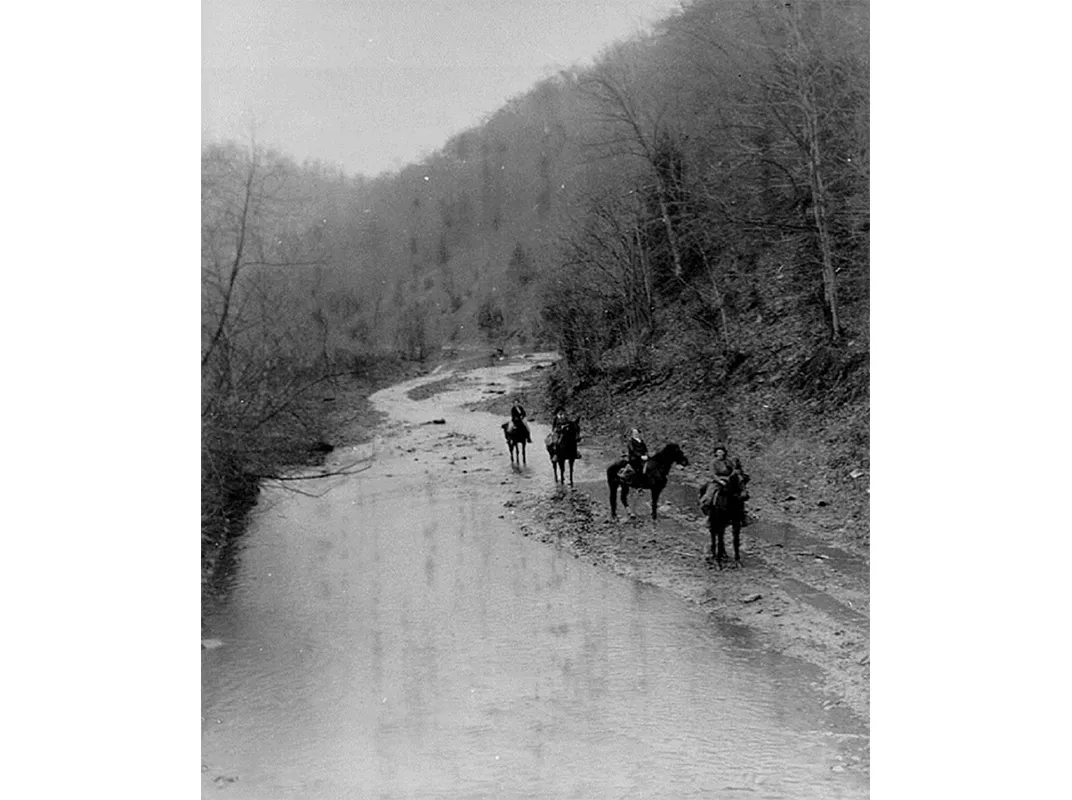

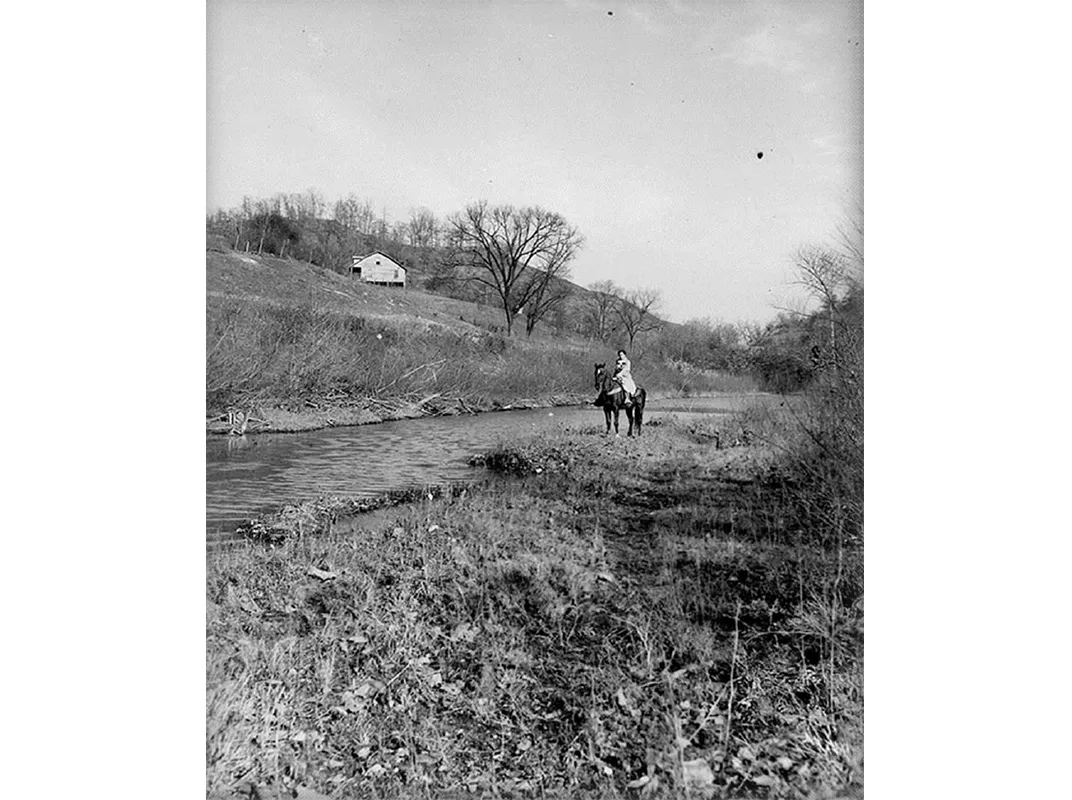

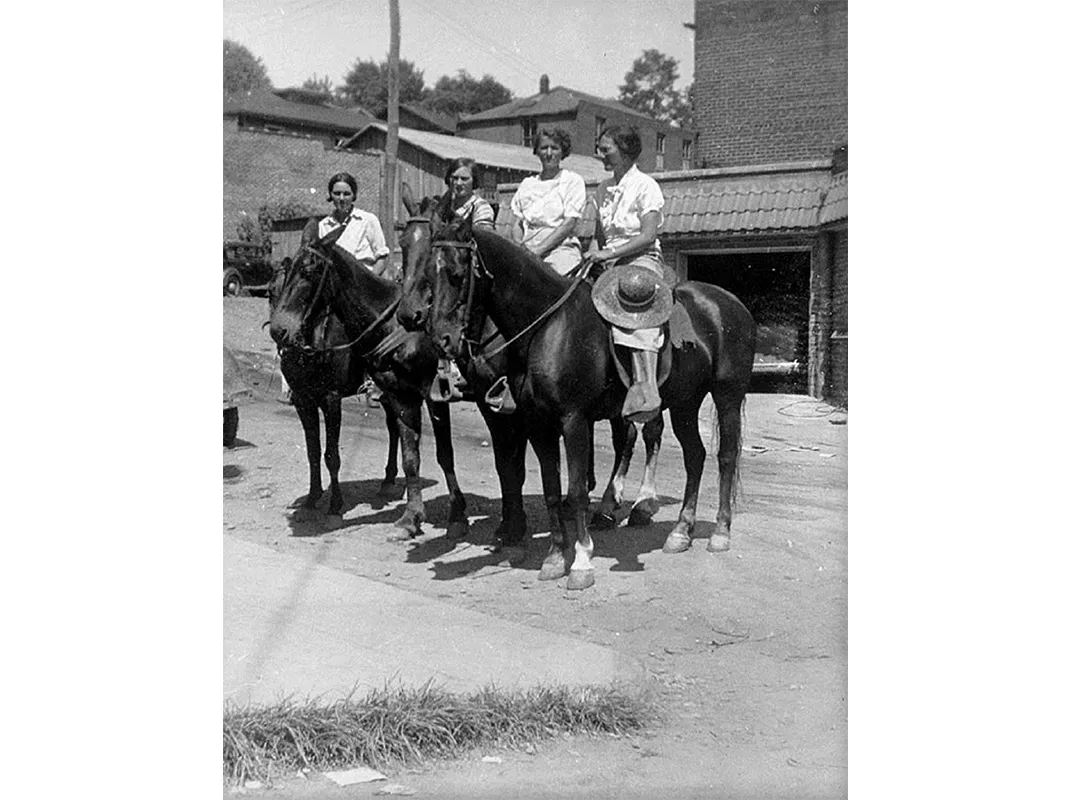

Unlike many New Deal projects, the packhorse plan required help from locals. "Libraries" were housed any in facility that would step up, from churches to post offices. Librarians manned these outposts, giving books to carriers who then climbed aboard their mules or horses, panniers loaded with books, and headed into the hills. They took their job as seriously as mail carriers and crossed streams in wintry conditions, feet frozen in the stirrups.

Carriers rode out at least twice a month, with each route covering 100 to 120 miles a week. Nan Milan, who carried books in an eight-mile radius from the Pine Mountain Settlement School, a boarding school for mountain children, joked that the horses she rode had shorter legs on one side than the other so that they wouldn't slide off of the steep mountain paths. Riders used their own horses or mules-—the Pine Mountain group had a horse named Sunny Jim—or leased them from neighbors. They earned $28 a month—around $495 in modern dollars.

The books and magazines they carried usually came from outside donations. Nofcier requested them through the local parent-teacher association. She traveled around the state, asking people in more affluent and accessible regions to help their fellow Kentuckians in Appalachia. She asked for everything: books, magazines, Sunday school materials, textbooks. Once the precious books were in a library’s collection, librarians did everything they could to preserve them. They repaired books, repurposing old Christmas cards as bookmarks so people would be less likely to dog-ear pages.

Soon, word of the campaign spread, and books came from half of the states in the country. A Kentuckian who had moved to California sent 500 books as a memorial to his mother. One Pittsburgh benefactor collected reading material and told a reporter stories she'd heard from packhorse librarians. "Let the book lady leave us something to read on Sundays and at night when we get through hoeing the corn," one child asked, she said. Others sacrificed to help the project, saving pennies for a drive to replenish book stocks and buy four miniature hand-cranked movie machines.

When materials became too worn to circulate, librarians made them into new books. They pasted stories and pictures from the worn books into binders, turning them into new reading material. Recipes, also pasted into binders and circulated throughout the mountains, proved so popular that Kentuckians started scrapbooks of quilt patterns, too.

In 1936, packhorse librarians served 50,000 families, and, by 1937, 155 public schools. Children loved the program; many mountain schools didn't have libraries, and since they were so far from public libraries, most students had never checked out a book. "'Bring me a book to read,' is the cry of every child as he runs to meet the librarian with whom he has become acquainted," wrote one Pack Horse Library supervisor. "Not a certain book, but any kind of book. The child has read none of them."

"The mountain people loved Mark Twain," says Kathi Appelt, who co-wrote a middle-grade book about the librarians with Schmitzer, in a 2002 radio interview. "One of the most popular books…was Robinson Crusoe.” Since so many adults could not read, she noted, illustrated books were among the most beloved. Illiterate adults relied on their literate children to help decipher them.

Ethel Perryman supervised women's and professional projects at London, Kentucky during the WPA years. "Some of the folks who want books live back in the mountains, and they use the creek beds for travel as there are no roads to their places, " she wrote to the president of Kentucky's PTA. “They carry books to isolated rural schools and community centers, picking up and replenishing book stocks as they go so that the entire number of books circulate through the county "

The system had some challenges, Schmitzer writes: Roads could be impassable, and one librarian had to hike her 18-mile route when her mule died. Some mountain families initially resisted the librarians, suspicious of outsiders riding in with unknown materials. In a bid to earn their trust, carriers would read Bible passages aloud. Many had only heard them through oral tradition, and the idea that the packhorse librarians could offer access to the Bible cast a positive light on their other materials. (Boyd’s research is also integral to understanding these challenges)

"Down Hell-for-Sartin Creek they start to deliver readin' books to fifty-seven communities," read one 1935 newspaper caption underneath a picture of riders. "The intelligence of the Kentucky mountaineer is keen," wrote a contemporary reporter. "All that has ever been said about him to the contrary notwithstanding, he is honest, truthful, and God-fearing, but bred to peculiar beliefs which are the basis of one of the most fascinating chapters in American Folklore. He grasped and clung to the Pack Horse Library idea with all the tenacity of one starved for learning."

The Pack Horse Library ended in 1943 after Franklin Roosevelt ordered the end of the WPA. The new war effort was putting people back to work, so WPA projects—including the Pack Horse Library—tapered off. That marked the end of horse-delivered books in Kentucky, but by 1946, motorized bookmobiles were on the move. Once again, books rode into the mountains, and, according to the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Kentucky’s public libraries had 75 bookmobiles in 2014—the largest number in the nation.