How the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty Changed the Plains Indian Tribes Forever

The peace agreement set up reservations for the tribe—only to break that agreement in the following decades

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/b9/e4b9c741-3d70-49d8-9759-a5a5d1ce2215/medicine_lodge_treaty.jpg)

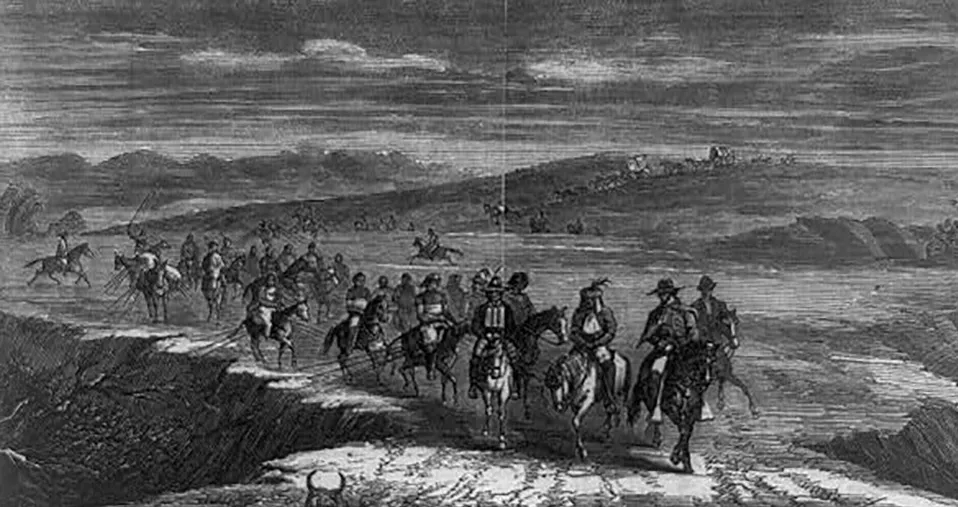

It was an astonishing spectacle: 165 wagons, 600 men, and 1,200 horses and mules, all stretched across the plains of the Kansas territory in October 1867. Their purpose? To escort a cohort of seven men, appointed by Congress to put an end to the bloodshed between the U.S. military and the Indian tribes of the Great Plains, to the sacred site of Medicine Lodge Creek.

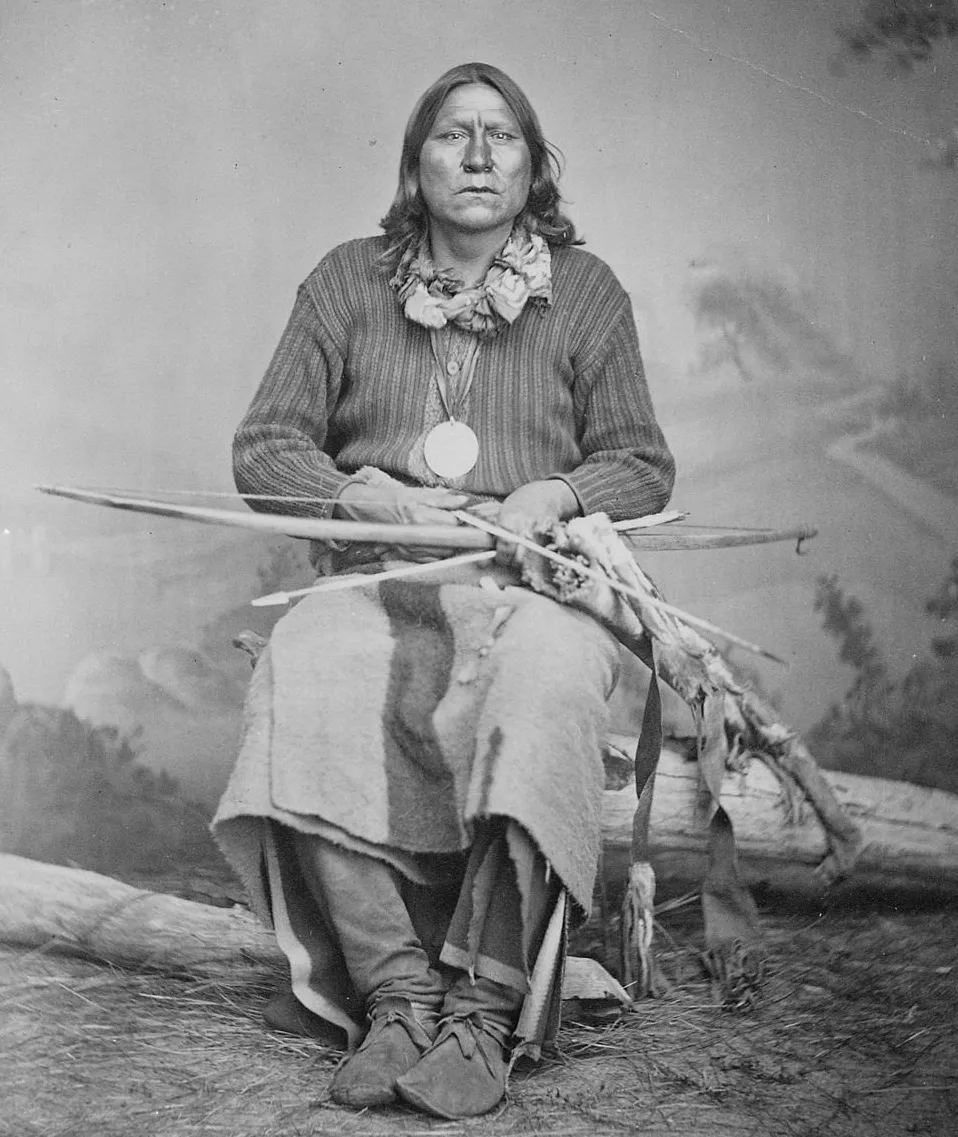

Situated deep into the tribes’ hunting grounds, the meeting spot would host one of the Plains’ Indians most devastating treaties—in large part because it wouldn’t be long before the treaty was broken. The government delegates were met by more than 5,000 representatives of the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho and Kiowa-Apache nations. Two weeks later, members of the Southern Cheyenne joined them as well.

A mere two years had passed since the end of the Civil War, and Americans were still reeling from the bloodshed and social upheaval. As more and more settlers moved westward in hopes of starting anew, and workers assembled the transcontinental railroad, conflicts between Native Americans and the United States erupted in pockets of violence. In 1863, military expeditions attacked a Yanktonai encampment at Whitestone Hill, killing at least 300 men, women and children; in 1864, cavalrymen attacked a group of Cheyenne and Arapaho in Sand Creek, Colorado, killing more than 150 women and children and mutilating their bodies; and just a few months earlier in 1867, Major General Winfield Hancock burned down the Cheyenne-Oglala village of Pawnee Fork in Kansas.

The tribes had attacked U.S. settlements as well, but a series of contemporary government investigations into those incidents blamed “unrestrained settlers, miners, and army personnel as the chief instigators of Indian hostility,” writes historian Jill St. Germain in Indian Treaty-Making Policy in the United States and Canada.

Given the antagonism between the groups, why would Native Americans bother attending such a gathering? For Eric Anderson, a professor of indigenous studies at Haskell Indian Nations University, it’s all about trying to take advantage of the gifts offered by the U.S. government, and hoping to end the costly wars. "They want food rations, they want the arms and ammunition, they want the things being offered to them," Anderson says. "They want some assurances of what's in the future for them. New people are coming in and essentially squatting on tribal land, and the cost of war for them is incredibly high."

For the Americans, ending the wars and moving towards a policy of “civilizing” Native Americans were equally important reasons to initiate the gathering. “When the U.S. sends a peace commission out there, it’s a recognition that its military policy against the tribes isn’t working,” says Colin Calloway, professor of history at Dartmouth and author of Pen and Ink Witchcraft: Treaties and Treaty Making in American Indian History. “[The commissioners were] people of good intentions, but it’s clear where the U.S. is going. Indians have to be confined to make way for railroads and American expansion.”

But how to achieve this result wasn’t at all clear by the time of the Medicine Lodge Peace Commission. Although the bill to form a peace commission quickly gained approval in both houses of Congress in July 1867, the politicians appointed a combination of civilians and military personnel to lead the treaty process. The four civilians and three military men (including Civil War General William T. Sherman) reflected Congress’s uncertainty in whether to proceed with diplomacy or military force. In the months preceding the peace commission, Sherman wrote, “If fifty Indians are allowed to remain between the Arkansas and the Platte [Rivers] we will have to guard every stage station, ever train, and all railroad working parties… fifty hostile Indians will checkmate three thousand soldiers.”

Sherman’s concern about nomadic Indians was echoed in Congress, where members claimed it cost upwards of $1 million a week to fund the militias defending frontier populations. A peace treaty seemed like a much less costly alternative, especially if the tribes agreed to live on reservations. But if peace failed, the bill stipulated that the secretary of war would take up to 4,000 civilian volunteers to remove the Indians by force, writes historian Kerry Oman.

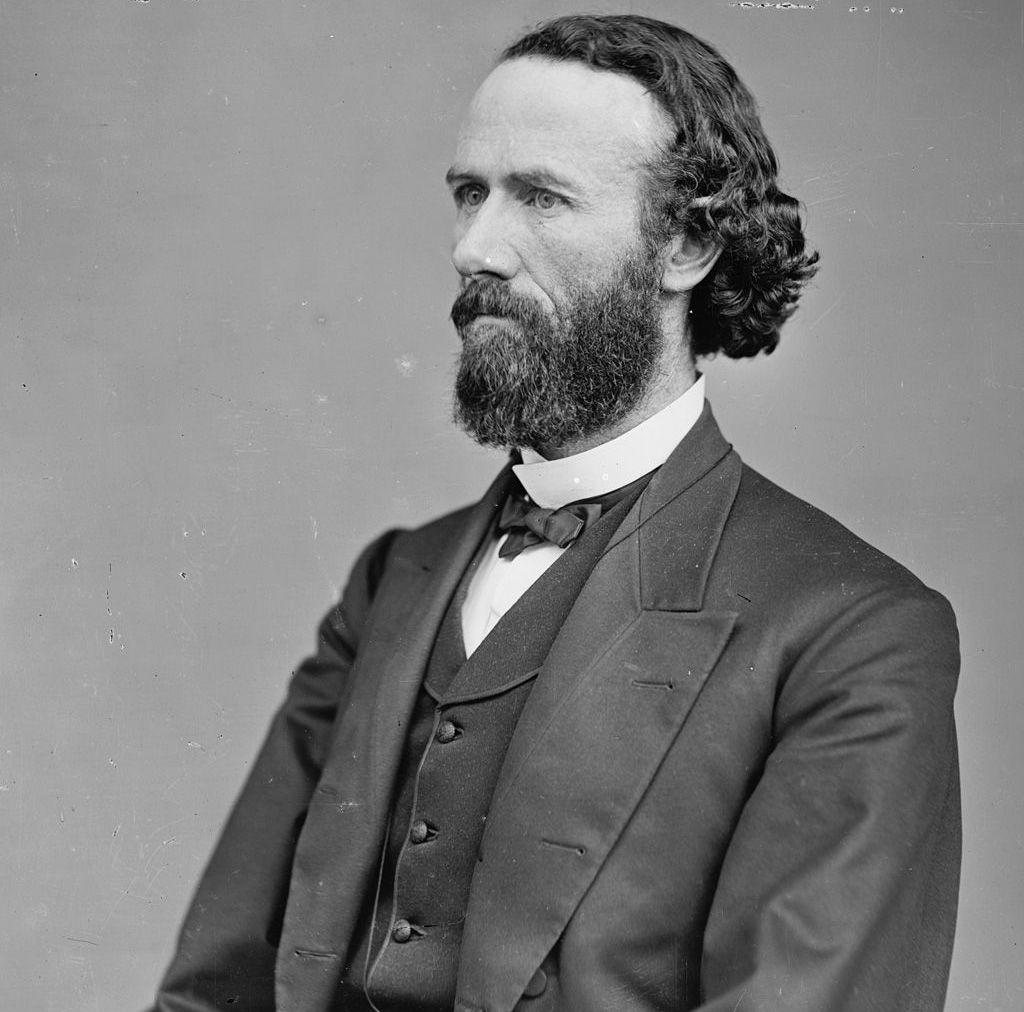

Meanwhile at Medicine Lodge, the government representatives led by Senator John Henderson of Missouri (the chair for the Senate Committee of Indian Affairs) began negotiating the terms of a potential treaty with members of the different nations. Between the crowds of people, the multiple interpreters needed, and the journalists roving around the camp, it was a chaotic process. The treaty offered a 2.9-million-acre tract to the Comanches and Kiowas and a 4.3-million-acre tract for a Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation. Both of these settlements would include the implements for farming and building houses and schools, and the land would be guaranteed as native territory. The tribes were also given permission to continue hunting buffalo populations for as long as they existed—which wasn’t destined to be long, as activities that led to their near-complete extermination were already underway.

The proposal put forward by Henderson—for the tribes to transition from nomadism to a sedentary life of farming—wasn’t received with much enthusiasm.

“This building of homes for us is all nonsense. We don’t want you to build any for us. We would all die. My country is small enough already. If you build us houses, the land will be smaller. Why do you insist on this?” Chief Satanta of the Kiowas responded.

The sentiment was echoed by council chief Buffalo Chip of the Cheyenne, who said, “You think you are doing a great deal for us by giving these presents to us, but if you gave us all the goods you could give, yet we would prefer our own life. You give us presents and then take our lands; that produces war. I have said all.”

Yet for all their resistance to the changes, tribe members signed the treaty on October 21 and then on October 28. They took the proffered gifts the American negotiators brought with them—beads, buttons, iron pans, knives, bolts of cloth, clothes and pistols and ammunition—and departed for their territories. Why the tribes acquiesced is something historians are still trying to puzzle out.

“[One provision of the agreement] says the Indians don’t have to give up any more land unless three-fourths of the adult male population agree to do so,” Calloway says. “That must’ve seemed like an iron-clad guarantee, a sign that this was a one-time arrangement. And of course we know that wasn’t the case.”

It’s also possible the tribes weren’t planning on following the agreement to the letter of the law, Anderson suggests. They brought their own savvy to the negotiating tables, fully aware of how malleable treaties with the American government tended to be.

There’s also the unavoidable problem of what might have been lost in translation, both linguistically and culturally. For Carolyn Gilman, a senior exhibit developer at the National Museum of the American Indian, representatives of the United States never seemed to understand the political structure of tribes they negotiated with.

“They ascribed to Indian tribes a system of power that in fact did not exist,” Gilman says. “The chiefs are looked on as mediators and councilors, people who may represent the tribe to outside entities but who never have the authority to give orders or compel the obedience of other members.”

In other words, chiefs from different nations may have affixed their mark to the treaty document, but that doesn’t mean the members of their nations felt any obligation to abide by the treaty. And even if they planned on following the treaty, their interpretation of its stipulations was likely quite different than what the U.S. government intended.

“By the early 20th century, life on reservations was similar to life in the homelands of apartheid South Africa—people had no freedom of movement, they had no freedom of religion. Basically all their rights were taken away,” Gilman says. “But in 1867, nobody knew that was going to happen.”

In the end, the tribes’ reasons for signing the treaty didn’t make much difference. Although the document was ratified by Congress in 1868, it was never ratified by adult males of the participating tribes—and it wasn’t long before Congress was looking for ways to break the treaty. Within a year, treaty payments were withheld and General Sherman was working to prevent all Indian hunting rights.

In the following years, lawmakers decided the reservations were too large and needed to be cut down to individual plots called “allotments.” These continual attempts to renege on the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty came to a head in 1903 in the landmark Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock case, in which a member of the Kiowa nation filed charges against the Secretary of the Interior. The Supreme Court ruled that Congress had the right to break or rewrite treaties between the United States and Native American tribes however the lawmakers saw fit, essentially stripping the treaties of their power.

“The primary importance of the Medicine Lodge Treaty in American Indian history is related to the spectacular and unethical way that the treaty was violated,” Gilman says. “The decision in Lone Wolf v. Hancock was the American Indian equivalent of the Dred Scott decision [which stated that African-Americans, free or enslaved, could not be U.S. citizens].”

For Anderson, the Medicine Lodge Treaty also marked a shift away from genocide to policies that we would today term “ethnocide”—the extermination of a people’s culture. It ushered in the years of mandatory boarding schools, language suppression and bans on religious practices. But for Anderson, Gilman and Calloway alike, what’s most impressive about this broken treaty and others like it is the resiliency of the American Indians who lived through those policies.

According to Calloway, that’s one reason for optimism in light of so much violence. “The Indians manage to survive, and they manage to survive as Indians.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)