How a 1897 Massacre of Pennsylvania Coal Miners Morphed From a Galvanizing Crisis to Forgotten History

The death of 19 immigrants may have unified the labor movement, but powerful interests left their fates unrecognized until decades later

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/4b/1f4bbfc1-54e9-456a-87a2-8b7c0df45ca9/lattimer_massacreuse_this_one.jpg)

At the western entrance of the coal patch town of Lattimer, in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, sits a rough-cut shale boulder, about eight feet tall, surrounded by neatly trimmed bushes. A bronze pickax and a shovel are attached to the boulder, smaller pieces of coal rest at its base, and an American flag flies high above it.

Locals and union members sometimes refer to the boulder as the “Rock of Remembrance” or the “Rock of Solidarity.” Still others call it the Lattimer Massacre Memorial. It was erected to memorialize immigrant coal miners from Eastern Europe who were killed by local authorities in 1897 when they protested for equal pay and better working conditions. The boulder is adorned with a bronze plaque that describes the massacre and lists the names of the men who died at the site.

What’s most interesting about the memorial is that it was built in 1972. Why did it take 75 years to commemorate the 19 men killed at Lattimer? I’ve devoted close to a decade to understanding how the event is remembered and why it took so long to pay permanent tribute.

Maybe the memory of Lattimer was repressed because, as The Hazleton Sentinel noted a day after the massacre, “The fact that the victims are exclusively foreigners has detracted, perhaps from the general expression.” The massacre occurred in an era when established American citizens were afraid of the nation losing its white, Anglo-Saxon identity amidst an influx of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. The newer arrivals were seen as inferior, with strange customs and different languages.

Perhaps a sense of historical amnesia surrounded Lattimer because it is located in a relatively rural location, away from major cities and newspapers. Or perhaps it was beneficial for the coal barons and other economic leaders in Pennsylvania to forget the demands of their workers. But whatever the reason, remembering what happened at Lattimer is essential today. The massacre offers a double reminder—of both the long struggle of unions to gain fair wages and safe working conditions, and the travails faced by immigrants to the United States in the past and present.

The story of the Lattimer massacre began a decade before the actual event, in the 1880s. At that time, many eastern and southern Europeans migrated to northeastern Pennsylvania to work in the anthracite coal mines, which exported large quantities of coal to East Coast cities like Philadelphia and New York to heat homes and fuel industry.

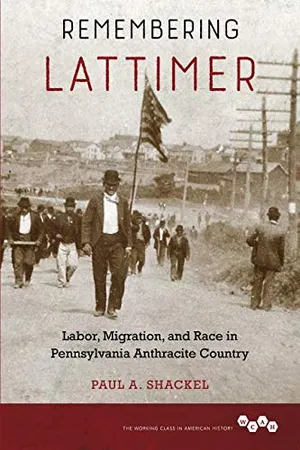

Remembering Lattimer: Labor, Migration, and Race in Pennsylvania Anthracite Country (Working Class in American History)

Beginning with a dramatic retelling of the incident, Shackel traces how the violence, and the acquittal of the deputies who perpetrated it, spurred membership in the United Mine Workers. By blending archival and archaeological research with interviews, he weighs how the people living in the region remember--and forget--what happened.

These new arrivals reflected changes in mining. The coal industry of the early 19th century had attracted miners from England, Scotland and Wales. By the 1840s, the Irish had become the new laboring class in the region. As mines became deeper over the century, the work within them became less safe. By the time the eastern and southern European immigrants arrived, coal operators tended to recruit more workers than they needed, creating a pool of able men who could step in at little notice to replace workers who were injured, dead or on strike. Ample surplus labor allowed coal operators to keep wages at near-starvation levels.

The United Mine Workers of America, a union established in 1890, wasn’t much help to the new immigrant miners—it was concerned primarily with protecting the jobs of the native or naturalized coal workers, the “English speakers.” It backed the 1897 Campbell Act, which levied a 3-cent-a-day state tax on coal operators for each non-U.S. citizen working in their collieries.

The Campbell Act was officially enacted on August 21, 1897 and the coal operators quickly passed along the tax to the non-naturalized coal miners. This was the latest in a series of insults. Some immigrant miners were already being paid 10 to 15 percent less than the “English speakers” in some jobs. Many had recently gone on strike after a mining superintendent had beaten a young mule driver over the head with a hand ax in the name of “work discipline.” When some saw a new deduction in their compensation, they decided they had had enough.

Miners hoped to close all of the mines in the area with their strike, but coal operations in Lattimer continued. So, on the morning of Sunday, September 10, 1897, a group of miners gathered for a rally in the coal patch town of Harwood to protest the ongoing operations. Carrying an American flag, the men, mostly from Eastern Europe, began a peaceful march to Lattimer in the early afternoon. Luzerne County sheriff James Martin and his deputies harassed the 400 or so men as they walked.

At 3:45 p.m., at the outskirts of Lattimer, a confrontation ensued. Eighty-six deputies, joined by coal company police, lined the sides of the road; perhaps 150 of the men were armed with rifles and pistols. Martin ordered the miners to abandon their march. Some miners pushed forward, someone yelled “Fire!” and several men immediately fell dead in their tracks. The rest of the miners turned and began to run away, but the firing continued for about two minutes, and over a dozen protesters were shot in the back while fleeing. Nineteen men died that day, and as many as five more died from gunshot wounds later that week.

Almost immediately, the 19 immigrant men who fell at Lattimer were transformed into martyrs, symbols of the labor struggle in the anthracite region.

And just as quickly, retellings of the event launched a long struggle to control the memory and meaning of Lattimer. The slain strikers were buried in four different Hazleton cemeteries with great ceremony, most in paupers’ graves. As many as 8,000 people participated in the funeral ceremonies and processions. A Polish newspaper, which was published in Scranton, memorialized the men with a rephrasing of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. For those who died in Lattimer, it wrote, “May their death not be in vain, may they become the patron saints of the working people in America.”

Martin and his deputies were tried in February 1898 for killing one striker, but were found innocent after defense attorneys characterized the miners as “invaders from the Steppes of Hungary” who had come to America to destroy peace and liberty. An alternative narrative took shape, built on the sorts of prejudices Martin’s defense team had so successfully employed. The Century Magazine, a famous national publication, published a series of articles that described the miners in a racist, condescending tone, recounting “the scene of the attack on the deputies.” Powerful interests took heed. Miners who had been involved in the strike, as well as supervisors and other miners who publicly supported the strikers, lost their jobs. Those who continued working still suffered under harsh conditions.

The backlash against immigrant miners took hold to such a degree, that just two years later, UMWA president John Mitchell called for a strike and added a plea for a more inclusive union. “The coal you dig isn’t Slavish or Polish, or Irish coal. It’s just coal,” he exclaimed. The phrase became the rallying slogan for the 1900 strike as well as the famous 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike, which won better working conditions, a shorter workday and wage hikes. With increasing support from foreign-born workers, the UMWA began to recognize Lattimer as an event that cemented new immigrant labor’s loyalty to the union.

But the pendulum would swing back and forth when it came to celebrating the strikers. One month after Sheriff Martin’s trial, a local newspaper wrote about a movement to establish a memorial to the victims. On the first anniversary of the massacre, 1,500 to 2,000 miners paraded through Hazleton in remembrance of their labor martyrs. In 1903, union locals collected over $5,000 to erect a monument to the miners killed at Lattimer—but for the next decade people argued about where the memorial should be located. Lattimer was still owned by the coal company, so it wouldn’t work as a site. The county seat, Wilkes-Barre, was dismissed as a possibility because business leaders did not want it to be the place to “recall the deplorable labor troubles which it would be better to forget than to perpetuate in stone.” As late as the 1930s, newspapers still referred to the event at Lattimer as “the Lattimer riots.”

Opposition to the monument won out for most of the 20th century, with historical amnesia prevailing until the social and political unrest of the 1960s focused the nation on civil rights. Finally, in 1972, Pennsylvania governor Milton Shapp declared 1972 as “Lattimer Labor Memorial Year” and called upon Pennsylvania residents to remember and appreciate the efforts of the coal miners who had died. The historical roadside marker and memorial boulder were put in place, and dedicated to the memory of the miners on September 10, 1972. Union members from throughout the anthracite region and the country attended the event—as did Cesar Chavez, who spoke of a connection between the Eastern European miners and the United Farm Workers he led in California, many of whom were also “immigrants, who want to make a decent living in the United States.”

A memorial service has been held at the site annually ever since. In 1997, the centennial anniversary of the massacre, Pennsylvania dedicated a new state historical marker where the march began in Harwood, and another near the site of the massacre, adjacent to the “Rock of Solidarity.” The latter marker explains that the men were unarmed and marching for higher wages and equitable working conditions, and calls the killings “one of the most serious acts of violence in American labor history.”

Despite these efforts, Lattimer remains little known in the national public memory. The two state-sponsored historical markers still stand, a bit tarnished after decades of weathering, and the memorial boulder has a few new cracks, a testament to the fragility of the labor movement. There is now a new wave of migration to the area, mostly from Latin America. Many of today’s immigrants work in non-union meat packing plants or in fulfillment centers, racing up and down aisles gathering merchandise for delivery, all the while being timed for efficiency. The median income in the area is low, and these workers can face discrimination on the job and in their neighborhoods. Their story of struggle and perseverance—and Lattimer’s updated place in Pennsylvania and U.S. labor history—is slowly unfolding.

Paul A. Shackel is an anthropologist at the University of Maryland and author of Remembering Lattimer: Labor, Migration, and Race in Pennsylvania Anthracite Country.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.