When Theodore Roosevelt was 8 years old, he walked down the stairs of his parents’ brownstone mansion in Manhattan and set off toward a market near the city’s commercial hub on Broadway. Nobody paid attention to the delicate boy with teeth too large for his small round face, light hair and blue eyes. Known to his family as “Teedie,” Roosevelt was on a mission, much like the heroes of the books he read about faraway adventures and creatures unknown. He’d previously visited this morning’s destination while picking up strawberries for breakfast, but on this particular day in 1867, he was armed with more than a wicker basket. Inside his pocket were a folding wooden measuring stick and a blank notebook.

Roosevelt, who would later become one of the most famous American presidents in history, not to mention one of the world’s most celebrated conservationists, pushed his way through the crowd of shoppers, screaming peddlers and vendors. Then, he finally saw it: an enormous dead seal glistening in the morning sunlight. After a few days of pestering the shopkeeper who’d put the seal on display, Roosevelt convinced the man to give him the animal’s rapidly decaying head, which he carefully cleaned and preserved as the first specimen in his natural history collection.

Reflecting on the moment he initially saw the seal in his 1913 autobiography, Roosevelt wrote, “I remember distinctly the first day I started on my career as [a] zoologist.”

Roosevelt was born into a wealthy, upper-middle-class New York family in 1858. Though the family never lacked money or prestige, the future president and his three siblings suffered from bouts of poor health, including asthma, tuberculosis and spinal trouble. “I was a sickly, delicate boy, suffered much from asthma, and frequently had to be taken away on trips to find a place where I could breathe,” Roosevelt recalled in his autobiography. “One of my memories is of my father walking up and down the room with me in his arms at night when I was a very small person and of sitting up in bed gasping, with my father and mother trying to help me.” As a result of his ailments, the young boy spent very little time in public school; he was mainly tutored at home, first by his aunt and later by a French governess.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6d/0d/6d0d2c15-78e4-4038-8d26-dc0db60ff159/theodore_roosevelt_age_10.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4f/35/4f35f61b-51c0-4106-8d39-78e71f065fa3/age-7.jpg)

Roosevelt’s only escape from his sheltered upbringing was the world of boys’ adventure books, as introduced to him by his aunt. By age 7, he exhibited a predisposition toward nature and animals. From placing frogs under his hat and letting them leap out at people as he saluted them on the street to dropping small snakes into water glasses at the dinner table, the young Roosevelt felt much at home around odd creatures—at least the ones he could find in metropolitan New York.

A book by British author Thomas Mayne Reid sparked Roosevelt’s thirst for adventure and interest in natural history with its illustrations of mammals, which he later described as “pictures no more artistic than but quite as thrilling as those in the typical school geography.” Roosevelt also enthusiastically recalled scenes from Robinson Crusoe. In the Daniel Defoe novel, the titular character encounters wolves in the Pyrenees, nocturnal beasts bathing in the ocean, and pirates, all of which “simply fascinated” the young boy.

But these books paled in comparison with the large seal laid out on the wooden slab before him that morning in 1867. Roosevelt had never seen anything like it.

“That seal filled me with every possible feeling of romance and adventure,” he wrote of his repeated trips to the market to study the seal. Day in and day out, the shopkeeper allowed Roosevelt to ask questions and measure the animal in any way he could, all while recording the findings in his notebook. With each day, the boy’s instinctive interest in natural history transcended his childish thirst for adventure. And while his hopes of preserving the seal for further study failed to come to fruition, he did manage to secure its skull.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/82/40/8240ee06-5ce9-40d7-9942-d51d12330a2b/1280px-theodore_roosevelt_mountain_climbing_in_the_west1880_lccn2013650926.jpg)

“The adventure of the seal,” as Roosevelt would later refer to the event, kick-started a lifelong fascination that would eventually grow into a calling for natural preservation. The skull became the first of many specimens collected by the future president and two of his cousins for their “Roosevelt Museum of Natural History.” Soon, the collection grew, necessitating a move from the young Roosevelt’s bedroom to a bookcase in the upstairs hallway—much to the delight of the family’s chambermaid, who did not take to the young boy’s new passion and once even threw away a litter of mice he’d acquired.

Seeing their sickly child’s newfound obsession awaken within him a vigor and excitement for learning, Roosevelt’s parents encouraged his passion for natural history. The young boy’s father replaced his son’s rudimentary mammal book with a more comprehensive tome by J.G. Wood, an English author of popular volumes on natural history. “Today, we went down to the brook,” the 10-year-old Roosevelt noted in a journal entry. “In a small pond, … we saw crayfish, eels, minnows, salamanders, water spiders, water bugs, etc.” For Roosevelt, the great outdoors was no longer just for play but rather a tapestry of knowledge waiting to be discovered and absorbed.

At age 10, Roosevelt proudly watched his father, a prominent philanthropist, help establish the the Manhattan-based American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). One of the elder Roosevelt’s reasons for supporting the project was encouraging children such as his son who were interested in the natural sciences. By 11, the young boy boasted of having 1,000 scientific specimens in his room. He soon authored numerous amateur scientific essays on topics like the seal and insects.

In 1871, the now-teenage Roosevelt made his first donation to the AMNH, contributing a bat, 12 mice, a turtle, the skull of a red squirrel and 4 bird eggs. Eleven years later, in 1882, Roosevelt—by then a newly elected member of the New York State Assembly—made his first noteworthy donation as an adult, giving the majority of his Roosevelt Museum of Natural History collection, including 622 carefully preserved bird skins, to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/41/c741ffbc-f4a9-448f-b998-68d6240a2557/americanmuseumofnaturalhistory.jpg)

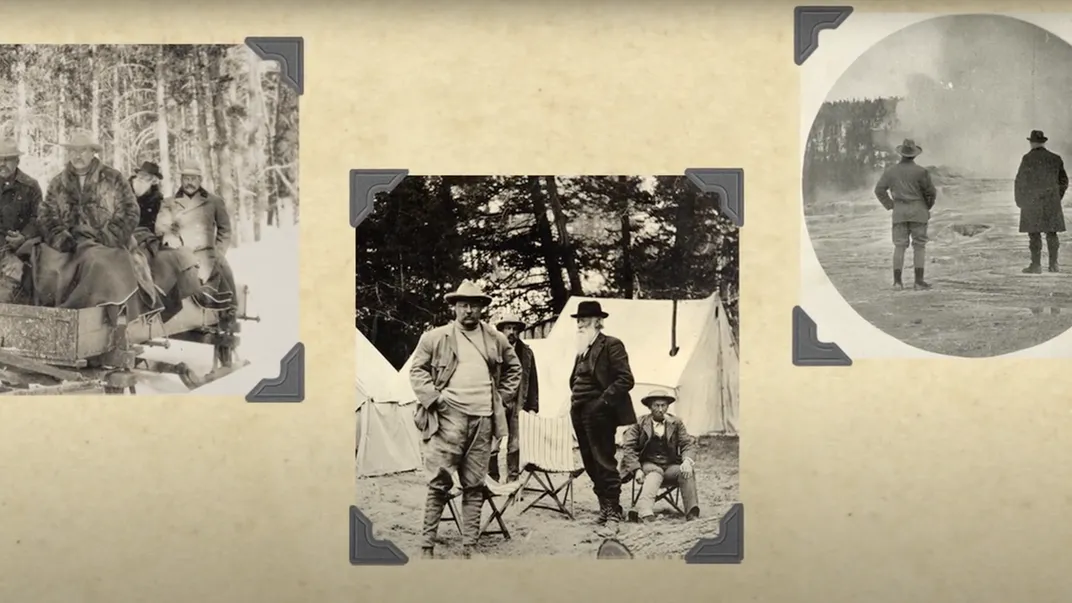

The conservationist ethos developed in Roosevelt’s youth continued to influence him throughout his life. From co-founding the Boone and Crockett Club, North America’s oldest wildlife conservation group, in 1887, to advocating for park and forestry programs as the governor of New York at the turn of the 20th century, Roosevelt never forgot the seal that sparked his interest in natural history.

In September 1901, Roosevelt, then serving as vice president, found himself thrust into the nation’s highest office by the assassination of President William McKinley. His subsequent eight-year stint in the White House is defined in large part by his environmental efforts. Often referred to as the “conservation president,” Roosevelt created the United States Forest Service and established 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, 4 national game preserves, 5 national parks and 18 national monuments under the Antiquities Act of 1906.

By the end of his presidency in March 1909, 50-year old Roosevelt was eager to seek out new adventures. Armed with nine pairs of glasses and a portable library, he sailed to North Africa by way of Naples, Italy, just a few weeks after leaving office. Roosevelt was accompanied by representatives of the Smithsonian, whose staff had eagerly accepted his offer to supplement the Institution’s lackluster African mammal collection with specimens shot by a former president. Now known as the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition, the yearlong trip was part hunting adventure, part natural history research venture. In total, Roosevelt and his son Kermit killed 512 animals during the expedition—a figure that, on the surface, might appear to clash with the commander in chief’s conservationist ideals.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f4/43/f443d92e-ce6c-4ce7-8851-b6d4b9e956b1/smithsonian_institution_archives_-_sia2009-1371.jpg)

“I am not in the least a game butcher,” Roosevelt wrote to Smithsonian Secretary Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1908. “I like to do a certain amount of hunting, but my real and main interest is the interest of a faunal naturalist.” Far from killing animals purely for sport, money or meat, he viewed hunting as a way of collecting natural history specimens for scientific study.

The president also advocated the fair chase doctrine, which became the basis of his Boone and Crockett Club. The philosophy emphasizes “the ethical, sportsmanlike, and lawful pursuit and taking of free-ranging wild game animals in a manner that does not give the hunter an improper or unfair advantage.” As Roosevelt wrote for Outing magazine in 1886, “To see the rapidity with which larger kinds of game animals are being exterminated throughout the United States is really melancholy.”

For Roosevelt, hunting for the preservation of information about the natural world, especially its animals, transcended pursuing it as a mere hobby. The Smithsonian expedition, much like his adventures as a young naturalist in his room, was about quenching his thirst for knowledge and perhaps helping others do the same though the various museum exhibitions that continue to amaze young and old to this day. In his own words, Roosevelt once said, “While my interest in natural history has added very little to my sum of achievement, it has added immeasurably to my sum of enjoyment in life.”

Roosevelt never forgot the New York museum that helped shape his early interest in conservation. His most significant donation to the AMNH came from a 1914 expedition to Brazil, which netted the museum more 3,000 specimens. Today, the AMNH is home to New York State’s official memorial to Roosevelt. Separately, an equestrian statue of the president, flanked by an African man on one side and a Native American man on the other, stood outside of the museum until 2022, when it was removed in response to accusations that it depicted “Black and Indigenous people as subjugated and racially inferior,” as Bill de Blasio, then mayor of New York, said in a 2020 statement.

Much like the man himself, Roosevelt’s legacy is complex. While he is still admired for his conservation efforts and progressive reforms while in office, his belief in a racial hierarchy and staunch imperialism continue to spark ongoing debate. It’s also worth noting that much of the land Roosevelt set aside as national parks was already under the care of the Native Americans who lived there.

“These areas were intimately known by the Indigenous people who traveled through and used [them],” Tabitha Erdey, then a cultural resources program manager for the Nez Perce National Historical Park, told History.com in 2022. Comparatively, “Euro-Americans saw these areas as wilderness, as empty spaces that were in need of civilization and control.”

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/06/de066803-ff20-4116-8e49-7e0dab59c101/seal.jpg)