How the Abduction of Patty Hearst Made Her an Icon of the 1970s Counterculture

A new book places a much-needed modern-day lens on the kidnapping that captivated the nation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/0b/5e0b50a8-98a4-4fa9-ba55-57e308e87cee/pattyhearstmug.jpg)

The 1970s were a chaotic time in America. One of the decade’s most electrifying moments, magnifying flashpoints in American politics, culture and journalism, was the abduction of newspaper heiress Patricia “Patty” Campbell Hearst in early 1974.

The headline-grabbing spectacle only added to the wave of disastrous political, economic and cultural crises that engulfed America that year. The Watergate scandal had intensified as President Nixon vehemently denied knowledge of the illegal break-in to the Democratic National Committee headquarters. The economy continued to stagnate as inflation hit 12 percent and the stock market lost close to half its value. The oil crisis deepened, with long lines at the gas pump and no sign of reprieve. Radical counterculture groups continue to detonate bombs across the country, with approximately 4,000 bombs planted in America between 1972-1973. And, in Hearst’s home city of San Francisco, authorities still worked desperately to identify the infamous “Zodiac” killer who had already slaughtered five people (but suspected of killing dozens more) and yet continued to remain at-large.

In the midst of this destabilized climate came the Hearst kidnapping. The abduction itself was one of the few instances in modern history when someone as wealthy and reputable as a Hearst was kidnapped, simultaneously catapulting one young college student and America’s radical countercultural movements to national prominence. Spread out over several years, the Hearst “saga” came to underscore a rift in American society, as younger generations grew increasingly disillusioned with a political system bequeathed by their elders who were seemingly unwilling to address the nation’s economic and social instability.

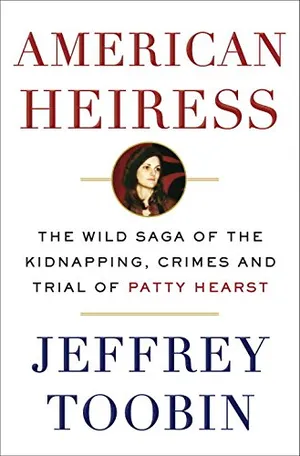

The infamous kidnapping is now the subject Jeffrey Toobin’s new book America Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trials of Patty Hearst. (Hearst has always hated being known as “Patty,” a pet name originally bestowed on her by her father that has trailed her ever since.) The New Yorker writer retraces the kidnapping and criminal case of Hearst and her life of the lam, offering fresh insights into this truly mythic tale. Unlike previous accounts on the Hearst story, Toobin interrogates Hearst’s criminal stardom in the wake of the abduction, exploring how she paradoxically became a poster-girl for the decade’s rampant counterculture and fierce anti-establishment sentiment as well as a “common criminal” who “had turned her back on all that was wholesome about her country.”

Patricia was the granddaughter of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst, the founder of one of the largest network of newspapers in America and also the inspiration for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. Although Patricia was born into the Hearst dynasty, William Randolph left a sizable chunk to each of his five sons (including Patricia’s father, Randolph), but entrusted the majority of wealth to the trustees of the Hearst Corporation. Only 19 years old, Hearst was a relatively innocuous figure, but also a representation of the wealth and power structures that the counter-culture wanted to usurp.

The saga all started when a small and little-known, disorganized guerrilla group called the “Symbionese Liberation Army” (SLA) chose Hearst, then a sophomore at University of California, Berkeley, to kidnap. They had hoped the abduction would not only bring attention to their group’s radical cause but that Hearst herself could be used as a bargaining chip to free former SLA comrades incarcerated in prison. (The name “Symbionese” referred to the group’s idea of “political symbiosis,” in which segregated political movements such as gay liberation and Marxism worked together in harmony to achieve socialist ends.) On February 4, 1974, a band of five people broke into Hearst’s apartment—a location they easily discovered after consulting the university’s public registrar—wielding guns and spewing violent threats. They grabbed Hearst and stuffed her in the back of a stolen car as her fiancé ran out screaming and fleeing in terror.

Three days later, the SLA sent a letter to a nearby Berkeley radio station announcing that they had taken Hearst and were now holding her hostage as a “prisoner of war,” sparking a media frenzy. The organization demanded that in exchange for her release, Patricia’s father must feed the entire population of Oakland and San Francisco for free, a seemingly impossible task. But after haphazard attempts by her family to feed the entire Bay Area—coupled with two months of inconsistent and bizarre political “communiqués” from the SLA—Hearst herself announced to the world that was she was doing the unimaginable: she was joining her kidnappers in their campaign to cause political unrest in America. Patricia adopted the name “Tania” and, among other illicit activities, robbed a bank with the SLA.

In an effort to prove her complete conversion and ignite interest in their fight, the SLA chose to rob a local bank, not just because they needed the money, but also because the robbery itself would be recorded on surveillance tape. With visual evidence of Hearst committing crimes, they could leverage that into more media coverage. As more Americans began consuming news from television, and less from evening or afternoon newspapers, the SLA understood that the impact the security camera footage would make.

Additionally, Hearst’s symbolic tie to the history of American journalism allowed the SLA to exploit the news media’s tendency to navel gaze, monopolizing press coverage across all formats and turning their criminal activities into a national sensation.

After criss-crossing the nation with her comrades for more than a year, Hearst was finally captured in September 1975, charged with armed robbery. Her trial became a media circus; the legitimacy of the “Stockholm syndrome,” the psychological condition in which a kidnapped victim begins to identify closely with their captors, quickly became the focus of the proceedings. (It takes its name from a high-profile bank hostage case in Stockholm one year earlier, in which several of the bank’s employees closely bonded with their captors.)

Critics of Hearst’s “Stockholm syndrome” defense pointed to multiple audio recordings in which Hearst apparently spoke calmly and lucidly about her decision to defect, all under her own “free will.” But to others, Hearst was a textbook case of the condition, only joining her kidnappers because of the intense strain and trauma of her abduction, physically and psychologically unravelling in such isolated captivity. Whether or not she acted under duress did not sway the judge, with Hearst found guilty and sentenced to seven years’ in prison in 1976.

Hearst’s defection and subsequent criminal spree has long helped enshrine her story into modern American history. To Toobin, there are endlessly conflicting accounts of Hearst’s actual decision to defect, including inconsistencies in her court testimony and police confessions. “Patricia would assert that her passion for joining was a subterfuge because she truly believed that the real choice was join or die,” he writes.

Toobin notes how the abduction was originally treated as a celebrity spectacle; Patricia’s face dominated magazine covers with headlines like “Heiress Abducted,” portrayed as a young and innocent socialite imprisoned by hardcore radicals. But he argues that when she defected, she soon morphed into icon for many young and disillusioned Americans who came to identify with her anti-establishment escapades and her desire to shake off the “corrupt” life she had been raised in. As someone who had grown up in the lap of luxury—indeed from a family immune to the many of the grim economic and political realities of the times—Hearst’s decision to stay with her kidnappers was a deeply symbolic transgression, one that articulated the anger so many felt against the American establishment.

Unlike the already enormous body of writing on the topic, Toobin’s study shows acute awareness of the underlying tensions operating in the larger culture, much of which helped to shape how the American public perceived the spectacle. “[The] saga was caught up in the backlash against the violent and disorder of the era,” writes Toobin. But after her capture after being on the run, public opinion swayed significantly against her. “By 1975, she was a symbol no longer of wounded innocence but rather of wayward youth.” Although Toobin had no participation from Hearst—she refused to be involved in the project—his history nevertheless connects the forces of the counterculture, Hearst’s amorphous public identity, and alienation that not even Hearst’s own account (published as Every Secret Thing in 1981) could offer.

Much like his study of the O.J. Simpson trial, For The Run of His Life (recently adapted into the FX television series), Toobin works off a similar strategy, unpacking the paradoxes of Hearst’s title of “criminal celebrity.” In much the same way the O.J. Simpson trial became a symbol of the racial tensions of the 1990s, representing the gulf between the experiences of white and black America, the Hearst abduction story later acted as an emblem of the 1970s. Toobin underscores the widespread and near-contagious disillusionment for the decade, one that saw the ideological pressures map across perceptions of government, growing economic instability, and a pervasive and increasingly popular counterculture movement.

But unlike O.J., Simpson, whose star image is now inextricably bound to his individual, violent crimes, Hearst’s public image at the time (and now) are seen to be less personal and more indicative for the psychosis of the era. After President Carter commuted Hearst’s sentence to 22 months, she avoided remaining a public figure, marrying her bodyguard Bernard Shaw and attempting to begin a normal life out of the spotlight—one, importantly enough, far closer to her Hearst origins than her SLA escapades. She released her memoir in an attempt to end further attention to her case and distance herself from her criminal celebrity. Interest in Hearst waned as the 1980s left many of the issues of the previous decade behind.

American Heiress argues the kidnapping was ultimately “very much a story of America in the 1970s … provid[ing] hints of what America would later become.” Patricia “Patty” Hearst became an unlikely figure for the decade, not only because she had so publically experienced an unthinkable trauma, but also because she symbolically pointed out fissures in American life—tensions that ultimately came to be permanent hallmarks of the times.