How (Almost) Everyone Failed to Prepare for Pearl Harbor

The high-stakes gamble and false assumptions that detonated Pearl Harbor 80 years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/13/4913ccd4-90c5-4656-b4b0-504b85f30085/dec2016_k02_pearlharbor.jpg)

The dawn watch had been as pacific as the ocean at their feet. Rousted by an alarm clock, Pvts. George E. Elliott Jr. and Joseph L. Lockard had awakened in their tent at 3:45 in the caressing warmth of an Oahu night and gotten their radar fired up and scanning 30 minutes later. Radar was still in its infancy, far from what it would become, but the privates could still spot things farther out than anyone ever had with mere binoculars or telescope.

Half a dozen mobile units—generator truck, monitoring truck, antenna and trailer—had been scattered around the island in recent weeks. George and Joe’s, the most reliable of the bunch, was emplaced farthest north. It sat at Opana, 532 feet above a coast whose waves were enticing enough to surf, which is what many a tourist would do there in years to come. Army headquarters was on the other side of the island, as was the Navy base at Pearl Harbor, the most important American base in the Pacific. But between the privates and Alaska, 2,000 miles away, there was nothing but wavy liquid, a place of few shipping lanes and no islands. An Army general called it the “vacant sea.”

The order of the day was to keep vandals and the curious away from the equipment during a 24-hour shift and, from 4 a.m. to 7 a.m., sit inside the monitoring van as the antenna scanned for planes. George and Joe had no idea why that window of time was significant. Nobody had told them. The two privates had been ordered out there for training. “I mean, it was more practice than anything else,” George would recall. Often with the coming of first light and then into the morning, Army and Navy planes would rise from inland bases to train or scout. The mobile units would detect them and plot their locations. Between them, George and Joe had a couple of .45-caliber pistols and a handful of bullets. The country had not been at war since November 11, 1918, the day the Great War ended, and the local monthly, Paradise of the Pacific, had just proclaimed Hawaii “a world of happiness in an ocean of peace.”

Joe, who was 19 and from Williamsport, Pennsylvania, was in charge of the Opana station that morning, and worked the oscilloscope. George, who was 23 and had joined the Army in Chicago, was prepared to plot contacts on a map overlay and enter them in a log. He wore a headset connecting him to Army headquarters.

George and Joe had detected nothing interesting during the early-morning scan. It was, after all, a Sunday. Their duty done, George, who was new to the unit, took over the oscilloscope for a few minutes of time-killing practice. The truck that would shuttle them to breakfast would be along soon. As George checked the scope, Joe passed along wisdom about operating it. “He was looking over my shoulder and could see it also,” George said.

On their machine, a contact did not show up as a glowing blip in the wake of a sweeping arm on a screen, but as a spike rising from a baseline on the five-inch oscilloscope, like a heartbeat on a monitor. If George had not wanted to practice, the set might have been turned off. If it had been turned off, the screen could not have spiked.

Now it did.

Their device could not tell its operators precisely how many planes the antenna was sensing, or if they were American or military or civilian. But the height of a spike gave a rough indication of the number of aircraft. And this spike did not suggest two or three, but an astonishing number—50 maybe, or even more. “It was the largest group I had ever seen on the oscilloscope,” said Joe.

He took back the seat at the screen and ran checks to make sure the image was not some electronic mirage. He found nothing wrong. The privates did not know what to do in those first minutes, or even if they should do anything. They were off the clock, technically.

Whoever they were, the planes were 137 miles out, just east of due north. The unknown swarm was inbound, closing at two miles a minute over the shimmering blue of the vacant sea, coming directly at Joe and George.

It was just past 7 in the morning on December 7, 1941.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/ac/09ac3326-583c-4241-abac-bdbe4cf8fe48/dec2016_k01_pearlharbor.jpg)

**********

The attack on Pearl Harbor, 80 years ago this month, was the worst day in the U.S. Navy’s history and the shock of a lifetime for just about any American who had achieved the age of memory. Although the disaster destroyed the careers of both the Navy and the Army commanders on Oahu, exhaustive investigations made it clear that its causes went beyond any individual in Hawaii or Washington, D.C. Intelligence was misread or unshared. Vital communiqués were ambiguous. Too many search planes had been diverted to the Atlantic theater.

Most devastating, Americans simply underestimated the Japanese. Their success at Pearl Harbor was due partly to astounding good luck, but also to American complacency, anchored in two assumptions: that our Asian adversary lacked the military deftness and technological proficiency to pull off an attack so daring and so complicated, and that Japan knew and accepted that it would be futile to make war on a nation as powerful as the United States. Even now, in the age of terror, the basic lesson of Pearl Harbor remains apt: When confronting a menacing opponent, you have to shed your own assumptions and think like him.

The architect of the attack was a diminutive admiral of 57 years, with gray close-cut hair and a deep fondness for Abraham Lincoln. Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander in chief of Japan’s Combined Fleet, stood only three inches taller than five feet and weighed 130 pounds, maybe. Geishas who did his fingernails called him Eighty Sen because the regular rate was ten sen a finger and he had only eight fingers, having given the left middle and index to vanquish the Russians in the war of 1904-5.

Yamamoto did not drink much, but he bet a lot. He could beat good poker players, good bridge players and win at Go, the ancient East Asian strategic board game. Roulette, pool, chess, mah-jongg—you’d pick and he’d play and he’d win. “Few men could have been as fond of gambling and games of chance as he,” one Japanese admiral said. “Anything would do.” Yamamoto bested subordinates so often he would not cash their checks. If he had, they would have run out of betting money, and he would have run out of people to beat.

As proud of his country as anyone of his generation, as eager to see Westerners pay some long-overdue respect to the Empire’s power and culture, Yamamoto nonetheless had opposed its 1940 alliance with Nazi Germany and Italy. That hardly endeared him to Japan’s extreme nationalists but did not dent his renown.

In planning the Pearl Harbor attack, Yamamoto knew full well the power of his adversary. During two tours in the United States, in 1919 and 1926, he had traveled the American continent and noted its energy, its abundance and the character of its people. The United States had more steel, more wheat, more oil, more factories, more shipyards, more of nearly everything than the Empire, confined as it was to rocky islands off the Asian mainland. In 1940, Japanese planners had calculated that the industrial capacity of the United States was 74 times greater, and that it had 500 times more oil.

If pitted against the Americans over time, the Imperial Navy would never be able to make up its inevitable losses the way the United States could. In a drawn-out conflict, “Japan’s resources will be depleted, battleships and weaponry will be damaged, replenishing materials will be impossible,” Yamamoto would write to the chief of the Naval General Staff. Japan would wind up “impoverished,” and any war “with so little chance of success should not be fought.”

But Yamamoto alone could not stop the illogical march of Japanese policy. The country’s rapacious grab for China, now in its fifth year, and its two bites of French Indochina, in 1940 and 1941, had been answered by Western economic sanctions, the worst being the loss of oil from the United States, Japan’s principal supplier. Unwilling to give up greater empire in return for the restoration of trade, unwilling to endure the humiliation of withdrawal from China, as the Americans demanded, Japan was going to seize the tin, nickel, rubber and especially oil of British and Dutch colonies. It would take the Philippines, too, to prevent the United States from using its small naval and land forces there to interfere.

Just 11 months before Privates Elliott and Lockard puzzled over the spike on their oscilloscope, Yamamoto set down his thoughts about a bold course by which to attack the United States. War with the Americans was “inevitable,” Yamamoto had written. Japan, as the smaller power, must settle it “on its first day” with a strike so breathtaking and brutal that American morale “goes down to such an extent that it cannot be recovered.”

But how? As with every innovation, someone gets there first. In this case, the Japanese led the world in appreciating the lethal possibilities of massed aircraft carriers. They still had battleships—the backbone of navies since cannon had made their way to wooden decks in the Age of Sail—but battleships and cruisers had to move to within sight of the enemy to sink him. Aircraft carriers could lurk 100, even 200, miles away, far beyond the range of any battleship gun, and send dive bombers and torpedo bombers to attack their unsuspecting adversary. And having a mass of carriers sail as one and launch simultaneously, rather than sail scattered or alone, dramatically enhanced their destructive power.

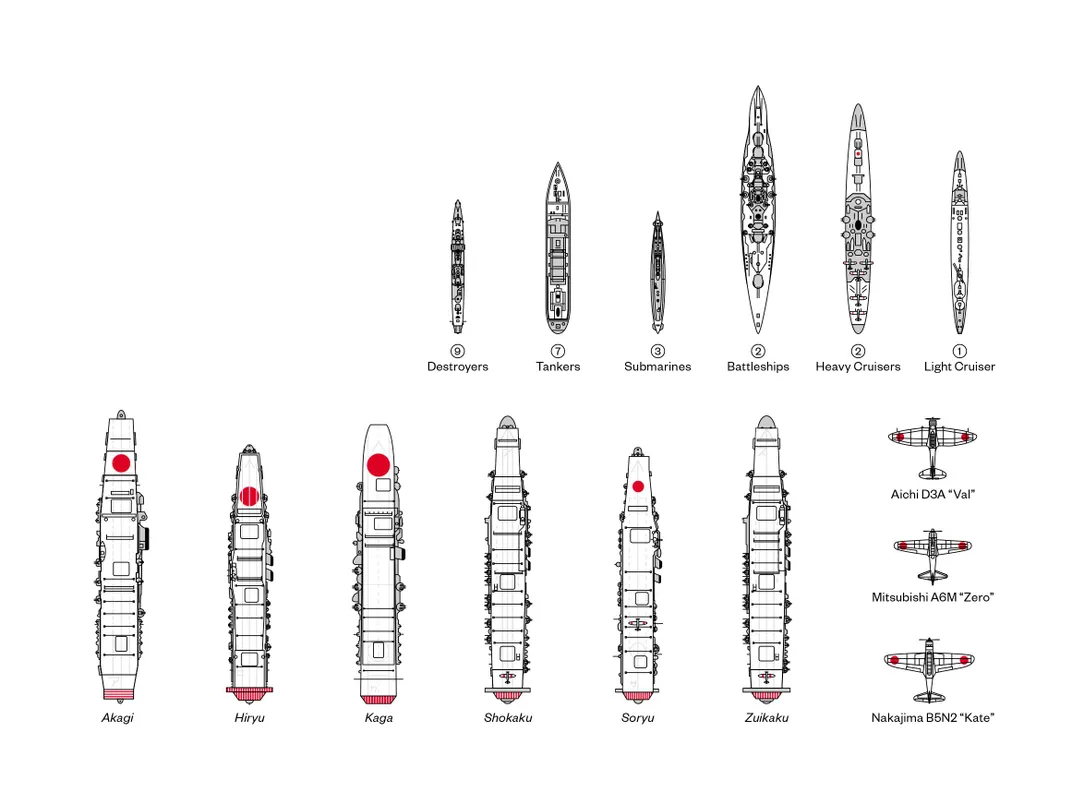

By the end of 1941, Japan had built ten aircraft carriers, three more than the United States. Yamamoto planned to send six of them 3,150 nautical miles across the vacant north Pacific and into battle off Hawaii.

After outlining his attack in impeccable handwriting on three pages of high-quality paper in January 1941, Yamamoto sent it to a subordinate admiral, who shared it with a military pilot. “For one week, I forgot sleeping and eating,” recalled the pilot, Minoru Genda, Japan’s leading apostle of seaborne air power, who helped refine and then execute the plan. Raiding Pearl Harbor, he thought, would be “like going into the enemy’s chest and counting his heartbeat.” Evaluating the idea was “a great strain on the nerves. The most troubling thing was to keep the plan an absolute secret.” Yamamoto’s grand bet would work only if the Americans lived in ignorance through the last days of peace as the strike force sneaked to the edge of Hawaii. Eventually, Genda concluded it could be done.

Others thought not.

The naval hierarchy in Tokyo rained doubt upon a Pearl Harbor raid. Many questions could not be answered by war games or staff research, only by going through with it. Yamamoto could not guarantee that the Pacific Fleet would be in port on the planned day of attack. If it had sailed away on an exercise, the strike fleet would be exposed far from home with the enemy’s naval power intact and whereabouts uncertain. Nor could he guarantee that his men could pull off the dozens of tanker-to-warship refuelings essential to getting the strike fleet into battle and back. The north Pacific becomes tempestuous as autumn gives way to winter; the fleet’s supply tankers would run a risk each time they sidled close to string hoses and pump their flammable contents.

Mostly, achieving surprise—the sine qua non of Yamamoto’s vision—seemed an absurd hope. Even if there were no leaks from the Imperial Navy, the north Pacific was so vast that the strike fleet would be in transit almost two weeks, during which it might be discovered any minute. The Japanese assumed American patrols would be up, flying from Alaska, from Midway Island, from Oahu; their submarines and surface ships would scour the seas. Unaware they had been spotted, the Japanese might sail valiantly to their destruction in a trap sprung by the very Pacific Fleet they had come to sink.

Success for Yamamoto’s raiders seemed 50-50, at best 60-40. Failure might mean more than the loss of ships and men. It might jeopardize Japan’s plan to conquer Malaya, Singapore, the Netherlands East Indies and the Philippines that fall. Instead of adding a mission to Hawaii that might wipe out much of the Imperial Navy, many officers preferred to leave Pearl Harbor alone.

Nothing punctured Yamamoto’s resolve. “You have told me that the operation is a speculation,” he told another admiral one day, “so I shall carry it out.” Critics had it backward, he argued: The invasions of British, Dutch and American colonies would be jeopardized if the Imperial Navy did not attack Pearl Harbor. Leaving the Pacific Fleet untouched would concede the initiative to the Americans. Let us choose the time and the place for war with the Pacific Fleet.

For Yamamoto, the place was Pearl and the time was immediately after—an hour or two after—the Empire submitted a declaration of war. He believed that an honorable samurai does not plunge his sword into a sleeping enemy, but first kicks the victim’s pillow, so he is awake, and then stabs him. That a non-samurai nation might perceive that as a distinction lacking a difference did not, apparently, occur to him.

Attacking Pearl would be the biggest bet of his life, but Yamamoto considered it no more dangerous than his country’s plan to add Britain, the Netherlands and the United States to its roster of enemies. “My present situation is very strange,” he wrote on October 11 to a friend. He would be leading the Imperial Navy in a war that was “entirely against my private opinion.” But as an officer loyal to His Majesty the Emperor, he could only make the best of the foolish decisions of others.

In the end, he prevailed over the critics. By late November, the strike fleet had assembled in secret at Hitokappu Bay, off one of the most desolate and remote islands in the Kurils. Two battleships. Three cruisers. Nine destroyers. Three submarines. Seven tankers. Six aircraft carriers. On November 23, as the attack plan was passed through to the enlisted men and the lower-rank officers, many exulted. Others began writing wills. A pilot named Yoshio Shiga would tell an American interrogator just how dubious the aviators were. “Shiga stated that the consensus...following this startling news was that to get to Hawaii secretly was impossible,” the interrogator would write, summarizing an interview conducted a month after the war’s end. “Hence, it was a suicide attack.”

At six o’clock in the morning of Wednesday, November 26, under a sky of solid pewter, the temperature just above freezing, anchors ascended from the frigid waters, propeller shafts began spinning and the strike fleet crept into the Pacific. Aboard the carrier Akagi was Minoru Genda, his faith in naval air power validated all around him. Working for many weeks on the fine points of the attack—how many planes, what mix of planes, what ordnance, how many attack waves—he had struggled most of all with an immutable characteristic of Pearl Harbor, its depth. Forty-five feet was not enough, not for the weapon of greatest threat to a ship’s hull.

Dropped from a plane, the typical torpedo in any navy plunged deeper than 45 feet, so instead of leveling off and racing toward an American ship, the weapon would bury itself in Pearl Harbor’s muddy bottom unless somebody thought of a way to make the plunge much shallower. Only in mid-November had the Japanese thought to add more stabilizing fins to each 18-foot weapon to prevent it from spinning as it plummeted from plane to sea. That would reduce how deeply it plunged. “Tears came to my eyes,” Genda said. There was, though, still the chance that the Americans would string steel nets around their anchored ships to thwart torpedoes. The pilots could not be sure until they arrived overhead.

Gradually, the strike fleet spread out, forming a box roughly 20 miles across and 20 deep, a line of destroyers out front, cruisers and tankers and more destroyers in the middle, the carriers and the battleships at the rear. The fleet would sail nearly blind. It did not have radar, and no reconnaissance planes would be sent aloft, because any scout who became lost would have to break radio silence to find his way back. There would only be three submarines inspecting far ahead. The fleet would sail mute, never speaking to the homeland. Radio operators would listen, however. One message would be Tokyo’s final permission to attack, if talks in Washington failed.

No navy had collected so many carriers into a single fleet. No navy had even created a fleet based around aircraft carriers, of any number. If the Japanese reached Hawaii undetected and intact, nearly 400 torpedo bombers, dive bombers, high-altitude bombers and fighter planes would rise from the flight decks of the Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, Soryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku and deliver the largest and most powerful airborne assault from the sea ever.

**********

Unaware that a secret fleet was on its way to Hawaii, the Americans did know—from the volume of radio traffic, from observers in the Far East—that many other Imperial warships were moving toward the Philippines and the rest of Southeast Asia. On November 27, the day after the strike fleet moved out of Hitokappu Bay, a message from Harold Stark, the chief of naval operations in Washington, flashed to all U.S. Navy outposts in the Pacific:

This dispatch is to be considered a war warning X Negotiations with Japan looking toward the stabilization of conditions in the Pacific have ceased and an aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days X The number and equipment of Japanese troops and the organization of naval task forces indicates an amphibious expedition against either the Philippines Thai or Kra Peninsula or possibly Borneo X Execute an appropriate defensive deployment preparatory to carrying out the tasks assigned in WPL46.

The message contained rich dollops of intelligence—war is imminent, talks have ended, Japanese landings could happen here, here and here—but only one order: execute an appropriate defensive deployment so you can carry out the prevailing war plan. Left out, deliberately, was any hint of what qualified as that sort of deployment, whether taking ships to sea, elevating watch levels, sending protective fighter planes aloft or something else. That decision was left to the recipients. Fleet commanders had gotten their jobs by demonstrating judgment and leadership. If Harold Stark endorsed a single managerial tenet above all others, it was to tell people what you want done, but not how to do it. People loved him for it.

In Manila—4,767 nautical miles from Pearl Harbor—it was already November 28 when Stark’s warning reached the commander of the small Asiatic Fleet, Adm. Thomas Charles Hart. “Really, it was quite simple,” recalled Hart, whom Time magazine described as a “wiry little man” who was “tough as a winter apple.” The war warning meant that “we were to await the blow, in dispositions such as to minimize the danger from it, and it was left to the commanders on the spot to decide all the details of said defensive deployment.” Outnumbered and sitting only a few hundred miles from the nearest Japanese bases, Hart began to scatter his submarines, and his surface ships began to put to sea. A wise man in his situation, he said, “sleeps like a criminal, never twice in the same bed.”

The Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, on the other hand, enjoyed serious distance from the adversary, days and days of it. Given the number of Fleet battleships (9), aircraft carriers (3), cruisers (22), destroyers (54), submarines (23) and planes (hundreds), it could defend itself, too.

All through the year to that point, the commander of the Pacific Fleet, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, had received alarming dispatches from Washington about possible Japanese aggression. He had gotten so many, in fact, that Vice Adm. William F. Halsey, who commanded the Fleet carriers and would become a figure of lore in the coming war, called them “wolf” dispatches. “There were many of these,” Halsey said, “and, like everything else that’s given in abundance, the senses tended to be dulled.”

The Navy had long-range seaplanes on Oahu, but the PBYs, as the floatplanes were known, had never been deployed for systematic, comprehensive searches of the distant perimeter. They only scoured the “operating areas” where the Fleet practiced, usually south of Oahu, as a precaution against a Japanese submarine taking a stealthy, peacetime shot during those exercises. But those sweeps covered only a slim arc of the compass at a time. Kimmel, the very picture of an admiral at two inches shy of six feet, with blue eyes and sandy-blond hair sliding toward gray at the temples, said that if he had launched an extensive search every time he received a warning from Stark, his men and machines would be so burned out they would be unfit to fight. He had to have solid information that the Japanese might be coming for him before he would launch his search planes.

As they read Stark’s latest alarum on November 27, Kimmel and his officers were taken aback by the phrase “war warning,” as Stark had hoped they would be. “I not only never saw that before in my correspondence with the Chief of Naval Operations,” Kimmel said, “I never saw it in all my naval experience.” Likewise, execute an appropriate defensive deployment struck everyone as an odd phrase because, as one officer said, “We do not use that term in the Navy.” But because the overall warning message never mentioned Hawaii—only places far away, near Admiral Hart—Kimmel and his men saw no imminent threat.

Neither did the Army on Oahu. On the same day as Kimmel, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, the Army commander, got a war warning of his own from Washington. The sending of two dispatches to Oahu, one per service, reflected the peculiar reality that no single person commanded the military there. The duality could easily lead to poor assumptions about who was doing what, and it did.

Seeing nothing in the Army’s warning about a threat to Oahu, Short opted to guard not against an external threat, but against saboteurs who might be lurking among the thousands of Oahu residents of Japanese descent. An Army officer would say afterward, however, he had always believed “that we would never have any sabotage trouble with the local Japanese. And we never did.”

As for the Pacific Fleet, it would carry on as before. It was not yet time to empty Pearl of as many ships as possible. It wasn’t time to hang torpedo nets from any that remained because everyone knew the harbor was too shallow for torpedoes. The harbor outside Kimmel’s office windows might have been an ideal refuge for ships in an earlier era, but not in the age of the warplane. Even landlubber Army officers knew that. “All you had to do was drive by down here when the Fleet was all in,” Short said. “You can see that they just couldn’t be missed if they had a serious attack....There was too little water for the number of ships.”

**********

Japan’s absurd hope was met: Its strike fleet sailed the Pacific for 12 days without being detected, right up until Privates Elliott and Lockard saw the spike on their oscilloscope on the morning of December 7. The spike represented the leading edge of the attack, 183 planes. There had never been anything remotely like it in the history of warfare—and some 170 more planes would follow, as soon as they were elevated from hangar decks to the cleared fight decks.

Only after some debate did the privates decide to tell someone in authority. When they contacted the information center at Fort Shafter, the Army’s palm-strewn grounds a few miles east of Pearl Harbor, they were told to forget about it. They watched the oscilloscope as the unidentified planes closed the distance. At 15 or 20 miles out, with the radar now getting return echoes from Oahu itself, the cluster vanished in the clutter.

A Japanese communiqué to the United States, intended as a warning for the attack, was timed for delivery in Washington by 1 p.m. December 7, or 7:30 a.m. in Hawaii. But it was delayed in transmission until after the attack had begun.

It was 7:55 in Hawaii when Admiral Kimmel, his uniform not yet buttoned, stepped into his yard, overlooking Pearl. Aircraft were descending, climbing, darting, unmistakable red balls painted on every wing. Every resident of Oahu was accustomed to seeing military planes overhead, but only their own, and for the rest of their lives they would speak of the shock of those alien red spheres, the Japanese flying over the United States. Kimmel’s next-door neighbor joined him in the yard, two helpless witnesses to budding catastrophe. To her, the admiral seemed transfixed, incredulous, his face “as white as the uniform he wore.”

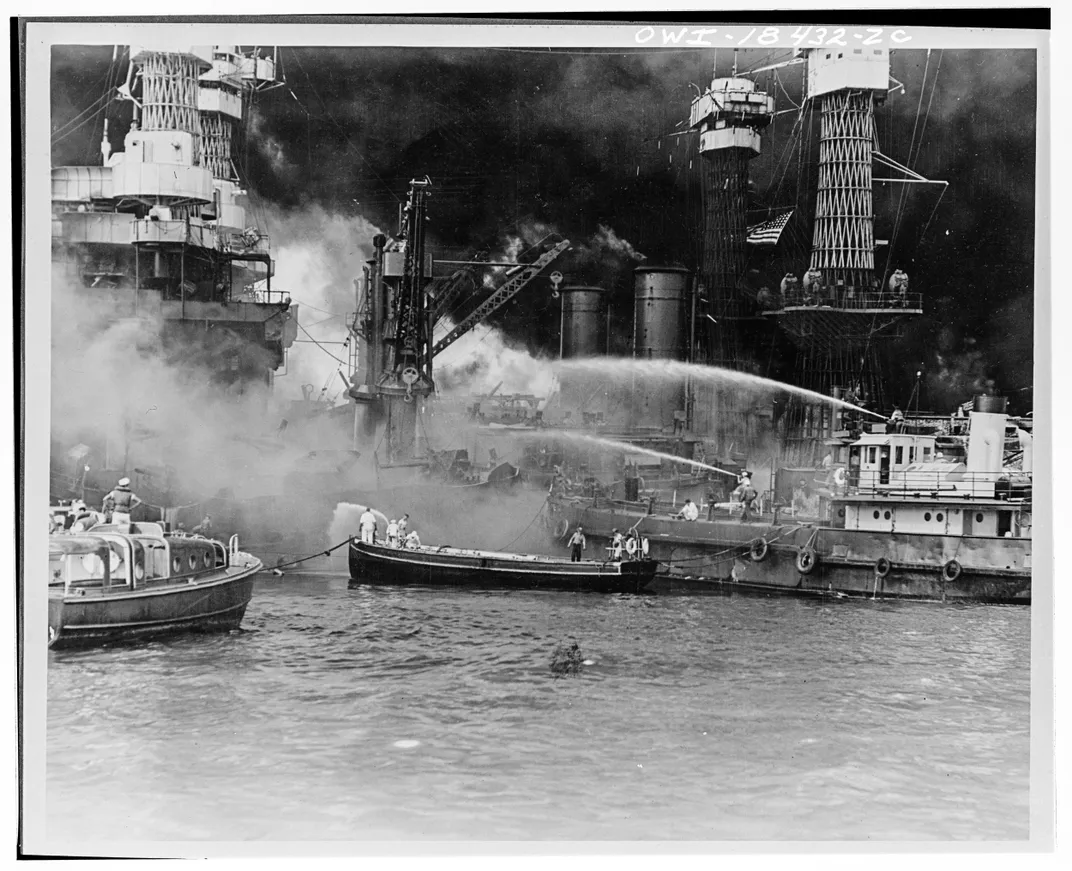

Torpedo bombers skimmed directly past Fleet headquarters to drop their 2,000-pound weapons, which did not impale in the mud but rose, leveled off and raced beneath the harbor’s surface until they smashed into the hulls of Battleship Row, where there were no torpedo nets. Three pierced the California, opening gaping holes. A half-dozen riddled the West Virginia, which began to tip sharply to port; three, four, then more punctured the Oklahoma, which overturned in minutes, trapping hundreds of men within; one hit the Nevada. When a bomb blasted the Arizona's forward magazine, the ship disappeared in a thousand-foot mountain of boiling, bluish-purple smoke.

At 8:12, Kimmel, having been driven to his headquarters, radioed the first true communiqué of the fledgling Pacific war, addressed to the Fleet—his carriers happened to be elsewhere, and needed to know—and to the Navy Department. “Hostilities with Japan commenced with air raid on Pearl Harbor,” which conveyed the idea the attack had concluded. It was just beginning.

Yet out there in the harbor, something deeply heroic was taking place. Through the ten months he had commanded at Pearl Harbor, Kimmel had insisted on endless training, on knowing the proper thing to do and the proper place to be; now that training was becoming manifest. His men began shooting back, from the big ships, from the destroyers and cruisers, from rooftops and parking lots, from the decks of the submarines right below his windows. Within five minutes or less, a curtain of bullets and anti-aircraft shells began rising, the first of 284,469 rounds of every caliber the Fleet would unleash. An enraged enlisted man threw oranges at the enemy.

The Japanese planes kept coming in waves that seemed endless but lasted two hours. Amid the maelstrom, a bullet from an unknown gun, its velocity spent, shattered a window in Kimmel’s office and struck him above the heart, bruising him before tumbling to the floor. A subordinate would remember his words: “It would have been merciful had it killed me.”

By the end, 19 U.S. ships lay destroyed or damaged, and among the 2,403 Americans dead or dying were 68 civilians. Nothing as catastrophically unexpected, as self-image-shattering, had happened to the nation in its 165 years. “America is speechless,” a congressman said the next day, as the smell of smoke, fuel and defeat hovered over Pearl. Long-held assumptions about American supremacy and Japanese inferiority had been holed as surely as the ships. “With astounding success,” Time wrote, “the little man has clipped the big fellow.” The Chicago Tribune conceded, “There can be no doubt now about the morale of Japanese pilots, about their general abilities as fliers, or their understanding of aviation tactics.” It was now obvious the adversary would take the risks that defied American logic and could find innovative ways to solve problems and use weapons. The attack was “beautifully planned,” Kimmel would say, as if the Japanese had executed a feat beyond comprehension.

But Yamamoto was correct: Japan had begun a war it could never win, not in the face of the industrial might of an enraged and now-wiser America. The military damage of the attack—as opposed to the psychological—was far less than first imagined. Feverish repairs on the battleships commenced, in Hawaii and then on the West Coast. The Fleet would exact its revenge shortly, at the Battle of Midway, when American carrier pilots sank four of the Japanese carriers that had shocked Pearl. And on September 2, 1945, the battleship West Virginia, now recovered from the wounds of December 7, stood among the naval witnesses to the surrender of the Japanese in Tokyo Bay.

Related Reads

Countdown to Pearl Harbor: The Twelve Days to the Attack