How America Became Obsessed With Horses

A new book explores the meaning the animal holds for people—from cowboys to elite show jumpers—in this country

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/36/b9366636-38f6-4c85-a92e-1eee36ddb5de/assateauge_wild_ponies_on_parade.jpg)

To Sarah Maslin Nir, a horse isn’t just a horse. The New York Times journalist and Pulitzer Prize finalist sees the ungulate as "a canvas on which we’ve painted American identity.”

The United States today is home to over 7 million horses, more than when they were the country’s primary means of transportation, and one of the largest horse populations in the world. Nir’s new book, Horse Crazy, is an exploration of this national obsession and her own, which began when she took her first ride at age 2.

Nir transports readers to the country's oldest ranch—Deep Hollow, in Montauk, New York, where settlers kept cattle as early as 1658, and where Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders set up a military base in the late 19th century—and Rosenberg, Texas, where postal worker Larry Callies is fighting the erasure of black horsemen from the American narrative at The Black Cowboy Museum. She explores the debate about whether the storied wild pony swim on Virginia’s Chincoteague Island, where “saltwater cowboys” have been driving the ponies across the Assateague Channel for nearly a century, harms the animals.

As she examines what the horse means to America and who, historically, has been able to claim these animals as their own, Nir interweaves her own uneasy relationship to the often- rarefied world of equestrian sport, as the daughter of an immigrant. “A lot of my relationship with this world was this tension of belonging and not belonging because of how wrapped up horses are with a very specific American identity, which is white, landed at Plymouth Rock,” she says.

Smithsonian spoke to Nir about misconceptions about America’s history of horses, the erasure of black cowboys and her own life with horses.

How did you determine which places and characters to include in the book?

My story as ‘horse crazy’ myself necessarily overlapped with a tremendous number of my peers, as I've been riding since I was 2. It’s unexpected, given that I'm a born-and-raised Manhattanite, and I'm riding in this urban setting, but horses are actually a part of New York City's identity. The avenues are the width of four horses [and wagons] abreast, and the streets are the width of two horses [and wagons] abreast. You don't think of that in this thoroughly modern metropolis, but it was a city built for and by horses. There are drinking fountains for horses scattered all over the city, still.

I hunted down horses in my city and I found them in a barn on 89th Street, which was a vertical stable in essentially a townhouse. The horses lived upstairs and trotted down the steps. I became a mounted parks enforcement officer auxiliary patrolling in Central Park on the bridle paths. And then I found this cowboy in the middle of the East River— Dr. Blair, the founder of the New York City Black Rodeo. All of these overlaps with horses and my young life ended up being this thread that I unspooled to find the history behind these horsemen and women.

What are some of our biggest blind spots or misconceptions when it comes to the history and culture of horses in America?

Our misconception is that there's such a thing as a wild horse—there's no such thing. Every horse in America, running ‘free’ is feral. They're like cats that live in a junkyard. Some 10,000 years ago, the horse was entirely wiped out from the American continent, and they were reintroduced by Spanish conquistadors to America in the 1490s. What's so fascinating is that we link a horse to America's soul. The truth is that Native Americans hadn't seen a horse before the 1490s, and Native American equestrian prowess is inked in buffalo hide [paintings]. That, to me, says, horses are whatever we make them to be. Horses are projections of our thoughts about ourselves.

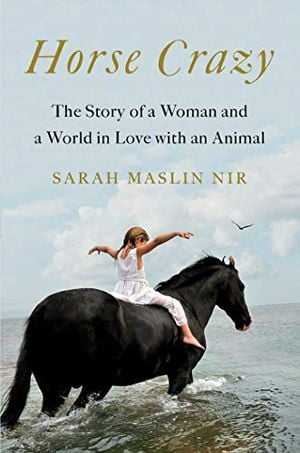

Horse Crazy: The Story of a Woman and a World in Love with an Animal

It may surprise you to learn that there are over seven million horses in America—even more than when they were the only means of transportation—and nearly two million horse owners. Horse Crazy is a fascinating, funny, and moving love letter to these graceful animals and the people who are obsessed with them.

What do you want people to know about black cowboys and other groups who have been written out of American equestrian history?

I feel a parallel in my own story with that. I'm the daughter of a Holocaust survivor. Hitler tried to erase my people, quite literally, from the world's story. So, in finding out and researching the omission of black cowboys from America's origin narratives, I felt that similar thread of injustice. The West was integrated. It was just frankly too hard of a place to have the same social strictures that existed on the other side of the Appalachian Mountains. Cowboys drank coffee from the same billycan, they sat around the same campfire. In a way, the West was more profoundly important to black cowboys than it was to white cowboys, because they could have a sense of freedom and equity in a way they couldn't elsewhere. History's written by the victors—the people who wrote the John Wayne movie scripts were white. And they wrote out people who shaped our country, just like the Germans tried to erase my people. I see a common thread in that. It felt very much in keeping with my mission as a journalist to, by telling the story, edge towards righting that wrong.

How are the national conversations that we’re having about race spilling into the horse world?

They're ricocheting around the hunter-jumper sport, which is show jumping, because it's almost entirely white. Why? Obviously in this country, wealth lines often fall along race lines because of systemic racial injustice. But that can't explain it all. That can't explain why this sport is almost exclusively white, with some very small but notable exceptions. And that conversation is really wracking the industry, but nobody's giving any answers. In other horse sports, it's not [the case]. In western riding, there's a big black rodeo scene. There's a lot of reckoning that has to happen from the show stables to the racing barns of this country.

What did you learn about America's relationship with horses today, and how it is different from the rest of the world?

I think in other countries horse sports are more democratic. In the U.K. for example, they are a countryside pastime, and not as bound up in the elite. Here, horses both symbolize our independence, as in cowboy culture, and in posh racing and show jumping, our class lines.

From racing being called “the Sport of Kings” to elite show jumping, these worlds seem out of reach for so many people, but the truth is that horses aren't exclusive. Horses demand one thing, which the great American horse whisperer Monty Roberts said to me: For you to be a safe place to be. They don't need cashmere and jodhpurs from Ralph Lauren. That's the stuff we impressed on them that they never asked for; horses are totally incognizant of wealth and splendor. I guess I realized that passion for them is so intrinsically linked with American identity, and it's so widespread, far beyond people who've ever even stroked a horse's nose. I hope that the book allows people to access horses, to understand them, because horses are democratic.

What was most surprising to you in reporting this book?

The depths people go to have horses in their lives. Like Francesca Kelly, the British socialite who smuggled horse semen [from India to America to revive a breed], to Larry Callies, who spent his life savings to stake a claim for him and his community in the horse world. The people who fly horses across the Atlantic—which I traveled with in the belly of a 747—to the town of Chincoteague, which fights for their tradition to continue. That fascinated me because that means there's something more to horses than horses, and that’s what I hope the book unpacks.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.