How Coffee, Chocolate and Tea Overturned a 1,500-Year-Old Medical Mindset

The humoral system dominated medicine since the Ancient Greeks—but it was no match for these New World beverages

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/91/8391baf8-f329-4cfb-9cd8-eaa2c72cebb9/fayjkf.jpg)

When Italian botanist Prospero Alpini traveled to Egypt in 1580, he discovered a world of unusual plants—strangely shaped bananas, bright red opium poppies, chunky baobab trees. After returning to Europe three years later, Alpini publicized his findings in two volumes, De Plantis Aegypti and Da Medicina Aegyptiorum. Among their illustrations and descriptions of the wondrous flora of the Middle East and North Africa were observations of a peculiar plant: the coffee bush.

This plant would not only find its way into daily rituals across Europe—it would upend a millennia-old medical mindset.

“The Arabians and Egyptians make a sort of decoction [hot brew] of it, which they drink instead of drinking wine; and it is sold in all their public houses, as wine is with us,” wrote Alpini, whose writings made him the first European to describe Egyptian medical treatments.

Alpini and other physicians swiftly began trying to describe the impact coffee had on health. But doctors struggled to understand the effects of coffee and two other newly imported beverages— chocolate and tea. All of these arrived around the same time in the mid-16th century. Chocolate was described by European travelers to South America; tea from those who traveled to China; and coffee came from North Africa, as Alpini described. As international commerce grew throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, demand for all three exploded.

These exotic beverages presented physicians of the day with a significant problem: How did they fit into the predominant medical theory of the time, the humors?

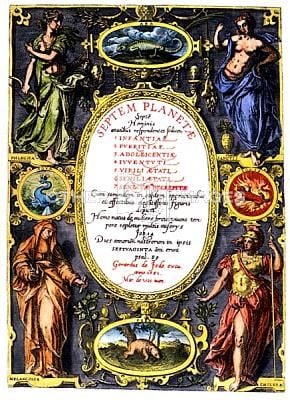

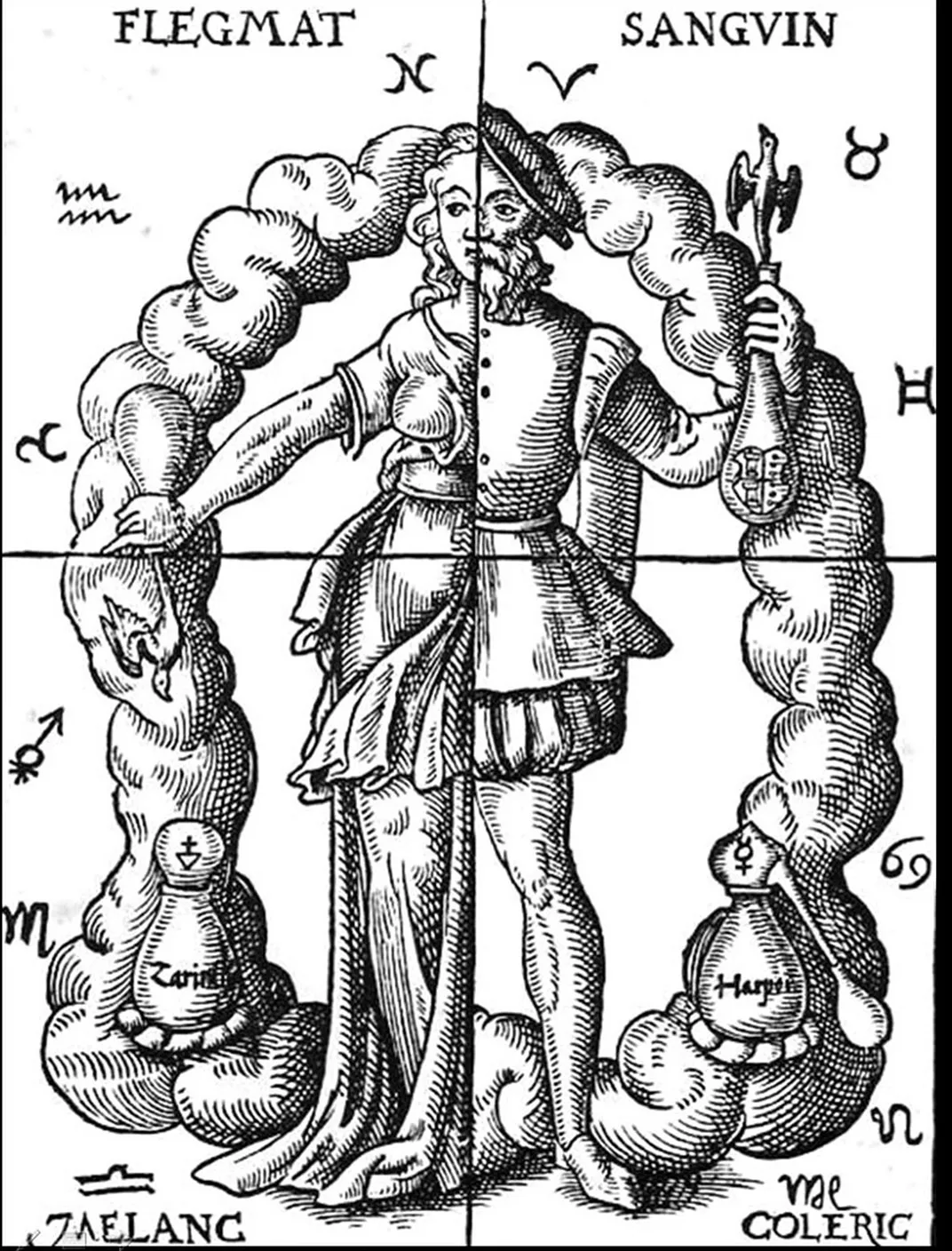

The concept of humors stretches back to Ancient Greece. Writers including Hippocrates and Galen believed the human body was composed of four humors, or fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. The key to this pseudo-medical system was balance. Every individual, the thinking went, had a unique humoral composition—and if their body fell out of equilibrium, illnesses befell them.

Medicine at the time, therefore, was intensely personal, writes David Gentilcore in Food and Healthy in Early Modern Europe: Diet, Medicine and Society. “Foods like cheese and wine might be converted into nourishing foods in some bodies,” he writes, “but could be poisons in others.”

According to Galen, the first way physicians would treat illness was with food; surgery and cauterizing were a last option. Every food had its own humoral affiliation, which changed slightly based on preparation (if it was cooked or spiced). Foods could be hot, cold, dry or moist, with each characteristic mapping onto the fluids of the body. Galen’s famous text On the Power of Foods classified foods based on their humoral powers, leaving a roadmap for future physicians. The book included recipes, “because Galen believed that a good doctor should also be a good cook,” writes translator and historian Mark Grant.

The way this worked in practice was that doctors would prescribe specific foods to adjust their patient’s humoral balance. So if someone displayed too much heat—a fever—they might receive a bloodletting treatment and be instructed to eat cold foods, like salad or vegetables. If a person experienced indigestion from eating too much, they could take a hot and dry prescription, like pepper and wine.

But as international trade expanded pantries and palates across Europe, physicians clashed over how to categorize ingredients that weren’t described in Galen’s work. “As you have more and more of these new things, by trying to fit them in, you explode the old system from the inside,” says Mary Lindemann, a professor of history at University of Miami and the author of Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe.

Sometimes physicians were more successful, particularly if the New World foods were similar enough to those already existing in Europe. Finding New World beans to be close enough to European beans, and turkeys to be not far off from familiar peacocks, Europeans assigned them the same humoral properties as their Old World counterparts.

But coffee, tea and especially chocolate proved more troublesome. All three were dietary chameleons, seeming to change in form and quality at will. “Some people say [chocolate] is fatty, therefore it’s hot and moist,” says Ken Albala, a professor of history at University of the Pacific and author of Eating Right in the Renaissance. “But other physicians say, if you don’t add sugar, it’s bitter and astringent, so it’s dry and good for phlegmatic disorders. How can something be both dry and moist or hot and cold?”

The same debates happened with coffee, Albala says. Some physicians viewed the drink as having a heating effect. Others claimed coffee cooled the body by drying up certain fluids (an early acknowledgement of coffee as a diuretic). All three drinks—chocolate was usually consumed as a beverage—were astringent, but if mixed with sugar, their flavor was richer and more pleasant. Were they medicinal in all their forms, or only some? The answer depended largely upon the physician.

The debate continued as coffee houses sprang up across Europe and chocolate became even more popular as a beverage. In 1687, Nicolas de Blegny, physician and pharmacist to France’s Louis XIV, wrote a book on the “correct” usage of coffee, tea and chocolate to cure illness. In it, he voiced his annoyance at physicians who classified the qualities of the beverages differently based on the diseases they wanted to treat.

If one substance could cure any illness, what did that say about the rest of humoral theory? As new medical paradigms began entering physicians’ diagnostic vocabulary in the 17th century, humoral theory began to fall apart. Some doctors now looked at the body as a series of mechanical parts, fitting together like a well-oiled machine. Others saw it in terms of its chemistry.

But tradition is a stubborn thing. For decades, plenty of doctors continued to draw on humors for their medical practice. “Doctors persisted in keeping the Galenic humoral system and resisted people who argued against it,” Lindemann says. “In mercenary terms, it’s a matter of people preserving their medical monopoly. It’s also probably a matter of conviction.”

In the 19th century, numerous discoveries struck the final blow to the humoral system. Physiology and anatomy advanced. Disciplines like pharmacology began investigating how drugs affected the body, and the discovery of microorganisms revolutionized how doctors viewed illness. With the invention of more powerful microscopes, they could hypothesize about how bacteria might disrupt a healthy body, destroying the notion that an imbalance of humors was the source of disease.

Humors may have died with modern medicine, but their legacy did not. Even today, they’re visible in aphorisms like “starve a fever, feed a cold” and in certain herbal remedies. As for the medicinal values of chocolate, coffee and tea—whether chocolate helps us lose weight, tea stimulates the metabolism, or coffee is healthful or harmful—we’re still arguing over that too.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)