How Col. Ellsworth’s Death Shocked the Union

It took the killing of their first officer to jolt the North into wholeheartedly supporting the Union cause

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1861-The-Civil-War-Awakening-631.jpg)

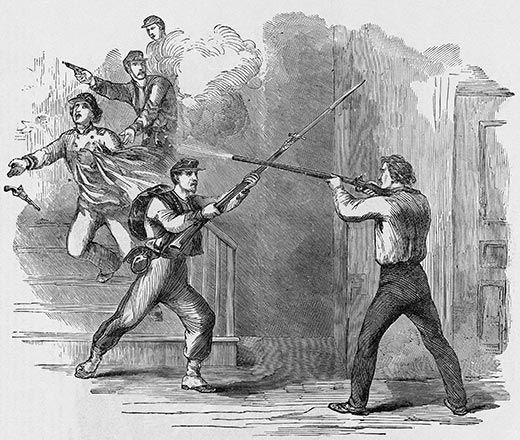

On May 23, 1861, Virginia seceded from the Union. President Abraham Lincoln ordered troops to occupy the port city of Alexandria. The next day, an enraged innkeeper there fired a shotgun point-blank into the chest of Col. Elmer Ellsworth of the 11th New York Volunteers. The innkeeper was immediately gunned down by one of Ellsworth’s men; the colonel became the first Union officer to die in the Civil War. In his new book, 1861: The Civil War Awakening, Adam Goodheart explains that Ellsworth was not merely a surrogate little brother to Lincoln, but also an exemplar of the romantic idealism that characterized the generation of Americans that came of age in the 1850s. Here is how Goodheart portrays the aftermath of Ellsworth’s death:

By the following evening, public gatherings in New York and other major cities offered grandiloquent testimonials and took up collections for the support of Ellsworth’s parents, left destitute by the death of their only child. Army recruiting offices were mobbed as they had not been since the first week of the war. At the beginning of May, Lincoln had asked for 42,000 more volunteers to supplement the militiamen called up in April. Within the four weeks after Ellsworth’s death, some five times that number would enlist.

A torrent of emotion, penned up during the anxious weeks since Sumter’s fall, had been released, pouring out for a dead hero who had never fought a battle, but was rather, as one newspaper put it, been “shot down like a dog.” There was more to the response than just 19th-century sentimentality, more than just patriotic fervor. Across America, Ellsworth’s death released a tide of hatred, of enmity and counter-enmity, of sectional bloodlust that had hitherto been dammed up, if only barely, amid the flag-waving and patriotic anthems.

Indeed, it was perhaps Ellsworth’s death, even more than the attack on Sumter, that made Northerners ready not just to take up arms, but to kill. For the first month of the war, some had assumed that the war would play out more or less as a show of force: Union troops would march across the South and the rebels would capitulate. Yankees talked big about sending Jeff Davis and other secessionist leaders to the gallows, but almost never about shooting enemy soldiers. They preferred to think of Southerners in the terms that Lincoln would use throughout the war: as estranged brethren, misled by a few demagogues, who needed to be brought back into the national fold. Many Confederates, however, had already expressed relish at the prospect of slaughtering their former countrymen. “Well, let them come, those minions of the North,” wrote one Virginian in a letter to the Richmond Dispatch on May 18. “We’ll meet them in a way they least expect; we will glut our carrion crows with their beastly carcasses.”

After the tragic morning in Alexandria, it suddenly dawned on the North that such talk had not been mere bluster. Newspapers dwelt on every lurid detail of the awful death scene—especially the “pool of blood clot, I should think three feet in diameter and an inch and one half deep at the center,” as one correspondent described it. On the Southern side, editorialists rejoiced, boasting that Ellsworth would be only the first dead Yankee of thousands. “Down with the tyrants!” proclaimed the Richmond Whig. “Let their accursed blood manure our fields.”

Although the Union rhetoric would never quite reach such levels, many in the North now began demanding blood for blood. Ellsworth’s troops, Lincoln’s secretary John Hay wrote with solemn approbation, had pledged to avenge Ellsworth’s death with many more: “They have sworn, with the grim earnestness that never trifles, to have a life for every hair of the dead colonel’s head. But even that will not repay.”

In Washington, Ellsworth’s body was brought to lie in state in the East Room of the White House, his chest heaped with white lilies. On the second morning after his death, long lines of mourners, many in uniform, filed through to pay their respects; so many thronged into the Presidential Mansion that the funeral was delayed for hours. In the afternoon, the cortege finally moved down Pennsylvania Avenue, between rows of American flags bound in swaths of black crape, toward the depot where Ellsworth’s men had disembarked a few weeks earlier. Rank after rank of infantry and cavalry preceded the hearse, which was drawn by four white horses, and followed by Ellsworth’s own riderless mount, and more troops, and then a carriage with the president and members of his cabinet.

Even after Ellsworth’s body had, at last, been laid to rest on a hillside behind his boyhood home in Mechanicsville, New York, the nationwide fervor scarcely waned. Photographs, lithographs and pocket-size biographies paying tribute to the fallen hero poured forth by the tens of thousands. Music shops sold scores for such tunes as “Col. Ellsworth’s Funeral March,” “Ellsworth’s Requiem” and “Col. Ellsworth Gallopade.”

Ellsworth’s death was different from all those to follow over the next four years: like Atlantic Monthly reporter Nathaniel Hawthorne, most Northern writers referred to it as a “murder” or “assassination,” an act not of war but of individual malice and shocking brutality. By the time Hawthorne’s article appeared, however, many other American places had been soaked in blood. As the war’s inexorable toll rose, touching almost every family throughout the nation, Americans would lose their taste for collective mourning. Death became so commonplace that the demise of any one soldier, whether a gallant recruit or battle-scarred hero, was drowned in the larger grief. Not until the war’s final month–when another body would lie in state in the East Room, and another black-draped train make its slow way north–would Americans again shed common tears for a single martyr.

Ellsworth’s memory never faded among those who knew him well. Lincoln’s secretary John Nicolay, who lived to see the 20th century, wrote in his sweeping history of the war that the response to Ellsworth’s death “opened an unlooked-for depth of individual hatred, into which the political animosities of years . . . had finally ripened.”

As for Lincoln, his young friend’s death affected him like no other soldier’s in the four years that followed. On the morning that the news reached the president, Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts and a companion—not yet aware of Ellsworth’s death—called at the White House on a matter of urgent business. They found Lincoln standing alone beside a window in the library, looking out toward the Potomac. He seemed unaware of the visitors’ presence until they were standing close behind him. Lincoln turned away from the window and extended his hand. “Excuse me,” he said. “I cannot talk.” Then suddenly, to the men’s astonishment, the president burst into tears. Burying his face in a handkerchief, he walked up and down the room for some moments before at last finding his voice: “I will make no apology, gentlemen,” said the president, “for my weakness; but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in great regard.”

Almost alone among the millions of mourners, perhaps, Lincoln understood that Ellsworth’s death had not been glorious. Others might talk of his gallantry, might hail him as a modern knight cut down in the flower of youth. But for the president, preparing to send armies of Americans into battle against their Southern brothers, the double homicide in a cheap hotel represented something else: the squalid brutality of civil war.

Excerpt adapted from 1861: The Civil War Awakening by Adam Goodheart, to be published by Knopf on April 15, 2011