By December 1919, Edith Wilson had finally settled into a routine. After weeks of increasingly frail health, her husband, President Woodrow Wilson, had suffered a massive stroke on October 2. The rest of the month was a white-knuckled horror show as Woodrow’s health lurched from crisis to crisis. He would seem to be recovering strength, only to be thrown back by a fever or infection. When each day dawned, the first lady wondered if it would be her husband’s last.

November brought its own terrors. The president’s life no longer hung in the balance, but he was far from healthy. Meanwhile, debate raged over the Treaty of Versailles and the inclusion of Woodrow’s beloved League of Nations. Even close friends were telling Edith the president was killing his own project by insisting the Senate ratify the treaty with no changes or amendments. Her husband continued to swear amendments were impossible, even immoral, and if she urged him to compromise she was betraying his principles. By a healthy margin of 38 to 53, the Senate voted the treaty down on November 19, but its supporters vowed to fight another day.

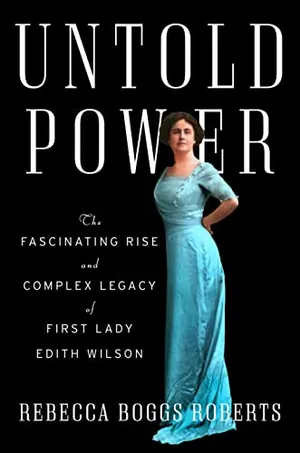

Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson

A nuanced portrait of the first acting woman president, written with fresh and cinematic verve by a leading historian on women’s suffrage and power

Now it was December. Chilly but sunny, Washington had yet to see a real snowfall. The president remained seriously ill. Virtually no one was allowed to see him. Edith met all inquiries with the same polite but firm brush-off: The president was mentally as sharp as ever; he was merely suffering from nervous exhaustion. He was not accepting meetings, but she would be happy to relay any important messages and return any necessary replies. This seemed to satisfy the bulk of would-be visitors. Most of them were content to conduct their business in writing, usually addressed directly to her.

Conspiring with the president’s doctor, Cary Grayson, and secretary, Joe Tumulty, Edith had begun to think she just might be able to manage this state of affairs for as long as she must. But then the cracks in the scheme began to appear, starting with blowback from Secretary of State Robert Lansing, never Woodrow’s biggest fan in the cabinet, who found the silence from the White House infuriating.

Long before the stroke, Lansing had realized his position was impossible. He disagreed with the president over the urgency of going to war, how the war was conducted, and the tactics and specifics of the peace process. He did not believe his counsel in these matters had been given the respect he was due. In fact, he and his boss disagreed so often, the president had seriously considered firing him in September. Before he could act on that impulse, Woodrow had collapsed in his train car.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/62/30/6230ab03-8563-4aa3-b606-8d7fcde2432b/woodrow_and_edith_wilson2_courtesy_copy.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7d/e8/7de8a31b-2bce-4c84-a84a-26a86644c6e5/edith_and_wood.png)

Lansing did not trust the Wilson White House to tell the truth about the president’s health. He suspected the situation was much more dire than the public was being led to believe. Stuck in a job he hated with a boss who wouldn’t or couldn’t act, Lansing was not alone in his frustration. Several Republican members of the Senate were also deeply suspicious. The most vocal and colorful member of this faction was Albert B. Fall of New Mexico. With his walrus mustache and ten-gallon hat, Fall would go on to earn the distinction of being the first cabinet secretary ever sentenced to jail, convicted in 1929 of taking bribes in the infamous Teapot Dome scandal.

Fall had lately taken to yelling to everyone who would listen that Woodrow was not capable of serving as president. He had even shouted on the Senate floor, “We have [a] petticoat government. Wilson is not acting. Mrs. Wilson is president.” For the most part, people ignored him. But the one thing Fall hated more than the Wilson administration was the Carranza government in Mexico, which had thwarted the United States’ petroleum interests for years. Then, in December 1919, an American consular agent named William Jenkins was kidnapped in the Mexican city of Puebla. And Fall was handed the perfect opportunity to kill two birds with one stone.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2d/11/2d11000a-1ac1-4c0b-8cc0-451c854afda0/robert_lansing_cph3b47713_3x4a.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/25/6025ddf0-7990-4a9e-880a-ae5b52c3f0e3/fall.png)

Lansing, no longer deferring to Woodrow on matters of foreign policy, sent a strongly worded letter to Mexico demanding Jenkins’ release. It stopped just short of threatening war. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee, knowing the peace-seeking president could not have approved such belligerent tactics, asked Lansing if he had consulted with his chief executive. With visible anger, Lansing replied that no, he had not consulted with the president at all since September. As far as Lansing knew, not a single member of the cabinet had met with the president about anything in months.

That was all the justification Fall needed. He introduced a resolution appointing a delegation of the Senate committee to visit the president to hear his views on the Mexican situation. He graciously volunteered to go himself. The Democrats on the committee chose Gilbert Hitchcock of Nebraska, a very reluctant recruit to this enterprise. Hitchcock, like literally everyone else, knew this was not actually a visit about the Jenkins kidnapping. It was a reconnaissance mission.

And so the stage was set for a showdown.

Fall cornered Wilson’s secretary, Tumulty, in the Capitol and demanded an immediate meeting with the president, playing up the urgency of helping an American in foreign custody. Tumulty, who knew Fall’s vehemence had very little to do with Mexico, decided to go all in, agreeing to a meeting that very day, December 5, at 2:30 in the afternoon. Fall, counting on the usual stonewalling, was surprised by Tumulty’s helpfulness and grew suspicious. He even suggested the meeting could wait a couple of days. But this had now become a high-stakes game of chicken, and Tumulty would not be the first to flinch. He insisted a timely meeting was just what everyone wanted. Fall agreed and helpfully alerted the entire Washington press corps.

Tumulty ran back to the White House and warned Edith and Grayson that a Senate delegation was on the way. Everyone involved later described the day in theatrical terms; they knew they were putting on a show.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/32/c432b701-ad72-46f9-bd4b-3e463defdba0/1920px-pres__mrs_wilson_lccn2016827619.jpg)

Tumulty called in Robert Woolley, head of publicity for the Democratic Party, to help stage a “dress rehearsal.” Together, Tumulty, Woolley, Grayson and Edith surveyed the props and cast they had available. Woodrow, who by necessity would star in this little production, had good days and bad days. His entire left side was still paralyzed. He tired easily, and sometimes his speech slurred. In his weakness and exhaustion, he could find it hard to concentrate on a conversation, and Edith would have to gently prod him to respond. But he also had windows of clarity and wit. Maybe today would be one of those days?

The team decided Edith would stay in the room during the senators’ meeting. Between her and the sympathetic Hitchcock, perhaps they could keep the mood light and the conversation flowing. The patient-slash-leading man knew exactly what was going on. He dubbed Fall’s visit a “smelling committee” and comprehended just how high the stakes were. But all he could do was rest up for his moment in the spotlight and let his team get on with preparations.

First, the group had to figure out where to set the stage. The president spent most of his day in bed. Edith had once tried to prop him up in a wheelchair, but he had listed to the side alarmingly. White House usher Ike Hoover had finally come up with the genius idea of renting a rolling beach chair from a vendor in Atlantic City. It was somewhat more stable, but the whole apparatus was a little clownish and not very presidential.

The production team decided the president would have to receive the senators lying down in bed, with only his head elevated. Edith covered his left side with a blanket, tucked up under his chin. Tumulty placed a copy of the Senate report on Mexico on a table within easy reach of his good right hand. Grayson placed chairs for the senators that would limit their view of the president’s left side and made sure the seats were well lit, while the bed remained in shadow. As Hoover recalled, “It was quite impossible for one coming from a well-lighted part of the house to see anything to satisfaction.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dc/12/dc12f046-96bb-487a-a0ea-783c37a1dbe6/1280px-wilson_and_tumulty_4322929472_cropped.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2e/b2/2eb250bc-84c7-424d-ba54-cf065c4cac11/wilson.png)

Stage manager Edith surveyed her star, realizing her costuming options were limited. He had worn a formal silk dressing gown to briefly greet the king of Belgium, but it bunched up uncomfortably in bed, and Woodrow much preferred a beloved old brown sweater. It was a little moth-eaten, but the interests of ease and comfort outweighed formality here, so the sweater went on. With no visitors, Edith hadn’t insisted on the president being shaved regularly, and now a white wispy beard on his gaunt gray face did nothing to boost the illusion of vitality. The president submitted to a shave. It was all they could do. As 2:30 approached, everyone took their places, crossed their fingers and hoped for the best.

Fall and Hitchcock arrived at the White House right on time, trailed by more than 100 reporters. It was the first time Edith had allowed press at the White House since the stroke, which of course triggered pandemonium as well as some skepticism. As the New York Times dryly put it, “There was apparently an effort to have it appear that those around the president wanted the fullest publicity.” The journalists all knew the real reason for this meeting and stood by ready to publicize every detail Fall provided on Woodrow’s condition. While the reporters waited downstairs, the senators were escorted up to the president’s bedroom. As rehearsed, Grayson met the pair at the door. Fall asked if the meeting had a time limit. Grayson, keeping up the pretense that this visit was wholly welcome, answered, “No, not within reason, senator.”

Then he opened the door.

Edith tried not to let her loathing for Fall show. She gripped a pencil in one hand and a notebook in the other so she could avoid shaking his hand. Then she watched helplessly as Fall entered the room and approached the president’s bed.

Woodrow astonished everyone by greeting Fall with a firm handshake and waving him casually to the chair that was staged for him. Hitchcock followed timidly behind. As Edith recounted in her memoir, Fall, not sure what to make of this scene, ventured a tepid “Well, Mr. President, we have all been praying for you.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/2b/652bd85b-2406-47cb-b4a7-e9b7b7b16716/woodrow_wilson_loc_npcc05361.jpg)

The president, without missing a beat, replied, “Which way, senator?”

As Fall laughed, Edith breathed a sigh of relief and began taking notes. “If agreeable, I wish Mrs. Wilson to remain,” said the president, as if her presence were expected.

“You seem very much engaged,” Fall commented to Edith.

“I thought it wise to record this interview so there may be no misunderstandings or misstatements made,” Edith shot back.

Fall asked if the president had even seen the Foreign Relations Committee report on Mexico. Just as rehearsed, Woodrow grabbed the report off his bedside table with his good right hand. “I have a copy right here,” he crowed, waving it triumphantly.

And so the meeting proceeded. Woodrow was charming. Fall was thwarted. Edith fumed. Hitchcock smiled and nodded with utter terror in his eyes. Grayson hovered in the doorway, cautiously optimistic. The meeting was going so well that when he was called away to the telephone, he felt confident leaving the drama to play out.

Fall, disappointed he hadn’t caught the president drooling or incoherent, turned his focus to the ostensible reason for the meeting. He attempted to play up the Jenkins kidnapping and urge Woodrow to take stronger action against Mexico. But then, in a piece of stagecraft even this play’s planners could not have foreseen, Grayson returned from his phone to call to announce that Jenkins had just been released. Grayson felt, the Times later reported, “like an actor making a sensational entrance.” Fall had no choice but to wrap the meeting up. Woodrow spoke of getting on his feet again soon and wished his visitors well.

Almost giddy with relief, Grayson escorted Fall and Hitchcock downstairs to face the waiting reporters. They didn’t even pretend to ask about Mexico, instead peppering both senators with questions about the president’s condition.

Hitchcock led off, describing the president’s mental alertness, his healthy color and even his old brown sweater in glowing terms. Fall was forced to agree, saying Woodrow “seemed to me to be in excellent trim, both mentally and physically.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/96/8596069e-b16f-411b-825e-35b7732182ec/edith_bolling_galt_wilson_full-length_portrait_standing_facing_front_hands_behind_waist_lccn93516290.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/65/ce65d7a7-cc4f-41a6-badf-2474d44aeda5/painting_of_edith.png)

The resulting news coverage was everything Edith and her confidants could have wished for. The New York Times was typical, stating, “The two senators who interviewed the president with the ill-concealed purpose … to ascertain the truth or falsity of the many rumors that he was in no physical or mental condition to attend to important public business, came away from the White House convinced that his mind was vigorous and active.” The president acted his part so well, the senators even gave him more credit than he was due. As Edith gushed in her memoir, Fall “assured the reporters that the president was mentally fit … and that he had the use of the left as well as his right side, which, of course, was an overstatement of the case, for Mr. Wilson’s left side was nearly useless.”

Although Woodrow’s critics continued to demand less secrecy from the White House, the immediate rumors of his condition had been publicly, triumphantly quashed. For the moment, everyone believed the president was running the country.

Edith just had to make sure everyone kept believing it until it was true, or until the 1920 election—whichever came first.

Excerpted from Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson by Rebecca Boggs Roberts, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Rebecca Boggs Roberts.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5b/91/5b9144f0-6e06-4dcc-8378-5be5933a9802/edith.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rebecca2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rebecca2.png)