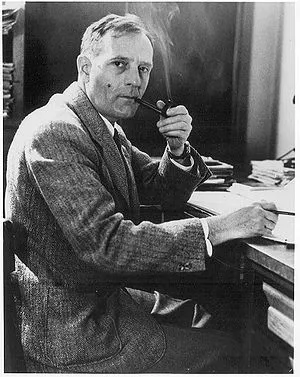

How Edwin Hubble Became the 20th Century’s Greatest Astronomer

The young scientist demolished the old guard’s ideas on the nature and size of the universe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Past-Imperfect-Hubble-631.jpg)

When the great minds of science gathered at the U.S. National Museum (now known as the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History) on April 26, 1920, the universe was at stake. Or at least the size of it, anyway. In scientific circles, it was known as the Great Debate, and although they didn’t know it at the time, the astronomy giants Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis—the two men who came to Washington, D.C., to present their theories—were about to have their life’s work eclipsed by Edwin Hubble, a young man who would soon become known as the greatest astronomer since Galileo Galilei.

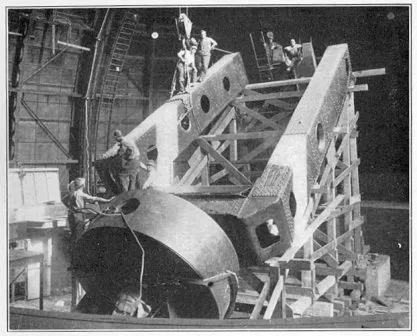

Harlow Shapley arrived from the Mount Wilson Observatory, near Pasadena, home of the world’s most powerful observational device—the 100-inch Hooker Telescope. A Californian who had studied at Princeton, Shapley came to the Great Debate to advance his belief that all observable spiral nebulae (now recognized as galaxies) were simply distant gas clouds—and contained within one great galaxy, the Milky Way.

On the other hand, Curtis, a researcher at the Lick Observatory near San Jose and then director of the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh, believed that the spiral nebulae existed far outside the Milky Way. In fact, he referred to them as “island universes,” and he estimated that they were much like the Milky Way in size and shape.

After presenting their respective ideas to each other in advance, the two astronomers entered the auditorium that evening and engaged in a lively, formal debate over “The Scale of the Universe.” In essence, they disagreed on “at least 14 astronomical issues,” with Curtis arguing that the sun was at the center of what he believed was a relatively small Milky Way galaxy in a sea of galaxies. Shapley maintained his position that the universe comprised one galaxy, the Milky Way, but that it was much larger than Curtis or anyone else had supposed, and that the sun was not near its center.

Each man believed his argument had carried the day. While there was no doubt that Curtis was the more experienced and dynamic lecturer, the Harvard College Observatory would soon hire Shapley as its new director, replacing the recently deceased Edward Charles Pickering. Both men, it would turn out, had gotten their theories correct—partially.

Back in California, a 30-year-old research astronomer, Edwin Hubble, had recently taken a staff position at the Mount Wilson Observatory, where he worked beside Shapley. Hubble was born in Missouri in 1889, the son of an insurance agent, but at the end of the century his family moved to Chicago, where he studied at the University of Chicago. A star in several sports, Hubble won a Rhodes scholarship and studied at Oxford. Though he promised his father he’d become a lawyer, he returned to Indiana to teach high school Spanish and physics (and coach basketball). But he remained fascinated by astronomy, and when his father died, in 1913, the young scholar decided to pursue a doctorate in the study of stars at the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory.

He completed his dissertation (“Photographic Investigations of Faint Nebulae) and received his PhD in 1917, shortly before enlisting in the U.S. Army during World War I. It would be said that while he was in France, he taught soldiers to march at night, navigating by the stars. When he returned to the United States, Hubble was hired by George Ellery Hale, the director of the Mount Wilson Observatory, where he set about observing and photographing stars that were thought to be located in the Andromeda nebula within the Milky Way.

In October 1923, Hubble was examining photographs he had taken of the Andromeda nebula with the Hooker Telescope when he realized that he might have identified a Cepheid variable—an extremely luminous star. Hubble thought he might be able, over time, to calculate its brightness. And in doing so, he might accurately measure its distance.

For months, Hubble focused on the star he labeled “VAR!” on the now-famous photograph. He could determine by the star’s varying, intrinsic brightness that it was 7,000 times brighter than the sun, and according to his calculations, it would have to be 900,000 light-years away. Such a distance obliterated even Shapley’s theory on the size of the universe, which he estimated at 300,000 light-years in diameter. (Curtis believed it was ten times smaller than that.)

The implications of a star nearly a million light-years away were obvious, yet Shapley quickly dismissed his former colleague’s work as “junk science.” But Hubble continued to photograph hundreds of nebulae, demonstrating a method of classifying them by shape, light and distance, which he later presented to the International Astronomical Union.

In essence, he was credited with being the first astronomer to show that the nebulae he had observed were neither gas clouds nor distant stars in the Milky Way. He demonstrated that they were galaxies, and that there were countless numbers of them beyond the Milky Way.

Hubble wrote Shapley a letter and presented his findings in detail. After reading it, Shapley turned to a graduate student and delivered the remark for which he would become famous: “Here is the letter that has destroyed my universe.”

Edwin Hubble would continue measuring the distance and velocity of objects in deep space, and in 1929, he published his findings, which led to “Hubble’s Law” and the widely accepted realization that the universe is expanding. Albert Einstein, in his theory of general relativity, produced equations that showed that the universe was either expanding or contracting, yet he second-guessed those conclusions and amended them to match the widely accepted scientific thinking of the time—that of a stationary universe. (He later called the decision to amend the equation “the biggest blunder” of his life.) Einstein ultimately paid a visit to Hubble and thanked him for the support his findings at Mount Wilson gave to his relativity theory.

Edwin Hubble continued to work at the Mount Wilson Observatory right up until he died of a blood clot in his brain in 1953. He was 63. Forty years later, NASA paid tribute to the astronomer by naming the Hubble Space Telescope in his honor, which has produced countless images of distant galaxies in an expanding universe, just as he had discovered.

Sources

Articles: “Star that Changed the Universe Shines in Hubble Photo,” by Clara Moskowitz, Space.com, May 23, 2011, http://www.space.com/11761-historic-star-variable-hubble-telescope-photo-aas218.html. “The 1920 Shapley-Curtis Discussion: Background, Issues, and Aftermath,” by Virginia Trimble, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, v. 107, December, 1995. http://adsbit.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-iarticle_query?1995PASP%2E%2E107%2E1133T “The ‘Great Debate’: What Really Happened,” by Michael A. Hoskin, Journal for the History of Astronomy, 7, 169-182, 1976, http://apod.nasa.gov/diamond_jubilee/1920/cs_real.html “The Great Debate: Obituary of Harlow Shapley,” by Z. Kopal, Nature, Vol. 240, 1972, http://apod.nasa.gov/diamond_jubilee/1920/shapley_obit.html. “Why the ‘Great Debate’ Was Important,” http://apod.nasa.gov/diamond_jubilee/1920/cs_why.html. “1929: Edwin Hubble Discovers the Universe is Expanding,” Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science, http://cosmology.carnegiescience.edu/timeline/1929. “The Great Debate Over the Size of the Universe,” Ideas of Cosmology, http://www.aip.org/history/cosmology/ideas/great-debate.htm.

Books: Marianne J. Dyson, Space and Astronomy: Decade by Decade, Facts on File, 2007. Chris Impey, How it Began: A Time-Traveler’s Guide to the Universe, W. W. Norton & Company, 2012.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)