How Historic Preservation Shaped the Early United States

A new book details how the young nation regarded its recent and more ancient pasts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/91/2691c4f8-8ff6-4fbc-ba10-70631315b4ad/hancock-preservation-thumb3.jpg)

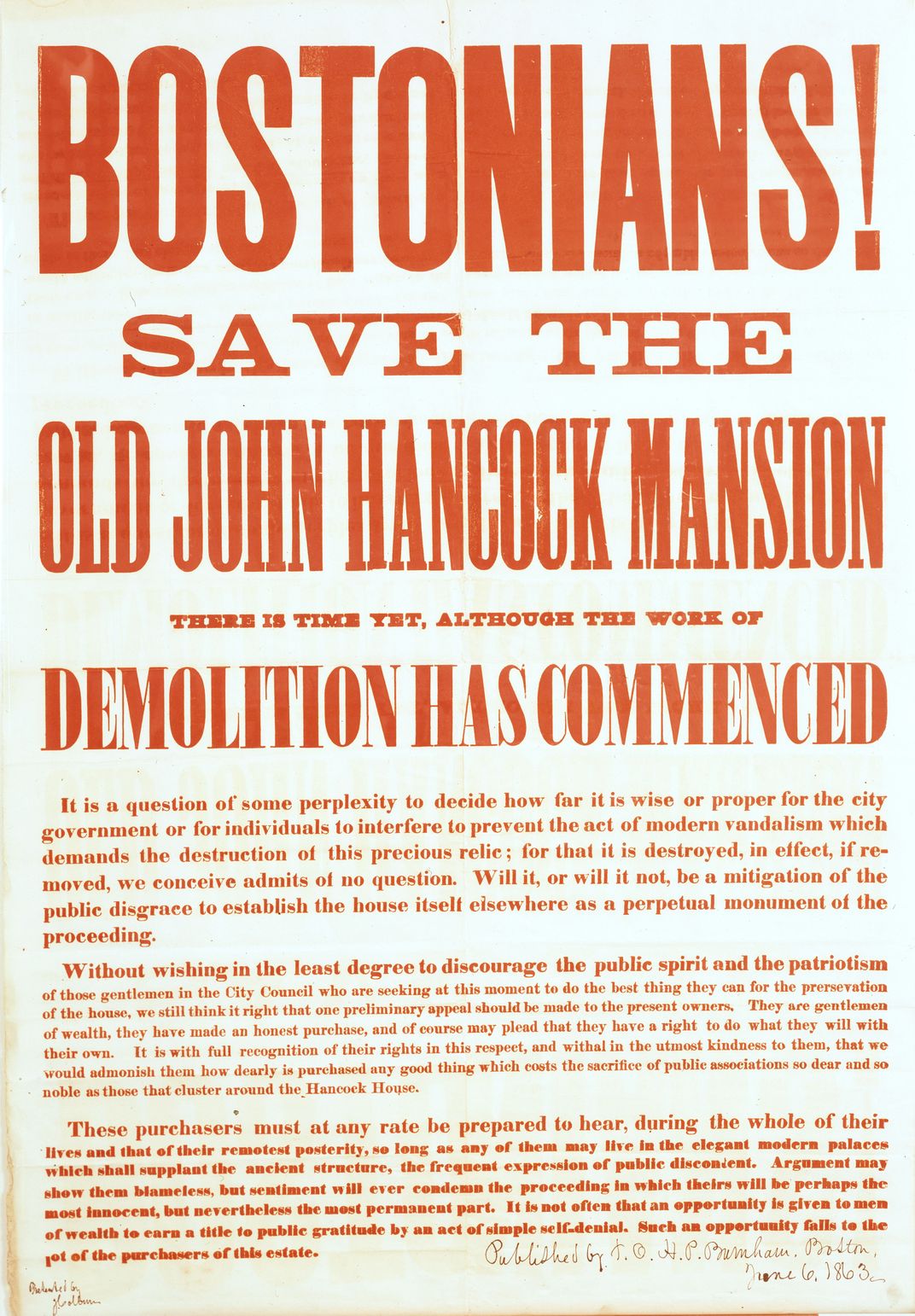

In the middle of the 19th century, the homes of two founding fathers, John Hancock and George Washington, were in danger of being torn down. For the Massachusetts patriot with the famous signature, it was his house just off of Boston Common in the city’s urban center. For the nation’s first president, it was his rural Virginia estate, Mount Vernon.

The press covered the potential destruction of the two sites with horror, and according to historian Whitney Martinko, the divergent fates of these homes encapsulates the history of historic preservation in the United States. While the Mount Vernon Ladies Association raised funds to purchase the president’s mansion from his nephew, and continue to own and operate the property today, Hancock’s home was sold and torn down to construct new residences.

“What did it mean about the United States if its citizens were most interested in how much money they could garner from developing any land available?,” asks Martinko. Her new book, Historic Real Estate: Market Morality and the Politics of Preservation in the Early United States, examines this question, among many others, in a fascinating exploration of how Americans grappled with preserving their past (or not) amid economic booms and busts. From its earliest years as a nation, the country’s government and its citizens battled over the costs and benefits of historic preservation, at times grounded in surprisingly progressive beliefs about whose history deserved to be protected.

Martinko spoke with Smithsonian about the themes of her book and the history of historic preservation in the United Sates.

Historic Real Estate: Market Morality and the Politics of Preservation in the Early United States (Early American Studies)

In Historic Real Estate, Whitney Martinko shows how Americans in the fledgling United States pointed to evidence of the past in the world around them and debated whether, and how, to preserve historic structures as permanent features of the new nation's landscape.

Let’s start with the most obvious question—what exactly is historic preservation?

Historic preservation is the practice of thinking through how to manage historic resources, and can include things like cemeteries, whole neighborhoods, farms or infrastructure. It encompasses the creation of places like historic house museums that are open to the public, but it also includes places like private homes for individuals who want to keep the historic character of their residence, or business owners who might want to inhabit a historic building, but want to also make use of it through adaptive reuse.

It could be as simple as doing some research into the history of a house by looking at things like census records, old deeds and also looking at maybe physical clues of the house’s past. So you might chip away paint layers on your walls and say, "Oh we found some old paint. We want to try to keep that original character intact."

On the local level, historic preservation might also involve writing a nomination for the local historic register. For instance, I live in Philadelphia; there's a local register of historic places that is managed by the city’s historical commission. And those exist all over the United States.

What makes the history of “preservation” so compelling?

We might think historic preservation is about stopping time, freezing something in the past. But in fact, historic preservation today, as well as in the past, has always been about managing change. In the first half of the 19th century, people in the early United States were focused on the future and about managing change in a modern nation.

The history of historic preservation also helps us appreciate what has been preserved. Independence Hall has been preserved, Mount Vernon, and a lot of our national iconic sites, as well as local sites—we should understand them in the context of what was demolished. Preserved historic sites are the result of choices that were made continually to keep these buildings in place.

Looking at the history of historic preservation helps us to see how people made these decisions, and how those decisions reflected debates about broader social and economic values.

What were those values for Americans in the first decades of the United States, between the Revolution and the Civil War?

The residents of the early nation tried to work out a very practical, tangible solution to a central issue that they faced then and that we face today: the relationship between pursuing private profit versus the public good.

This question took on new importance to people living through the Revolutionary Era, because that project of nation building sparked debates about what would be the guiding values of the United States. Some argued that preserving historic structures was a public good, others that private economic gain—which might mean demolition—was also in the public interest. This debate continues to shape preservation and larger discussions about private versus public interests today.

Who gets to decide what is preserved?

Historic sites are really interesting because they became a flashpoint. The property owner might want to do one thing, and maybe other citizens in the community wanted to do another, and they’re making claims that this church, or this historic house, or this cemetery really belonged to the entire community. Or that the site carried historic significance for people beyond the property owner. And so these are the debates that I'm really interested in my book. Preservation forced people to make decisions about what private ownership really looked like and whose voices mattered when considering the fate of sites that people thought were historic.

What is it about preservation in the early United States that's different and important?

The usual history of historic preservation in America often starts with the founding of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association in the 1850s, a moment in the United States we might have called the birth of preservation. The Colonial Revival comes after this, later in the 19th century and early-20th century, where there's interest in either preserving sites from colonial history or making replicas of colonial era objects and homes. The unsuccessful fight to save Penn Station in New York in the early 1960s is also a moment people look to as an important grassroots effort. And of course, federal legislation in the 1960s, the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 set up the National Register of Historic Places.

But the era before 1850 has been overlooked in the context of historic preservation. Many people living in the new nation were engaging in debates over how to keep historic sites. Americans were trying to find tangible solutions to defining the economic and social values of the early United States. Can corporations serve the public good? Or are they only a vehicle for the private interest? A lot of historic churches and city sites were owned by corporations, so Americans saw the fate of these sites as an answer to these larger questions. Early Americans debated the preservation of historic structures to answer similar questions about the nature of commercial profits and real estate speculation.

John Hancock’s house in Boston and George Washington’s estate at Mount Vernon raised these issues. While one was in the heart of Boston and one was along the Potomac in rural Virginia, in both cases, real estate developers were interested in them as investments, which made people really upset. One rumor was that John Washington, the nephew of George Washington, was going turn Mount Vernon into a hotel or even a factory site. A similar reaction arose in Boston when developers bought Hancock’s house as a teardown to put in new homes. People wondered how someone could conceive of these properties as anything but sacred sites, that should be valued as monuments to the great men who lived in them. And others understood their value as commercial real estate.

The Mount Vernon Ladies Association formed and purchased George Washington’s home, and has preserved it to this day. But in 1863 John Hancock's house met a different fate; it became the site of new townhouses.

How did the drive for historic preservation mesh with the drive for Westward Expansion?

In the 1780s, a number of men moved from Massachusetts into the Ohio Valley and planned the town of what became Marietta, Ohio. They decided that they want to legislate the preservation of what they called Monuments of Antiquity, indigenous earthworks built in the Ohio River Valley. They saw these as elements of the built environment and ed them evidence of what they would call human civilization, or in this case, American civilization.

Architecture is one of the ways that early Americans thought about the development of history. They thought that you could chart the rise of civilization, in their words, by looking at the material products of particular people at different times. So they saw earthworks as evidence of those who came before them--what they called ancient America.

Similarly, they saw colonial mansions built in the 17th century or early 18th century as evidence of the state of society in the colonial era and buildings constructed in the 19th century in the early U.S. as evidence of the state of society in the early United States. So rather than turning away from a colonial or indigenous past, residents of the early United States really embraced these older structures as evidence of what they would consider to be the progressive development of American civilization. And the United States was only the next step in that advancement.

Did Native Americans have a role in their own version of preservation?

Many residents of the early United States celebrated their idea of indigenous people in the past while denying living communities a place in the United States. U.S. migrants to the Ohio River Valley celebrated and preserved what they saw as ancient abandoned architecture while killing and removing Indigenous residents of the same region.

A more complex case of Native Americans involved in debates over preservation, as opposed to being the objects of preservation, was that of Thomas Commuck, a Narrangasset man. Commuck had inherited a family farm near Charlestown, Rhode Island, that he wanted to sell to support his move from the Brothertown nation, then in New York State, to Wisconsin. The state of Rhode Island was supposed to be holding Narragansett lands in trust for the community, but was also trying to sell off parcels as private property, so they allowed Commuck to do so, too.

But at the same time, other Narragansetts stayed in Rhode Island and were trying to keep their homes, their language, and their communities in place.

What we see is really two different strategies among the Narrangansett for trying to maintain family and survive in the new United States. Thomas Commuck was trying to earn cash to start a new home in the West even as other Narragansetts were trying to preserve their homes in Rhode Island. The difference was that the people in power, the citizens of the state of Rhode Island, would not have recognized what the Narragansetts near Charlestown, Rhode Island, were doing as valuable preservation of the American past.

How did other marginalized communities participate in debates about historic preservation?

This is an area that really needs more research. One example I found is Peyton Stewart, a free African American living in Boston in the 1830s. He lived in and operated a secondhand clothing shop out of Benjamin Franklin's childhood home in Boston. We know he took an interest in the home’s historic features only because he talked with Edmund Quincy, the wealthy white abolitionist and son of Boston’s mayor, about it, and Quincy recorded that conversation in his diary. At one point, Stewart invited Quincy in to assess the home’s historic character and asked Quincy whether he should buy the building.

This shows that Stewart was making enough money to consider purchasing property in Boston, and then he strategically asked a prominent abolitionist and antiquarian for his opinion about the house. Stewart was able to get the attention of a local, prominent Bostonian and build a relationship with him to show that he was, in Quincy’s terms, a "respectable citizen” because he was interested in preserving Boston’s past.

This case shows the sparsity of evidence of voices like Stewart’s and the challenges of finding out about buildings that were not preserved. Despite Stewart’s and Quincy’s interest in the building, Benjamin Franklin's childhood home was eventually destroyed in the 1850s.

What surprised you during your research?

My real surprise was the wide variety of sites that gained attention. Many of these extraordinarily decrepit buildings were not beautiful and were a real contrast to what was considered as providing good living standards. I was also surprised by the national debate that erupted over Ashland, the home of Kentucky politician Henry Clay. When one of his sons, James B. Clay, bought Ashland from his father's estate and announced in the newspapers that he was going to preserve his father's home, everyone was very excited.

And then he leveled the house to the ground. A great uproar occurred. And then he said, "No, no, I'm preserving my father's home. I'm building a new and better house on the same foundation." And so this elicited a great debate about what “preservation” of the home really meant.

Were there any more modest buildings that were saved under the auspices of historical preservation?

Maybe the most humble building that I wrote about in a bit of detail was an old cowshed that some men who were part of the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts, had heard about in the 1860s. It was potentially built from timbers from the 17th-century First Church of Salem.

So they went out and inspected this old cow shed and decided that it was definitely built from that first church. They reconstructed the church building, taking careful note of what they thought was the original material rescued from the cowshed, and what was filler material. And this reconstruction still stands on the grounds of the Peabody Essex Museum today.

We might say, "Well, that's demolition. That's not preservation in the case of Ashland. Or, that's clearly not the first church of Salem; that's bad preservation." What my book tries to do is not judge what was good or bad preservation, or to try to apply the standards of today, but to take people in the past on their own terms when they said that they were engaging in preservation. And then to look carefully at the details of what they did to understand why they thought what they were doing was maintaining a meaningful connection to the past.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.