How Horace Greeley Turned Newspapers Legitimate and Saved the Media From Itself

The 19th-century publisher made reform-minded, opinion-driven journalism commercially viable

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5c/21/5c217d53-68c2-43b3-b414-ff8709211974/horace-greeley-silhouette_copy.jpg)

December 3, 1840, a Thursday. A bank president in New Jersey goes missing in broad daylight, leaving his office in New Brunswick around 10 a.m. He is never again seen alive. Some say he’s gone to Texas, others say Europe. There are no leads, one way or another, for six days. Then, an impecunious carpenter is seen with a “handsome gold watch,” “unusually flush with money,” boasting of newfound liberation from his mortgage. The trail leads to his home, down the steps into his cellar, under hastily laid floorboards, and into the dirt beneath. There, in a shallow ditch, rests the lost banker, fully clothed, watch missing, skull split from a hatchet blow.

Details of the story are familiar. We know them from Edgar Allan Poe’s 1843 gothic horror, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” in which a murderer is tormented by the ceaseless pounding of the victim’s heart he’s buried under his floor. Poe knew the story because he read newspapers. If you were alive, literate, or just vaguely sentient in New York or Philadelphia (where Poe lived) in 1840 and 1841, you probably knew the story, too. You knew it because cheap newspapers covered it in all its gory details for months—covered it with the relentless persistence of the beating heart beneath the floor in Poe’s tale. Daily papers needed readers to survive, after all, and murders—the more shocking, the more grisly, the better—brought readers.

But there was one American editor who turned his gaze the other way, hoping to elevate rather than titillate. Horace Greeley thought he could fix American newspapers—a medium that had been transformed by the emergence of an urban popular journalism that was bold in its claims, sensational in its content, and, in Greeley’s estimation, utterly derelict in its responsibilities.

As the trial for the bank manager’s murder wound to a close in April of 1841, with the killer sent up the gallows, Greeley was just launching the daily newspaper that would make him famous, the New-York Tribune. He should have flogged the New Brunswick case for all it was worth. But the Tribune referenced it just twice. First, Greeley printed a short editorial comment on the killer’s execution, but nothing more: no reporter on the scene, no bold-faced headlines referencing “Peter Robinson’s Last Moments,” “Breaking the Rope,” or “Terrible Excitement.”

Then, two days later, Greeley let loose—not to revisit the killing or to meditate on the lessons of the hanging, but to excoriate the newspapers that had so avidly covered both. The coverage, he wrote, amounted to a “pestiferous, death-breathing history,” and the editors who produced it were as odious as the killer himself. “The guilt of murder may not stain their hands,” Greeley thundered, “but the fouler and more damning guilt of making murderers … rests upon their souls, and will rest there forever.” Greeley offered his Tribune, and crafted the editorial persona behind it, in response to the cheap dailies and the new urban scene that animated them. Newspapers, he argued, existed for the great work of “Intelligence”; they existed to inform, but also to instruct and uplift, and never to entertain.

Greeley tumbled into New York City in 1831 as a 20-year-old printer. He came from a New England family that had lost its farm. Like thousands of other hayseeds arriving in New York, he was unprepared for what he found. With a population over 200,000, Gotham was a grotesquely magical boomtown. Riven by social and political strife, regular calamities and epidemics, and the breakneck pace of its own growth, it was a wild novelty in America.

At least there was plenty of printing work to go around. The year after Greeley’s arrival, New York had 64 newspapers, 13 of them dailies. In many ways, though, the press was still catching up to the city’s fantastic new reality. The daily press was dominated by a small core of expensive six-cent “blanket sheets,” mercantile papers that were pitched to merchants’ interests, priced for merchants’ wallets, and sized—as much as five feet wide when spread out—for merchants’ desks. The rest of New York’s papers were weeklies and semiweeklies for particular political parties, reform movements, or literary interests. They tended to rise and fall like the tides at the city’s wharves.

Newspapering was a tough business, but in 1833 a printer named Benjamin Day began to figure it out. Day’s New York Sun didn’t look or feel or read or sell like any daily paper in New York at the time. Hawked in the street by newsboys for just a penny, it was a tiny thing—just 7 5/8” x 10 1/4”—packed with stories that illuminated the city’s dark corners. Where newspapers had mostly shunned local reportage, Day and his reporters made the city’s jangling daily carnival ring out from tiny type and narrow columns.

The formula was simple: “We newspaper people thrive on the calamities of others,” as Day said. And there was plenty of fodder, be it “fires, theatrical performances, elephants escaping from the circus, [or] women trampled by hogs.” And if accidents, or crime scenes, or police courts, or smoldering ruins offered up no compelling copy, the Sun manufactured it by other means. Take the summer of 1835, when the paper perpetrated the famous “moon hoax” with a series of faked articles about lunar life forms seen through a new telescope.

That same year an itinerant editor named James Gordon Bennett launched his penny daily, the New York Herald. There, he perfected the model that Day had pioneered, largely by positioning himself as an all-knowing, all-seeing editorial persona. In 1836, as the Sun and the Herald dueled over coverage of a prostitute’s murder, Bennett fully made his name. His dispatches offered lurid descriptions gleaned from the crime scene, where he claimed access as “an editor on public duty”; his editorials took the bold—and likely false—stance that the prime suspect, a young clerk from an established Connecticut family, was innocent. The Herald soon surpassed the Sun in circulation, drawing in even respectable middle-class readers.

The age of the newspaper had dawned, and Bennett crowned himself its champion. “Shakespeare is the great genius of drama, Scott of the novel, Milton and Byron of the poem,” he crowed, “and I mean to be the genius of the newspaper press.” Books, theater, even religion had all “had [their] day”; now, “a newspaper can send more souls to Heaven, and save more from Hell, than all the churches and chapels in New York—besides making money at the same time.”

Greeley, a prudish latter-day New England Puritan, looked on in horror. Bennett and Day were making money, but they did so by destroying souls, not saving them. The penny press betrayed the great power of the newspaper to inform, and shirked the great burdens of the editor to instruct. The power of the press was being squandered in an unseemly contest for the lowest common denominator. These “tendencies,” Greeley recalled in 1841, “imperatively called for resistance and correction.”

Resistance and correction found several expressions, beginning in 1834 with Greeley’s first paper, a “weekly journal of politics and intelligence” called the New-Yorker. There, Greeley promised to “interweave intelligence of a moral, practical, and instructive cast”; he promised to shun the “captivating claptraps” and “experiments on the gullibility of the public”; and he promised to do it all “without humbug.”

There were problems with this approach, beginning with the fact that it didn’t pay. Greeley’s limited correspondence during the New-Yorker’s run between 1834 and 1841 reveals the editor continually at or near the financial drowning point. There wasn’t much of a market for instruction and elevation in print, even at $3 a year. “I essay too much to be useful and practical,” he told a friend. “There is nothing that loses people like instruction.” Instruction, if served at all, was best delivered in small doses, and with “sweetmeats and pepper sauce” to make it go down.

And there was another problem: How much could a newspaper actually accomplish in correcting the sins of other newspapers? Printed content was like the paper money that was at the root of the era’s regular financial crises: there was too much of it, and no one quite knew what it was worth. The same week that Greeley debuted his New-Yorker, another city paper placed a mock want-ad seeking “a machine for reading newspapers,” one that could “sift the chaff from the wheat,” “the useful facts from idle fictions—the counterfeit coin from the unadulterated metal.”

Still, Greeley persisted—certain that the world just needed the right editor and the right newspaper. He put forward the Tribune in 1841 with the assurance that he had found both. Here would be a “newspaper, in the higher sense of the term,” more suited to the “family fireside” than a Bowery barroom. Its columns would be expurgated—no “scoffing infidelity and moral putrefaction,” no “horrid medley of profanity, ribaldry, blasphemy, and indecency.” In their place would go “Intelligence,” Greeley’s notion of journalism as a vehicle not just for news, but for ideas, literature, criticism, and reform.

The notion, like the uncouth, wispy-haired towhead himself, was an easy mark for Bennett, who took aim following Greeley’s sermon on the coverage of the New Jersey murder. “Horace Greeley is endeavoring, with tears in his eyes, to show that it is very naughty to publish reports of the trial, confessions, and execution,” Bennett wrote. “No doubt he thinks it’s equally naughty in us to publish a paper at all.” By Bennett’s lights, Greeley’s priggish objections came from his rural roots: “Galvanize a New England squash, and it would make as capable an editor as Horace.” Greeley was simply not up to the work of urban journalism.

But Greeley was shrewder than Bennett thought. True, he’d never quite shaken off the dust of the countryside, but that was by choice. Greeley used Bennett’s editorial showmanship as a foil to create his own journalistic persona—setting himself up as a newsprint version of a stock folk figure of the day: the wise country Yankee sizing up a world in flux. Bennett, the savvy urbanite, was the herald telling the city’s dark secrets; Greeley, the rustic intellectual oddball, was the tribune railing against them. There was room for both.

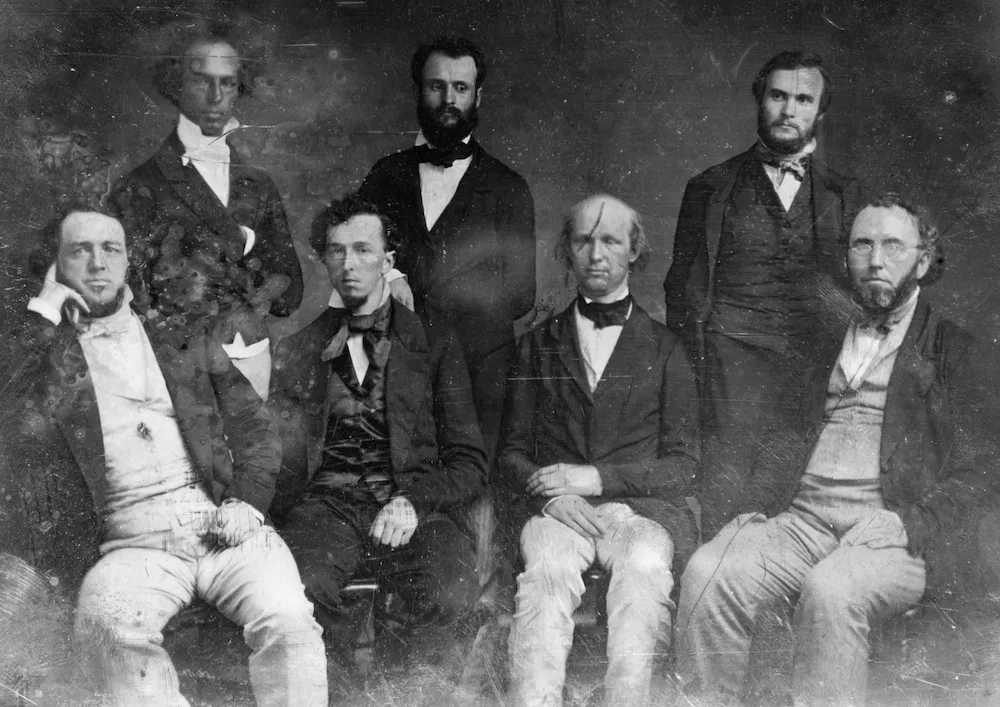

Greeley’s Tribune and Greeley the tribune would rise together over the next 30 years, paper and person often indistinguishable. The Tribune would never be the newsgathering operation that Bennett’s Herald was, nor would it match the Herald’s circulation in New York City itself. Instead, Greeley would use the city as a platform from which to project an editorial voice outward, to the country beyond. By the eve of the Civil War, the Tribune was reaching a quarter of a million subscribers and many more readers across the northern United States, and Greeley was the most visible and influential newspaper editor in the country. He was, by his own description, a “Public Teacher,” an “oracle” on the Hudson, “exert[ing] a resistless influence over public opinion … creating a community of thought of feeling … giving the right direction to it.” This was the work of journalism.

The idea landed with many of the readers who received the Tribune’s weekly edition. They regarded it as they would their own local weeklies: written, composed, and printed by one person. Greeley, in their belief, produced every word. He did little to discourage such impressions, even as the paper became a strikingly modern operation with a corps of editors, armies of compositors and printers, and massive steam-powered presses. “For whatever is distinctive in the views or doctrines of The Tribune,” he wrote in 1847, “there is but one person responsible.”

Horace Greeley never quite fixed popular newspapers, or the society that spawned them. The Herald continued to thrive, Bennett continued to bluster, crimes and calamities continued to happen. But Greeley did change newspapers. In making the Tribune into a clearinghouse of information as well as ideas, he made reform-minded, opinion-driven journalism commercially viable, and invented the persona of the crusading journalist. For the next three decades, until his death in 1872, Greeley would demonstrate the power—and limits—of that model.

James M. Lundberg is a historian at the University of Notre Dame. He is the author of Horace Greeley: Print, Politics, and the Failure of American Nationhood.