The Horse Flu Epidemic That Brought 19th-Century America to a Stop

An equine influenza in 1872 laid bare how essential horses were to the economy

:focal(692x211:693x212)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/88/4d884e2f-3d89-4272-aeed-c79429e55307/file-20201201-16-j69xty.png)

In 1872, the U.S. economy was growing as the young nation industrialized and expanded westward. Then in the autumn, a sudden shock paralyzed social and economic life. It was an energy crisis of sorts, but not a shortage of fossil fuels. Rather, the cause was a virus that spread among horses and mules from Canada to Central America.

For centuries, horses had provided essential energy to build and operate cities. Now the equine flu made clear just how important that partnership was. When infected horses stopped working, nothing worked without them. The pandemic triggered a social and economic paralysis comparable to what would happen today if gas pumps ran dry or the electric grid went down.

In an era when many looked forward to replacing the horse with the promising new technologies of steam and electricity, the horse flu reminded Americans of their debt to these animals. As I show in my new book, A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement, this reckoning fueled a nascent but fragile reform movement: the crusade to end animal cruelty.

The equine influenza first appeared in late September in horses pastured outside of Toronto. Within days most animals in the city’s crowded stables caught the virus. The U.S. government tried to ban Canadian horses, but acted too late. Within a month border towns were infected, and the “Canadian horse disease” became a North American epidemic. By December the virus reached the U.S. Gulf Coast, and in early 1873 outbreaks occurred in West Coast cities.

The flu’s symptoms were unmistakable. Horses developed a rasping cough and fever; ears drooping, they staggered and sometimes dropped from exhaustion. By one estimate, it killed two percent of an estimated 8 million horses in North America. Many more animals suffered symptoms that took weeks to clear.

At this time the germ theory of disease was still controversial, and scientists were 20 years away from identifying viruses. Horse owners had few good options for staving off infection. They disinfected their stables, improved the animals’ feed and covered them in new blankets. One wag wrote in the Chicago Tribune that the nation’s many abused and overworked horses were bound to die of shock from this sudden outpouring of kindness. At a time when veterinary care was still primitive, others promoted more dubious remedies: gin and ginger, tinctures of arsenic and even a bit of faith healing.

Throughout the 19th century, America’s crowded cities suffered frequent epidemics of deadly diseases such as cholera, dysentery and yellow fever. Many people feared that the horse flu would jump to humans. While that never happened, removing millions of horses from the economy posed a different threat: It cut off cities from crucial supplies of food and fuel just as winter was approaching.

Horses were too sick to bring coal out of mines, drag crops to market or carry raw materials to industrial centers. Fears of a “coal famine” sent fuel prices skyrocketing. Produce rotted at the docks. Trains refused to stop at some cities where depots overflowed with undelivered goods. The economy plunged into a steep recession.

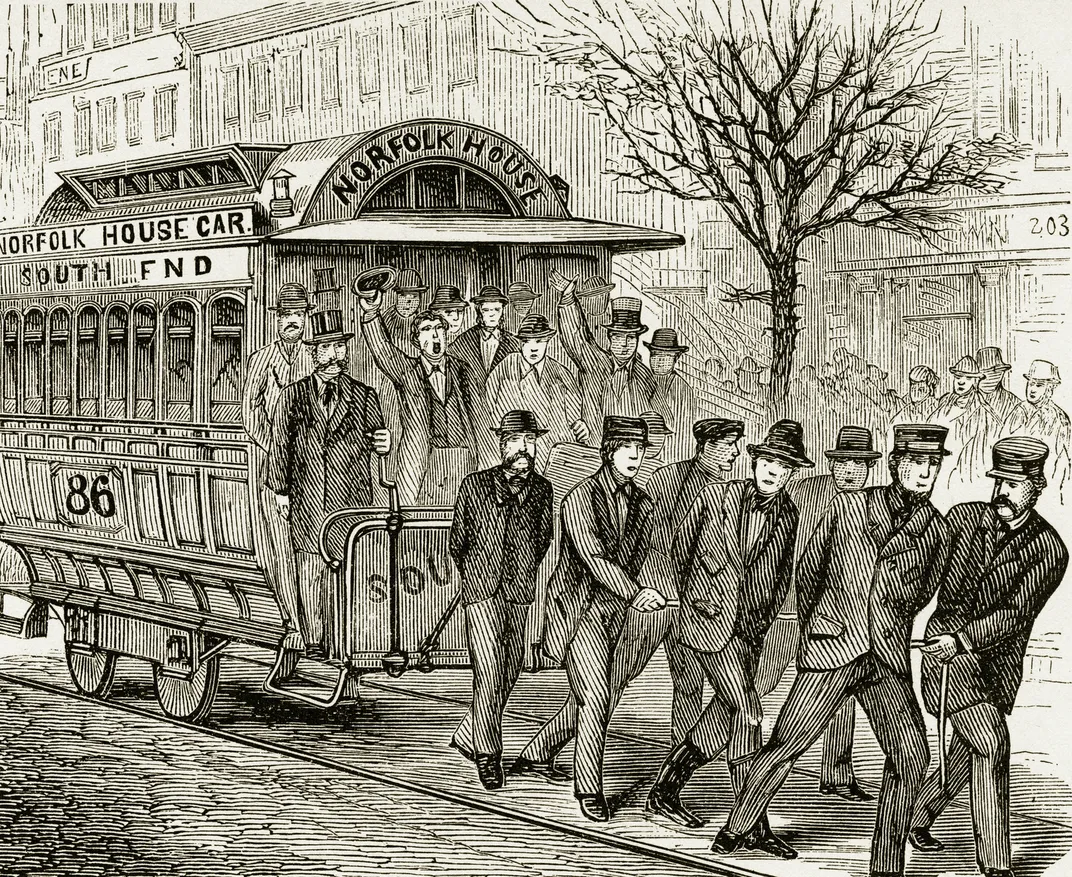

Every aspect of life was disrupted. Saloons ran dry without beer deliveries, and postmen relied on “wheelbarrow express” to carry the mail. Forced to travel on foot, fewer people attended weddings and funerals. Desperate companies hired human crews to pull their wagons to market.

Worst of all, firemen could no longer rely on horses to pull their heavy pump wagons. On November 9, 1872, a catastrophic blaze gutted much of downtown Boston when firefighters were slow to reach the scene on foot. As one editor put it, the virus revealed to all that horses were not just private property, but “wheels in our great social machine, the stoppage of which means widespread injury to all classes and conditions of persons.”

Of course, the flu injured horses most of all—especially when desperate or callous owners forced them to work through their illness, which quite often killed the animals. As coughing, feverish horses staggered through the streets, it was evident that these tireless servants lived short, brutal lives. E.L. Godkin, the editor of The Nation, called their treatment “a disgrace to civilization … worthy of the dark ages.”

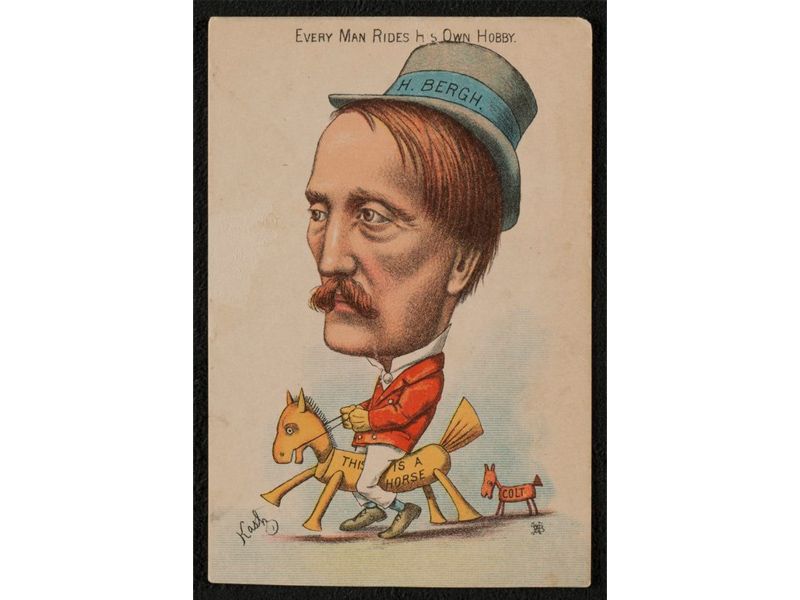

Henry Bergh had been making this argument since 1866, when he founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals—the nation’s first organization devoted to this cause. Bergh had spent most of his adult life pursuing a failed career as a playwright, supported by a large inheritance. He found his true calling at age 53.

Motivated less by the love of animals than by a hatred of human cruelty, he used his wealth, connections and literary talents to lobby New York’s legislature to pass the nation’s first modern anti-cruelty statute. Granted police powers by this law, Bergh and his fellow badge-wearing agents roamed the streets of New York City to defend animals from avoidable suffering.

As the equine flu raged, Bergh planted himself at major intersections in New York City, stopping wagons and horse-drawn trolleys to inspect the animals pulling them for signs of the disease. Tall and aristocratic, Bergh dressed impeccably, often sporting a top hat and silver cane, his long face framed by a drooping mustache. Asserting that working sick horses was dangerous and cruel, he ordered many teams back to their stables and sometimes sent their drivers to court.

Traffic piled up as grumbling passengers were forced to walk. Transit companies threatened to sue Bergh. Critics ridiculed him as a misguided animal lover who cared more about horses than humans, but many more people applauded his work. Amid the ravages of the horse flu, Bergh’s cause matched the moment.

At its darkest hour the epidemic left many Americans wondering whether the world they knew would ever recover, or if the ancient bond between horses and humans might be forever sundered by a mysterious illness. But as the disease ran its course, cities silenced by the epidemic gradually recovered. Markets reopened, freight depots whittled away delivery backlogs and horses returned to work.

Still, the impact of this shocking episode lingered, forcing many Americans to consider radical new arguments about the problem of animal cruelty. Ultimately the invention of electric trolleys and the internal combustion engine resolved the moral challenges of horse-powered cities.

Meanwhile, Bergh’s movement reminded Americans that horses were not unfeeling machines but partners in building and running the modern city—vulnerable creatures capable of suffering and deserving of the law’s protection.

Ernest Freeberg is a history professor at the University of Tennessee.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.