From the circular main hall of a University of Oxford library, a short corridor leads to a staircase that takes you down below street level. Beyond a door simply marked “Archive” is what looks like a normal office: fluorescent lights, cheap blue carpet and a row of plain gray rolling stacks. It doesn’t seem like the most fertile ground for archaeological discovery. But the hum of the air conditioner lets slip that this modest room is protecting something special. The temperature is held at 65 degrees Fahrenheit, while a humidifier keeps the moisture level tightly controlled.

This is the archive of the Griffith Institute, arguably the best Egyptology library in the world and home to the legacy of Howard Carter, the British archaeologist who led the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb 100 years ago this November.

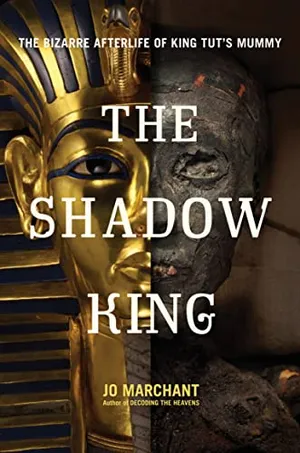

The story of Carter’s incredible find has been recounted so many times that it becomes more like a myth with every retelling. Some of the details wear ever deeper, like ruts, while others have faded from memory. But the notebooks, sketches, diaries and diagrams held in these dull-looking stacks contain the firsthand thoughts and impressions Carter recorded at the time. That’s what brought me here a few years ago, while researching my 2013 book, The Shadow King, which investigates our modern obsession with the elusive Pharaoh Tutankhamun. I wanted to look afresh at Carter’s discovery, working from original sources to recover lost details and bring the story back to life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d3/ca/d3cada4c-f3ac-41b0-9eda-531eb706bc2b/ttuuuut.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/75/bb/75bbfb55-c43d-40ac-93ea-e1a6c3179cff/gettyimages-3224919.jpg)

I visited the archive accompanied by its soft-spoken keeper, Jaromir Malek, and his assistant, Elizabeth Fleming. On the wall hung a somber portrait of Carter, his small, piercing, black eyes gazing irritably down. He looked less like a pioneering Egyptologist than an accountant or a banker. But Fleming assured me the man had vision and a sense of beauty. To prove it, she brought out perhaps the archive’s most aesthetically pleasing items—a collection of graceful watercolors painted by Carter himself during the last decade of the 19th century.

Carter’s artistic ability was what brought him to Egypt in the first place. He was born in London in 1874, the youngest of eight surviving children, and his father painted animal portraits—mainly dogs and horses—for rich local clients. Through his father, Carter met an Egyptologist named Percy Newberry, who in 1891 arranged for Carter, then only 17, to travel to Egypt to help record the extensive artwork being uncovered in tombs and temples around the country. Carter soon showed great promise as an archaeologist in his own right, learning rigorous methods from Flinders Petrie, who pretty much invented the idea of archaeology as a science and is today perhaps the only Egyptologist who can rival Carter’s fame.

In the watercolors Fleming showed me, Carter copied ancient Egyptian depictions of various animals and birds, painting them alongside their modern-day equivalents—inhabitants of the desert around him, from the scimitar-horned oryx and Nubian ibex to the Egyptian vulture, falcon and red-backed shrike. The pictures are elegant and effortless, with the attention to detail of someone who is both knowledgeable and passionate about his subject.

The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut's Mummy

Award-winning science writer Jo Marchant traces the mummy's story from its first brutal autopsy in 1925 to the most recent arguments over its DNA.

In the early 1900s, Carter took a series of jobs with the Egyptian antiquities service, holding several senior positions, including chief inspector of antiquities in Lower Egypt, a prestigious posting that included responsibility for the Great Pyramids, near Cairo. (He lost the job after instructing Egyptian guards to defend themselves against a party of drunken French tourists who tried to force their way onto a site.) His career in the service over, Carter moved to the city of Luxor, in southern Egypt, and scraped by selling his watercolors to tourists.

Carter’s dream was always to excavate a single site: the Valley of the Kings. This secluded, barren ravine, hidden behind limestone cliffs, lies just across the Nile from Luxor. Beginning in the early 19th century, Western excavators unearthed dozens of royal tombs dug into its walls. But the rights to dig in the valley were always held by others, and Carter could only watch as his rivals made a series of remarkable finds.

One of the most successful excavators was a retired American lawyer named Theodore Davis, who had a huge fortune but no patience for scientific procedure. Most of the royal resting places found in the valley were raided and emptied in ancient times, but Davis uncovered several intact tombs from the latter part of Egypt’s great 18th Dynasty, dating to 3,300 years ago. These included the pristine chambers of the parents of Queen Tiye (who lived circa 1390 B.C.E. to 1353 B.C.E.) and a mysterious tomb known as KV55, which held a cache of treasure and a nameless mummy suspected to belong to Tiye’s son, the rebellious pharaoh Akhenaten, who threw out Egypt’s traditional religion and built a new capital city in the desert at Amarna.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/27/e6/27e69b5e-5c0d-4691-8553-b146b4d155ad/canopic_jar_072261_with_a_lid_in_the_shape_of_a_royal_womans_head_30854_met_dp259121.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/df/ab/dfab4d67-4dbf-4435-a608-213e3ee67c50/tiye.jpg)

Carter, carefully studying the scars left in the valley by previous excavators, was certain there were places that hadn’t yet been searched, particularly in the central floor of the valley, not far from Davis’ finds, beneath a spot covered by ancient flood debris. He became convinced this area would yield the tomb of a little-known king named Tutankhamun, who ruled shortly after Akhenaten and restored Egypt’s traditional order.

Tutankhamun was one of the few 18th-Dynasty pharaohs for whom neither a tomb nor a mummy had been found. Several items among Davis’ finds bore his name, including a strange collection of large earthen pots, which were filled with broken pottery, bags of powder and dried flowers. What was more, the entrance to KV55 bore seal impressions associated with Tutankhamun, suggesting it had been closed during his reign. Carter hypothesized that if Tutankhamun had buried his predecessor here, he might have chosen a similar location for himself.

In 1914, Davis, close to death, finally gave up the rights to dig in the valley, famously saying, “I fear the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted.” Most other Egyptologists agreed with him, but Carter, who had by then teamed up with a rich patron—the English aristocrat George Herbert, Earl of Carnarvon—seized his chance.

Before they could start digging, however, World War I broke out, and excavations ceased. Carnarvon turned his estate in England, Highclere Castle, into a military hospital (more recently it stood in for the home of the Crawley family in the British television series “Downton Abbey”); Carter worked for the foreign office in the Middle East. But archaeological activity slowly restarted during the later years of the war, and in November 1917, Carter was finally able to pursue his dream.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0a/32/0a32f2ed-07a5-4564-9dc9-770945a4fd2b/burton_tutankhamun_tomb_photographs_1_009.jpeg)

Excavating the Valley of the Kings

In those days, the Valley of the Kings looked like a huge quarry, covered with piles of stones up to 30 feet high—waste left by previous excavators. Before he could investigate the triangular patch of central valley floor he’d chosen for his search, Carter had no choice but to clear tens of thousands of tons of this waste, then dig through an unexcavated layer of ancient flood debris all the way down to the bedrock.

To remove the rubbish, he borrowed a railway track from the antiquities service, with trucks that were pushed along the rails by hand. His team of local workmen and boys—the unsung Egyptians who carried out the real hard labor behind archaeological discoveries in the valley—used picks and hoes to fill their baskets, then emptied them into the trucks thousands of times each day. Over month after month of backbreaking work, these men literally moved mountains, clearing hundreds of square feet of the valley. The waste layers were so closely fused with the natural soil that the workers had to keep a close watch for charcoal and fish bones, which signaled whether they were digging through untouched layers of earth or artificial layers dumped by previous excavators.

Toward the end of that first season, in early 1918, the laborers uncovered the remains of a group of ancient workmen’s huts, dating to the 19th Dynasty, just after Tutankhamun’s time, right in front of the tomb of Ramses VI, which dated to around the same time. The huts were undisturbed, suggesting no one had penetrated the layer of flood debris beneath them since at least the second millennium B.C.E., and stood only 40 feet from the KV55 cache. If there were an intact, undiscovered 18th-Dynasty tomb somewhere nearby, beneath those ancient huts was the perfect place to look.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/42/ba421501-ed21-43e8-8cce-05074c59dcfa/1024px-carter_tomb_of_tut-ankh-amen_the_late_earl_of_carnarvon.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/88/85885d87-0208-4b76-b29f-f34aafdc1310/tomb.jpg)

Yet Carter didn’t. It’s a decision that provides fascinating insight into his character. Later, he maintained that excavating beneath the huts would have cut off visitor access to Ramses’ tomb, one of the most popular in the valley. But another explanation may have been that Carter, aware of how promising the site was, decided to save it for a time when Carnarvon’s enthusiasm for funding his work might flag.

Finding Tutankhamun’s tomb was undoubtedly important to Carter, but he also valued the less-glamorous task of carefully checking each unexcavated part of the valley before his patron found something else to do. The Egyptologist John Romer, in his classic 1981 book Valley of the Kings, pointed out that instead of following up on “such a plum site, so large and obviously untouched,” Carter next chose to investigate the foundation deposits of a previously known tomb. “Indeed,” wrote Romer, “most of Carter’s activities in the valley were of this type, designed to settle scholarly questions on the dating and origin of the tombs.” Perhaps we should see Carter as more methodically minded scientist than dogged tomb hunter.

Whatever the reason, Carter worked elsewhere for five depressing seasons. During those long years, he found hardly anything, just a few ritual deposits marking the foundations of known tombs and a cache of 13 alabaster vases, which Carnarvon’s daughter, Evelyn Herbert, who always accompanied her father on trips to Egypt, insisted on personally digging out of the ground.

It was a lonely time for the archaeologist, and he must have wondered if his critics were right. But he loved the remote and solitary valley, with its rugged rocks, which he once said “were not unproductive of delight.” Carter found it especially majestic during the 20-minute donkey ride to the home he’d built for himself, nicknamed “Castle Carter,” when the noise of his donkey’s footsteps was interrupted only by the booming of a desert eagle owl or the occasional howl of a jackal.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fc/88/fc888fb3-a977-4574-a04f-11886c68bd00/kv-wilkinson1830.jpeg)

By 1922, Carnarvon had serious doubts about continuing the work. He was tired of excavating with so little reward, not to mention the snide jokes of other Egyptologists. That summer, he invited Carter to Highclere, intending to bring the partnership to an end. But Carter didn’t give up easily. He finally told Carnarvon about the prime site beneath the workmen’s huts. Perhaps, to clinch the deal, Carter also mentioned a new clue suggesting that Tutankhamun really was buried in the valley. It had just come from Herbert Winlock, an Egyptologist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York who was studying the debris-filled KV55 jars inscribed with Tutankhamun’s name. Winlock, comparing the seemingly meaningless scraps with other discoveries elsewhere, finally realized what they were—the materials used in Tutankhamun’s embalming.

Ancient Egyptians didn’t throw away anything that touched the king’s body as it was being prepared for burial; instead, they carefully gathered all the rubbish and buried it close to the relevant tomb. Some of the jars contained the powdered salts embalmers used to dry out the body and the rags they cleaned up with afterward. Other pots contained broken pottery, animal bones and flower necklaces—likely the remains of the banquet held at Tutankhamun’s funeral, including floral garlands worn by the guests. It was the surest sign yet that the king’s tomb was nearby.

In October 1922, with Carnarvon’s support, Carter returned to the valley for one final season.

Discovering Tutankhamun’s tomb

At the Griffith Institute, Fleming brought out the notebooks describing what happened next. There was a small diary, cream-colored with a red spine, as well as a larger ring binder—Carter’s excavation journal. Together with popular books about Tutankhamun that Carter wrote over the following decade, they provide a pretty good sense of what he was up to in those historic days and weeks.

Carter started excavations on November 1, 1922, exactly where he had left off in 1918, by the workmen’s huts in front of Ramses VI’s tomb. He spent the next couple of days uncovering more huts, noting their details, then removing them to clear away the three feet or so of stony soil that lay between them and bedrock.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5a/8b/5a8bc9be-a05d-493e-b3e3-e88f4b9e2874/sepulchral_chamber.jpeg)

On Saturday, November 4, Carter arrived at the dig site at about ten in the morning to find his usually rowdy team of workmen strangely quiet. At first, he feared there had been an accident. Then, one of his foremen, the Egyptian Ahmed Gerigar, told him that the workers had discovered a step, cut into bedrock under one of the first huts they’d cleared.

As the men dug further, a steep, sunken staircase began to emerge, cut into the rock about 12 feet below the entrance of Ramses VI’s tomb. Carter tried to suppress his excitement. Toward sunset on Sunday, the men exposed the upper part of a door made from rough stones and covered with plaster. The seals on the door, showing the jackal god Anubis over nine bound captives—the official seal of the Royal Necropolis—were intact. There was no visible sign of exactly who was buried inside, but the style was 18th Dynasty.

Carter broke through the plaster and removed the stones from the upper right corner of the door. Then he shone in a flashlight. The passage was filled with stones and rubble—more evidence that the last people to enter had been the priests who sealed it, not thieves. “It was a thrilling moment for an excavator,” Carter wrote in his journal on November 5, “to suddenly find himself, after so many years of toilsome work, on the verge of what looked like a magnificent discovery—an untouched tomb.”

Carter knew he could proceed no further without his sponsor present. Reluctantly, he closed the hole he had made, and the next morning, he cabled Carnarvon at Highclere: “At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact, recovered same for your arrival, congratulations.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/d2/09d2b4b3-e73c-4517-863b-045a3d02ecfa/illustration_from_the_tomb_of_tut-ankh-amen_plate_xvi_interior_of_antechamber_northern_end.jpeg)

The next day, the men worked feverishly to protect the find from looters; they covered up the door and steps, then rolled boulders over the entrance. The tomb vanished, and more than once, Carter found himself wondering if finding it had even been real. He spent the next couple of weeks preparing to open the tomb and hiring staff, including Arthur Callender, an old friend and retired railway engineer who was to be his right-hand man in the work ahead.

Carnarvon and his daughter arrived in Luxor on November 22. By November 24, the workmen had reached the doorway. Now the lower part of the door was uncovered for the first time—and there on the door were seal impressions showing a basket, scarab beetle and the sun’s disk, the cartouche of none other than Tutankhamun. The workmen pulled down the rough stones of the door and began to empty the corridor behind.

By the afternoon of Sunday, November 26, after clearing a steep passage about 30 feet long, the workmen came to a second sealed door. Again, Carter removed stones to make a hole in the top corner. He poked an iron testing rod into the darkness, then lit a candle to check that the air was safe to breathe. Reassured that the air wasn’t poisonous, he widened the hole and looked in. Carnarvon, Herbert, Callender and several of the Egyptian foremen waited anxiously behind him.

Carter’s candlelight crept uninvited into the darkness. Inside the tomb, time creaked into motion. Blurred shapes came into focus. Objects lumbered into being. After thousands of years of silence, the tomb had visitors.

The treasures of Tutankhamun

From reading Carter’s diaries, Malek, keeper of the Griffith Institute’s archive, told me, “He was obviously a man of few words. He was very prosaic, very down to earth. But when you read Carter’s description of when they first opened the tomb, he suddenly becomes a poet.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/44/c344a7d5-e6ed-4d1a-a3c7-ac474df227df/tutankhamun_ushabti_2012.jpeg)

With white-gloved hands, Malek’s assistant, Fleming, pulled Carter’s yellowed journal from a cardboard case and laid it gently on a cushion. She found the famous page—square paper filled with neat, black ink—and started to read Carter’s stiff but evocative words:

It was sometime before one could see, the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker, but as soon as one’s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another.

At first, Carter thought he was looking at wall paintings; it was a moment before he realized he was seeing actual three-dimensional objects. Carnarvon couldn’t bear it any longer. “Can you see anything?” he demanded.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f4/63/f4631915-bd40-42fa-bb99-4811f3dc3dcf/tutankhamun_tomb_photographs_4_326.jpeg)

As with many details of this story, different sources give different accounts for what happened next. In his excavation journal, Carter wrote that he answered, “Yes, it is wonderful.” An account written by Carnarvon gives the rather less catchy “There are some marvelous objects here.” But the most memorable—and most quoted—version is the one Carter came up with later, probably with help from his co-author, Arthur Mace, for his 1923 popular account of the discovery, in which he simply says, “Yes, wonderful things.”

Widening the hole in the door, the others crowded together and shined a light into the darkness. What they saw arguably still stands as the most amazing archaeological discovery of all time.

Looming out of the darkness of the chamber were two ebony-black statues of a king with gold staffs, kilts and sandals; gilded couches with the heads of strange beasts; exquisitely painted ornamental caskets; dried flowers; alabaster vases; strange black shrines adorned with a gilded monster snake; white chests; finely carved chairs; a golden throne; a heap of curious white egg-shaped boxes; stools of all shapes and designs; and a scramble of overturned chariot parts, glinting with gold.

The impression was not so much that of an orderly royal tomb, Carter wrote in his journal on November 26, but “the property-room of an opera of a vanished civilization.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a5/ed/a5ed42c4-6bf4-476f-b5de-1428e8f56118/tutankhamun_tomb_photographs_2_011.jpeg)

The tomb that changed the world

News of the discovery quickly spread, along with a variety of tall tales. One local legend held that three mysterious airplanes had landed in the valley and taken off to an unknown destination loaded with treasure.

On November 29, Carter held an official opening of the tomb’s antechamber, attended by various Egyptian and foreign notables and a reporter from the London Times. The paper raved about the tomb’s contents: a child’s stool, quaint bronze musical instruments, a dummy for wigs and robes, and food including trussed duck and haunches of venison.

Archaeology was changed forever, and Carter, who might have retired from excavation after his final season with Carnarvon, faced a challenge greater than any archaeologist before him: recording, retrieving and conserving thousands of fragile artifacts from this packed space while the whole world was watching.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a4/59/a459c0ba-e769-4c0a-81d9-dfac9c3a5752/anuk.png)

Before long, the Valley of the Kings became like a little village, with Carter and his newly enlarged team of assistants—including draftsmen, a chemist and conservator, and a photographer—using a variety of nearby tombs for different purposes. The tomb originally holding the KV55 cache became a darkroom, the entrance hung with a pair of heavy black curtains. In the long, narrow passage leading into the tomb of Seti II, 300 feet long and just 12 feet wide, conservator Arthur Mace and chemist Alfred Lucas set up a laboratory. The deeper part was used for storage, while the upper section (where the electric lights could reach) hosted wooden tables, benches, and shelves filled with bottles of conservation materials, including acetone, paraffin, celluloid solution and beeswax.

Stabilizing the objects coming out of Tutankhamun’s tomb was almost impossibly difficult, as they were liable to fall apart at the touch. It took three weeks to empty a single casket of the king’s clothing; one robe alone sported more than 3,000 gold sequins and 12,000 blue beads, each in danger of falling off.

Meanwhile, tourists and journalists flocked to Luxor by the thousands. The city was so deluged by newspaper dispatches that three new telegraph lines were laid direct to Cairo, and a local hospital was turned into a telegraph office. Luxor’s two biggest hotels set up tents in their gardens, asking guests to sleep on army cots.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e2/d8/e2d84804-a3ba-4205-8749-e507cb6ff759/gettyimages-804455156.jpg)

Each day, visitors crossed the river on wooden sailing boats called feluccas, then headed into the valley by donkey, sand cart or horse-drawn cab. There, they made themselves at home, sitting on a wall around the top of Tutankhamun’s tomb. About once a day, Carter’s team brought out the most recently retrieved objects and carried them in a convoy to the lab. The priceless artifacts looked like casualties of war on their wooden stretchers, wrapped in surgical bandages and fixed with safety pins.

Carter himself was bombarded with letters and telegrams: congratulations, offers of assistance, requests for souvenirs, offers of money for everything from movie rights to copyright on Egyptian fashions of dress. He was given advice on how to preserve antiquities and how to appease evil spirits. Shoemakers wanted the design of the royal slippers, and grocers wanted parcels of mummified foods—apparently, they expected them to be canned.

Eventually, the contents of the tomb would number more than 5,000 items. Over the next eight years, Carter carefully worked his way through four densely packed chambers, revealing treasures ranging from jewelry and model boats to hunting chariots and an ostrich feather fan. The deepest chamber, nicknamed the Treasury, was guarded by a huge black jackal, representing the god Anubis, with a linen cloak, collar of blue flowers, claws of silver, and ears and eyes of gold.

Clues such as dirty footprints and fingermarks in jars of perfumed oil showed that there had indeed been ancient looters, though they didn’t get away with much. In a side room, personal possessions painted a picture of the human being behind all the royal gold and treasure. One sturdy wooden chest, made up of complicated partitions and drawers, was stuffed with knickknacks and playthings from Tutankhamun’s youth: anklets, pocket game boards, slings, paints, mechanical toys and a fire lighter. Carter scribbled details of them all on more than 3,500 notecards and hundreds of journal pages.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/26/31/26316a07-8afb-4094-a1af-0857df147d7a/tuts_tomb_opened.jpeg)

Perhaps most impressive of all was the king’s burial chamber, decorated with rich paintings and filled with four nested gilded shrines, at the center of which was a perfectly preserved sarcophagus made of pink quartzite. Reliefs of goddesses were carved onto each corner, protecting the sides and ends of the casket with their outstretched, winged arms.

Carter finally came face to face with the king himself on February 12, 1924. By then, Carnarvon had been dead nearly a year, having suffered blood poisoning brought on by an infection after he sliced the top off a mosquito bite while shaving—and inspiring the legend of Tutankhamun’s curse.

Opening the pharaoh’s sarcophagus, Carter recalled later, was the “supreme and culminating moment” that he had looked forward to since it became clear the chambers he’d discovered were an intact tomb. With a delicate pulley system, in front of an audience of dignitaries and VIPs, Carter slowly raised the huge, 2,500-pound stone lid. Inside, the contents were covered in shrouds. When he rolled them back, Carter wrote, “a gasp of wonderment escaped our lips, so gorgeous was the sight that met our eyes.”

Inside was a glorious figure, seven feet long and made of wood that was covered in gold. The observers didn’t yet know it, but this was only the outermost of three tightly fitting nesting coffins, each elaborately adorned, the inner one formed from solid gold. The form before them lay on a wooden bier, just as shown in the tomb paintings a few feet away. Its arms were folded across its chest, hands clasping a flail and crooked scepter made of gold and a ceramic glaze known as faience. The twin heads of a sacred cobra and vulture—protectors of Upper and Lower Egypt, respectively—were mounted on its golden forehead.

For ancient Egyptians, the coffin represented the king’s transformed immortal state, physically perfect and eternally young, with flesh of gold. But there was also a sign of human grief and frailty: a tiny wreath of olive leaves and cornflowers placed on the king’s forehead, with fragile petals that still had a tinge of blue.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/f1/60f19394-b34f-45c7-9303-511ffaa83584/diptych.jpg)

“Many and disturbing were our emotions,” wrote Carter. “Most of them voiceless. But, in that silence, to listen—you could almost hear the ghostly footsteps of the departing mourners.” According to the Times reporter present, the face of the coffin was so “remarkably real” that for a moment, the observers forgot they were gazing at a mere mummy case. It felt instead as if they were in the presence of some great, golden person lying in state.

In the world above, empires had risen and fallen; wars and natural disasters had wracked the land; civilizations had sprung up, developed and disappeared; major religions had come into existence and been superseded by others. Through it all, a few feet beneath the earth, this forgotten king had lain in his sarcophagus, his golden face and obsidian eyes staring up toward the sky.

Adapted from The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut’s Mummy by Jo Marchant. Published by Da Capo Press. Copyright © 2013 by Jo Marchant. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(2545x2012:2546x2013)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/10/76/10767286-87a9-4d2f-86b0-2cf73b7378cf/gettyimages-55995539.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jo.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jo.png)