How the Liberty Bell Won the Great War

As it entered World War I, the United States was politically torn and financially challenged. An American icon came to the rescue

:focal(2680x1933:2681x1934)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/6f/d16f30ac-03e5-4888-8bd8-708203ffe86c/apr2017_k13_libertybell.jpg)

Just weeks after joining World War I in April 1917, the United States was in deep trouble—financial trouble. To raise the money needed to help save the world from itself, the Treasury Department had undertaken the largest war-bond drive in history, seeking to raise $2 billion—more than $40 billion today—in only six weeks. The campaign’s sheer scope all but reinvented the concept of publicity, but it was still coming up short.

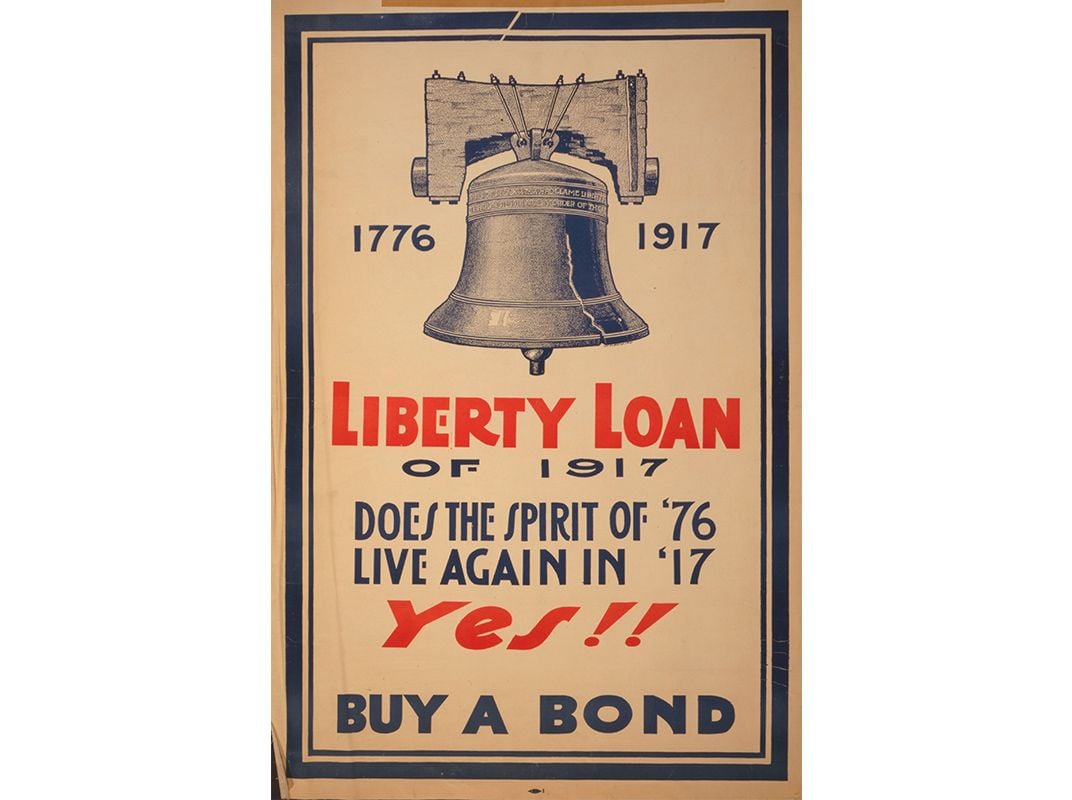

Despite endless appearances by movie stars (who had previously considered explicit politicking taboo), 11,000 billboards, streetcar ads in 3,200 cities and towns, and fliers dropped from planes, bond sales lagged. Treasury Secretary William McAdoo, who also happened to be the son-in-law of President Woodrow Wilson, needed some kind of national loyalty miracle. So he and his propaganda advisers, the Committee on Public Information, who had produced a series of clever posters (the Statue of Liberty using a phone, Uncle Sam carrying a rifle), decided to take one of their most arresting images and bring it to life, no matter how risky.

They would actually ring the Liberty Bell. They would ring it even if it meant that the most emblematic crack in political history would split the rest of the way and leave a 2,080-pound pile of metal shards. And the moment after they rang the Liberty Bell, every other bell in the nation would be sounded, to signal a national flash mob to head to the bank and buy war bonds.

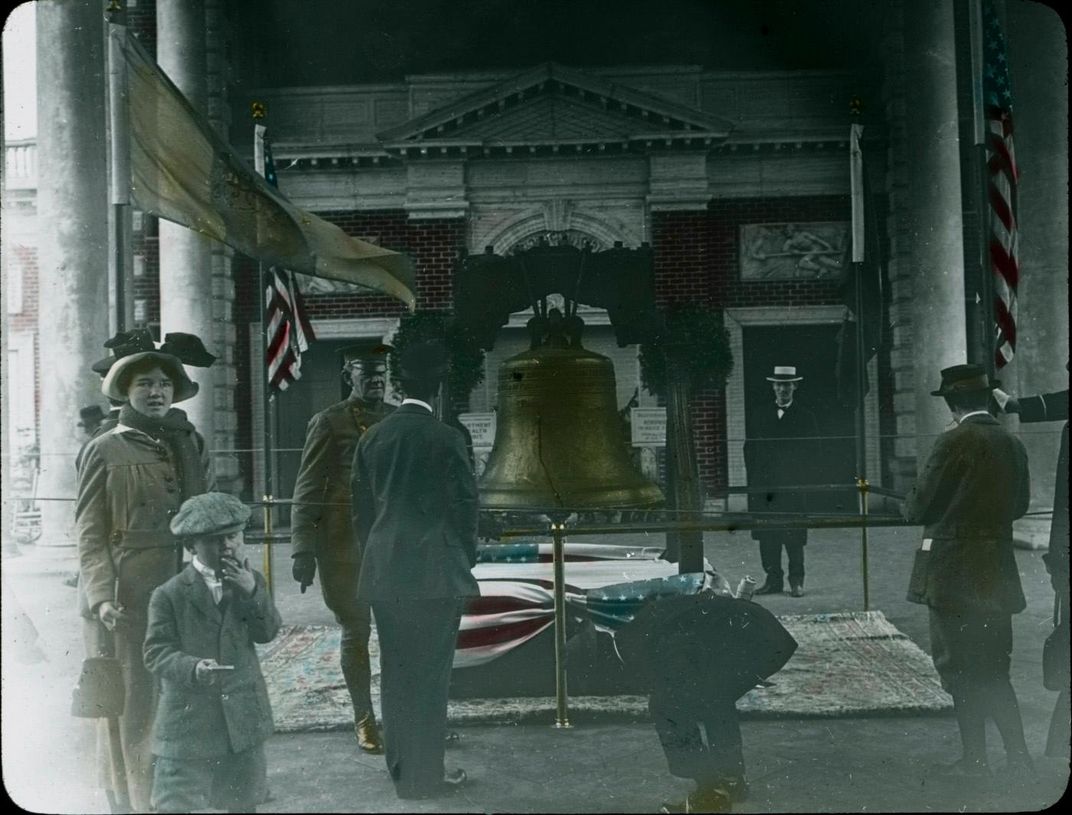

On the campaign’s final day—June 14, 1917, which was also Flag Day—Philadelphia Mayor Thomas Smith and his entourage approached Independence Hall just before noon. Thousands were already camped outside. Smith walked ceremoniously past the spots where Washington became commander in chief of the Continental Army and the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, and he approached the rear staircase, where the bell was kept, below where it had once hung.

The bell was normally enshrined in a ten-foot-high display case of carved mahogany and glass, but today it was fully exposed and rigged with microphones underneath, as well as a three-foot-long metal trumpet at its side to capture the sound for a Victrola recording. As Smith stepped up to the bell with a small golden hammer, telegraphers in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. awaited their cue to alert the thousands of their fellow Americans standing by in churches, fire stations and schoolyards, any place with an active bell tower. They were all clutching their ropes, anxious to join what the New York Times called a “patriotic clangor from sea to sea.”

Smith looked a bit tentative in his three-piece suit and wire-rim glasses as he raised his arm to strike. But as he brought his hammer down for the first of 13 times, to commemorate each of the original colonies, the Liberty Bell was about to assume its rightful place in history—and maybe help save the world.

**********

I have lived down the street from the Liberty Bell most of my adult life, so I have known it only as the main attraction at the site of our nation’s founding. Every year, more than 2.2 million people come to see it and do their best to resist touching it. I don’t always like the tourist traffic or getting caught behind horse-drawn carriages at rush hour, but there’s no question that the bell is the most enduring, powerful, yet approachable symbol of our country.

What is less appreciated is how this bell became The Bell. It was, after all, abandoned and sold for scrap in the early 1800s, after the national capital moved from Philadelphia to Washington and the state capital to Harrisburg, and the old Pennsylvania State House, where it hung, was scheduled for demolition. It was saved only by inertia; nobody got around to knocking the building down for years, and in 1816 a local newspaper editor went on a crusade to save the structure where the Declaration of Independence had been signed—which he rebranded as “Independence Hall.” Its clock tower was restored in the 1820s with a new bell, and the original was rehung inside from the ceiling and sounded only for historic events. It was rung in 1826, for the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration, and a few times in years afterward in memory of some founders. But it wasn’t called the “Liberty Bell” until 1835, and that was in a snide headline in an antislavery pamphlet, above an article noting all the slaves for whom the bell had never tolled. And its ascension as a national relic still had decades to go.

The Bell reportedly cracked after being rung for Washington’s birthday in 1844. (What seems to be the first mention of its being cracked appeared that year in the Philadelphia North American.) In an attempt to fix it, the city had the hairline crack drilled out to half an inch and rivets inserted on either end of the new, more visible crack, thinking to make the bell more stable and even occasionally ringable. Soon after, it was brought to lie in state on the first floor of Independence Hall. At the 1876 world’s fair in Philadelphia, more visitors saw replicas than the real thing because the fairgrounds were so far from the Hall. The actual Bell was taken on a half-dozen field trips between 1885 and 1904, to the two world’s fairs in Chicago and St. Louis and to New Orleans, Atlanta, Charleston and Boston, but it was retired from travel on the grounds of fragility without ever appearing west of the banks of the Mississippi.

While popular, the Bell didn’t truly come of age as a national symbol until World War I. Its rise to glory began with a hastily organized train trip across the country in the summer of 1915, as President Wilson, former President Theodore Roosevelt and other leaders felt the need to whip the nation into a patriotic frenzy to prepare for the war to end all wars, and culminated in the war-bond drives of 1917 and 1918.

I stumbled upon this resonant national drama while researching the World War I sections of Appetite for America, my book on the railroad hospitality entrepreneur Fred Harvey. Later, with the help of archivists all over Philadelphia—but especially Robert Giannini and Karie Diethorn at the Independence National Historical Park archive, and Steve Smith at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania—I was able to uncover many unseen documents, journals, scrapbooks and artifacts; explore and cross-reference newly digitized historical newspapers; and rescue more than 500 archival photographs, which the Independence National Park and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia then had digitized. This first in-depth reading of the Bell’s history in the digital age allows us a much better understanding of its journey not only across the country, but also across our history.

In three short years, the Liberty Bell changed America and empowered America to change the world. During its excursion in 1915, nearly a quarter of the nation’s population turned out to see it; in each of the 275 cities and towns where it stopped, the largest crowds ever assembled to that point greeted it. Many more Americans gathered along the train tracks to see it pass by on its specially constructed open car. At night a unique generator system kept a light on it, so it glowed as it traversed the countryside, a beacon across the land.

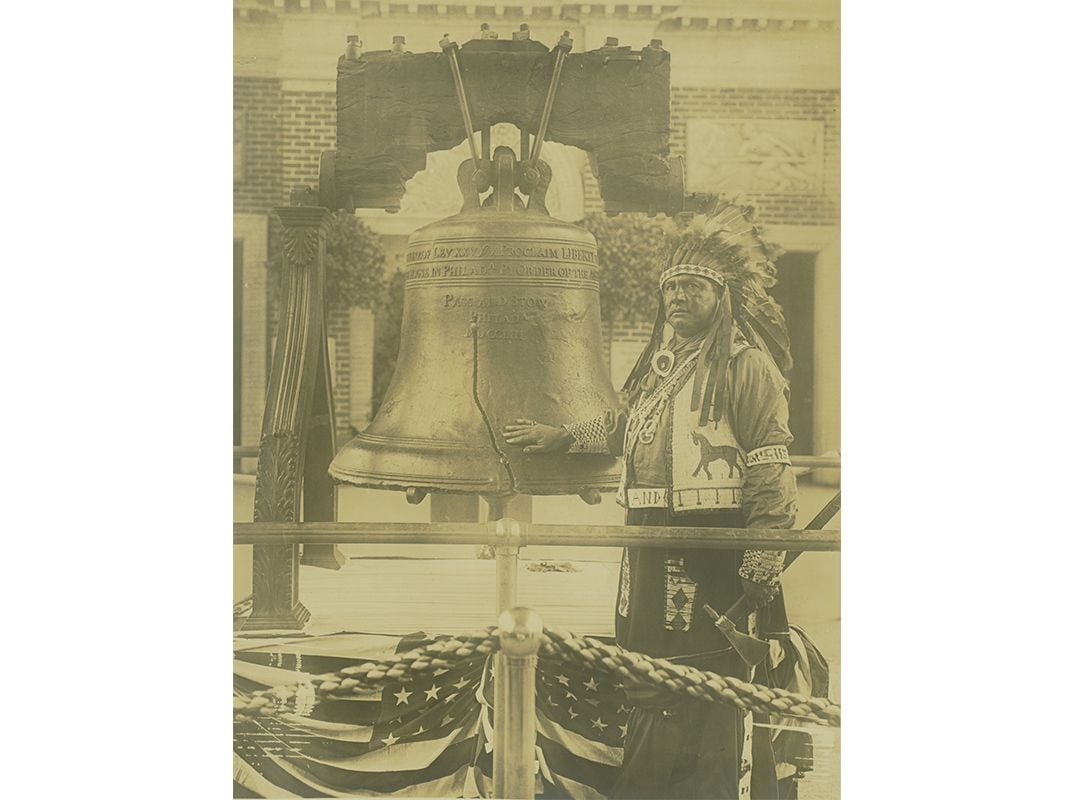

Over four months on the road, the Bell became a unifying symbol in a nation that had been increasingly divided. It went west across the northern United States, through Eastern and Midwestern cities wrestling with racism and anti-Semitism fueled by a backlash against immigrants from our wartime enemy, Germany, and then it continued through the Pacific Northwest, where Native Americans and Asian-Americans struggled for their rights. It returned through Southern California and the Southwest, where Native Americans from other tribes and Hispanics fought for inclusion, and then into the Deep South not long after the premiere of The Birth of a Nation, the lynching in Georgia of a Jewish factory manager named Leo Frank and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

Among the passengers on the Liberty Bell Special, as the train was called, was Philadelphia City Councilman Joe Gaffney, who kept a diary he later turned into a slide presentation, which I discovered in the bowels of the Independence National Historical Park archive. “It seemed to have been the psychological moment,” Gaffney wrote, “...when some such enterprise was needed to arouse the latent patriotic impulses of the people and give them opportunity to show their love of flag and country.”

After the trip, it was no surprise that the Treasury Department saw the Bell as its last best hope to persuade Americans to support the world’s first democratically financed war. Historian Frank Morton Todd, writing in 1921, claimed that during the “fiery test” of the Great War, nothing short of a Liberty Bell tour could have “stimulate[d] patriotism and [brought] the public mind to dwell on the traditions of independence and democracy that form the best inheritance of the Americans.”

**********

Of course, Americans came into their best inheritance only after some of the shabbiest dynamics of their political system played out. The story of the 1915 Bell tour is also the story of two of the nation’s most progressive mayors and the epically corrupt U.S. senator who hated them.

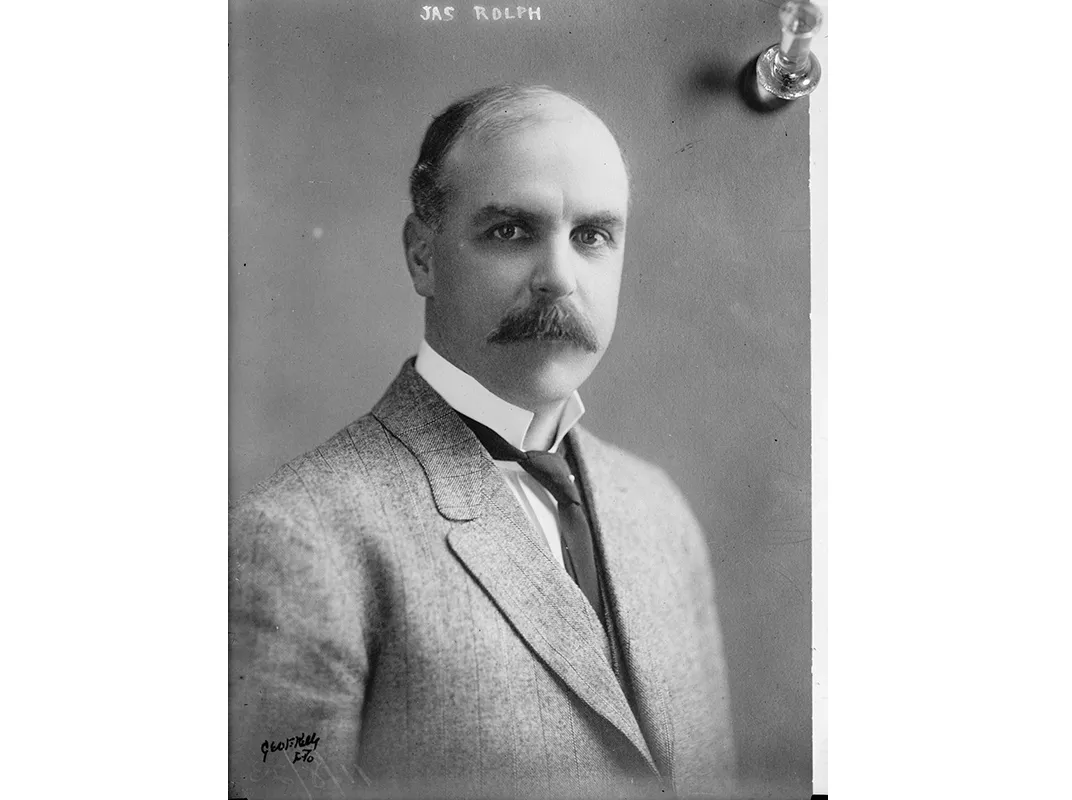

The idea of sending the Bell to California had its loudest champion in San Francisco Mayor James “Sunny Jim” Rolph, a businessman who had risen to prominence running relief efforts in the Mission District while riding a white stallion through the streets of his broken neighborhood. When his city was awarded the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a celebration of the completion of the Panama Canal and the first American world’s fair to be held on the West Coast, he started obsessing over the Bell. Soon the fair organizers, the city’s teachers and schoolchildren and San Fran-cisco-based power publisher William Randolph Hearst joined him. They all came to believe a Bell expedition was the only way California—indeed, the entire West—could feel, for the first time, fully connected to the “original” America, sharing in its history as well as its future.

Philadelphia’s mayor at the time, a Republican businessman named Rudolph Blankenburg, thought it was a great idea. Blankenburg was a scrawny German immigrant in his 60s whose biblical white beard gave him the look of someone’s little old European grandfather—until he leapt to his feet and began swinging his fists in splendid oratory. He had been elected in 1911—the first time he held public office—as a progressive tied to Teddy Roosevelt’s third-party presidential campaign. Given Philadelphia’s reputation as the most corrupt city in the most corrupt and powerful state in the nation, the New York Times called his victory “the climax of one of the greatest reform campaigns ever fought in this country.”

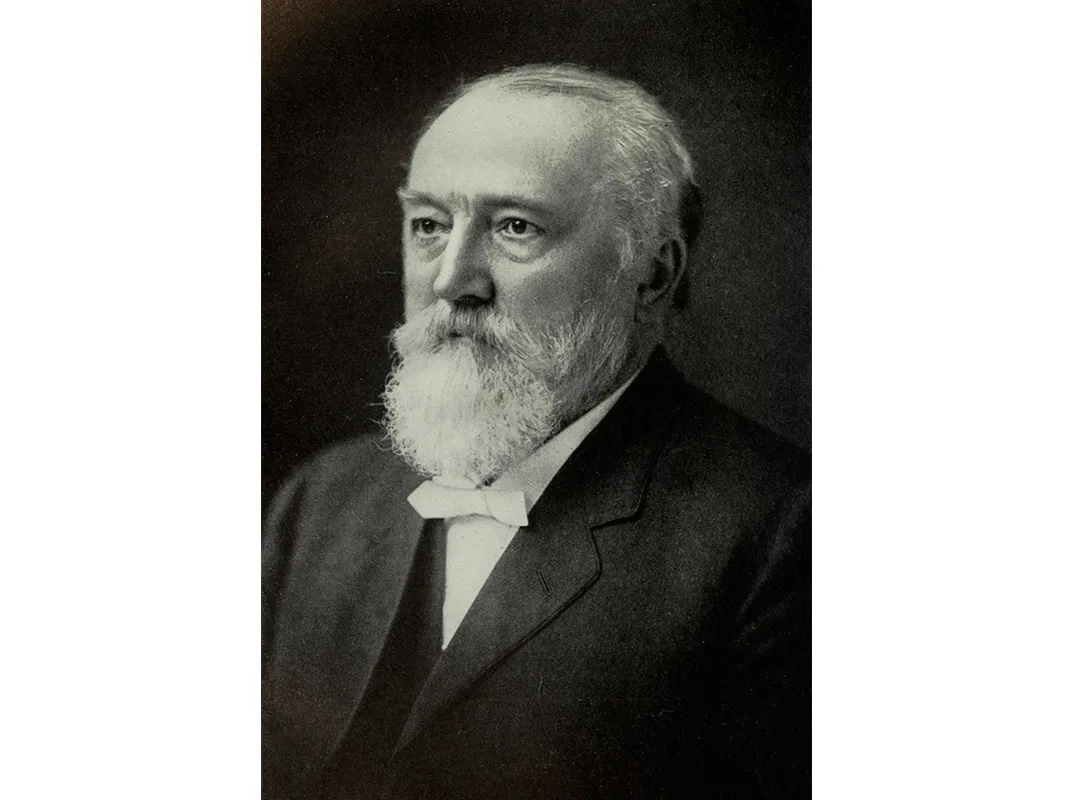

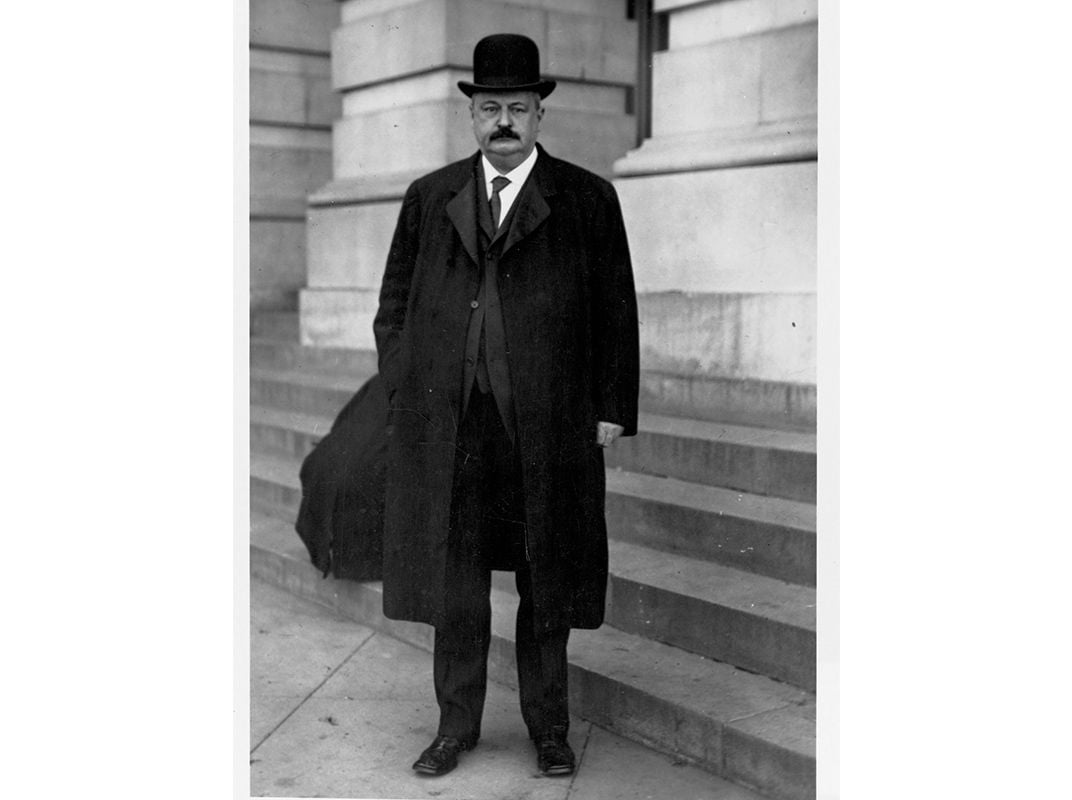

Nobody was more upset about Blankenburg’s election than U.S. Senator Boies Penrose of Pennsylvania, a Harvard-educated lawyer and Republican Party boss. Known as “the Big Grizzly,” Penrose was one of the nation’s most grotesquely influential men, his dining habits widely viewed as a metaphor for his hunger for power. A huge, Weeble-shaped man with a round face, squinty eyes, thick mustache and ever-present bowler, he was known to order so much food in restaurants, and to devour so much of it without benefit of utensils, that waiters would put up screens around his table to spare other patrons the sight. He was also the rare public figure who remained unmarried throughout his career, boasting of his abiding love of prostitutes because he didn’t “believe in hypocrisy.”

Penrose made it his mission to torpedo any initiative Blankenburg undertook. So when the mayor came out in favor of sending the Bell to San Francisco, all the old-line Republicans in Philadelphia followed the Big Grizzly and opposed it. The cities argued about it for almost four years. Philadelphia lawmakers and metallurgists banded together to insist that the Bell should never leave Independence Hall again, for its own protection. Besides, they argued, the American roadshow had become undignified.

“The Bell is injured every time it leaves,” claimed former Pennsylvania governor Samuel Pennypacker, because “...children have seen this sacred Metal at fairs associated with fat pigs and fancy furniture. They lose all the benefit of the associations that cling to Independence Hall, and the bell should, therefore, never be separated from [Philadelphia].”

With San Francisco’s fair about to open in February 1915, Blankenburg had failed to get permission for the Bell trip, so he offered the next best thing: a ringing of the Bell that would be heard over the new transcontinental phone line Bell Telephone had just completed, 3,400 miles of wire strung between 130,000 poles across the nation. When the Bell was sounded at 5 p.m. Eastern time on Friday, February 11, two hundred dignitaries listened on candlestick phones set up at the Bell office in Philadelphia, along with an additional 100 at the Bell office in San Francisco. In Washington, Alexander Graham Bell listened in on his private line, one of the perks of having patented the telephone.

That call was supposed to end the discussion, but Sunny Jim kept pushing. Eventually President Wilson and ex-President Roosevelt joined him. Their pressure led to some tentative city council action, but nothing got funded or finalized until after May 7, 1915, when the Germans sank the British liner Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, creating the first American casualties of World War I. After that, the city powers allowed Blankenburg to risk letting the Bell make a whistle-stop tour of America.

As soon as it was clear the Bell would travel, the discussion about its crack and physical condition stopped being political and became very practical. The city heard from every expert (and crackpot) in the country with an idea about how to repair, restore or otherwise de-crack the Bell. There were suggestions from the Department of the Navy, major foundries, even garages around the country, all offering to heal the fracture for the good of the nation. Blankenburg, however, was appalled by the idea. He made it clear that the crack would never be “fixed” as long as he was the guardian of the Bell.

The Pennsylvania Railroad had only weeks to prepare for a trip that normally would have taken months or years to plan—including the construction of the best-cushioned rail car in history, with the biggest springs ever used. The Liberty Bell Special would be a private, all-steel train with luxurious Pullman cars—sleepers, a dining car and a sitting car—the very best the “Pennsy” had to offer.

The train was originally going to be one car longer, with a sleeper for the mayor, his very politically active wife, Lucretia Mott Longshore Blankenburg (who had recently helped create the Justice Bell, a copy of the Liberty Bell intended to promote women’s suffrage), and some family and staff. But, like everything else during his administration, Rudy Blankenburg’s Liberty Bell trip became enmeshed in ugly city politics. Even though he had agreed, up front, to pay all the expenses for himself and his family, his political opponents made the trip out to be a “junket” that was wasting taxpayer money.

Blankenburg, who deserved the honor not only for his difficult time as mayor but also for a lifetime of service to Philadelphia and the nation, announced that he would not be able to make the trip. He blamed it on his health, but everyone knew different.

Photos From the Liberty Bell Whistle-Stop Tour

Since Blankenburg was the nation’s most prominent German-American public official, President Wilson invited him to come along on a cross-country series of “loyalty lectures” to remind immigrants of how important it was that they support the United States over their homelands.

Blankenburg doubled down on his role as a national spokesman for its message. He not only lectured to immigrant groups about loyalty, but also made in-your-face speeches to self-proclaimed “Anglo-Saxons” about their rising racism. At a banquet at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, he threw down the challenge to a large group of white civic leaders who were expecting light after-dinner remarks.

“The notion of a small but clamorous section of Americans, who blazen forth their fancied claim to superiority over the rest of their countrymen by calling themselves the ‘Anglo-Saxon race,’ is as absurd as it is unsound,” he said. “Yet we often hear that the Anglo-Saxon race should dominate our country. There is no Anglo-Saxon race....An overwhelming majority of our white population is a mix of all white races of Europe—Teutonic, Latin, Slav. And where would you place the ten million colored people who live among us?

“It is important to prepare against a possible foe abroad, but more against the domestic foe who may, unrecognized for years, appeal to our prejudice, our love of riches, our political ambitions and our vanity....Let us, therefore, abolish all distinctions that may lead to ill feeling and let us call ourselves, before the whole world, Americans, first, last and all the time.”

**********

Blankenburg ordered that Independence Hall remain open late on Independence Day 1915. He wanted Philadelphians to have a chance to “say goodbye to the Liberty Bell.” Just in case they never saw it in one piece again.

The next day, at 3 p.m., the Liberty Bell Special pulled out of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s main Broad Street Station. The passengers on the train—mostly city councilmen and their families—were in no way prepared for the volume of people who greeted them. At one of the first stops, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, so many people gathered that no one on the train could tell where the crowds ended.

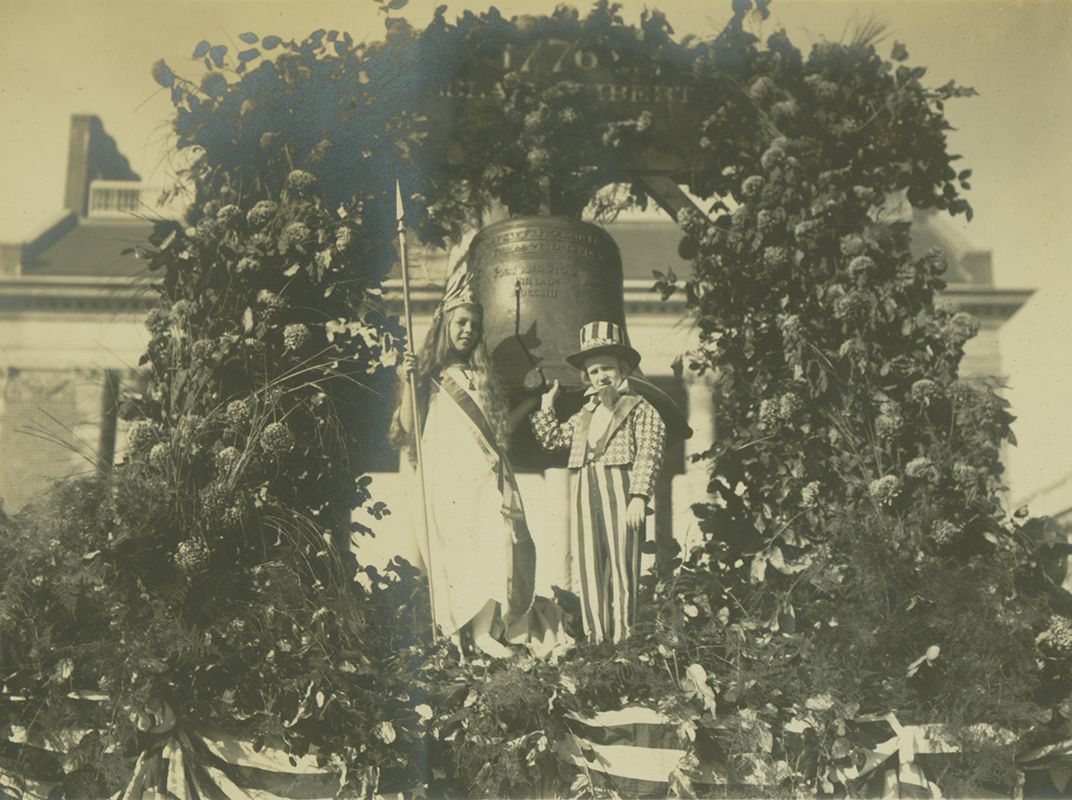

The Bell hung from a wooden yoke bearing the painted words “Proclaim Liberty—1776,” a brass railing its only protection from the mobs. The privilege of touching the Bell was supposed to be reserved for blind people, but the guards often allowed babies and toddlers up over the railing for a closer look and a photo op. “They set the little ones upon the rough, black lip of the Liberty Bell,” a reporter for the Denver Times wrote, “...and they placed both hands upon the Bell or pressed their lips against its cold surface, beamed suddenly and dimpled into smiles as if the great bell had whispered a message to them.”

Adults who got close enough asked the guards if they could touch the Bell with something, anything.

“Women drew gold and diamond bracelets from their arms without fear of pickpockets from the vast mob,” the Times reporter wrote. “Little children drew rings from their fingers and took gold lockets and chains from their necks. Prosperous businessmen, who looked as if sentiment played a small part in their everyday dealings with the world, handed up heavy gold watches and chains. Negroes, who showed a solid and dazzling expanse of white teeth, and even men ragged and unshaven, hobos apparently, dug down into their pockets and pulled out dilapidated pocket knives with the same simple but fervid words: ‘Please touch the bell with that.’”

In the first 24 hours, the train stopped in Frazer, Lancaster, Elizabethtown, Harrisburg, Tyrone, Altoona and Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania; in Mansfield, Crestline, Bucyrus, Upper Sandusky, Dunkirk, Ada, Lima and Van Wert in Ohio; in Fort Wayne, Plymouth and Gary in Indiana before heading to Chicago. (This itinerary represents both the official published schedule and the typed lists of 103 cities added along the way that I discovered in the records of Philadelphia’s Chief of City Property.)

The Liberty Bell had never been farther west than St. Louis, and that trip had been a crucial decade before. So as the Liberty Bell Special crossed into the Great Plains and across the Rockies, it passed through cities that were relatively new—some only recently created by railroads—and populated by citizens more likely to be struggling to understand their place in America.

The Philadelphians were constantly astonished by what they saw on, and from, the train.

“In Kansas City, an old colored man who had been a slave came to touch it—he was 100 years old,” recalled James “Big Jim” Quirk, one of four Philadelphia police officers assigned to guard the Bell. (One of his descendants, Lynn Sons, shared with me the archive Quirk left his family.) When they pulled out of another town, “an aged Mammie hobbled to the door of her cabin near the tracks, raised her hands and with her eyes streaming tears called out, ‘God Bless the Bell! God Bless the Dear Bell!’ It got to us somehow.”

In Denver, a group of blind girls were permitted to touch the Bell, but one of them started sobbing and exclaimed, “I don’t only want to touch it. I want to read the letters!” While the crowd was hushed, the girl slowly read the inscription by running her fingers over the raised letters, methodically calling the words to her companions: “Proclaim...Liberty...throughout...all...the...land.”

As the train approached Walla Walla, Washington, there was panic aboard as small, hard projectiles began raining down on the Bell. While the guards first worried someone was shooting at it, they looked up to a ridge where some boys were standing and decided they were stoning the train. This “first act of vandalism” against the Bell made national news, although police later determined that the boys hadn’t thrown anything, that the stones had shaken loose from the ridge when the train went by.

In Sacramento, the Bell even helped catch a criminal: the notorious safe-robber John Collins, who had eluded capture until Max Fisher, an officer from the police department’s criminal identification bureau, recognized him among the crowd of those who couldn’t resist coming to see the Liberty Bell. Fisher promptly had Collins, whom he considered “one of the cleverest crooks in the country,” arrested.

The Bell arrived in San Francisco on July 17. City officials proclaimed that it had been unharmed by the journey, but privately they and the Pennsylvania Railroad worried that the Bell car vibrated far more than they had predicted, and they started searching for a way to make sure the Bell was safer on the way back.

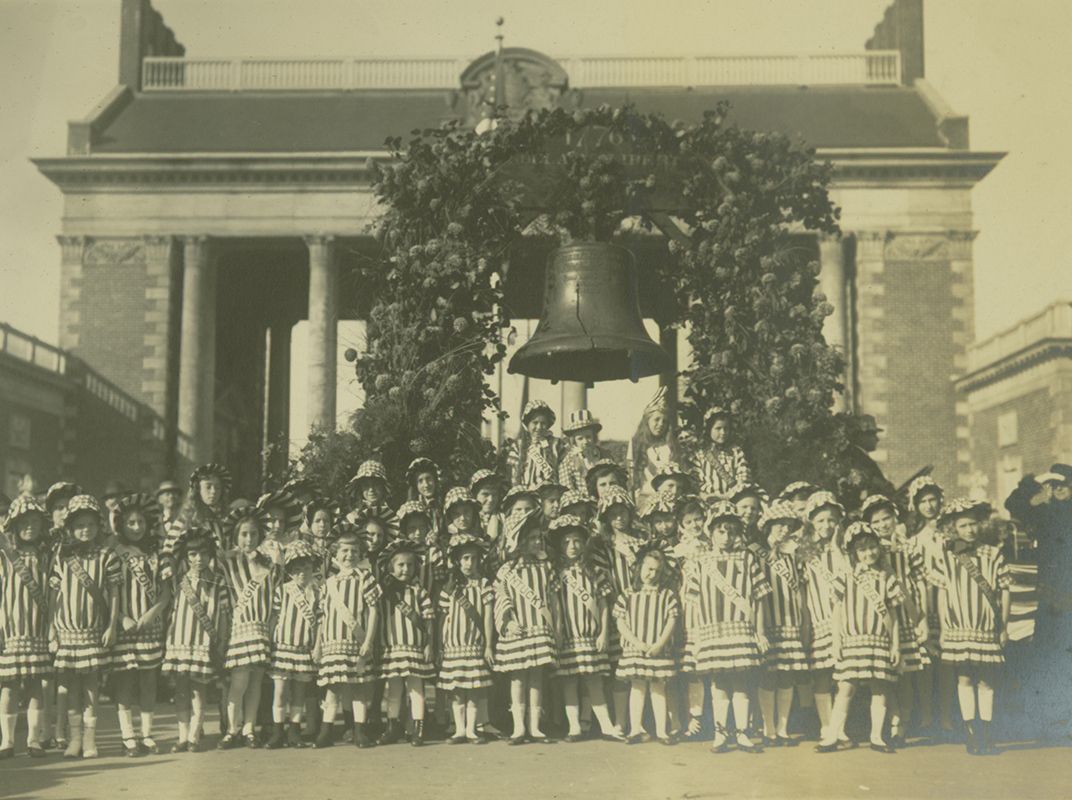

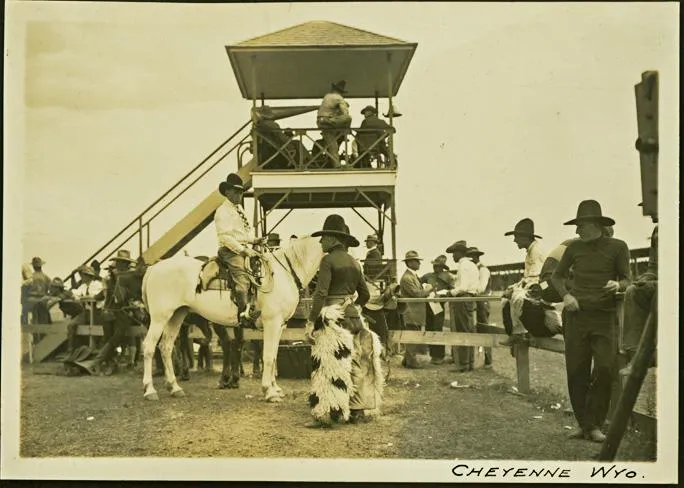

The city held gala Bell ceremonies, which doubled as a huge preparedness rally for the coming war. Big Jim Quirk never forgot the tens of thousands of flowers on the parade floats, or the roses that women and children tossed at him as the Bell passed. (“Tossed is right,” he joked, rubbing his left ear in recollection. “The ladies weren’t always the best shot, and [someone]...beaned me with the thorniest American Beauty you ever saw.”)

The Bell then went directly on display at the fair in the Pennsylvania pavilion, where it remained for four months. Its platform rested on a priceless 400-year-old Persian rug, and it was cordoned off with red-white-and-blue silk rope—which Eva Stotesbury, the redecorating-obsessed second wife of the richest man in Philadelphia, had ordered. Each evening guards removed it from the platform and stored it in what fair officials promised was an “earthquake-proof” vault.

The Bell became, in the opinion of many, the exhibit that saved the fair from what had been pretty underwhelming attendance. Fairgoers took an estimated 10,000 photos of it every day.

Even people who had seen the Bell many times, like Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, were fascinated to view it in this incongruous setting. Teddy Roosevelt took one look at it and declared, “Can any puerile, peace-talking molly-coddle stand before this emblem of Liberty without a blush of shame?”

It made many people weep, although others admitted that, frankly, they thought it would be bigger.

**********

Four months later, on November 10, 1915, San Francisco gave the Liberty Bell the send-off it deserved, a massive parade celebrating American patriotism.

While nobody knew it at the time, a group of preparedness extremists planned to blow up the Bell during the parade, hoping to prod the United States into the war faster. These extremists reportedly paid a bootblack $500 to drop off their suitcase bomb near the Bell—which was spared only because the bootblack changed his mind at the last minute and threw the suitcase into the bay. The terror plot was revealed months later when the same group bombed another San Francisco parade, killing ten people.

After the parade, the Bell was loaded onto the Liberty Bell Special, and most of the Philadelphia city councilmen who had accompanied it west returned for the ride home. They were joined by a controversial new passenger: Senator Boies Penrose, who suddenly wanted to be part of the Bell tour now that it was a national sensation. After appointing himself “orator in chief” for the return trip, he began appearing in nearly every photo taken aboard the Liberty Bell Special, looming in his dark suit, overcoat and bowler.

The Big Grizzly claimed to be doing his patriotic duty by joining the excursion, but since he was considering running for president against Wilson in 1916, it is more likely he viewed this as a taxpayer-funded whistle-stop tour through the Southwest and South, where voters knew little about him.

The Bell headed south for a three-day residence in San Diego, where a smaller world’s fair was underway, before the long journey home began. It hugged the Mexican border all the way into Texas. In Arlington, in the heart of the Lone Star State, a riot broke out when a young black girl kissed the Bell. “A crowd of fools and idiots gathered,” the Chicago Defender, a leading black newspaper reported, “and, because an innocent child, a mere baby, showed appreciation of well-trained parents and kissed the old bell whose touching appeal first kindles the fires of patriotism in the bosom of American citizens, she was jeered, hissed, scolded and cursed, and efforts [were] made to do violence.” The Defender’s reporter added: “No act, however skillfully planned with the brains of satan, would compare with this vile spirit.”

The train went to New Orleans, then north through Mississippi and Tennessee. In Memphis, the crowds pushing to see the Bell crushed a young woman to death. And only five hours after she died, as the train pulled into Paducah, Kentucky, two warehouses burst into flame just a thousand feet from where the Bell car was parked. Station crews immediately attached the Bell to another engine and dragged it to safety.

From there the train visited St. Louis, then leapfrogged through Indianapolis, Louisville and Cincinnati, where the director of a school choir that would perform “Liberty Song” at trackside announced he was deleting a reference to “slavery’s chains” being “ground to dust” because it did not “strike a harmonious chord.”

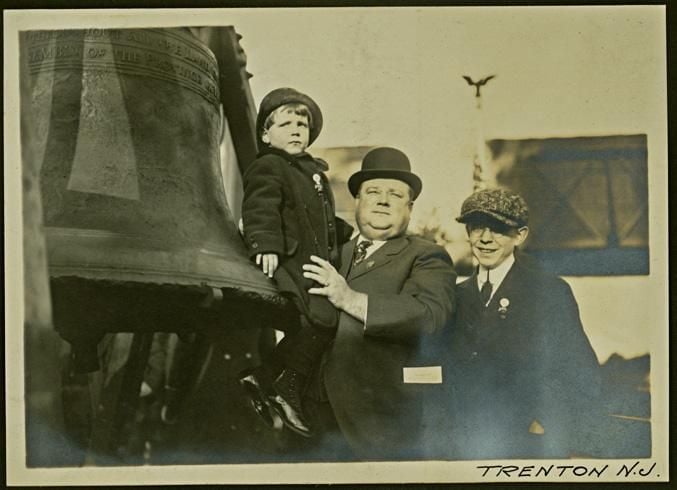

As the Liberty Bell Special headed for Pittsburgh, and the last straight shot of Pennsylvania Railroad tracks home to Philadelphia, it was diverted all the way up to Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse and Albany, before heading south through the Poconos and Trenton and finally home. The announced reason for the extra destinations was that more people could see the Bell; many suspected those new stops were to help the Big Grizzly troll for votes.

**********

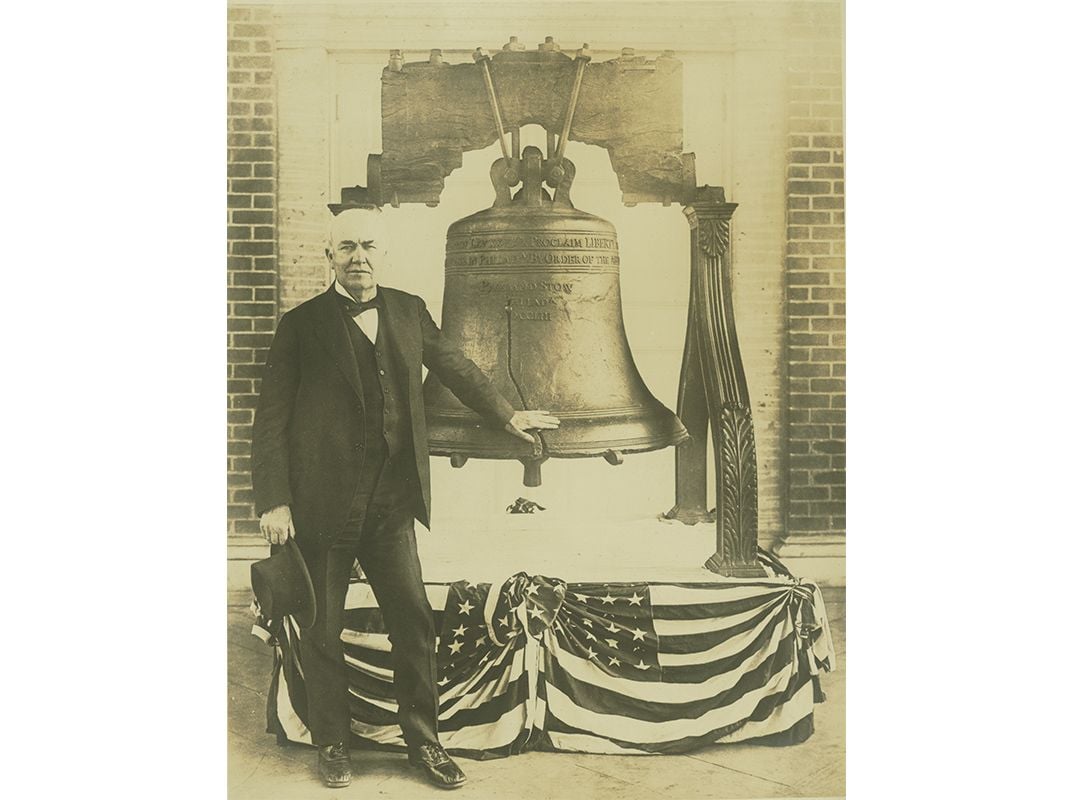

Ultimately, however, Penrose chose not to run. Instead, he focused on making sure Rudy Blankenburg was voted out of office and even tried to get him indicted. He succeeded only in getting one of his puppets, former postmaster Thomas Smith, elected mayor.

Thus Smith received the honor of sounding the Liberty Bell for the first war bond drive in June 1917. Smith got to walk heroically through the throng gathered at Independence Hall, ring the Bell to trigger the great national clangor, and be interviewed for the many stories the government’s war propaganda office set up. (The releases were full of overstatements, including the “fact” that the Bell hadn’t been rung in decades when, of course, it had been rung over the transcontinental phone line just two years earlier.) Americans rushed to their banks to buy up the war bonds, and sales far surpassed the $2 billion goal.

But by the time of the second Liberty Bond drive, in October 1917, Smith had other concerns: He had become the first sitting mayor in American history to be indicted for conspiracy to commit murder—in the street killing of a police officer who was trying to protect a progressive city council candidate from being beaten up by hired thugs. This took place in Philadelphia’s Fifth Ward, which included Independence Hall, and which was there-after known as “the Bloody Fifth.” Smith was brought to trial and acquitted.

When the Treasury Department decided to recreate its national bell-sounding for the second bond drive, it chose to trigger the clangor from a new location—St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, where Patrick Henry had delivered his “give me liberty or give me death” speech.

But by then, the Liberty Bell had become the dominant symbol of the war effort, and the sounding of bells (and whistles where there were no bells) became the Pavlovian cue to do the right thing—whether that meant buying war bonds, enlisting in the military or raising money for the Red Cross. Making a pilgrimage to see and kiss the Bell became a wartime fad. It began in 1917 when the top French general, Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre, visited Independence Hall. After standing reverently before the Bell, he moved closer, until he reached out to touch it and then kissed his hands. Finally, he just bent down and kissed the Bell directly.

After hearing about what their commander did, a group of French soldiers touring the United States arrived at Independence Hall to do the same thing. And soon American soldiers were coming in alone or with their units to kiss the Bell for luck before leaving for Europe.

So the Bell was taken on patriotic parades around Philadelphia, and it was rung again as part of the third and fourth Liberty Bond drives—with the nation’s bells rung once more in response. As a stunt for the fourth and last Liberty Bond drive, 25,000 troops at Fort Dix were herded into the shape of the Bell and photographed from above—and copies of the photo were distributed nationwide. For the last day of the final bond drive, in August of 1918, the Treasury Department arranged again for the Bell to be struck 13 times, but this time it triggered not a national bell-ringing but a simultaneous singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” across the land. The four drives raised more than $17 billion.

Just weeks before the war ended, in November 1918, the leaders of all the new Mid-European countries created by the war—representing some 65 million people—descended upon Philadelphia to sign their declaration of independence, led by Tomas Masaryk, soon to be the first president of a free Czechoslovakia. They arrived with a cast replica of the Liberty Bell, which they created to ring in the presence of the original.

The only difference was that, on their bell, the biblical quote had been changed to read, “Proclaim liberty throughout all the world.”

**********

On the morning of Thursday, November 7, more than a million people reportedly poured into the streets of Philadelphia, shredded paper rained from office windows, schools closed, tens of thousands of workers at the city’s Navy shipyards laid down their tools and ran to celebrate. Bells chimed, whistles shrieked, sirens moaned, planes flew low over the city. Mobs descended on Independence Hall, and the city ordered the new Independence Hall bell rung—along with every other bell in the city—and even had the Liberty Bell struck.

It was pandemonium in Philadelphia—and in every other city in the country, since word had gone out on the United Press International wire that the war was over. After so much celebrating, it was that much harder to convince everyone that the report was premature. Revelers across the country refused to accept the fact until they saw it in the newspaper the next morning.

At about 3:30 on the following Monday morning, however, word again began circulating that peace was at hand. Within an hour, every hotel room in Philadelphia was booked. When the usual morning bells and whistles and sirens were sounded—and then kept right on sounding—people understood it wasn’t a false alarm. They didn’t bother to go to work—they headed into town.

Most headed to Independence Hall, to be near the Bell and the nation’s birthplace. Many arrived with their shirt collars and sleeves loaded with confetti, which was carpeting the streets like an early snowfall.

So many people wanted to be in the presence of the Bell that the guards finally removed the turnstiles from the entrance to Independence Hall. The eldest of the guards, 80-year-old James Orr, who had been on duty at Independence Hall for more than 25 years, told his fellow officers just to give up.

Thousands of people kissed the Liberty Bell that day, more than ever had before and ever would again. A Philadelphia Inquirer reporter stood there taking in the scene, noting all the different nationalities of people who had come to kiss the Bell. But then he had an epiphany.

“Most of the throng,” he wrote, “had become so Americanized that it was difficult to tell the people of one race from those of another.”

Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West--One Meal at a Time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/d9/4cd975be-f91c-46e3-b08c-e51de8964e7a/apr2017_k24_libertybell-wr.jpg)