How Lincoln Bested Douglas in Their Famous Debates

The 1858 debates reframed America’s argument about slavery and transformed Lincoln into a presidential contender

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/facethenation_sept08_631.jpg)

In Freeport, Illinois, just beyond the somnolent downtown, a small park near the Pecatonica River is wedged next to the public library. In the mid-19th century, however, land along the shore stretched green into the distance, the grassy hills dotted with maples and river birches. It was here, on August 27, 1858, that U.S. senatorial candidates Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas waged a war of words.

"Imagine that you're there," says my guide, George Buss, stepping onto the four-foot-high concrete replica of a speaker's platform, installed here in 1992 to memorialize the debate. He places a hand on the head of the squat, life-size bronze sculpture of Douglas, who was a foot shorter than Lincoln. "Picture the banners, brass bands and parades...people pushing and shoving...kids running up to the comurthouse for sandwiches, where they're barbecuing an ox. Douglas is pacing back and forth like a lion. People in the back of the crowd are shouting, ‘What'd he say? What'd he say?'"

At 6-foot-5 and with craggy features, deep-set eyes and gangly limbs, Buss, a Freeport school administrator, bears an eerie resemblance to the 16th president. Indeed, for 22 years, Buss has moonlighted as one of the nation's most accomplished Lincoln interpreters. As a schoolboy nearly 40 years ago, he got hooked on Honest Abe when he learned that one of the seven historic Lincoln-Douglas debates had taken place in his hometown.

Buss continues: "Lincoln stretches up onto his toes to make a point." He recites Lincoln's words: "Can the people of a United States territory, in any lawful way, against the wish of any citizen of the United States, exclude slavery from its limits prior to the formation of a state constitution?" Looking into the distance, Buss repeats: "Just imagine that you're there."

Lincoln and incumbent senator Douglas squared off, of course, in the most famous debates in American history. The Illinois encounters would reshape the nation's bitter argument over slavery, transform Lincoln into a contender for the presidency two years later and set a standard for political discourse that has rarely been equaled. Today, the debates have achieved a mythic dimension, regarded as the ultimate exemplar of homegrown democracy, enacted by two larger-than-life political figures who brilliantly explicated the great issues of the day for gatherings of ordinary citizens.

Momentous issues were at stake. Would the vast western territories be opened to slavery? Would slavery insinuate itself into the states where it was now illegal? Had the founding fathers intended the nation to be half slave and half free? Did one group of states possess the right to dictate to another what was right and wrong? According to Tom Schwartz, Illinois' state historian, "each man was pretty plain in how he would deal with the major issue facing the nation: the expansion or elimination of slavery. These are still the gold standard of public discussion."

But while the debates have long been recognized as a benchmark in American political history, they are probably more celebrated than they are understood. It is indeed true that in the course of seven debates, two of the country's most skilled orators delivered memorably provocative, reasoned and (occasionally) morally elevated arguments on the most divisive issues of the day. What is less well-known, however, is that those debates also were characterized by substantial amounts of pandering, baseless accusation, outright racism and what we now call "spin." New research also suggests that Lincoln's powers of persuasion were far greater than historians previously realized. In our own day, as two dramatically different candidates for president clash across an ideological divide, the oratorical odyssey of Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas may offer more than a few lessons—in the power of persuasive rhetoric, the effect of bigotry and the American public's craving for political leaders who are able to explain the great issues of the day with clarity and conviction.

Both then and now, the debates' impact was amplified by changing technology. In 1858, innovation was turning what would otherwise have been a local contest into one followed from Mississippi to Maine. Stenographers trained in shorthand recorded the candidates' words. Halfway through each debate, runners were handed the stenographers' notes; they raced for the next train to Chicago, converting shorthand into text during the journey and producing a transcript ready to be typeset and telegraphed to the rest of the country as soon as it arrived. "The combination of shorthand, the telegraph and the railroad changed everything," says Allen C. Guelzo, author of Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America. "It was unprecedented. Lincoln and Douglas knew they were speaking to the whole nation. It was like JFK in 1960 coming to grips with the presence of the vast new television audience."

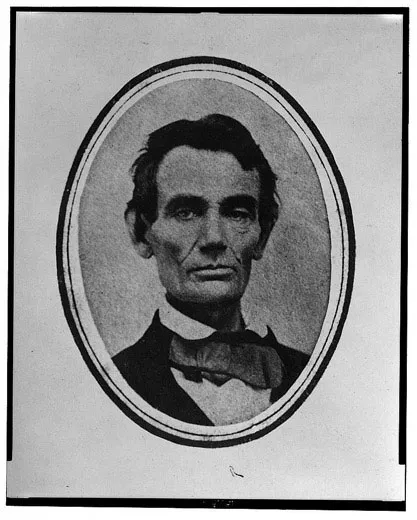

At the time, Lincoln was not the haggard, hollow-eyed figure of his Civil War photographs. At 49, he was still cleanshaven, with chiseled cheekbones and a faint smile that hinted at his irrepressible wit. And while he affected a backwoods folksiness that put voters at ease, he was actually a prosperous lawyer who enjoyed an upper-middle-class existence in an exclusive section of Springfield, the state capital. "Lincoln was always aware of his image," says Matthew Pinsker, a Lincoln scholar based at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. "He deliberately emphasized his height by wearing a top hat, which made him seem even taller. He knew that it made him stand out."

For Lincoln, the Republican senatorial nomination was a debt repaid; four years before, he had withdrawn from the contest for Illinois' other U.S. Senate seat, making way for party regular Lyman Trumbull. "The party felt that it had an obligation to him, but few believed that he could actually beat Douglas," says Guelzo. To Lincoln's chagrin, some Republican power brokers—including New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley—actually favored Douglas, whom they hoped to recruit as a Republican presidential candidate in 1860.

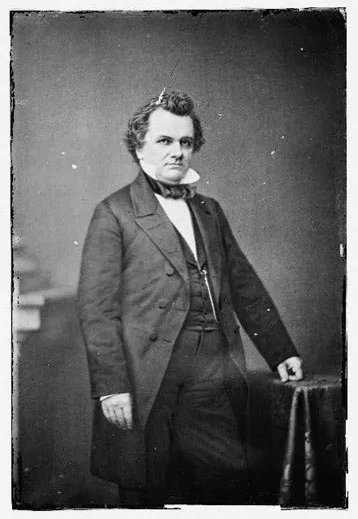

In contrast to the moody and cerebral Lincoln, Douglas was gregarious and ingratiating, with a gift for making every voter feel that he was speaking directly to him. "Douglas was a pure political animal," says James L. Huston, author of Stephen A. Douglas and the Dilemmas of Democratic Equality. "For him, the will of the majority was everything. He tells voters, ‘Whatever you want, gentlemen, that's what I'm for!'" In spite of poor health, he possessed such volcanic energy that he was known as "a steam engine in breeches." Within three years of arriving in Illinois from his native Vermont, in 1833, he won election to the state legislature. Four years after that, at 27, he was appointed to the State Supreme Court, and at 33 to the U.S. Senate. (In 1852, Lincoln, who had served a single undistinguished term in Congress, jealously complained, "Time was when I was in his way some; but he has outgrown me & [be]strides the world; & such small men as I am, can hardly be considered worthy of his notice; & I may have to dodge and get between his legs.")

On the great issue of their time, the two men could not have been more diametrically opposed. Although Douglas professed a dislike of slavery, his first wife, Martha, who died in 1853, had owned some

slaves in Mississippi—a fact he did not publicize. During the marriage, the sweat of slaves had provided the natty outfits and luxury travel that he relished. What Lincoln detested about slavery was not only the degradation of African-Americans but also the broader tyranny of social hierarchy and economic stagnation that the practice threatened to extend across America. But like many Northerners, he preferred gradual emancipation and the compensation of slave owners for their lost property to immediate abolition. "For Lincoln, slavery is the problem," says Guelzo. "For Douglas, it's the controversy about slavery that's the problem. Douglas' goal is not to put an end to slavery, but to put an end to the controversy."

For most of the 1850s, Douglas had performed a political high-wire act, striving to please his Northern supporters without alienating Southerners whose backing he would need for his expected run for the presidency in 1860. He finessed the looming slavery question by trumpeting the doctrine of "popular sovereignty," which asserted that settlers in any new territory had the right to decide for themselves whether it should be admitted to the union as a slave or free state. In 1854, Douglas had incensed Yankees by pushing the Kansas-Nebraska Act through Congress as popular sovereignty; it opened those territories to slavery, at least in principle. Nearly four years later, he angered Southerners by opposing the pro-slavery Kansas state constitution that President James Buchanan supported. As he prepared to face Lincoln, Douglas didn't want to offend the South any further.

Although we regard the debates today as a head-to-head contest for votes, in fact neither Lincoln nor Douglas was on the ballot. U.S. senators were chosen by state legislatures, as they would be until 1913. That meant that the party holding the most seats in the state legislature could choose who to send to the Senate. Even this was not as straightforward as it seemed. The sizes of districts varied wildly as a result of gerrymandering, in Illinois' case by Democrats, who dominated state politics. In some Republican-leaning districts, for instance, it took almost twice as many votes to elect a legislator as in pro-Democratic districts. "Southern Illinois was Southern in outlook, and many people there sympathized with slavery," says historian Schwartz. "Northern Illinois was abolitionist. The middle section of the state, heavily populated by members of the old Whig Party, was politically fluid. Lincoln's challenge was to bring that middle belt over to the Republicans."

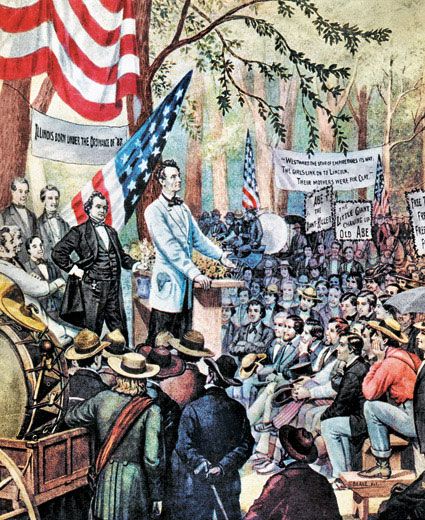

Each debate was to be three hours long. The candidates would address each other directly. The first speaker would deliver an hourlong opening statement; the second would then have the floor for an hour and a half. The first speaker would then return to the podium for a half-hour rebuttal. There were no restrictions on what they could say. Never before had an incumbent senator, much less one of Douglas' stature, agreed to debate his challenger in public. (Douglas assumed that his renowned oratorical powers would defeat Lincoln handily.) Excitement ran high. Tens of thousands of men, women and children flocked to the debates, which—in an age before television, national teams or mass entertainment—took on the atmosphere of a championship prizefight and county fair combined. "We were fed on politics in those days, and my twin sister and I would not have missed the debate for all the things in the world," Harriet Middour, an Illinois housewife who had attended the Freeport debate as a girl, would recall in 1922. Lincoln, whose campaign funds were limited, traveled modestly by coach. Douglas rolled along in style, ensconced in his own private railway car, trailed by a flatcar fitted with a cannon dubbed "Little Doug," which fired off a round whenever the train approached a town.

The two antagonists met first on August 21, 1858, in Ottawa, 50 miles west of Chicago. Douglas sneered that Lincoln was no more than a closet abolitionist—an insult akin to calling a politician soft on terrorism today. Lincoln, he went on, had wanted to allow blacks "to vote on an equality with yourselves, and to make them eligible to [sic] office, to serve on juries, and to adjudge your rights." Lincoln appeared stiff and awkward and failed to marshal his arguments effectively. The pro-Douglas State Register crowed, "The excoriation of Lincoln was so severe that the Republicans hung their heads in shame."

Six days later at Freeport, Douglas still managed to keep Lincoln largely on the defensive. But Lincoln set a trap for Douglas. He demanded to know whether, in Douglas' opinion, the doctrine known as popular sovereignty would permit settlers to exclude slavery from a new territory before it became a state. If Douglas answered "no," that settlers had no right to decide against slavery, then it would be obvious that popular sovereignty would be powerless to stop westward expansion of bondage, as Douglas sometimes implied that it could. If Douglas answered "yes," that the doctrine permitted settlers to exclude slavery, then he would further alienate Southern voters. "Lincoln's goal was to convince voters that popular sovereignty was a sham," says Guelzo. "He wanted to make clear that Douglas' attitude toward slavery would inevitably lead to more slave states—with more slave-state senators and congressmen, and deeper permanent entrenchment of the slave power in Washington." Douglas took Lincoln's bait: "Yes," he replied, popular sovereignty would allow settlers to exclude slavery from new territories. Southerners had suspected Douglas of waffling on the issue. Their fear was now confirmed: two years later, his answer would come back to haunt him.

The debaters met for the third time on September 15 at Jonesboro, in a part of southern Illinois known as "Egypt" for its proximity to the city of Cairo. Once again, Douglas harangued Lincoln for his alleged abolitionism. "I hold that this government was made on the white basis, by white men, for the benefit of white men and their posterity forever, and should be administered by white men and none others," he fulminated. He warned that Lincoln would not only grant citizenship and the right to vote to freed slaves but would allow black men to marry white women—the ultimate horror to many voters, North and South. Douglas' racial demagoguery was steadily taking a toll. Lincoln's backers feared that not only would Lincoln lose the election, but that he would bring down other Republican candidates. Finally, Lincoln counter-attacked.

At Charleston, three days later, Lincoln played his own race card. The debate site—now a grassy field between a trailer park and a sprawl of open sheds where livestock is exhibited at the county fair—lies only a few miles north of the log cabin where Lincoln's beloved stepmother, Sarah, still lived. On that September afternoon, Lincoln declared that while he opposed slavery, he was not for unequivocal racial equality. "I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people," Lincoln now asserted, "and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race."

Ugly though it was, Charleston would prove to be the debates' turning point. Until that moment, Lincoln had been on the defensive. But a shift in public perception was underway. "People suddenly realized that something extraordinary was going on, that Douglas had failed to vanquish Lincoln," says Guelzo. "From now on, Lincoln was like Rocky Balboa."

The debaters' next venue was Knox College in the western Illinois town of Galesburg, a bastion of evangelical religion and abolitionism. On the day of the debate, October 7, torrential rains and gusting winds sent campaign signs skittering and forced debate organizers to move the speakers' platform, sheltering it against the outside wall of the neo-Gothic Old Main hall. The platform was so high, however, that the two candidates had to climb through the building's second-floor windows and then down a ladder to the stage. Lincoln drew a laugh when he remarked, "At last I can say now that I've gone through college!"

"It took Lincoln several debates to figure out how to get on the offensive," says Douglas L. Wilson, co-director of the Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College. "Unlike Douglas, who always said the same things, Lincoln was always looking for a new angle to use. Rather, Lincoln's strategy was about impact and momentum. He knew that at Galesburg he'd have a good chance to sway hearts and minds."

The atmosphere was raucous. Banners proclaimed: "Douglas the Dead Dog—Lincoln the Living Lion," and "Greasy Mechanics for A. Lincoln." Estimates of the crowd ranged up to 25,000.

When Lincoln stepped forward, he seemed a man transformed. His high tenor voice rang out "as clear as a bell," one listener recalled. Without repudiating his own crude remarks at Charleston, he challenged Douglas' racism on moral grounds. "I suppose that the real difference between Judge Douglas and his friends, and the Republicans on the contrary, is that the Judge is not in favor of making any difference between slavery and liberty...and consequently every sentiment he utters discards the idea that there is any wrong in slavery," Lincoln said. "Judge Douglas declares that if any community want slavery, they have a right to have it. He can say that, logically, if he says that there is no wrong in slavery; but if you admit that there is a wrong in it, he cannot logically say that anybody has a right to do wrong." In the judgment of most observers, Lincoln won the Galesburg debate on all points. The pro-Lincoln Chicago Press and Tribune reported: "Mr. Douglas, pierced to the very vitals by the barbed harpoons which Lincoln hurls at him, goes around and around, making the water foam, filling the air with roars of rage and pain, spouting torrents of blood, and striking out fiercely but vainly at his assailant."

Six days later, the debaters clashed again at the Mississippi River port of Quincy, 85 miles southwest of Galesburg. "The debate was the biggest thing that ever happened here," says Chuck Scholz, the town's former mayor and a history buff. Scholz, who led Quincy's urban renewal in the 1990s, stands in Washington Square, the site of the debate, among cherry and magnolia trees in glorious bloom. "From where they stood that afternoon, the choice facing voters was pretty stark," says Scholz. "Here they were on the free soil of Illinois. Within sight across the river lay the slave state of Missouri."

Lincoln came on aggressively, building on the same argument he had launched the week before. Although the Negro could not expect absolute social and political equality, he still enjoyed the same right to the freedoms of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness that were promised to all by the Declaration of Independence. "In the right to eat the bread without the leave of anybody else which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every other man," Lincoln declared. Douglas, ill with bronchitis, seemed sluggish and unsteady. He accused Lincoln of promoting mob violence, rebellion and even genocide by confining slavery only to the states where it already existed. Without room for slavery to expand, the natural increase of the slave population would lead to catastrophe, Douglas claimed. "He will hem them in until starvation seizes them, and by starving them to death, he will put slavery in the course of ultimate extinction," Douglas went on. "This is the humane and Christian remedy that he proposes for the great crime of slavery." The pro-Lincoln Quincy Daily Whig reported that Lincoln had given Douglas "one of the severest skinnings he has received."

The next day, the two men walked down to the Mississippi River, boarded a riverboat and steamed south to the port of Alton for their seventh and final debate. Today, Alton's seedy riverfront is dominated by towering concrete grain elevators and a garish riverboat casino, the Argosy, the city's main employer. "If it wasn't for that boat, this city would be in dire straits," says Don Huber, Alton's township supervisor. "This is the Rust Belt here."

On October 15, the weary gladiators—they had been debating for seven weeks now, not to mention speaking at hundreds of crossroads and whistle-stops across the state—gazed out over busy docks piled high with bales and crates; riverboats belching smoke; and the mile-wide Mississippi. Here, Lincoln hoped to administer a coup de grace. "Lincoln was vibrant," says Huber. "Douglas was liquored up and near the point of collapse." (He was known to have a drinking problem.) His voice was weak; his words came out in barks. "Every tone came forth enveloped in an echo—you heard the voice but caught no meaning," reported an eyewitness.

Lincoln hammered away at the basic immorality of slavery. "It should be treated as a wrong, and one of the methods of...treating it as a wrong is to make provision that it shall grow no larger," he declared, his high-pitched voice growing shrill. Nothing else had ever so threatened Americans' liberty and prosperity as slavery, he said. "If this is true, how do you propose to improve the condition of things by enlarging slavery—by spreading it out and making it bigger?" He then went on to the climax of the argument that he had been building since Galesburg: "It is the same spirit that says, ‘You work and toil and earn bread, and I'll eat it.' No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle."

Lincoln's appeal to higher morality towered over Douglas' personal attacks. "Everyone knew that Lincoln had turned in a stellar performance, and that he had bested Douglas," says Guelzo. "He managed not only to hold his own, but when they got to the end, Lincoln was swinging harder than ever."

Still, our perception of the debates is skewed by our admiration for Lincoln. "We are all abolitionists today—in Lincoln's arguments we can see ourselves," says Douglas biographer James Huston. "We sympathize with his perception of the immorality of slavery. Lincoln is speaking to the future, to the better angels of our own nature, while Douglas was speaking in large part to the past, in which slavery still seemed reasonable and defensible."

But while Lincoln may have won the debates, he lost the election. The "Whig Belt" went almost entirely for Douglas and the new legislature would re-elect Douglas 54 percent to 46 percent. Recent research by Guelzo tells a surprising story, however. By analyzing the returns district by district, Guelzo discovered that of the total votes cast for House seats, 190,468 were cast for Republicans, against 166,374 for Democrats. In other words, had the candidates been competing for the popular vote, Lincoln would have scored a smashing victory. "Had the districts been fairly apportioned according to population," says Guelzo, "Lincoln would have beaten Douglas black and blue." If the election was a triumph for anything, it was for gerrymandering.

Still, the debates introduced Lincoln to a national audience and set the stage for his dark-horse run for the Republican presidential nomination two years later. "Lincoln comes out of the debates a more prominent figure in Illinois and across the country," says historian Matthew Pinsker. "The key question facing him before the debates was: Can he lead a party? Now he has the answer: He can. He now begins to see himself as a possible president." Douglas had won re-election to the Senate, but his political prospects had been fatally wounded. In 1860, he would fulfill his ambition of winning the Democratic nomination for president, but in the general election he would win only one state—Missouri.

In the debates of 1858, Lincoln had also finally forced the coruscating issue of slavery out into the open. Despite his own remarks at Charleston, he managed to rise above the conventional racism of his time to prod Americans to think more deeply about both race and human rights. "Lincoln had nothing to gain by referring to rights for blacks," says Guelzo. "He was handing Douglas a club to beat him with. He didn't have to please the abolitionists, because they had nowhere else to go. He really believed that there was a moral line that no amount of popular sovereignty could cross."

Says Freeport's George Buss: "We can still learn from the debates. They're not a closed book."

Writer Fergus M. Bordewich's most recent book is Washington: The Making of the American Capital.