How New York City Found Clean Water

For nearly 200 years after the founding of New York, the city struggled to establish a clean source of fresh water

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/0f/190f02d3-9863-48f8-9d2a-51cc2e262832/gettyimages-1054375422.jpg)

Centuries before New York City sprawled into a skyscraping, five-borough metropolis, the island of Manhattan was a swampy woodland. Ponds and creeks flowed around hills and between trees, sustaining nomadic Native Americans and wildlife. But after the Dutch established a colony in 1624, water shortages and pollution began threatening the island’s natural supply, sparking a crisis that would challenge the livability of Manhattan for 200 years.

Water, Water Everywhere, and Not a Drop to Drink

The town of New Amsterdam, Manhattan’s original colonial settlement, was built on the swampiest part of the island: its southern shore. The closest fresh water sources were underground, but none of it was very fresh. Salt waters surrounding the island brined New Amsterdam’s natural aquifers and springs. A defensive wall built in 1653 cut the colony off from better water to the north. The Dutch dug shallow wells into the available brackish water, and built cisterns to collect rain, but neither source was enough to satisfy the colony’s needs: brewing warm beer, feeding goats and pigs, cooking, firefighting and manufacturing. The water could rarely be used for drinking, according to historian Gerard Koeppel, author of Water for Gotham. “It was loaded with all kinds of particulate matter that made the water unsatisfying as a drinking experience,” he says.

By 1664, New Amsterdam’s limited, salty supply of water, along with a shoddy wooden fort, left the Dutch dehydrated and virtually defenseless, allowing the English to take over without a fight and rename the land New York.

The English maintained many of the colony’s existing customs, particularly its sanitation methods, or lack thereof. From the rowdy seaport to the renovated fort, the colonists ran amok in noxious habits. Runoff from tanneries, where animal skins were turned into leather, flowed into the waters that supplied the shallow wells. Settlers hurled carcasses and loaded chamber pots into the street. The goats and pigs roamed free, leaving piles of droppings in their tracks. In early New York, the streets stank.

The smell, however, did not deter newcomers. Three decades after the founding of New York, the population more than doubled, reaching 5,000. The English demolished the old Dutch wall, which became today’s Wall Street, and the colony expanded north. The colonists shared a dozen wells dug into the garbage-infested streets. According to Koeppel, a law ordering all “Tubs of Dung” and other “Nastiness” to be dumped only into the rivers was passed, but the local colonial government hardly enforced it—making New York the perfect breeding ground for mosquitos. Yellow fever struck in 1702, killing 12 percent of the population, and was followed by smallpox, measles and more yellow fever through 1743.

An incredulous scientist named Cadwallader Colden observed in an essay on the pungent city that the colonists would rather “risk their own health and even the destruction of the whole community” than clean up after themselves. Wealthy colonists bought carted water from an untainted pond just north of the city, named Collect Pond. But another law passed by the city’s Common Council forced all tanneries to relocate, and they moved to the worst place possible—the banks of Collect Pond.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/7d/747dda02-defd-4cff-b37b-1d61c48099e1/hb_5490168.jpg)

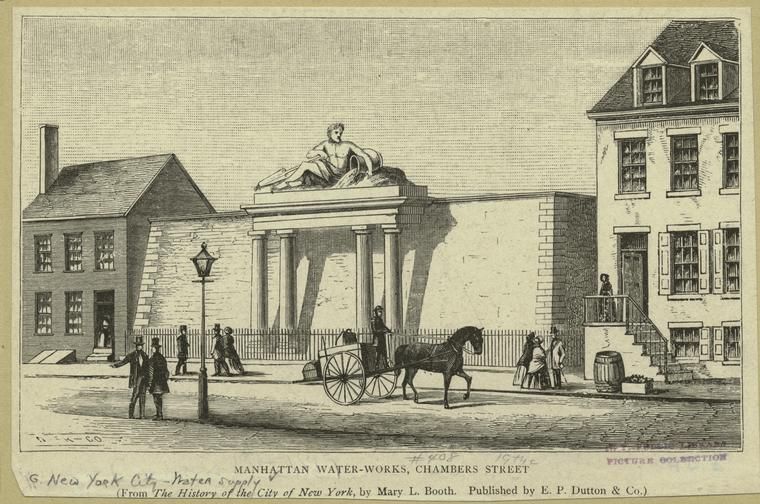

In 1774, a fortune-seeking engineer named Christopher Colles proposed an idea to bring “a constant supply” of fresh water to the city with a population approaching 25,000. It was a novel concept for the colonial era: pine piping under every street, with pumps placed every 100 yards. A 1.2-million-gallon masonry reservoir, pulling from a 30-foot-wide, 28-foot-deep well dug beside Collect Pond, would supply the pipes.

To raise the water from well to reservoir, Colles built a steam engine—the second ever made in America, according to Koeppel—with scant resources. The engine could pump 300,000 gallons per day into the reservoir, enough to supply every citizen with 12 gallons per day—if only the waterworks had reached completion.

In 1776, a year after the outbreak of the American Revolution, British forces occupied New York, spurring about 80 percent of the population to flee, including Colles. Sanitation deteriorated even further. Collect Pond became a town dump. In 1785, an anonymous writer in the New York Journal observed people “washing … things too nauseous to mention; all their sudds and filth are emptied into this pond, besides dead dogs, cats, etc. thrown in daily, and no doubt, many buckets [of excrement] from that quarter of the town.”

After the war, a community-endorsed petition urged the Common Council to continue Colles’ project, according to Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 by New York historians Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, but the city lacked the funds. Yellow fever returned in the 1790s and the coffin business boomed. Nonetheless, the city continued expanding. Streets were paved around Collect Pond, and the Common Council searched for a new way to supply water to the city. The water problem piqued the interest of a New York State assemblyman: Aaron Burr.

The Great Water Hoax

In 1798, Joseph Browne, a doctor from Westchester County, proposed to the Common Council that New York City find a water source beyond Manhattan. Development, he contended, would continue polluting local waters. Knowing the city was financially strapped, he suggested that only a private company could fund the complex project. Browne also happened to be Burr’s brother-in-law.

Manhattan’s State Assembly delegation met to debate “an act for supplying the city of New-York with pure and wholesome water.” Burr argued for a private company to build the infrastructure, while most of his colleagues dissented. So Burr requested and was granted a ten-day leave to assess the city leaders’ preference.

In New York’s water crisis, Burr saw an opportunity. He planned to create the water company himself, and, somehow, use its income to establish a bank to rival Alexander Hamilton’s Bank of New York. And the best part? He’d trick his famous Federalist nemesis, then a lawyer, into helping him.

The Democratic-Republican Burr set up a meeting with Federalist mayor Richard Varick, Hamilton and a group of city merchants. According to records kept by U.S. Senator Philip Schuyler, Burr persuaded them that watering Manhattan—a cause far more important than political quibbles—could only be achieved by private investment. Days later, the Common Council, dominated by Federalists, were convinced by a letter from Hamilton to support Burr's plan.

Burr returned to the State Assembly to report the city’s preference for a private waterworks company. Burr reviewed a draft of the Assembly’s bill with a small committee, and he added a clause that would allow the company to use “surplus capital” for any business purposes beyond the waterworks. This was a completely new freedom for an American company. “In those days, private companies weren’t incorporated by the state legislature,” Koeppel says. “They were always incorporated for a singular purpose—not to do general business.”

No assemblymen contested the clause on record. The waterworks bill passed and moved on to the State Senate, which ratified the law in April 1799. By September, Burr, Browne, and a group of wealthy citizens established the Manhattan Company as both a bank and a waterworks committed, supposedly, to finding a water source outside the city and ending yellow fever.

“Browne proposed the Bronx River, and no sooner do they get incorporated do they abandon this idea,” Koeppel says. The Manhattan Company’s leadership decided the Bronx River—a waterway that divided New York City from the future Bronx borough—was too far away to be profitable. To save money and time, the company built its waterworks near a pond within the city: Collect Pond. Curiously, Browne—the company’s superintendent—no longer publicly contended that the pond was filthy. The company even sought and gained the approval of Colles, who had become a surveyor, for its plan: a steam-powered waterworks with wooden piping, much like his own proposal from the 1770s.

By 1802, the Manhattan Company’s waterworks was running with 21 miles of leaky wooden pipes. According to Diane Galusha’s book Liquid Assets: A History of New York City’s Water System, customers spoke frequently of the water’s undrinkability and unavailability. Tree roots pierced the pipes, and repairs took weeks. The next year, yellow fever killed 600, a number that rose to 1,000 by 1805, when 27,000 fled from a city of 75,000, according to city records cited by Koeppel.

From 1804 to 1814, the city battled an average of 20 fires each year, hamstrung by its limited waterworks. Nothing could be done to oust Burr’s Manhattan Company, the ostensible savior of the city’s water supply, as it was fulfilling its mandate of providing an eventual 691,200 gallons per day. During this time, Burr would become vice president of the United States, kill Hamilton in a duel, and be tried for treason after allegedly attempting to create a new empire—all while the bank he created thrived.

Through the 1820s, the city continued its struggle to find a potable water source. Surveyors scouted rivers and ponds north of Manhattan, but the rights to nearly every nearby water source belonged to a canal company or the Manhattan Company. “If New York City did not have a source of fresh drinking water, it would dry up, literally and figuratively,” Galusha says.

To solve its water problem, city leaders had to think boldly.

A Final Straw

Perhaps no disease tested New Yorkers’ spirit more than the Asiatic cholera outbreak of 1832. In July alone, 2,000 New Yorkers died from a mysterious infectious bacteria. More than 80,000 people, about a third of the city at the time, fled for their lives. Around 3,500 cholera deaths were recorded that year, and some who fled succumbed to the disease, too. Doctors would learn its source two decades later, when a British physician discovered that the bacteria spread through water systems.

The treasurer of the city’s Board of Health, Myndert Van Schaick, advocated a lofty proposal. It wasn’t a new proposal—the idea had been floated in the Common Council’s chambers before—but it was always dismissed as being too costly and too far away. He suggested the city shift its water source to the Croton River, 40 miles north.

“Ambitious wouldn’t even begin to describe it,” Galusha says. “Forty miles in horse and buggy days was a very long way.”

A young civil engineer named De Witt Clinton, Jr. surveyed the Croton River and found it unlike any waterway around New York City. The river was fresh, clean and vast. Surrounded by rough terrain, development could never encroach its waters. An aqueduct would have to bring the water to Manhattan by navigating hills, rivers and valleys over a distance never before reached by an American waterworks. Van Schaick, elected to the State Senate in 1833, facilitated a bill that established a Croton Water Commission to oversee the project.

Major David Bates Douglass, a civil and military engineer, came up with a plan: a masonry conduit would cut right through the hills, keeping the entire aqueduct on an incline so the water could flow by the power of gravity. For the Croton’s entrance across the Harlem River and into Manhattan, Douglass imagined a grand arched bridge echoing the aqueducts of ancient Rome, and multiple reservoirs connected by iron pipes underground.

At the next election three weeks later, in April 1835, the ballots would ask voters to decide on the Croton Aqueduct: “Yes” or “No.”

Pamphlets, distributed by landowners in the aqueduct’s potential path and by entrepreneurs aspiring to build their own waterworks, urged voters to say no. “It was difficult to conceive for many people, this idea that a city could bring water from a very remote source,” Koeppel says.

But the newspapers, understanding the importance of the project, argued that a better quality of life was worth a prospective tax increase. And the cholera epidemic was still fresh in everyone’s minds. A snowstorm resulted in a low turnout, but 17,330 yeses and 5,963 noes would forever change the future of the city.

One More Lesson

Eight months after the vote to construct the Croton Aqueduct, the ineptitude and corruption that characterized New York City’s water woes climaxed in a devastating evening.

On December 16, 1835, storms had left Manhattan’s streets covered in snow. The temperature dipped below 0 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Burrows and Wallace. Waters in the cisterns, street pumps and even the East River froze—all before a warehouse caught fire.

Chilling winds carried the flames from building to building. People ran into the streets to escape. Metal roofs melted and structures burned to rubble as the fire spread. Firemen watched almost helplessly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/5b/435b10a7-9351-4213-8da0-77a470e1834b/great_fire.jpg)

Marines from the Brooklyn Navy Yard across the East River rowed through the ice with barrels of gunpowder. The only way to stop the fire was to remove the next building in its path. Across Wall Street, the marines blew up several structures.

When the Great Fire of 1835 ended, nearly 700 buildings were destroyed—incredibly, only two people died.

As rebuilding efforts began, the Croton Water Commission fired Douglass after the engineer repeatedly pushed for more staff, struggled to meet deadlines and argued with the commissioners. They hired a man who had spent years building the Erie Canal, a self-taught civil engineer named John B. Jervis.

Building the Aqueduct

The first thing Jervis noticed as chief engineer was how much work remained. Douglass had not finalized the route, determined the aqueduct incline, or designed the dam and Harlem River bridge.

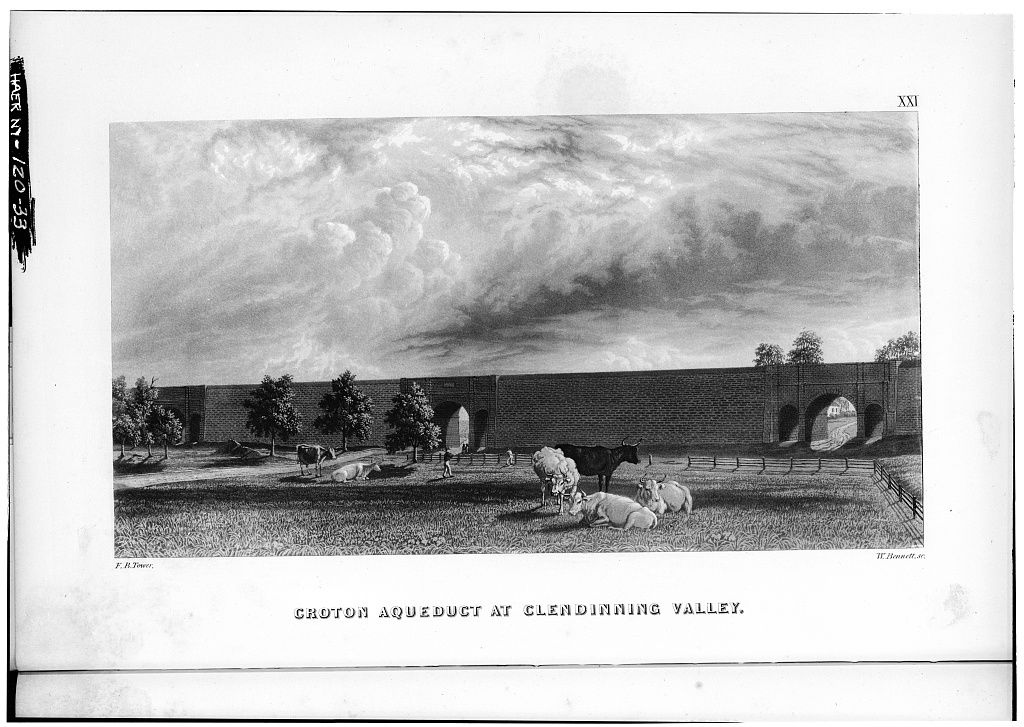

Jervis settled on a 41-mile path that would end at two reservoirs in Manhattan. The aqueduct would start at a 55-foot-tall masonry dam that would raise the river 40 feet. From there, water would flow down to the city at an incline of 13 inches per mile—a slope that could deliver 60 million gallons per day.

Robert Kornfeld, Jr., a principal at the engineering firm Thornton Tomasetti and vice president of Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct, a nonprofit preservation group, has spent years studying the historic waterworks. “It was unlike anything that had been built in the U.S. at that point,” he says.

The conduit itself was mostly a masonry tunnel, kept steady on its incline by running partially buried, traveling through hills and spanning across valleys. For its entry into Manhattan, the aqueduct crossed the Harlem River on an arched, Romanesque Revival stone bridge—all as Douglass had imagined.

The Harlem High Bridge stretched 1,420 feet long, supported by piles driven up to 45 feet into the riverbed. Eight arches spanned the river and another seven continued over land. Croton water flowed through iron pipes hidden beneath a walkway.

But the High Bridge took a decade to build. Everything else was completed by 1842, including a temporary embankment across the Harlem River that allowed the aqueduct to begin operation.

On June 27, 1842, Croton water reached Manhattan. Thousands of hydrants were placed on the streets in the next few years to provide free water for drinking and firefighting. The thankful city held a celebration in October 1842. Church bells rang, cannons fired at the Battery, and a parade marched up today’s Canyon of Heroes.

A Waterworks for the 20th and 21st Centuries

Innovation continued in the years after the Croton Aqueduct’s full completion in 1848. When cholera emerged again in 1849, the city responded by building its sewer system—enabling the creation of bathrooms with running Croton water.

The population skyrocketed. By the 1880s, the city exceeded one million, and suddenly the aqueduct could not meet demand. A new, much larger waterworks—the New Croton Aqueduct—opened in the 1890s and raised the water above the old Croton dam, which remains submerged to this day.

That same decade, one of the original reservoirs was demolished to make way for the New York Public Library’s Main Branch. In 1898, the Bronx, Staten Island, Queens, Brooklyn and Manhattan voted to unite as one City of New York. The union immediately brought the city’s population up to 3.3 million and prompted the construction of the Catskill and Delaware Aqueducts that are now world renowned for their quality. The New Croton Aqueduct now accounts for only about three percent of the city’s water.

In the 1930s, the Old Croton Aqueduct’s remaining reservoir was filled and buried under what is now Central Park’s Great Lawn. The old aqueduct began to gradually shut down in 1955. That same year, the Manhattan Company merged with another large financial institution to form Chase Bank.

Today, the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation oversees 26.2 miles of Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park, which runs from the Bronx to Cortlandt, New York. “A lot of the elements are still there,” Kornfeld says. “In addition to being a great civil engineering work, it’s a great work of landscape architecture, and that’s why it’s a great walking trail.”

Of the old aqueduct, only the High Bridge remains intact in city limits. In the 1920s, its river-spanning stone arches were replaced by one long steel archway, opening a path for large boats to pass underneath. It is the oldest bridge in the city, and the most tangible link to the waterworks that made New York City a populous, thriving metropolis.

Editor’s Note, November 26, 2019: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Harlem High Bridge was 1,420 feet tall, when, in fact it was 1,420 feet long. The story has been edited to correct that fact.