How New York Separated Immigrant Families in the Smallpox Outbreak of 1901

Vaccinations were administered by police raids, parents and children were torn apart, and the New York City Health Department controlled the narrative

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/e0/c9e04bfc-e5f8-49bd-bb58-62e90a9dad45/3b45199v.jpg)

Late on a Friday night in February 1901, when the residents of an Italian neighborhood in New York City’s East Harlem were home and sleeping, a battalion of more than 200 men—police officers and doctors—quietly occupied the roofs, backyards and front doors of every building for blocks. Under the command of the Bureau of Contagious Diseases, they entered the homes one by one, woke every tenant, scraped a patch of their skin raw with a lancet, and rubbed the wound with a small dose of the virus variola.

It was a smallpox raid, and the residents in good health were being vaccinated. But for anyone who showed any symptom of smallpox, the events of that night were even more alarming: They were taken immediately to docks on the East River, and sent by boat under the cover of night to an island just south of the Bronx: North Brother.

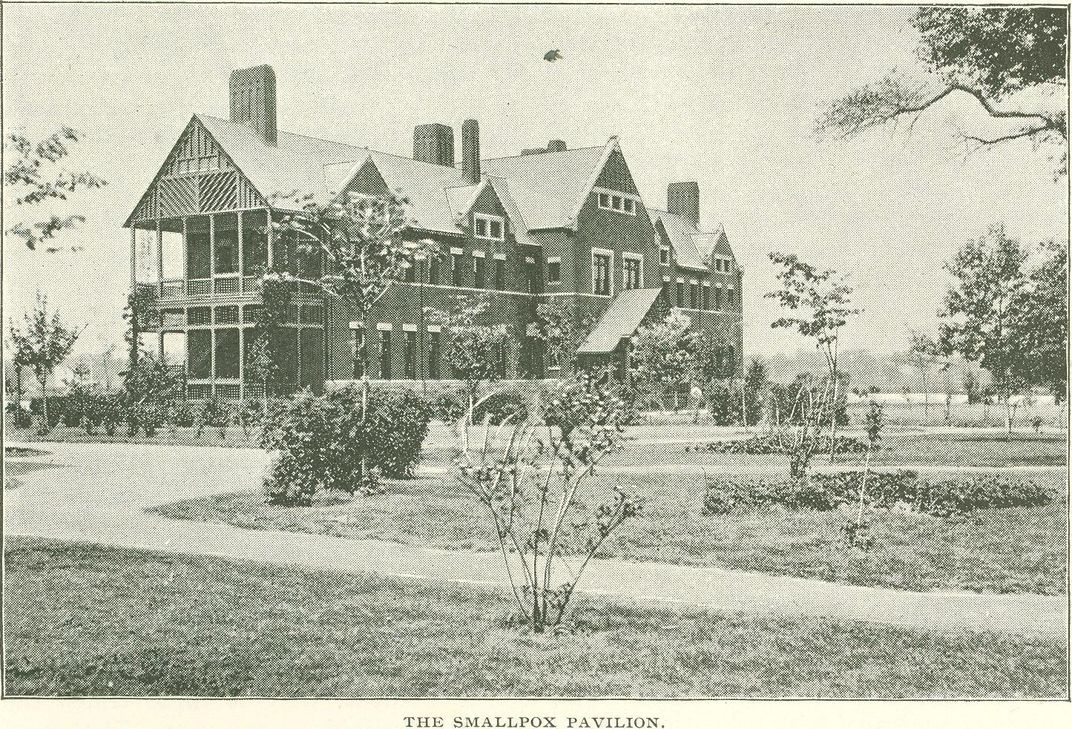

Today, North Brother Island is an overgrown and uninhabited bird sanctuary; from the 1880s to the 1940s, it was a thriving complex of quarantine hospitals for typhoid, smallpox, tuberculosis, diphtheria and other contagious illnesses. As of 1901, as the Atlanta Constitution reported, mere mention of the place to a New Yorker was “like conjuring up a bugaboo.”

On the night of the raid in East Harlem, doctors kicked down the padlocked door of an apartment belonging to an Italian immigrant family: the Caballos. Two children, both feverish, were hidden inside, under a bed. Their mother fought to keep hold of them as police and doctors carried them out of the apartment. “She fought like a tigress on the sidewalk,” the New York Times reported the next morning, “and her screams aroused the neighborhood for blocks around. Her babies were at last torn from her, and she was driven up the stairs to her desolate home to weep the night away.” Her name was not reported. The son who was taken from her, Molina, was four years old; her daughter Rosa, just two months.

The Caballos were two of eight children not older than six who were removed from their parents to North Brother Island that night, and two of 38 from that Upper East Side Italian neighborhood in that February week alone. When chief inspector Alonzo Blauvelt’s troops came through, they found babies hidden in cupboards, closets and under furniture. “In some cases,” the Times reported of a similar event in the same neighborhood two days earlier, “fathers took their children under their arms and fled with them over the roofs of houses to prevent them from being taken.”

In the end, parents were forced to stay behind, letting go of their ailing children without knowing if they would ever see them again. Some did not.

*********

The United States diagnosed its last case of smallpox in 1949, and by 1980, the disease was declared eradicated worldwide. But prior to that, smallpox killed 300 million people around the globe. From late 1900 through 1902, American newspapers reported outbreaks from Boston to San Francisco, and health departments struggled to contain the virus and mitigate its spread. Across the country, individuals were barred from appearing in public under any condition if smallpox had struck their household. Almena, Kansas, shut down schools. In Delaware County, Indiana, officials placed whole towns under quarantine. In Berkeley, California, children at a residential school where smallpox cases were reported had their hair shorn and were bathed in alcohol. (This made local news when one child was accidentally immolated by an attendant who was careless in disposing of a lit cigarette.)

Often, marginalized communities were called out by governments and the media as threats: In Bemidji, Minnesota, the Bemidji Pioneer reported the Ojibwe tribe of the Mille Lacs reservation were “menacing the nearby white settlements” with their smallpox fatalities. In Buffalo, New York, the Buffalo Courier blamed the “carelessness” of the low-income Polish district for the disease’s spread. In New York City, Italians were shamed by public health officials: “No one knows the harm that has been done by these Italians,” Manhattan sanitation superintendent Frederick Dillingham told the New York Times during the February raids. “They have gone from infected homes to work everywhere; they have ridden in street cars, mingled with people, and may have spread the contagion broadcast.”

Contending with outbreaks of smallpox and other contagious diseases in the teeming 19th-century metropolis was a way of life: New York City founded its health department to address the yellow fever epidemic in 1793; cholera gripped the city for decades in the mid-1800s, and in the previous smallpox outbreak of 1894, as many as 150 smallpox cases per month were being reported.

Accordingly, as of 1893, controversial state legislation sanctioned the vaccination of schoolchildren and the exclusion of unvaccinated students from public schools.

After much debate, the court granted the city the right to exclude unvaccinated students from public schools, but ruled it unconstitutional to quarantine citizens who had not contracted smallpox and that “to vaccinate a person against his will, without legal authority to do so, would be an assault.”

Despite that vaccination reduced the smallpox mortality rate from a one-in-two chance to 1-in-75—and perhaps more importantly to New York City’s health officials at the time, that it could help limit the spreading of the disease—legislation around mandating it was more controversial in 1901-02 than it is today. Before scientist Louis T. Wright developed the intradermal smallpox vaccine (administered via a needle under the skin) in 1918, administering the vaccine involved cutting, scraping, and a wicked scar. It was little understood by the general public. Plus, it had been reported to lead to serious illness in itself. As more Americans encountered vaccines at the start of the 20th century, anti-vaccination leagues and societies sprung up across the country.

How could New York City’s health authorities convince people to undergo this procedure when it was so widely feared and little understood, and how could they make such a thing compulsory—even for only the highest risk populations—without being demonized by an increasingly anti-vaccination public?

Their strategy centered on low income—often immigrant—neighborhoods, and it came with a rash of misinformation.

*********

On January 2, 1901, the Washington, D.C. Evening Times reported that two young women escaped from doctors intending to take them away to North Brother Island. Florence Lederer, 27, and her friend Nelie Riley, 24, “showed unquestionable signs of smallpox,” sanitation superintendent Dillingham said, but were spry enough to escape from their apartment on Carmine Street in Greenwich Village and flee authorities, sleeping in a boarding house and hiding out “in the back rooms of saloons” until they were apprehended. They were coerced into providing a list of every place they visited while on the lam; subsequently, every saloon and boarding house in which they sought refuge was quarantined, every person on site vaccinated, and each space fumigated with formaldehyde according to protocol.

Five days later—now a month before the week of raids on the Upper East Side—the president of the New York Health Board, Michael Murphy, declared falsely there was “absolutely no truth” in charges that the health department had forcibly entered the homes of citizens nor vaccinated them against their wills.

The week after the raid, on February 6, New Orleans’ The Times Democrat would report on an interview with one Clifford Colgate Moore. New York was indeed in the throes of “an epidemic,” Moore, a doctor, declared, with 20,000 cases of smallpox and counting. “Authorities withheld the exact information on the subject,” he said, “because of the holiday shopping business. It was not deemed advisable to injure trade by announcing an epidemic of smallpox.” That the city had resorted to “compulsory vaccination” was noted in the headline.

“Rot! Rot! That’s all rot!,” Blauvelt maintained to the New York Times in a response on February 10. He refuted most everything Moore told the Times Democrat article, further stating he’d never heard of Moore (a Brooklyn native with degrees from the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute and the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University), nor had anyone working at the New York hospitals with which Moore was supposedly affiliated. He disputed that the city was forcing vaccinations on citizens, and most of all, he disputed Moore’s figures. “The number of cases in Manhattan has certainly been within 200 all told,” Blauvelt insisted, citing fewer than a dozen in Brooklyn total since late the previous year.

Moore’s figure of 20,000 was certainly inflated. Over the two years of the smallpox outbreak, reported cases reached more than 3,500 and reported deaths totaling 719.

But on the other hand, Blauvelt’s figures were undoubtedly low. First, people—patients, parents and doctors alike—were scared to report cases. Blauvelt himself may also have intentionally underreported, in the interest of averting panic. His health department successor, Royal S. Copeland, would do the same during the influenza outbreak in 1918, declining to close schools in an effort to “keep down the danger of panic,” and allow people, Copeland would tell the New York Times, “to go about their business without constant fear and hysterical sense of calamity.”

At the start of 1901, the small numbers that had been reported were “not quite enough to strike terror into a city of three-and-a-half million people,” writes Brandeis University history professor Michael Willrich, author of Pox: An American History, “but more than enough to cause the circulation of library books to plummet, the city’s regional trade to shrink, affluent families on the Upper West Side to cast out their servants, and the health department to hire seventy-five extra vaccinators.”

As the 1901 winter turned to spring, New Yorkers from all tiers of society heard about or witnessed their neighbors’ children being torn from their arms, or read in the papers that the conditions in the smallpox wards on North Brother Island were “worse than the black hole of Calcutta,” that “bed clothing [was] swarming with vermin,” and that there were no nurses and no medicine (though this was also disputed in follow-up reporting).

The more the epidemic was discussed, and the more reporting that happened on the separation of families and the terror of North Brother, the more citizens resolved to nurse afflicted children and family members back to health in secret at home. Women were seen carrying mysterious bundles out of their apartment buildings, which health inspectors speculated were smallpox-stricken babies being smuggled away to relative safety. And, throughout 1901, the more the number of smallpox cases in New York continued to grow.

Blauvelt and his colleagues continued their fight quietly: The tenants of homeless shelters were vaccinated, factory workers were vaccinated, and by May, even New York’s own policemen—in a surprise deployment of doctors to every precinct in the five boroughs—were compulsorily vaccinated, and one Irish patrolman’s eight-year-old son was taken to North Brother despite his and his wife’s tearful protestations and a daylong stand-off with authorities. (The heartbreaking spectacle drew a crowd, and 50 doctors were deployed to vaccinate the bystanders as soon as it was over.)

In 1902, the city health department unexpectedly declined to support a bill that would impose fines and even jail time on citizens who refused vaccines, fearing it would only fuel the opposition. Instead, their vaccination staff grew by another 150 men, raids continued, and, according to Willrich, their covert focus on vulnerable populations allowed them to administer 810,000 vaccinations in 1902 alone

Eventually, the outbreak was contained. Cases dropped by 25 percent from 1901 to 1902, and by early 1903, the surge had almost completely ebbed. In 1905, a long-awaited Supreme Court decision arrived. In the verdict of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the city found support for its raids and island quarantines when the courts affirmed “the right of the majority to override individual liberties when the health of the community requires it.”

The next contagious illness to strike New York wouldn’t strike until more than a decade later: polio. The victory won in Jacobson v. Massachusetts would be no help this time. With no vaccine at hand, city officials had to rely on quarantine alone and expanded the hospital on North Brother Island.

In the summer of 1916, polio claimed more than 2,000 victims, many of whom perished at the newly expanded island facilities. Ninety percent of them were children younger than ten.