How Saddam and ISIS Killed Iraqi Science

Within decades the country’s scientific infrastructure went from world-class to shambles. What happened?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/0a/b10ad7a0-05f6-42c4-878f-8f031606d51e/hhf0g2.jpg)

BAGHDAD – Even on a sunny midweek afternoon, the Tuwaitha nuclear complex is almost spookily silent.

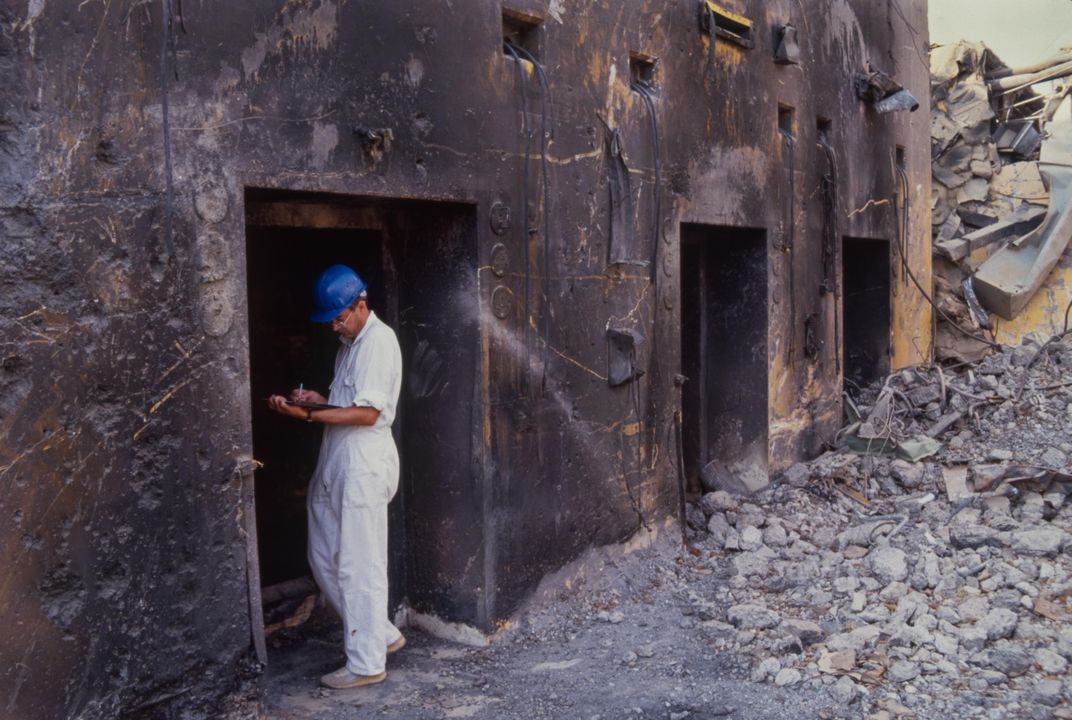

Bored soldiers, some half-asleep on their rifles, lounge behind sandbagged machine gun nests, while packs of mangy dogs hungrily pick their way through empty trash cans. Inside, among scores of crumbling laboratories, a few dozen disposal experts are painstakingly decommissioning the radioactive remains of Iraq’s notorious nuclear program. There’s so little traffic that the surrounding scrubland is beginning to reclaim some of the parking lots.

Not so long ago, this enormous base cut a radically different appearance. As the nerve center for Baghdad’s expansive science set-up since the 1960s, Tuwaitha once teemed with thousands of specialists who kept the facility running day and night. Underground bunkers sometimes convulsed with loud bangs from mysterious experiments, and senior officials shuttled in and out, puffed-up entourages in tow, as recounted in the 2001 book Saddam’s Bombmaker by an Iraqi nuclear scientist who was forced to help build the country’s atomic weapons.

Were it not for the thick, several mile-long protective blast walls, ex-employees say they’d scarcely recognize their old stomping ground. “This was the most important place in Iraq, but just look at it now,” said Omar Oraibi, a retired lab technician who also worked at the complex in the ’80s and ’90s, and now owns and operates a nearby roadside restaurant. “It just shows how far we’ve fallen.”

By “we,” he means Iraq’s trained scientists, and in many ways, he’s right.

For much of the 20th century, from the beginning of British rule through independence, World War II, the Cold War and up through the early years of Saddam Hussein’s ascent, Iraq was the Arab World’s foremost scientific power. Its infrastructure – nuclear reactors and all – rivaled that of many much richer countries. Tellingly, top Western universities still boast an inordinate number of Iraqi-born academics. Amid decades of war and other woes, it was scientific innovations in agriculture, healthcare and mineral extraction that more or less kept the country fed, functional and on its feet.

“Without conflicts, the whole of Iraq could have been developed, like Europe,” insists Ibrahim Bakri Razzaq, Director General of the Agricultural Research Institute at Iraq's Ministry of Science and Technology and five-decade veteran of the science program. Instead, Iraq today is considered a developing country by the United Nations and is still reeling from decades of conflict, including the U.S.-led invasion that toppled Saddam’s government in 2003, and the recent campaign against ISIS.

But in a cruel twist, the same prowess in science that contributed to Iraq’s rise also partly orchestrated its fall.

Having impressed Saddam, who became president in 1979, with their seemingly infinite skills, Iraqi government scientists were relentlessly exploited as vehicles for the dictator’s maniacal ambitions. Much of their talent, previously devoted to developing everything from climate-resilient seeds to cheap medical kits, was redirected to military purposes. As the regime then furiously hounded the country’s best and brightest to build nuclear weapons— the pursuit of which ostensibly led to the 2003 invasion—science inadvertently and indirectly underwrote Iraq’s ruin.

“We were made to do things that hurt not only us but the whole country,” said Mohammed, a former nuclear physicist who was part of the country’s arsenal building program for over a decade. (Mohammed asked to withhold his surname for security reasons.)

Today, the scientists who remain in Iraq battle decades of vilification from both inside and outside their country. That vilification has spawned a widespread distrust of the discipline itself, so much so that neighboring Arab Gulf states seldom issue visas to Iraqi scientists to attend regional conferences or workshops. “You cannot blame the scientists for what the politicians did,” says Moayyed Gassid, a longtime senior scientific researcher at the Atomic Energy Commission. But many do: As far as some contemporary Iraqis are concerned, it was science that largely enmeshed Iraq in its current mess. That’s partly why so many top scientists have left the country, and those who’ve remained work in much-reduced and sometimes dangerous circumstances.

If they are to throw off the reputation history has saddled them with, Iraq’s scientists will need international support and recognition of their plight. “We need the international science community to look at us as friends, not as part of the old regime,” said Fuad al-Musawi, the deputy minister of science and technology, who was imprisoned for several months under Saddam, allegedly due to this refusal to join the governing Baath political party. “Even during the past, we were working for our country, not for the regime.”

The Promise of Science

It was in the early years of Iraq’s monarchy in the 1920s that Baghdad first signaled its scientific promise. Recognizing the need to transform their poor and recently independent state, officials dispatched large numbers of bright young students to the United Kingdom for higher education. (Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire during World War I, Iraq was directly ruled from London for about 15 years and then heavily influenced from there for an additional two decades).

Many studied law, engineering and medicine—essential fields in a fledgling nation. But a portion soon gravitated towards the most cutting-edge of sciences. “Iraq has a deep pride in what it has done throughout history, and this seed was cultivated by the scholarship program,” said Hussain al-Shahristani, one of Iraq’s most prominent nuclear physicists. Throughout the 20th century and amid frequent regime changes, the most promising Iraqi students packed off to Western and Soviet universities, but returned to keep Iraqi science well-stocked with able personnel.

In the 1950s, under the auspices of the Baghdad Pact, a Cold War anti-communist alliance, Iraq began benefitting from considerable American scientific knowhow. The country was chosen to host a radioactivity training center, a facility to instruct locals in how to deal with the fallout from a nuclear strike. The capital was endowed with a sizeable library as part of President Eisenhower’s ‘Atoms for Peace,’ a program to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology.

In 1958, the U.S was even gearing up to provide Iraq with its first nuclear reactor, when suddenly the Western-friendly King Faisal II was toppled by the military. The country swiftly changed ideological tack. “Iraq went from the far right to the far left,” says Jafar Dia Jafar, the scientist who is widely seen as the father of Iraq’s nuclear enrichment program, when we met in his skyscraper office in Dubai.

Ultimately, the U.S. bequeathed that reactor to Iran, and in its stead Baghdad purchased one from its new Soviet ally. Fatefully for Washington, that facility kick-started a nuclear program that haunts it to this day.

The new Iraqi reactor went live in 1967 with Moscow-trained operating crews at the helm, prompting the creation of the Nuclear Research Center (NRC). Today, many Iraqi scientists—and Iraqis in general—consider the ’60s and ’70s to be the golden era of science. With new irradiating capacities now at their disposal, many of these highly trained scientists started churning out everything from varieties of fruit that could withstand insects to wheat variations that could cope with worsening droughts. The nation-building boom only accelerated after the 1973 Arab-Israeli war and subsequent oil embargo, which massively increased global energy prices and turned Iraq’s enormous reserves into a veritable cash cow.

“The budget was good, the labs were top notch, and we were well-looked after,” remembers Moayyed Gassid, the retired nuclear chemist. “It was a dream for us to build our country.”

A Dark Turn

But already there were hints of what was to come. Saddam Hussein, then a young army officer and officially only vice-chairman, had more or less assumed power by the early 1970s. On his watch, the science establishment began to take on an increasingly expansive role. Scientists were directed to help ramp up food production, ostensibly to help farmers but also to better insulate Iraq from external pressure as it pursued a more aggressive foreign policy. “During that time, Saddam and his followers were very nationalistic and didn’t want us to import any food from outside,” said Ibrahim Bakri Razzaq, the senior agricultural science official. By discarding unproductive seed types, importing extra farm labor from elsewhere in the Middle East, and building a host of new equipment-producing factories, he and his colleagues largely succeeded in making Iraq agriculturally self-sufficient.

In a forewarning of future purges, the NRC, too, became subject to political witch hunts. Officials jettisoned anyone, including Shahristani, who was deemed ideologically undesirable. “It wasn’t run along scientific lines. Some Baathists would come in and say, for example, ‘this guy is a communist,’ and would transfer him out,” says Jafar, who’d been personally summoned home by Saddam in 1975 after several years at CERN, the European nuclear research center in Switzerland. Having completed his doctorate in the U.K. at the age of 23, he had first worked at British nuclear facilities, before quickly working his way up the Iraqi chain of scientific command.

Most devastatingly of all, Saddam had by now seemingly set his sights on territorial gains—and he felt that science could come in handy, says Shahristani. Sure enough, when the dictator invaded neighboring Iran in 1980, only to quickly get bogged down, he turned to his scientists to break the impasse. “He decided to redirect the Nuclear Research Institute from peaceful applications to what he called strategic application, and even shifted the Scientific Research Institute, which had nothing to do with the military, to work on biological and chemical weapons,” says Shahristani, who headed the powerful ministry of oil for several years after Saddam’s toppling. “They needed these weapons to rework the map of the Middle East.”

Unwilling to participate in what he believed would be a fateful series of mistakes, the physicist was tortured and then jailed for ten years. Jafar was also placed under house arrest for 18 months when he tried to intercede on his colleague’s behalf. But worse was still to come.

Weaponization

Reports vary about when exactly Saddam resolved to build a bomb. Some suggest that was his intent from the offset. What can be said, though, is that the 1981 Israeli raid on the Osirak reactor at Tuwaitha crystallized his ambitions.

The regime insisted the facility, a recent purchase from France, was purely peaceful, but Israel feared it would one day be used to produce weapons-grade plutonium. This move, coming so soon after Iran had also targeted Tuwaitha, seems to have set the nuke-producing wheels in motion. “After the raid I was taken to see Saddam Hussein, who said: ‘I want you to go back and lead a program to eventually build a [nuclear] weapon, but it must be Iraqi, it must be completely indigenous,’” Jafar says. “It was clear by that point that the French were not going to rebuild the reactor, so it was going to be up to us.”

Over the next decade or so, Saddam and his acolytes pulled out all the stops to achieve that goal. They siphoned engineers, physicists and technicians from other branches of government and academia, and placed them at the program’s disposal, Jafar says. They established a new purpose-built division under the guise of Chemical Project 3 to achieve enrichment, and excavated large subterranean bunkers to conceal their work. “I’d decided we couldn’t produce a reactor to make plutonium because they have a big footprint. You can’t hide it; it would be detectable,” Jafar says. “So we decided to go for enrichment technology which was easier to hide.” Amid fierce popular anger within Iraq at the Israeli strike, the NRI was suddenly overwhelmed with applicants after years of sometimes struggling to attract recruits due to its onerous security restraints.

Still, despite these resources—and a direct hotline to the presidency through the Atomic Energy Commission’s influential heads—progress was slow. Iraq had to manufacture many of the necessary components itself. The country was working in extreme secrecy and under the limitations of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which bans the import of weapon-producing parts. Skilled engineers and welders cannibalized what they could elsewhere, but in many instances their only option was to build new factories, which could in turn produce what they needed. As the war with Iran raged on, only ending after eight years of extreme bloodshed in 1988, even Iraq’s oil-bloated coffers were feeling the strain.

“We did as much as we could, and with more time we would have been successful,” said Mohammed, the longtime nuclear scientist. “But the circumstances were challenging,”

Implosion

Over the course of just a few months in 1990, the weapons program—along with much of Iraq’s civilian science infrastructure—went up in smoke. After invading another of its neighbors, Kuwait, Iraq was pummeled for days by a U.S.-led international coalition until Saddam withdrew his forces. Eighteen science facilities were flattened during the Gulf air campaign, according to deputy minister Musawi, including the Tuwaitha nuclear reactor, which nearly melted down when it was struck without its protective shield. The power network was almost entirely knocked out. With an enormous stable of in-house technicians (which other ministries didn’t even know existed) the secret nuclear crews were hastily redeployed to restore electricity.

Fearing long-term chaos, many scientific elites also began to flee the country, only to be replaced by significantly less experienced professionals. “There was a brain-drain, people feared getting cut off,” Shahristani said.

In the meantime, the United States imposed debilitating economic sanctions to force Iraq to ditch its nuclear weapons program once and for all. Some science budgets were subsequently slashed by 90 percent; scholarships to international universities slowed to a trickle. Among the top-drawer scientists who remained, a large number were charged with producing domestic alternatives to goods Iraq was no longer able to import, or smuggle them over the border from Syria. “It was our job to develop things that we couldn’t get or afford to buy,” said Ibrahim Bakri Razzaq. After cobbling together a new fertilizer from agricultural waste, Bakri Razzaq was summoned to appear on television with Saddam himself, a keen gardener. “He insisted it made his flowers bloom even better than the foreign product,” the scientist recalls.

Iraq had outwardly declared and surrendered its full nuclear weapons capabilities by the end of 1995, the year that Hussein Kamel, Saddam’s son-in-law and former nuclear chief, defected to Jordan and divulged a wealth of details about his work. “We had to own up. The inspectors were everywhere,” Jafar said. “A nuclear program is a complex thing, with a whole infrastructure, which we couldn’t hide in those circumstances.” As history attests, the Bush Administration apparently didn’t believe Baghdad’s insistence that the program had been curtailed, and on March 20, 2003, the first of tens of thousands of U.S troops rolled into Iraq. The repercussions continue to reverberate across the Middle East.

After Saddam

For Iraqi science, the years since Saddam’s toppling have mostly been characterized by violence, neglect, and dire financial straits. Crucial facilities, including Tuwaitha, were ransacked by looters in 2003. Soon, stolen science apparatus were cropping up everywhere from street-side kebab stands to farm greenhouses. “Even here, we found 50 percent of the doors were missing. We had to start from scratch,” says Fuad al-Musawi from the ministry of science and technology’s sprawling compound in Baghdad’s leafy Karrada district. In a sign of enduring troubles, the walls, grounds and gates still crawl with gun-toting soldiers.

Another wave of top scientists sought sanctuary abroad amid worsening sectarian violence from 2004 to 2006, further depriving the country of talent it could ill-afford to lose. After two assassination attempts, one of which peppered his legs with shrapnel, Bakri Razzaq briefly fled Iraq. Many others have left and never returned.

As if things weren’t dreadful enough, along came ISIS, which over the course of three years from 2014 gutted almost every science facility it came across in northern and western Iraq. The jihadists demolished a vital seed technology center at Tikrit, and burnt down most of Mosul University’s laboratories. They allegedly press-ganged a number of captured scientists into weapons production, and killed several others for refusing to cooperate. In a bitterly ironic twist, Izzat al-Douri, who once presided over the Atomic Energy Commission under Saddam, is among the group’s top surviving commanders.

Now, perhaps more than ever, scientists’ skills are desperately required to revive Iraq’s crumbling agriculture, waterways and energy network. But against the backdrop of huge reconstruction costs and the global oil price crash, ministry of science and technology officials have struggled to secure the funds for anything beyond their most basic running costs.

Understandably, some scientists now struggle to profess much optimism about the future of their field. “Everything is gone. It started with the war with Iran. That destroyed the country, like cancer, little by little until we got to the end of the war,” said Bakri Razzaq. “Then we had the sanctions and everything since then.”

Yet others see some cause for guarded hope. The popular perception of science as an important and forward-thinking field endures. If only the international community would take an interest in getting the country’s infrastructure and training programs back on their feet, Baghdad scientists say they might once more play an important national-building role.

“Iraq has contributed to human civilization, and may be able to do it again,” says Hussain al-Shahristani. “How soon? Who knows. The country has big challenges. But if international institutions can create more opportunities for young Iraqi scientists, then science can be a big help.”