How Samuel Mudd Went From Lincoln Conspirator to Medical Savior

Banished to an island prison in the Gulf of Mexico, the doctor who set Booth’s broken leg saved dozens of lives in a yellow fever outbreak

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/19/4e19cf6e-73a3-472c-9c35-c9937cda5db2/1st_fl_casements_by_kl.jpg)

Fort Jefferson looks like a postcard version of paradise: a burnished brick fortress built on a coral island, circled by turquoise ocean stretching to the horizon in every direction. Magnificent frigatebirds and pelicans are the only permanent residents of the fort, which forms the heart of Dry Tortugas National Park, 70 miles west of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico. But 150 years ago, this was America’s largest military prison—and home to one of its most infamous men.

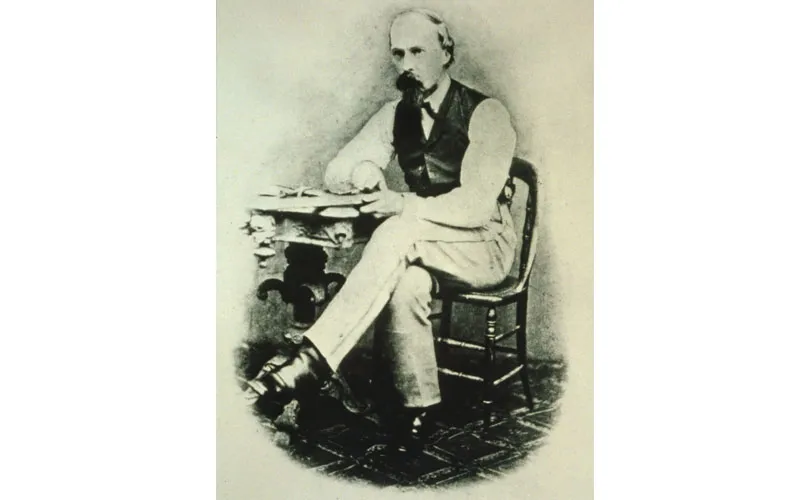

During the Civil War, Samuel A. Mudd was a surgeon and tobacco farmer in southern Maryland, a hotbed of Confederate sympathy. Thirty-one years old, with reddish hair, Mudd and his wife Sarah had four young children and a brand-new house when John Wilkes Booth, on the run after assassinating Abraham Lincoln, came to his farm needing medical help in the early morning hours of April 15, 1865. Though Mudd proclaimed his innocence in the assassination plot, testimony during his trial for conspiracy revealed that he had met Booth at least once prior to the murder, and setting Booth’s broken leg did him no favors. His fate sealed, Mudd received a life sentence in federal prison.

Three other Lincoln conspirators were convicted with Mudd. Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen, former Confederate soldiers from Baltimore, received life sentences for helping Booth concoct a plan—never carried out—to kidnap Lincoln. Edward (or Edman) Spangler, a carpenter, worked for John T. Ford at Ford’s Theatre and got six years for helping Booth escape. In July 1865, the four men were sent to Fort Jefferson in irons.

“We thought that we had at last found a haven of rest, although in a government Bastile [sic], where, shut out from the world, we would dwell and pass the remaining days of our life. It was a sad thought, yet it had to be borne,” Arnold wrote in his memoir.

Built in the 1840s, Fort Jefferson defended American waters from Caribbean pirates; during the war, the fort remained with the Union and blockaded Confederate ships trying to enter the Gulf of Mexico. Arched ports called casemates, arranged in three tiers around the fort’s six sides, had space for 420 heavy guns. Outside the massive walls, a seawater moat and drawbridge guarded the sally port, the fortress’ single entrance.

After the war, the Army transformed the fortress into a prison. Vacant casemates became open-air cells for more than 500 inmates serving time for desertion, mutiny, murder and other offenses. In July 1865, when the conspirators arrived, 30 officers and 531 enlisted men continued to augment the fort’s defenses, using prisoner labor to hoist cannons into position, build barracks and powder magazines, continue excavating the moat and repair masonry.

Mudd shared a cell with O’Laughlen, Arnold and Spangler. They had full view of the comings and goings of the fort’s inhabitants across the parade ground, the fort’s central field, as well as the arrival of the supply boats, which brought food, letters and newspapers. It was comfortable compared to the “dungeon,” a first-floor cell where Mudd was sent temporarily after he tried, and failed, to escape on a supply boat in September 1865. There, one small window overlooked the moat, where the fort’s toilets emptied.

Mudd suffered through a monotonous diet of bread, coffee, potatoes and onions; he refused to eat the imported meat, which spoiled quickly in the humid warmth. Bread consisted of “flour, bugs, sticks and dirt,” Arnold carped. Mudd complained about the squalid conditions in letters to his wife. “I am nearly worn out, the weather is almost suffocating, and millions of mosquitos, fleas, and bedbugs infest the whole island. We can’t rest day or night in peace for the mosquitos,” he wrote.

Fort Jefferson provided an unusually fertile breeding ground for the pests, including Aedes aegypti, the mosquito that carries the yellow fever virus. Because there was no natural source of drinking water—the “dry” in Dry Tortugas—the fort installed steam condensers to desalinate seawater. The fresh water was then stored in open barrels in the parade ground. “Those steam condensers are one of the main reasons yellow fever came about at the fort,” says Jeff Jannausch, lead interpreter for the Yankee Freedom III, the ferry that brings visitors to the Dry Tortugas today.

In the mid-19th century, though, no one knew what caused yellow fever or how it spread. The most popular theory held that bad air or “miasmas” brought on the high fever and delirium; bleeding from eyes, nose and ears; digested blood that came up as “black vomit,” and the jaundice that gave the fever its name.

The first case emerged on August 18, 1867, and there were three more by August 21. By this time, the number of prisoners at Fort Jefferson had dwindled to 52, but hundreds of officers and soldiers remained stationed at there. Cases spread. Thirty men in Company M got sick in a single night. “Quite a panic exists among soldiers and officers,” Mudd worried.

Without knowing the precise cause of the fever, the fort’s commanding officer, Major Val Stone, focused on containing the outbreak among the inhabitants as best he could. For men already showing symptoms, Stone had the post physician, Joseph Sim Smith, set up a makeshift quarantine hospital on Sand Key, a tiny island two-and-a-half miles away. Two companies were shipped to other keys to keep them from the contagion, and two remained to guard the inmates. “Prisoners had to stand the brunt of the fever, their only safety being an overruling Providence,” Arnold wrote in a 1902 newspaper article.

That left 387 souls at the fort. Smith contracted the fever on September 5 and died three days later. Mudd volunteered to take over the main hospital at Fort Jefferson, but not without some bitterness toward the government that had imprisoned him. “Deprived of liberty, banished from home, family and friends, bound in chains,” Mudd wrote, “for having exercised a simple act of common humanity in setting the leg of a man for whose insane act I had no sympathy, but which was in line with my professional calling. It was but natural that resentment and fear should rankle in my heart.” But once committed, he threw himself into the patients’ care.

Mudd, like most doctors of the time, believed in purging and sweating to treat fevers. He administered calomel, a mercury-based drug that induced vomiting, and followed up with a dose of Dover’s Powder, which contained ipecac and opium to encourage sweating. He permitted patients to drink warm herbal teas, but no cold water.

He also closed down the Sand Key quarantine and treated those patients at the main hospital, believing—correctly—that isolating them would ensure their deaths and do nothing to stop the fever’s spread. “Mudd demanded clean bedding and clothes for the sick. Before he took over, when someone died they’d throw the next patient into the same bed,” says Marilyn Jumalon, a docent at the Dr. Mudd House Museum in Maryland. “He implemented a lot of the hygienic steps that saved people’s lives.”

By October 1, nearly all of the fort’s inhabitants were ill, and an elderly doctor from Key West arrived to help Mudd with the cascade of cases. “The fever raged in our midst, creating havoc among those dwelling there. Dr. Mudd was never idle. He worked both day and night, and was always at post, faithful to his calling,” Arnold wrote.

Through his exertions, the number of deaths remained remarkably low. Of 270 cases, only 38 people, or 14 percent, died—including conspirator Michael O’Laughlen. In comparison, mortality rates from other outbreaks in the second half of the 19th century were much worse. In 1873, yellow fever hit Fort Jefferson again, and this time 14 of 37 infected men died—a mortality rate of nearly 37 percent. In an 1853 epidemic in New Orleans, 28 percent those afflicted died; in Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia in 1855, 43 percent; and in Memphis in 1878, 29 percent.

A grateful survivor, Lieutenant Edmund L. Zalinski, thought Mudd had earned clemency from the government. He petitioned President Andrew Johnson. “He inspired the hopeless with courage, and by his constant presence in the midst of danger and infection, regardless of his own life, tranquillized the fearful and desponding,” Zalinski wrote. “Many here who have experience his kind and judicious treatment can never repay him.” Two hundred-and-ninety-nine other officers and soldiers signed it.

Mudd sent a copy of the petition to his wife Sarah, who had visited Johnson several times to plead for her husband’s release, and she circulated it around Washington. In January 1869, a delegation of Maryland politicians met with Johnson at the White House and echoed Mrs. Mudd’s entreaty. They delivered a copy of the petition, and further argued that Mudd, Arnold and Spangler should be pardoned because they had nothing to do with planning Lincoln’s assassination.

The tide of public opinion was turning toward clemency, and Zalinski’s account gave Johnson leverage against critics. On February 8, 1869, less than a month before he would leave office and President-elect Grant would take over, President Johnson summoned Mrs. Mudd to the White House and gave her a copy of the pardon.

His life sentence dismissed, Mudd departed Fort Jefferson forever on March 11 of that year aboard the aptly named steamer Liberty. Spangler and Arnold were freed later that month.

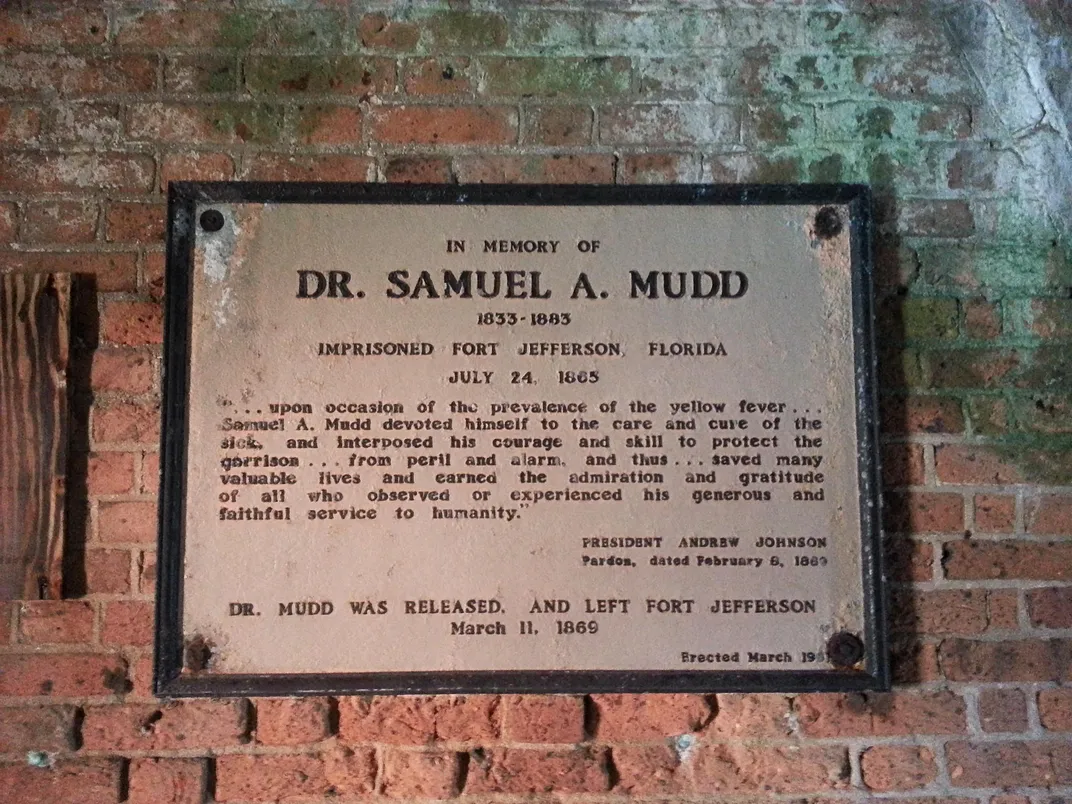

The doctor, just 35 but appearing much older, returned to his family in Maryland—but his presence is still vivid at Fort Jefferson. A plaque mounted in the dungeon where Mudd battled mosquitos echoes his official pardon. “Samuel A. Mudd devoted himself to the care and cure of the sick…and earned the admiration and gratitude of all who observed or experienced his generous and faithful service to humanity.”