On my first deployment to Iraq, in 2004, our infantry battalion of several hundred Marines lost 21 killed in action. Immediately, we erected our own modest memorials: An ever-expanding roster of the photographs of the fallen hung outside our battalion headquarters in Fallujah; many of us wrote the names of lost friends in black marker on the inside of our body armor, to keep them close; eventually, firebases were dedicated in their honor. The impulse to memorialize was powerful. We did it for them, but also for ourselves. A promise to remember was also a promise that if we, too, were killed, we would not be forgotten.

It has been 17 years since the attacks of September 11, and the wars we’ve been fighting since then haven’t yet ended. Already, though, in 2017, Congress passed the Global War on Terrorism War Memorial Act, which authorized the construction of a monument on the National Mall. In order to pass it, Congress had to exempt the memorial from a requirement that prohibits erecting such monuments until ten years after a war’s conclusion. Supporters argued that waiting wasn’t a reasonable option: Before too long, the war’s earliest combatants might not be around to witness the dedication, and besides, there’s no telling if and when these wars will finally conclude. Which, of course, only highlights the challenges—even the paradox—of memorializing an ongoing war that is now our nation’s longest overseas conflict.

Communities around the country have already erected their own memorials, approximately 130 across the 50 states as of this writing. Both privately and publicly funded, they are varied in size and design, placed in front of high schools, in public parks, at colleges and universities. With the future national monument in mind, this past Memorial Day weekend I set out to visit a few of them, to see whether they might shed some light on how to memorialize wars that haven’t ended, and might never.

* * *

I arrive on a muggy Friday afternoon at the Old North Church in Boston’s North End, made famous by Paul Revere, whose men hung lanterns—“One if by land, and two if by sea”—from its steepled bell tower. With a guide, I ascend into that same bell tower, which creaks in the wind and boasts commanding views of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill, as well as dozens of Bostonians sunbathing on their rooftops. As it happens my military career began in Boston, as a naval ROTC midshipman at Tufts University. This was right before the 9/11 attacks, and I had fully expected that I would serve in peacetime.

The outbreak of war is often unexpected. As if to reinforce this fact, my guide ushers me from the church’s highest point to its lowest: the crypt, where 1,100 sets of remains are walled into the church’s foundations. Many are British soldiers: The beginning of the Revolution took loyalists by surprise, and the basement of the Old North Church, where the congregation was largely loyal to the British crown, became one of the few places their British protectors could be peacefully interred. As the war dragged on, however, prominent revolutionaries would soon be mixed in among them, including Capt. Samuel Nicholson, the first commander of the USS Constitution, the oldest U.S. naval vessel still afloat, on whose decks I was commissioned a second lieutenant before heading to Iraq.

We exit the crypt and come into the light of the back garden, where since 2006 the church has housed a memorial to the fallen of the Iraq and Afghan wars, making it the oldest such memorial in the country. At first, the memorial was humble, a cross or Star of David made from popsicle sticks for each service member killed.

These markers proved less than durable, and the congregation soon changed the design to something more lasting. Now six tall posts are planted into the soil, in the shape of a horseshoe. Strung between each pair are wires, and hanging from them are dog tags, giving the effect of a shimmering, semicircular wall. On Saturday mornings, Bruce Brooksbank, a congregant and the memorial’s volunteer coordinator, visits for about two hours. He tends the garden, which is planted with red and white forget-me-nots. In his pocket he carries a few blank dog tags and, after checking iCasualties.org, he adds however many are required. At the time of writing, there are 6,978. When the dog tags catch the light, reflections dance on the ground. Bruce says that the light reminds him of angels, and the chime from the wind passing through them their voices.

A little girl steps into the garden and reaches for the dog tags. Her mother moves to stop her, but Bruce encourages her to touch them. “How do you like my garden?” he asks. Children are his favorite visitors, he explains. They arrive without political or historical preconceptions; they aren’t pro-war or antiwar; they didn’t vote for Bush or for Kerry. Their reaction is pure. Though they may not understand something as abstract as a pair of never-ending wars, they respond to the experience of seeing what’s been built here at the Old North Church.

The memorial is on a slight rise beside a brick pathway, and most of its visitors seem to happen upon it. When they learn what it is, they appear almost startled. In the hour that I sit with Bruce, nearly everyone who comes along slows to consider it. One young man, maybe a college student, strolls past wearing a tank top, khaki shorts, flip-flops and electric green plastic sunglasses. He stops and stares up at the memorial as though it’s a mountain he has yet to summit. Then he breaks down crying. He looks up at the monument a second time, and then breaks down again. The outburst is quick, less than a minute. Then he leaves.

When I ask Bruce if he has thoughts about a design for the national monument, he says, “Through simplicity you have power.”

* * *

Battleship Memorial Park sits on 175 acres at the northern tip of Mobile Bay, where the World War II-era USS Alabama rests at anchor. Scattered across the park’s acreage, as though staged for an invasion, is an impressive array of vintage military hardware. Calamity Jane, a retired B-52 Stratofortress, is installed next to where I’ve parked my rental car; it’s one of many long-range bombers that dropped its tonnage of explosives on North Vietnam. Its night camouflage is tattooed with red bomblets near the cockpit, each one designating a successful combat mission.

I’ve flown down to Mobile to see the Fallen Hero 9/11 Memorial, honoring Alabamians killed in service since 9/11, in whose shadow I’m now standing with Nathan Cox. Before joining the Marines, Nathan played fullback for the University of Alabama, where he also graduated summa cum laude. He’s got a bad knee from the football; sometimes it locks up on him. “While I was in the Corps, it got a lot worse,” he says, stretching out the leg.

Nathan, who like me was an infantry officer—in fact, we served in the same division within a year of each other in Iraq—led the initiative to erect this memorial, which was dedicated on September 11, 2015. “This memorial,” he says, “is just us trying to say something good.”

The centerpiece of the monument, designed by a local artist named Casey Downing Jr., also a veteran, is a stout, flat-topped black granite hexagonal base on top of which is a bronze replica of combat boots, a helmet and dog tags arrayed around a rifle bayoneted into the granite. Historically, to mark the location of fallen soldiers on the battlefield, their comrades would bayonet a rifle into the dirt. This has evolved into a traditional symbol honoring fallen soldiers. I remember the horseshoe of 21 boots, helmets, dog tags and rifles at our infantry battalion’s final memorial service.

Engraved on one side of the monument are the names of the Alabamians killed in these wars, with space, of course, for future additions. On each of the other five sides hangs a bronze bas-relief honoring a service member in his or her dress uniform from the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force and Coast Guard. Twin brick pathways, a shade darker than the brickwork surrounding the monument, lead from the back of the monument like shadows to a pair of rectangular black granite towers, representing the World Trade Center’s twin towers, standing side by side at about eight feet tall, and etched with a narrative describing the events of September 11 and the subsequent “Global War on Terror.” The text concludes with a quote attributed to George Orwell:

People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because

rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.

Nathan, who joined the Corps in response to the 9/11 attacks, and is now a successful real estate developer, spent eight years raising the half-million dollars needed to build the memorial from private donations. “Alabama’s such a patriotic place,” he says, holding his restless son, Luke, who squirms in his arms. “Everywhere you asked,” he adds, “people wanted to help.”

We stand together considering his memorial. “You know, when it was time for our generation’s war, I just wanted to be there,” he says. It is late in the afternoon, time for him to take his son home, and when he walks back to his truck, I notice that he limps a bit.

* * *

The next morning, a Sunday, I head north. The highway runs over the water and then across the marshlands that feed into Mobile Bay. I take on elevation, eventually entering Tennessee, where a half-hour outside of Nashville, in Murfreesboro, I stop to have dinner at a Cracker Barrel before settling into a motel room nearby.

Throughout the drive, I’ve been swapping text messages with Colby Reed, a former Marine corporal and Afghan war veteran who’s from the area. Colby has volunteered to take me to the local war memorial in Murfreesboro. We make plans to have breakfast the following morning. I ask him to recommend a place, and he suggests the Cracker Barrel, so I’m back there the next morning. It’s Monday—Memorial Day.

The place is packed, but Colby stands out as he makes his way through the crowd toward my table. He’s still in good shape, with broad shoulders, and he wears an olive drab T-shirt from his old unit, Third Battalion, Eighth Marine Regiment. He’s brought his wife with him. She’s in law school. He was a cop until recently and is now teaching criminal justice in high school while enrolled in college himself.

Colby enlisted in the Marines at 17, in 2009. When I ask him why, he says, “9/11.” When I point out to Colby that this seems like a rather dramatic reaction for a 9-year-old to have had, he says, “There’s a stigma around millennials, but people forget that millennials fought America’s longest wars as volunteers.”

I was born in 1980, which is supposed to make me a millennial, but I’ve never felt like one. I mentioned this once to a friend of mine about my age, a former bomb technician who also fought in Iraq. He said he’d never felt like a millennial either, so he’d come up with a different generational criterion: If you were old enough to have an adult reaction to the September 11 attacks, you’re not a millennial.

So maybe I’m not a millennial after all, and maybe Colby isn’t one either. At 9 years old he decided to enlist, and eight years later he went through with it, convincing his parents to sign an age waiver. Wars, which were once shared as generational touchstones, are no longer experienced the same way in this country because of our all-volunteer military. I’ve often wondered: In the past, did this make the return home less jarring? Maybe so. I’d rather be part of a lost generation, I think, than be the lost part of a generation.

After breakfast, we go to the Rutherford County Courthouse, in the Murfreesboro square, quintessential small-town America. Colby jokes how much the courthouse and the square resemble the set of Back to the Future. On the southeast corner of the courthouse green is the memorial, dedicated in 1948 by the local chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Admittedly, it isn’t much: five conjoined granite slabs of varying heights with names and places chiseled into the stone. Because it’s Memorial Day, a few roses have been left at the base. Across the slabs is engraved: THESE OUR WAR DEAD IN HONORED GLORY REST.

What we see is plain and unadorned. Unlike the dog tags refashioned as wind chimes in the Memorial Garden in Boston, nothing about this memorial is conceptual. Unlike the Fallen Hero 9/11 Memorial in Mobile, it isn’t grand or triumphant. This memorial is quiet, straightforward, conveying only the essentials. What else is there to say?

Colby stares at the names of five Murfreesboro native sons killed in Iraq and Afghanistan—his wife went to high school with one of the guys—along with dozens of names from the First World War, Second World War, Korea and Vietnam. Colby is aware of the story that I’m writing, and that nobody knows what the memorial on the National Mall will be like, which is why without prompting he says, “If they just gave us a little piece of land. A wall with our names. That’d be enough.”

* * *

Often, since coming home, I’ve had strangers tell me they can’t imagine what I went through. These comments are always made with kindness, with deference and sympathy; but I have always found them disempowering. If somebody can’t imagine what I went through, it means I’ve had experiences that have changed me and yet have made part of me fundamentally unknowable, even inaccessible, and disconnected from the person I was before. If that’s the case, it means I never truly get to return home: I am forever cut off from the person I was before these wars.

Why do we build these memorials anyway? We do it to honor the dead, of course. We do it so veterans and their families will have a place to gather and remember. But there’s something else, a less obvious reason but one I would say is most important. If a memorial is effective, if it’s done well, anyone should be able to stand in front of it and, staring up, feel something of what I felt when my friend J.P. Blecksmith, 24, from Pasadena, was killed by a sniper in Fallujah on Veterans Day, 2004, or when Garrett Lawton, his wife and two young sons back home in North Carolina, was killed by an IED in Herat Province, Afghanistan. If civilians can feel that ache—even a fraction of it—they might start to imagine what it was like for us. And if they can imagine that, we come home.

* * *

A week after Memorial Day, I find myself on the phone with Michael “Rod” Rodriguez, who leads the nonprofit Global War on Terrorism Memorial Foundation, which is responsible for overseeing the fund-raising, design and construction of the national memorial, which is currently scheduled for completion in 2024. The foundation, Rod tells me, plans to have an open competition for the design, as was done with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. After a few minutes, Rod mentions that he served with Seventh Special Forces Group in Afghanistan. So did I. It turns out that we share many friends, and our interview is quickly derailed as we begin swapping war stories. I try to get us back on topic by asking him the purpose of the new memorial. “What we were just doing,” Rod replies. “Talking about old times, remembering. It saves lives.”

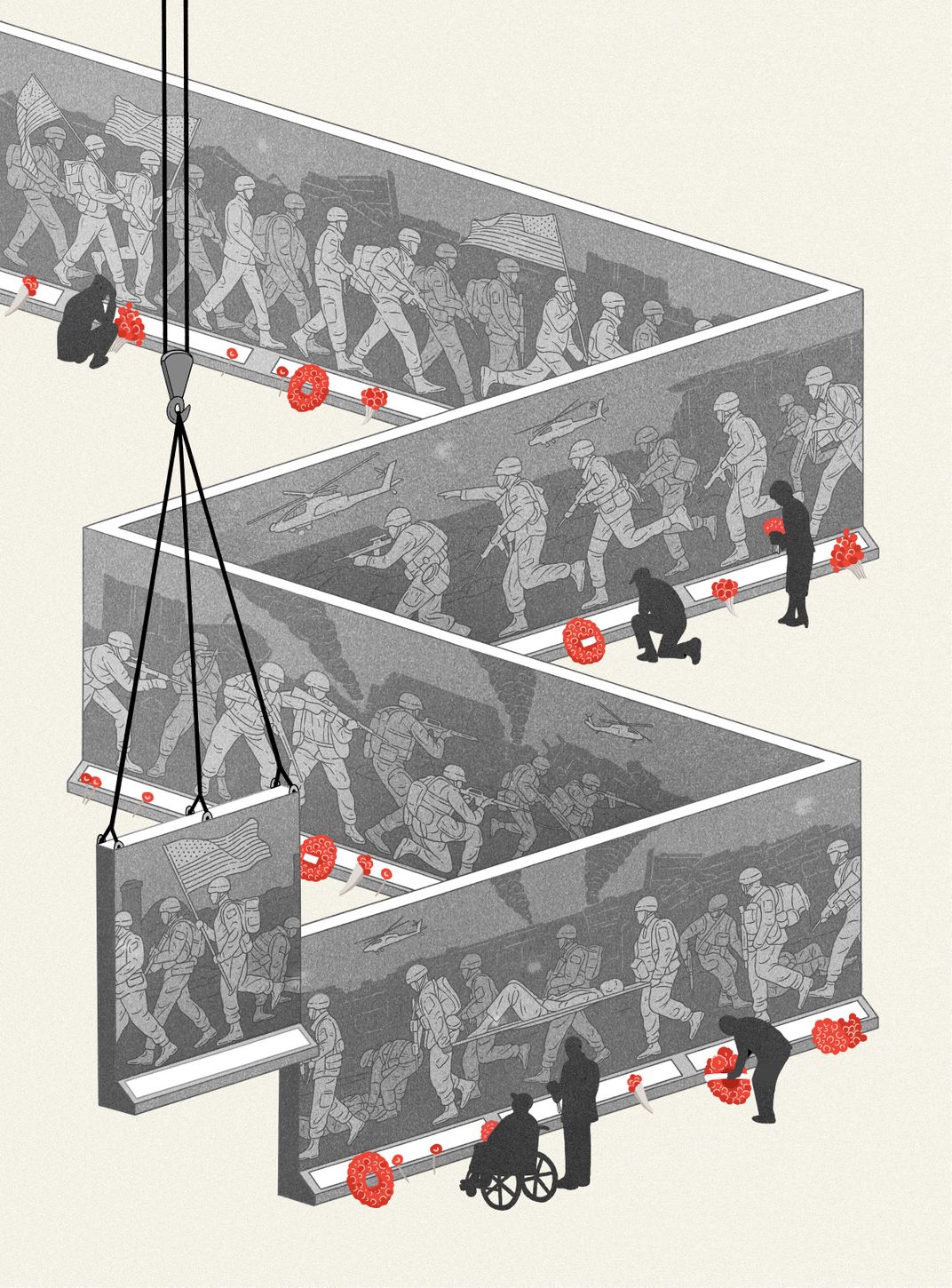

Rod emails me a map of the National Mall with about a half-dozen potential sites for the memorial, which will ultimately be decided by the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, whose mission is to protect the dignity of public space in the nation’s capital. Although real estate on the National Mall is precious, as of this writing four other war memorials are being planned for its grounds, commemorating the First World War, the Gulf War, Native American veterans and African-Americans who fought in the Revolution. And this doesn’t include a planned expansion of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which will add an underground visitors’ center, and the addition of a wall to the Korean War Veterans Memorial etched with the names of the 36,000 service members killed in that conflict.

The pace of construction on the Mall over the last three decades is remarkable, particularly considering that for the first 200 years of our nation’s history—which included nine major wars—not a single major war memorial existed on the Mall. What a society chooses to commemorate says a great deal about that society. Most of our national memorials are dedicated to our wars. Which raises a question: Is the National Mall turning into a kind of symbolic national graveyard?

Of course, one can certainly argue for the central role of these memorials in our capital, because none of our other accomplishments are possible without the freedom that our military has assured. But you need look no further than your own reflection in the shiny black granite of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial to understand that many of our wars are self-inflicted wounds.

That isn’t to say that we should commemorate only “morally good” wars, such as the Civil War or the Second World War. Those might be the conflicts we least need reminding of. It’s the more problematic wars in Vietnam, Korea, and, yes, Iraq and Afghanistan we need to memorialize in the most prominent spaces, lest future generations, while celebrating our successes, forget our mistakes.

* * *

Seth Moulton, a friend from the Marines, is now a congressman representing Massachusetts’ Sixth District. Along with Representative Mike Gallagher, from Wisconsin, Seth was an original sponsor of the bipartisan Global War on Terrorism War Memorial Act. I got in touch with Seth in Washington, D.C. and, with the memorial’s potential sites saved to my phone, we set out for a run on the Mall.

We meet in front of the Longworth House Office Building early on a Wednesday morning. It’s late July, muggy and hot. Seth wears an old desert-brown Under Armour shirt from his Iraq days. We jog west on the south side of the Mall, skirting the vast lawn along with the other joggers as we progress toward the Lincoln Memorial. Seth asks which of the memorials on my trip had resonated the most, and I confess that perhaps it was Murfreesboro: There was something honest about the places and names etched into stone. “A memorial like that isn’t really open to interpretation,” I say.

We huff past the World War II Memorial, with its swooping eagles clutching laurels in their talons and epic bas-reliefs conveying the drama of a vast struggle fought across continents. “In another life,” says Seth, “I would have liked to have been an architect.”

I ask him how he would design the Global War on Terrorism Memorial.

“It should be something that begins with idealistic goals, and then spins off into a quagmire,” he says. “It will need to be a memorial that can remain endless, as a tribute to an endless war.”

A memorial to an endless war is an interesting prospect. It’s been said that war is a phenomenon like other inevitable, destructive forces in nature—fires, hurricanes—although war is, of course, a part of human nature. Perhaps for the right artist, it will be an opportunity to make the truest war memorial possible, a monument to this fault in our nature.

If I had my way, I would get rid of all the war memorials and combine them into a single black wall of reflective granite, like Maya Lin’s design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. I’d place the wall around the Reflecting Pool, beneath the long shadows of the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial, the wall descending into the earth like something out of Dante. Etched into the wall would be names, and the very first would be Crispus Attucks, a black freeman shot dead by redcoats at the Boston Massacre, not far from the Old North Church. From there the wall would slope downward, each death taking it deeper into the earth, the angle of its descent defined by 1.3 million names, our nation’s cumulative war dead.

The wall itself would be endless. When a new war began, we wouldn’t erect a new monument. We wouldn’t have debates about real estate on the Mall. Instead we’d continue our descent. (If there’s one thing you learn in the military, it’s how to dig into the earth.) Deeper and deeper our wars would take us. To remember the fresh dead, we would have to walk past all the ones who came before. The human cost would be forever displayed in one monumental place, as opposed to scattered disconnectedly across the Mall.

The memorial would have a real-world function, too: Imagine if Congress passed legislation ensuring that every time a president signed a troop deployment order, he or she would have to descend into this pit. There, beside the very last name—the person most recently killed in defense of this country or its interests—there would be a special pen, nothing fancy, but this pen would be the only pen by law that could sign such an order.

That’s what I’m picturing as Seth and I arrive at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

“Run to the top?” I ask him.

“Not all the way,” he says, “just two-thirds,” explaining that he doesn’t think it’s right to jog on such hallowed ground. We wander inside the vestibule. Seth grows quiet. When I ask if he wants to continue our run, my voice echoes against the stone.

Soon we’re back outside, running down the stairs. “I love the Lincoln,” Seth says as we head east, toward the Capitol and past the memorials for Korea and for Vietnam. We talk about what our memorial will mean, the effect we hope it will have on our generation of veterans, and how we hope that one day we’ll be able to take our children to a memorial that conveys with sufficient emotion the experience not only of our war, but of war itself.

On our left we pass a duck pond. A layer of green sludge, maybe a centimeter thick, coats its surface. A dozen or so ducks, a squad’s worth, paddle through a quagmire of slime. One at a time they follow each other into the sludge and then determinedly try to keep together as they cross. A few seem stuck. We watch them as we run past. It’s a strangely grotesque sight in an otherwise pristine space.

Dark at the Crossing

A timely novel of stunning humanity and tension: a contemporary love story set on the Turkish border with Syria.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/47/2247d134-9d89-4596-844e-a0a2277370ee/janfeb2019_k05_warmemorials.jpg)