How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?

Fifty years after H.F. Verwoerd was assassinated in Parliament, the nation he once presided over reckons with its past

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/30/d130eaa7-ea9f-4583-8f1d-25ad13f57ad6/ap_352090602044.jpg)

On the afternoon of September 6, 1966, the architect of apartheid, H.F. Verwoerd, sat in the seat of the Prime Minister before the all-white Parliament of South Africa. With his white hair swept neatly to one side, he held himself with confidence. Verwoerd, 64, was the proud Afrikaner who set in stone the segregation of South Africa. He listened as bells called his fellow legislators to the chamber.

It was a day South Africans would remember for decades to come. At a quarter-past-two, a Parliamentary messenger suddenly rushed into the room. In his official uniform, he must have gone largely unnoticed. But then the messenger—later described as “a tall, powerful, gray-haired man in his late 40s”—produced a knife and stabbed Verwoerd four times in the chest and neck. The Prime Minister slumped forward, blood pouring from his body. By the time Verwoerd's colleagues had pinned down the assassin—a mentally ill half-Greek, half-black man named Dimitri Tsafendas—the carpet was stained with blood. Verwoerd was dead before he reached a hospital.

His funeral ceremony was attended by a quarter-million South Africans, the vast majority of whom were white. The architect was dead, but his policies were not; the system that Verwoerd helped to establish would continue to subjugate black South Africans for almost three decades.

In the 50 years that have passed since H.F. Verwoerd was assassinated, his reputation as a hero of white South Africa has eroded so thoroughly that he now symbolizes—even epitomizes—racism and brutality. His assassin, meanwhile, remains an enigma—a man whom some condemn, some celebrate and some simply ignore. Declared mentally unfit for trial, in part because he spoke bizarrely about a tapeworm that supposedly directed his actions, Tsafendas would end up outliving apartheid, but he would die behind bars as South Africa's longest-serving prisoner. To trace the legacy of both men today is to trace fault lines that still cut through South African society.

* * *

Among black South Africans, even the name Verwoerd inspires wrath. “I have vivid memories of what Verwoerd did to us,” says Nomavenda Mathiane, who worked for decades as an anti-apartheid journalist. She remembers that, during high school in 1960, her teacher announced that Verwoerd had been shot in an earlier, unsuccessful assassination attempt. The class broke out into applause.

Mathiane struggles to explain how powerful a symbol Verwoerd has become. At one point, by way of illustration, she compares him to Hitler. “We were happy that he died,” she remembers.

Verwoerd's notoriety began with one particular piece of legislation—the Bantu Education Act, passed in 1953. Like Jim Crow laws in the United States, the act preserved the privileges of white South Africans at the expense of people of color. It forced millions of black South Africans (who the apartheid government referred to as “Bantu”) to attend separate and decidedly unequal schools. “The Bantu must be guided to serve his own community in all respects,” Verwoerd said in June 1954. “There is no place for him in the European community above the level of certain forms of labour. Within his own community, however, all doors are open”

These memories deeply anger Mathiane. “After white people had taken the land, after white people had impoverished us in South Africa, the only way out of our poverty was through education,” she says. “And he came up with the idea of giving us an inferior education.”

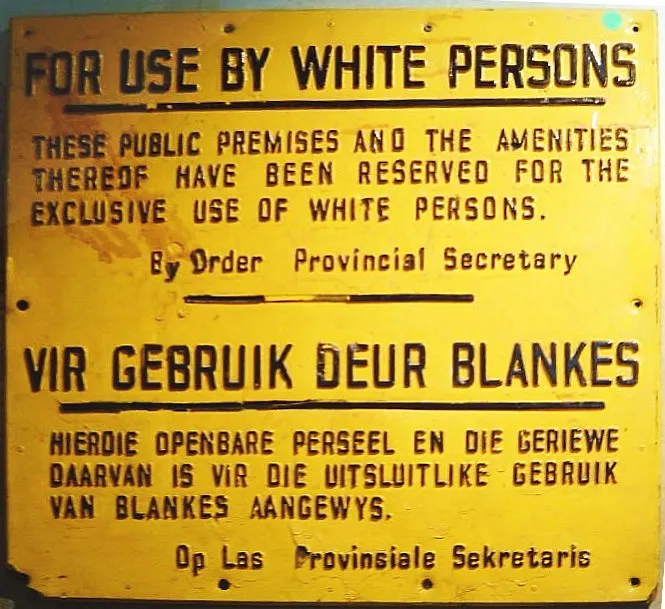

Verwoerd became prime minister in 1958, and during his tenure, segregation only worsened. Anti-apartheid activism was banned, and using earlier laws like the 1950 Group Areas Act and the 1953 Reservation of Separate Amenities Act, Verwoerd helped extend his education policies to the layout of cities and states. The philosophy of “grand apartheid” was used to justify the forced relocation of millions of non-white South Africans.

What South Africans disagree about is whether Verwoerd deserved his demise—and whether his assassin deserves our respect. Half a century after the assassination, in the Sunday Times newspaper, two recent articles suggest that there's still room for debate. “No place for heroes in story of Verwoerd and Tsafendas,” declared one headline. “Hendrik Verwoerd's killer a freedom fighter?” asked another.

“I think to some regard he should be taken as some sort of hero,” says Thobeka Nkabinde, a student at South Africa’s Stellenbosch University. “Hendrik Verwoerd was a bad person and a bad man, and his death can only by me be seen as a positive thing,” she adds. Harris Dousemetzis, a researcher based at Durham University, goes so far as to portray Tsafendas as a self-aware political assassin who may not have acted alone.

One reason the story still carries weight is that the psychological traces of Verwoerd are made physical in places like Cape Town, a city that remains notoriously segregated. “In South Africa, you drive into a town, and you see a predominantly white area, a predominantly black area, and then a predominantly colored area,” Nkabinde says, using the South African term for mixed-race. “The white area is the richest.”

Last year, Nkabinde joined the burgeoning “decolonization” movement that has been sweeping the country. Much like the efforts of activists and legislators in the United States to bring down or contextualize monuments to the Confederacy, South African activists seek to deny colonialist figures the honor of plaques, statues and place names. For her—a first-generation university student—this history was deeply personal. Nkabinde and her fellow students demanded the removal of a Verwoerd plaque; in response to their efforts, it was taken down, as was a statue of the mining magnate Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town.

* * *

For a long time, white South Africans viewed Verwoerd from a strikingly different perspective than blacks. A few still bear his name—including Melanie Verwoed, a well-known politician who adopted the family name by marriage (her ex-husband is H.F. Verwoerd's grandson). “If you speak to Afrikaans[-speaking] white people, as a rule, they would be very, very impressed that you're a Verwoerd.” Her own family viewed him as a smart and effective leader—a perspective that it took her many years to reject.

“When you carry a surname like Verwoerd in South Africa, you always get a reaction,” she says. When Melanie Verwoerd enters the country from abroad, border control officers raise their eyebrows. It can help when she explains that she fought late apartheid, and belonged to the same political party as Nelson Mandela. But her surname carries too much weight to be easily shrugged off. “Sometimes if I say I'm one of the good Verwoerds, jokingly, I get told there is no such thing.”

Only a tiny minority of South Africans stubbornly maintain that H.F. Verwoerd was a good man. I called his grandson Wynand Boshoff, who used to live in the “white homeland” of Orania, a remote town populated by Afrikaner nationalists. If not for Verwoerd, “we would have today had a much less educated black population,” Boshoff claims, despite wide agreement to the contrary among South Africans and historians. “As a ruler of South Africa, he did not do any additional harm to what had been done already by this whole clash of civilizations in Africa,” Boshoff adds. When asked if he thought Verwoerd's vision of apartheid was a good idea at the time, he says yes.

White nationalists notwithstanding, Verwoerd's status as a symbol of evil isn't likely to change anytime soon. His name is now shorthand for injustice; in Parliament, comparisons to Verwoerd have become a dagger of accusation that politicians brandish at each other. This, says Melanie Verwoerd, is for the most part a good thing. “It's helpful sometimes that there is one person or policy or deed that can be blamed. It certainly unifies people.”

At the same time, systems of oppression can seldom be summed up by the wrongdoing of an individual, and the idea of an “evil mastermind” seems better suited to comic books than history books. Just as Nelson Mandela has become one focal point in stories of liberation, Verwoerd has become a focal point in stories of injustice—a darkness against which wrongs are measured. Too rarely are his collaborators and successors condemned with such passion.

* * *

In 1994, the year apartheid finally collapsed, the anti-apartheid party ANC, or African National Congress, held a meeting in the old South African Parliament—the same chamber where Dimitri Tsafendas stabbed H.F. Verwoerd. Melanie Verwoerd, who had recently won a seat in Parliament, was in attendance. So were heroes of the fight for liberation: Nelson and Winnie Mandela, Walter and Albertina Sisulu, Thabo Mbeki.

“Everybody stood up in these benches where all this terrible apartheid legislation had been written, and where the ANC was banned, and where Nelson Mandela was demonized,” Melanie Verwoerd recalled. Mandela, who was about to become President of South Africa, sang Nkosi sikelel' iAfrika—“God Bless Africa”—and many wept as they took their seats.

History was almost palpable that day. “Mandela was sitting in the bench where Verwoerd had been assassinated many years before,” Melanie Verwoerd recalled. “And in fact the carpet still had a stain on it, which they never replaced, where Verwoerd's blood had been spilled.”

When freedom came to South Africa, the present didn't replace the past—it only added new layers to what had come before. This is a country that refuses to forget. “So much blood was spilled in this country for us to get where Mandela ultimately sat on that chair,” says the journalist Nomavenda Mathiane. Of Verwoerd, she says: “You cannot sweep a person like that under the carpet. People must know about him, people must write about him. Because if we don't say these things, people will forget, and more Verwoerds will arise.”

“But I must say that in spite of all that, we pulled through,” Mathiane adds, as if pushing Verwoerd's memory into the shadows, where it belongs. “We survived.”

Editor’s Note, September 22, 2016: This piece originally included a quote by Verwoerd that has since been determined to be inaccurate. It has been replaced with a statement read by Verwoerd before Parliament in June, 1954.