How Sitting Bull’s Fight for Indigenous Land Rights Shaped the Creation of Yellowstone National Park

The 1872 act that established the nature preserve provoked Lakota assertions of sovereignty

:focal(960x367:961x368)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d2/12/d2125c70-666d-4baf-889e-6c4e2ffd993a/sitting_bull.jpg)

Signed into law exactly 150 years ago, the 1872 Yellowstone Act proposed a massive government acquisition of more than 1,760 square miles in Wyoming Territory (an area larger than the state of Rhode Island). Now Yellowstone National Park, the tract of land included the Yellowstone Basin’s astounding geysers and other geothermal features, as well as its canyons, valleys, waterfalls and lakes. Legislators introduced the bill after geologist Ferdinand Hayden returned from a congressionally funded expedition to this “land of wonders” in the fall of 1871, bringing back 45 boxes of specimens, along with photographs and illustrations of the basin’s unique features.

As members of the House of Representatives debated the act in late February 1872, they focused on the threat it might pose to white settlers’ land rights. Then, John Taffe, a Republican from Nebraska and the chairman of the Committee on Territories, announced that he had a question: “It is whether this measure does not interfere with the Sioux [Očéthi Šakówiŋ] reservation.”

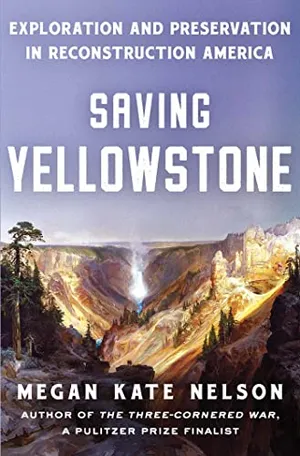

Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America

The propulsive and vividly told story of how Yellowstone became the world’s first national park amid the nationwide turmoil and racial violence of the Reconstruction era

Taffe’s query surprised his colleagues, most of whom did not consider Indigenous land rights an obstacle to federal projects in the West. The congressman, however, had the Očéthi Šakówiŋ at the forefront of his mind. Lakotas—one of the seven “council fires,” or nations, of the Očéthi Šakówiŋ—had been resisting white encroachment on their territory between the Upper Missouri River and Yellowstone since the early 1860s; the Húŋkpapȟa, a group of Lakotas under the leadership of Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Sitting Bull), were at the forefront of these efforts. Tensions had escalated in recent months as military forts and towns proliferated and railroad surveyors began entering Lakota territory. Taffe’s question acknowledged the growing power of Lakotas in the Northwest—and the extent to which they would continue to shape American exploration and preservation of Yellowstone.

Lakota peoples didn’t encounter large numbers of white migrants in their homelands until the summer of 1862, when thousands of gold miners began streaming toward the northern Rocky Mountains from boat landings on the Upper Missouri River. At the time, Lakota lands extended west from that river (which they called Mníšoše) to the Rockies and as far south as Colorado. Yellowstone Basin, located at the far western edge of their lands, was a shared Indigenous landscape used as a thoroughfare and hunting ground by many tribal nations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a4/e7/a4e74443-155f-4ae8-9e40-e63976dd7595/map-v5.jpg)

By 1862, Sitting Bull had become one of the Húŋkpapȟa Lakota’s most influential leaders. He walked with a slight limp—the legacy of wounds to his left foot and hip in battles with Flathead, Crow and United States soldiers. The slanted red eagle feather he wore in his hair commemorated these and other war wounds, while a vertical white one signified his many acts of bravery in battle.

The Húŋkpapȟa and their kin and allies surveilled the gold seekers and, when they had the advantage in numbers and terrain, attacked the settlers’ wagon trains. By the late 1860s, they had forced the U.S. Army from its forts along the Bozeman Trail. Sitting Bull and his fellow Lakota chiefs then sent a message to the federal officials who served as liaisons between the U.S. government and Native nations. “We wish you to stop the whites from traveling through our country,” they warned. “And if you do not stop them, we will.”

When Hayden set out on his scientific expedition to Yellowstone in the summer of 1871, Lakota assertions of sovereignty shaped his plans. Rather than take a boat up the Missouri, he traveled on the Union Pacific railroad to Ogden, Utah—the safest route for white travelers. In late July, as the Hayden expedition’s members were camped on the shores of Yellowstone Lake, a party of miners brought news that a Lakota raiding party had killed three men and stolen a herd of horses and cattle northwest of the basin. The attack prompted Hayden to accelerate his exploration of the great geyser basin along the Firehole River. He also lost half of his military escort, which was ordered to return to Fort Ellis outside Bozeman, Montana, to defend white citizens against another potential Lakota attack.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5b/a0/5ba05a68-970a-4f3f-8759-8916639aae0c/gettyimages-492840671.jpg)

Sitting Bull likely didn’t know much about Hayden’s expedition. He may not have even realized that his actions determined the scientist’s route and itinerary. Instead, Sitting Bull was more concerned with another set of survey teams out in the field that year: engineers working for the Northern Pacific Railroad, whose tracks would run from the Great Lakes to the Pacific coast, crossing Montana just north of Yellowstone, through the heart of Lakota country. Construction of the train track, chartered by Congress in 1864, had been delayed by weather and corporate disorganization. If the Northern Pacific were to be completed by 1876 (it was to be the “Centennial Line”), survey teams needed to map out a route through Yellowstone country as soon as possible, without facing resistance from the Lakota.

In the fall of 1871, during peace talks between the U.S. government and Lakotas in Montana Territory, Húŋkpapȟa leaders expressed their objections to all American incursions but particularly to the Northern Pacific survey teams. They knew that the railroad would bring more white settlers and, as a result, the buffalo herds they depended on for survival would disappear. “The Húŋkpapȟa would rather die fighting the Northern Pacific,” one Lakota argued, “than die of starvation because of it.”

That winter, newspaper coverage across the Northwest, as well as reports submitted to federal departments by Indian agents, territorial officials and explorers, were full of commentary about Sitting Bull’s power as a leader of his people. No wonder, then, that Taffe was concerned about the Yellowstone Act provoking the Lakota, along with their kin and allies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a6/e7/a6e7399e-e0c7-40e6-a112-56c4a3e55d1c/gettyimages-640485541.jpg)

Massachusetts Republican Henry Dawes dismissed Taffe’s concerns. The chairman of the Ways and Means Committee and one of the most powerful politicians in the House, Dawes had voted to fund Hayden’s expedition, and his son Chester had gone along as an assistant. “The Indians can no more live [in Yellowstone],” he told Taffe, “than they can upon the precipitous sides of the Yosemite valley.” To Dawes and almost all of his fellow legislators, potential Lakota land claims and the long-standing use of Yellowstone as a thoroughfare by Shoshone, Bannock, Crow, Flathead and Nez Perce peoples did not matter.

Dawes, who as a senator would later author the 1887 Severalty Act that took millions of acres of negotiated treaty lands from Indigenous nations to sell to white Americans, believed that the U.S. had always reserved the right to take Native lands for its own purposes. The federal government would exert this right in Yellowstone if necessary and by whatever means it chose. In the spring of 1871, Congress had inserted a rider in the Indian Appropriations Act that outlawed future treaty making with Indigenous peoples. From that point onward, the federal government refused to recognize Native sovereignty, instead escalating military campaigns that forced Native peoples onto reservations regardless of whether they signed peace agreements.

Even if the Lakotas objected to the passage of the Yellowstone Act, Dawes believed that they had no legal way to resist. The debate in the House ended there. The bill was brought to a vote, and the act was passed. When President Ulysses S. Grant signed it into law on March 1, 1872, the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act created the first national park in the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d9/7d/d97d2afc-eb9c-4f67-bb2b-a8ef789daf20/gettyimages-640506557.jpg)

For the first ten years of the park’s existence, no more than 1,030 people visited each year to see its natural wonders for themselves. This was due in part to continued Lakota assertions of sovereignty in the region. In August 1872, Sitting Bull’s warriors fought U.S. soldiers protecting two Northern Pacific survey teams, one of which was heading east from Bozeman and the other west from Mníšoše. In 1873, they encountered George Armstrong Custer for the first time, attacking the general’s Seventh Cavalry soldiers, who were protecting another group of railroad surveyors along the Yellowstone River. Construction of the Northern Pacific stalled, only to be completed in 1883.

Hayden, who led a second scientific expedition to Yellowstone in 1872, chose not to return in 1873, traveling to Colorado instead. “The Indians,” wrote Hayden, “are in a state of hostility over the greater portion of the country [in Montana] which remains to be explored.”

In 1875, as gold miners flooded the Black Hills in Dakota Territory and the U.S. government increasingly demanded that the Lakota surrender and move to reservations, Sitting Bull saw what the future held. “War is inevitable,” he declared. He would meet Custer, along with thousands of U.S. troops, along the Little Bighorn River the following year, scoring a decisive victory that had dire consequences. The U.S. Army, enraged at its loss, launched punitive campaigns against the Lakota and their allies, forcing Sitting Bull and his band into Canada. Five years later, the Lakota leader surrendered.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/66/88/6688c8f8-4c6d-42dd-a283-01574e296ab2/gettyimages-3091550.jpg)

The exploration and preservation of Yellowstone in 1871 and 1872 has long been recognized as a central moment in the history of American conservation. Less well known is its role in shaping Lakota history and U.S. Indian policy. This history—as well as 11,000 years of Indigenous use of Yellowstone—has largely been missing from the park’s signage or displays. Soon, however, that may change.

Last June, Yellowstone National Park officials issued a statement outlining their plans for 2022. “Our goal is to substantially engage every tribe connected to Yellowstone,” Superintendent Cam Sholly said. The anniversary, he added, is “a pivotal opportunity for us to listen to and work more closely with all associated tribes … to better honor their significantly important cultures and heritage in this area.”

These events will reveal a hard truth: that America’s “best idea” rested on remorseless campaigns of Native land dispossession. But they will also make known Indigenous resistance to these campaigns, and the survival and persistence of tribal nations who have long been stewards of lands across the Northwest. The events planned for 2022 will mark a new beginning, making a concerted effort to bring this history into the light.

Megan Kate Nelson is the author of Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America, from which this essay is adapted.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.