How the Sun Illuminates Spanish Missions On the Winter Solstice

Today, the rising sun shines on altars and other religious objects at many Spanish churches in the U.S. and Latin America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/6c/8a6cdbbd-88ac-47ae-be82-0c491d22bfff/image-20161214-2529-1uyk3ci.jpg)

On Dec. 21, nations in the Northern Hemisphere will mark the winter solstice – the shortest day and longest night of the year. For thousands of years people have marked this event with rituals and celebrations to signal the rebirth of the sun and its victory over darkness.

At hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of missions stretching from northern California to Peru, the winter solstice sun triggers an extraordinarily rare and fascinating event – something that I discovered by accident and first documented in one California church nearly 20 years ago.

At dawn on Dec. 21, a sunbeam enters each of these churches and bathes an important religious object, altar, crucifix or saint’s statue in brilliant light. On the darkest day of the year, these illuminations conveyed to native converts the rebirth of light, life and hope in the coming of the Messiah. Largely unknown for centuries, this recent discovery has sparked international interest in both religious and scientific circles. At missions that are documented illumination sites, congregants and Amerindian descendants now gather to honor the sun in the church on the holiest days of the Catholic liturgy with songs, chants and drumming.

I have since trekked vast stretches of the U.S. Southwest, Mexico and Central America to document astronomically and liturgically significant solar illuminations in mission churches. These events offer us insights into archaeology, cosmology and Spanish colonial history. As our own December holidays approach, they demonstrate the power of our instincts to guide us through the darkness toward the light.

Spreading the Catholic faith

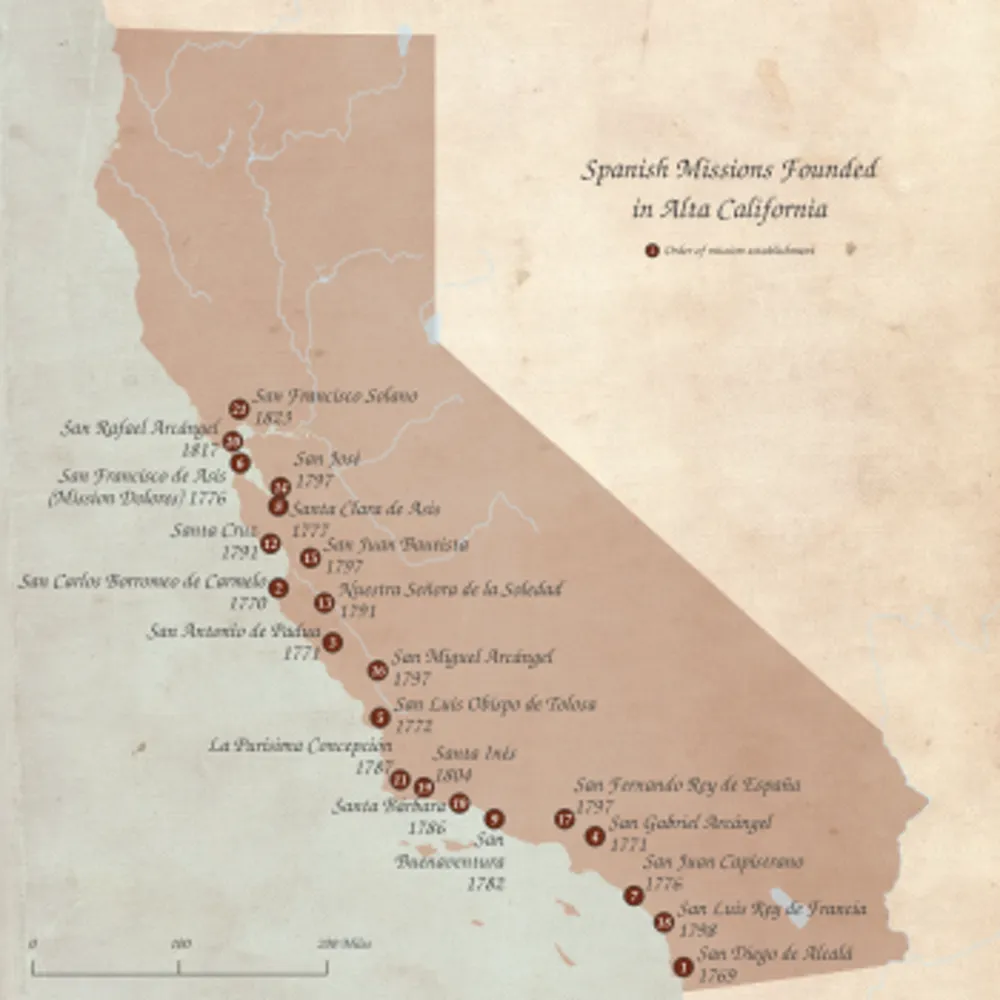

The 21 California missions were established between 1769 and 1823 by Spanish Franciscans, based in Mexico City, to convert Native Americans to Catholicism. Each mission was a self-sufficient settlement with multiple buildings, including living quarters, storerooms, kitchens, workshops and a church. Native converts provided the labor to build each mission complex, supervised by Spanish friars. The friars then conducted masses at the churches for indigenous communities, sometimes in their native languages.

Spanish friars like Fray Gerónimo Boscana also documented indigenous cosmologies and beliefs. Boscana’s account of his time as a friar describes California Indians’ belief in a supreme deity who was known to the peoples of Mission San Juan Capistrano as Chinigchinich or Quaoar.

As a culture hero, Indian converts identified Chinigchinich with Jesus during the Mission period. His appearance among Takic-speaking peoples coincides with the death of Wiyot, the primeval tyrant of the first peoples, whose murder introduced death into the world. And it was the creator of night who conjured the first tribes and languages, and in so doing, gave birth to the world of light and life.

Hunting and gathering peoples and farmers throughout the Americas recorded the transit of the solstice sun in both rock art and legend. California Indians counted the phases of the moon and the dawning of both the equinox and solstice suns in order to anticipate seasonally available wild plants and animals. For agricultural peoples, counting days between the solstice and equinox was all-important to scheduling the planting and harvesting of crops. In this way, the light of the sun was identified with plant growth, the creator and thereby the giver of life.

Discovering illuminations

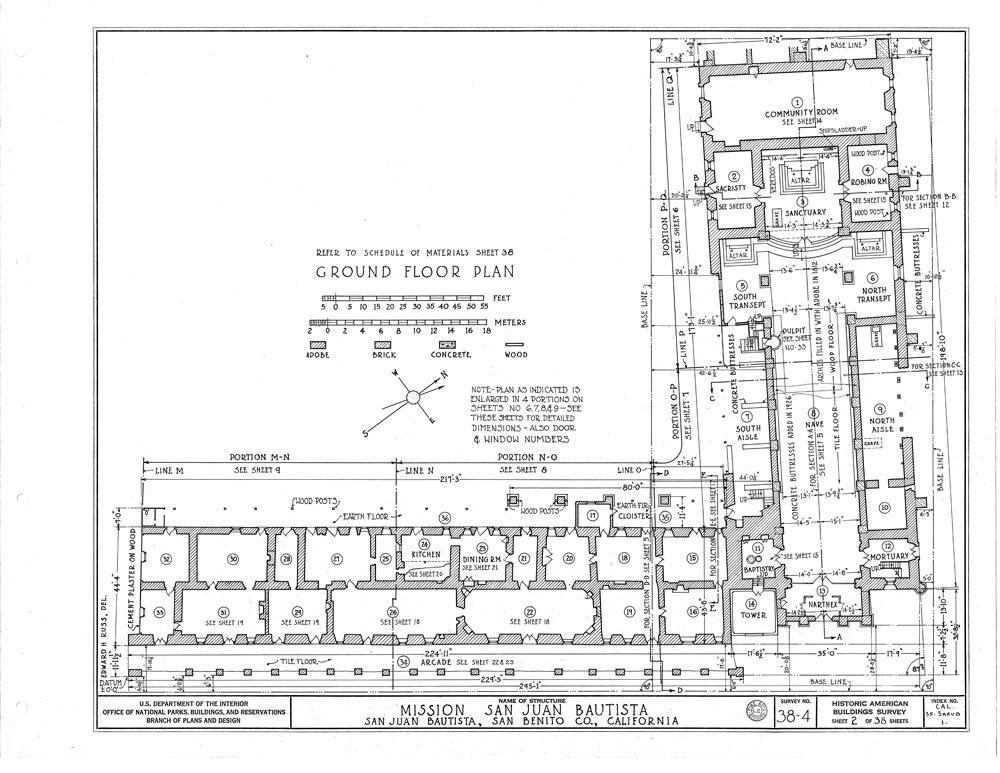

I first witnessed an illumination in the church at Mission San Juan Bautista, which straddles the great San Andreas Fault and was founded in 1797. The mission is also located a half-hour drive from the high-tech machinations of San Jose and the Silicon Valley. Fittingly, visiting the Old Mission on a fourth grade field trip many years earlier sparked my interest in archaeology and the history and heritage of my American Indian forebears.

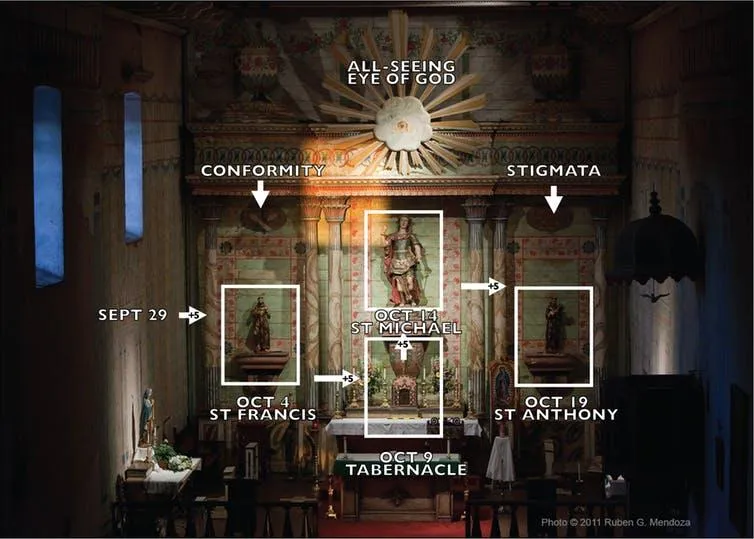

On Dec. 12, 1997, the parish priest at San Juan Bautista informed me that he had observed a spectacular solar illumination of a portion of the main altar in the mission church. A group of pilgrims observing the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe had asked to be admitted to the church early that morning. When the pastor entered the sanctuary, he saw an intense shaft of light traversing the length of the church and illuminating the east half of the altar. I was intrigued, but at the time I was studying the mission’s architectural history and assumed that this episode was unrelated to my work. After all, I thought, windows project light into the darkened sanctuaries of the church throughout the year.

One year later, I returned to San Juan Bautista on the same day, again early in the morning. An intensely brilliant shaft of light entered the church through a window at the center of the facade and reached to the altar, illuminating a banner depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe on her Feast Day in an unusual rectangle of light. As I stood in the shaft of light and looked back at the sun framed at the epicenter of the window, I couldn’t help but feel what many describe when, in the course of a near death experience, they see the light of the great beyond.

Only afterward did I connect this experience to the church’s unusual orientation, on a bearing of 122 degrees east of north – three degrees offset from the mission quadrangle’s otherwise square footprint. Documentation in subsequent years made it clear that the building’s positioning was not random. The Mutsun Indians of the mission had once revered and feared the dawning of the winter solstice sun. At this time, they and other groups held raucous ceremonies that were intended to make possible the resurrection of the dying winter sun.

Several years later, while I was working on an archaeological investigation at Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Carmel, I realized that the church at this site also was skewed off kilter from the square quadrangle around it – in this case, about 12 degrees. I eventually confirmed that the church was aligned to illuminate during the midsummer solstice, which occurs on June 21.

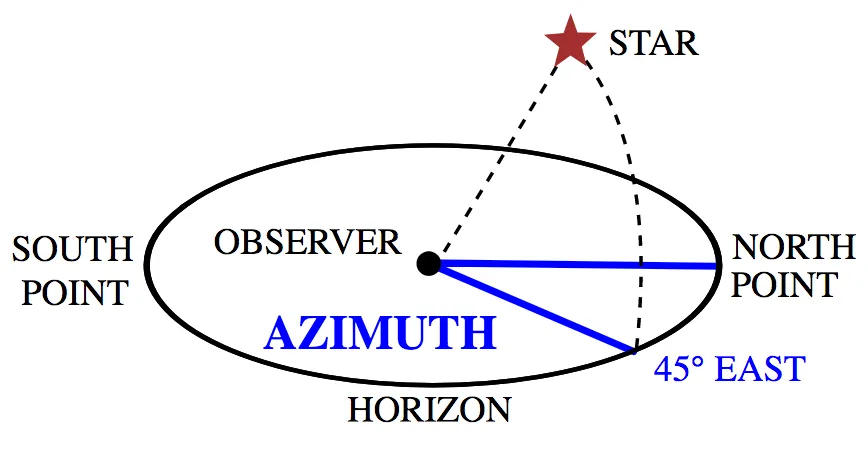

Next I initiated a statewide survey of the California mission sites. The first steps were to review the floor plans of the latest church structures on record, analyze historic maps and conduct field surveys of all 21 missions to identify trajectories of light at each site. Next we established the azimuth so as to determine whether each church building was oriented toward astronomically significant events, using sunrise and sunset data.

This process revealed that 14 of the 21 California missions were sited to produce illuminations on solstices or equinoxes. We also showed that the missions of San Miguel Arcángel and San José were oriented to illuminate on the Catholic Feast Days of Saint Francis of Assisi (Oct. 4) and Saint Joseph (March 19), respectively.

Soon thereafter, I found that 18 of the 22 mission churches of New Mexico were oriented to the all-important vernal or autumnal equinox, used by the Pueblo Indians to signal the agricultural season. My research now spans the American hemisphere, and recent findings by associates have extended the count of confirmed sites as far south as Lima, Peru. To date, I have identified some 60 illumination sites throughout the western United States, Mexico and South America.

Melding light with faith

It is striking to see how Franciscans were able to site and design structures that would produce illuminations, but an even more interesting question is why they did so. Amerindians, who previously worshiped the sun, identified Jesus with the sun. The friars reinforced this idea via teachings about the cristo helios, or “solar Christ” of early Roman Christianity.

Anthropologist Louise Burkhart’s studies affirm the presence of the “Solar Christ” in indigenous understandings of Franciscan teachings. This conflation of indigenous cosmologies with the teachings of the early Church readily enabled the Franciscans to convert followers across the Americas. Moreover, calibrations of the movable feast days of Easter and Holy Week were anchored to the Hebrew Passover, or the crescent new moon closest to the vernal equinox. Proper observance of Easter and Christ’s martyrdom therefore depended on the Hebrew count of days, which was identified with both the vernal equinox and the solstice calendar.

Orienting mission churches to produce illuminations on the holiest days of the Catholic calendar gave native converts the sense that Jesus was manifest in the divine light. When the sun was positioned to shine on the church altar, neophytes saw its rays illuminate the ornately gilded tabernacle container, where Catholics believe that bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Christ. In effect, they beheld the apparition of the Solar Christ.

The winter solstice, coinciding with both the ancient Roman festival of Sol Invictus (unconquered sun) and the Christian birth of Christ, heralded the shortest and darkest time of the year. For the California Indian, it presaged fears of the impending death of the sun. At no time was the sun in the church more powerful than on that day each year, when the birth of Christ signaled the birth of hope and the coming of new light into the world.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Rubén G. Mendoza, Chair/Professor, Division of Social, Behavioral & Global Studies, California State University, Monterey Bay