How the Battle of Little Bighorn Was Won

Accounts of the 1876 battle have focused on Custer’s ill-fated cavalry. But a new book offers a take from the Indian’s point of view

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Little-Bighorn-flats-631.jpg)

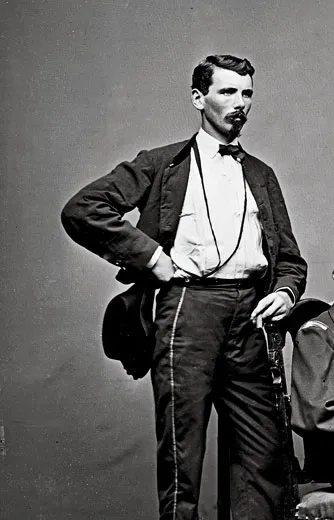

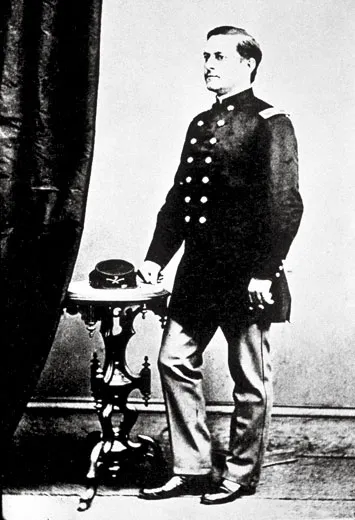

Editor’s note: In 1874, an Army expedition led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer found gold in the Black Hills, in present-day South Dakota. At the time, the United States recognized the hills as property of the Sioux Nation, under a treaty the two parties had signed six years before. The Grant administration tried to buy the hills, but the Sioux, considering them sacred ground, refused to sell; in 1876, federal troops were dispatched to force the Sioux onto reservations and pacify the Great Plains. That June, Custer attacked an encampment of Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho on the Little Bighorn River, in what is now Montana.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn is one of the most studied actions in U.S. military history, and the immense literature on the subject is devoted primarily to answering questions about Custer’s generalship during the fighting. But neither he nor the 209 men in his immediate command survived the day, and an Indian counterattack would pin down seven companies of their fellow 7th Cavalrymen on a hilltop over four miles away. (Of about 400 soldiers on the hilltop, 53 were killed and 60 were wounded before the Indians ended their siege the next day.) The experience of Custer and his men can be reconstructed only by inference.

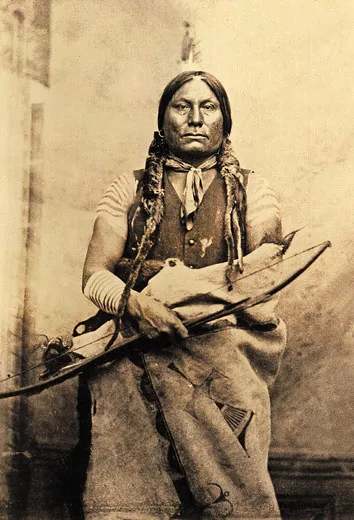

This is not true of the Indian version of the battle. Long-neglected accounts given by more than 50 Indian participants or witnesses provide a means of tracking the fight from the first warning to the killing of the last of Custer’s troopers—a period of about two hours and 15 minutes. In his new book, The Killing of Crazy Horse, veteran reporter Thomas Powers draws on these accounts to present a comprehensive narrative account of the battle as the Indians experienced it. Crazy Horse’s stunning victory over Custer, which both angered and frightened the Army, led to the killing of the chief a year later. “My purpose in telling the story as I did,” Powers says, “was to let the Indians describe what happened, and to identify the moment when Custer’s men disintegrated as a fighting unit and their defeat became inevitable.”

The sun was just cracking over the horizon that Sunday, June 25, 1876, as men and boys began taking the horses out to graze. First light was also the time for the women to poke up last night’s cooking fire. The Hunkpapa woman known as Good White Buffalo Woman said later she had often been in camps when war was in the air, but this day was not like that. “The Sioux that morning had no thought of fighting,” she said. “We expected no attack.”

Those who saw the assembled encampment said they had never seen one larger. It had come together in March or April, even before the plains started to green up, according to the Oglala warrior He Dog. Indians arriving from distant reservations on the Missouri River had reported that soldiers were coming out to fight, so the various camps made a point of keeping close together. There were at least six, perhaps seven, cheek by jowl, with the Cheyennes at the northern, or downriver, end near the broad ford where Medicine Tail Coulee and Muskrat Creek emptied into the Little Bighorn River. Among the Sioux, the Hunkpapas were at the southern end. Between them along the river’s bends and loops were the Sans Arc, Brulé, Minneconjou, Santee and Oglala. Some said the Oglala were the biggest group, the Hunkpapa next, with perhaps 700 lodges between them. The other circles might have totaled 500 to 600 lodges. That would suggest as many as 6,000 to 7,000 people in all, a third of them men or boys of fighting age. Confusing the question of numbers was the constant arrival and departure of people from the reservations. Those travelers—plus hunters from the camps, women out gathering roots and herbs and seekers of lost horses—were part of an informal early-warning system.

There were many late risers this morning because dances the previous night had ended only at first light. One very large tent near the center of the village—probably two lodges raised side by side—was filled with the elders, called chiefs by the whites but “short hairs,” “silent eaters” or “big bellies” by the Indians. As the morning turned hot and sultry, large numbers of adults and children went swimming in the river. The water would have been cold; Black Elk, the future Oglala holy man, then 12, would remember that the river was high with snowmelt from the mountains.

It was approaching midafternoon when a report arrived that U.S. troops had been spotted approaching the camp. “We could hardly believe that soldiers were so near,” the Oglala elder Runs the Enemy said later. It made no sense to him or the other men in the big lodge. For one thing, whites never attacked in the middle of the day. For several moments more, Runs the Enemy recalled, “We sat there smoking.”

Other reports followed. White Bull, a Minneconjou, was watching over horses near camp when scouts rode down from Ash Creek with news that soldiers had shot and killed an Indian boy at the fork of the creek two or three miles back. Women who had been digging turnips across the river some miles to the east “came riding in all out of breath and reported that soldiers were coming,” said the Oglala chief Thunder Bear. “The country, they said, looked as if filled with smoke, so much dust was there.” The soldiers had shot and killed one of the women. Fast Horn, an Oglala, came in to say he had been shot at by soldiers he saw near the high divide on the way over into the Rosebud valley.

But the first warning to bring warriors on the run probably occurred at the Hunkpapa camp around 3 o’clock, when some horse raiders—Arikara (or Ree) Indians working for the soldiers, as it turned out—were seen making a dash for animals grazing in a ravine not far from the camp. Within moments shooting could be heard at the south end of camp. Peace quickly gave way to pandemonium—shouts and cries of women and children, men calling for horses or guns, boys sent to find mothers or sisters, swimmers rushing from the river, men trying to organize resistance, looking to their weapons, painting themselves or tying up their horses’ tails.

As warriors rushed out to confront the horse thieves, people at the southernmost end of the Hunkpapa camp were shouting alarm at the sight of approaching soldiers, first glimpsed in a line on horseback a mile or two away. By 10 or 15 minutes past 3 o’clock, Indians had boiled out of the lodges to meet them. Now came the first shots heard back at the council lodge, convincing Runs the Enemy to put his pipe aside at last. “Bullets sounded like hail on tepees and tree tops,” said Little Soldier, a Hunkpapa warrior. The family of chief Gall—two wives and their three children—were shot to death near their lodge at the edge of the camp.

But now the Indians were rushing out and shooting back, making show enough to check the attack. The whites dismounted. Every fourth man took the reins of three other horses and led them along with his own into the trees near the river. The other soldiers deployed in a skirmish line of perhaps 100 men. It was all happening very quickly.

As the Indians came out to meet the skirmish line, straight ahead, the river was to their left, obscured by thick timber and undergrowth. To the right was open prairie rising away to the west, and beyond the end of the line, a force of mounted Indians rapidly accumulated. These warriors were swinging wide, swooping around the end of the line. Some of the Indians, He Dog and Brave Heart among them, rode out still farther, circling a small hill behind the soldiers.

By then the soldiers had begun to bend back around to face the Indians behind them. In effect the line had halted; firing was heavy and rapid, but the Indians racing their ponies were hard to hit. Ever-growing numbers of men were rushing out to meet the soldiers while women and children fled. No more than 15 or 20 minutes into the fight the Indians were gaining control of the field; the soldiers were pulling back into the trees that lined the river.

The pattern of the Battle of the Little Bighorn was already established—moments of intense fighting, rapid movement, close engagement with men falling dead or wounded, followed by sudden relative quiet as the two sides organized, took stock and prepared for the next clash. As the soldiers disappeared into the trees, Indians by ones and twos cautiously went in after them while others gathered nearby. Shooting fell away but never halted.

Two large movements were unfolding simultaneously—most of the women and children were moving north down the river, leaving the Hunkpapa camp behind, while a growing stream of men passed them on the way to the fighting—“where the excitement was going on,” said Eagle Elk, a friend of Red Feather, Crazy Horse’s brother-in-law. Crazy Horse himself, already renowned among the Oglala for his battle prowess, was approaching the scene of the fighting at about the same time.

Crazy Horse had been swimming in the river with his friend Yellow Nose when they heard shots. Moments later, horseless, he met Red Feather bridling his pony. “Take any horse,” said Red Feather as he prepared to dash off, but Crazy Horse waited for his own mount. Red Feather didn’t see him again until 10 or 15 minutes later, when the Indians had gathered in force near the woods where the soldiers had taken refuge.

It was probably during those minutes that Crazy Horse had prepared himself for war. In the emergency of the moment many men grabbed their weapons and ran toward the shooting, but not all. War was too dangerous to treat casually; a man wanted to be properly dressed and painted before charging the enemy. Without his medicine and time for a prayer or song, he would be weak. A 17-year-old Oglala named Standing Bear reported that after the first warnings Crazy Horse had called on a wicasa wakan (medicine man) to invoke the spirits and then took so much time over his preparations “that many of his warriors became impatient.”

Ten young men who had sworn to follow Crazy Horse “anywhere in battle” were standing nearby. He dusted himself and his companions with a fistful of dry earth gathered up from a hill left by a mole or gopher, a young Oglala named Spider would recall. Into his hair Crazy Horse wove some long stems of grass, according to Spider. Then he opened the medicine bag he carried about his neck, took from it a pinch of stuff “and burned it as a sacrifice upon a fire of buffalo chips which another warrior had prepared.” The wisp of smoke, he believed, carried his prayer to the heavens. (Others reported that Crazy Horse painted his face with hail spots and dusted his horse with the dry earth.) Now, according to Spider and Standing Bear, he was ready to fight.

By the time Crazy Horse caught up with his cousin Kicking Bear and Red Feather, it was hard to see the soldiers in the woods, but there was a lot of shooting; bullets clattered through tree limbs and sent leaves fluttering to the ground. Several Indians had already been killed, and others were wounded. There was shouting and singing; some women who had stayed behind were calling out the high-pitched, ululating cry called the tremolo. Iron Hawk, a leading man of Crazy Horse’s band of Oglala, said his aunt was urging on the arriving warriors with a song:

Brothers-in-law, now your friends have come.

Take courage.

Would you see me taken captive?

At just this moment someone near the timber cried out, “Crazy Horse is coming!” From the Indians circling around behind the soldiers came the charge word—“Hokahey!” Many Indians near the woods said that Crazy Horse repeatedly raced his pony past the soldiers, drawing their fire—an act of daring sometimes called a brave run. Red Feather remembered that “some Indian shouted, ‘Give way; let the soldiers out. We can’t get at them in there.’ Soon the soldiers came out and tried to go to the river.” As they bolted out of the woods, Crazy Horse called to the men near him: “Here are some of the soldiers after us again. Do your best, and let us kill them all off today, that they may not trouble us anymore. All ready! Charge!”

Crazy Horse and all the rest now raced their horses directly into the soldiers. “Right among them we rode,” said Thunder Bear, “shooting them down as in a buffalo drive.” Horses were shot and soldiers tumbled to the ground; a few managed to pull up behind friends, but on foot most were quickly killed. “All mixed up,” said the Cheyenne Two Moons of the melee. “Sioux, then soldiers, then more Sioux, and all shooting.” Flying Hawk, an Oglala, said it was hard to know exactly what was happening: “The dust was thick and we could hardly see. We got right among the soldiers and killed a lot with our bows and arrows and tomahawks. Crazy Horse was ahead of all, and he killed a lot of them with his war club.”

Two Moons said he saw soldiers “drop into the river-bed like buffalo fleeing.” The Minneconjou warrior Red Horse said several troops drowned. Many of the Indians charged across the river after the soldiers and chased them as they raced up the bluffs toward a hill (now known as Reno Hill, for the major who led the soldiers). White Eagle, the son of Oglala chief Horned Horse, was killed in the chase. A soldier stopped just long enough to scalp him—one quick circle-cut with a sharp knife, then a yank on a fistful of hair to rip the skin loose.

The whites had the worst of it. More than 30 were killed before they reached the top of the hill and dismounted to make a stand. Among the bodies of men and horses left on the flat by the river below were two wounded Ree scouts. The Oglala Red Hawk said later that “the Indians [who found the scouts] said these Indians wanted to die—that was what they were scouting with the soldiers for; so they killed them and scalped them.”

The soldiers’ crossing of the river brought a second breathing spell in the fight. Some of the Indians chased them to the top of the hill, but many others, like Black Elk, lingered to pick up guns and ammunition, to pull the clothes off dead soldiers or to catch runaway horses. Crazy Horse promptly turned back with his men toward the center of the great camp. The only Indian to offer an explanation of his abrupt withdrawal was Gall, who speculated that Crazy Horse and Crow King, a leading man of the Hunkpapa, feared a second attack on the camp from some point north. Gall said they had seen soldiers heading that way along the bluffs on the opposite bank.

The fight along the river flat—from the first sighting of soldiers riding toward the Hunkpapa camp until the last of them crossed the river and made their way to the top of the hill—had lasted about an hour. During that time, a second group of soldiers had shown itself at least three times on the eastern heights above the river. The first sighting came only a minute or two after the first group began to ride toward the Hunkpapa camp—about five minutes past 3. Ten minutes later, just before the first group formed a skirmish line, the second group was sighted across the river again, this time on the very hill where the first group would take shelter after their mad retreat across the river. At about half-past 3, the second group was seen yet again on a high point above the river not quite halfway between Reno Hill and the Cheyenne village at the northern end of the big camp. By then the first group was retreating into the timber. It is likely that the second group of soldiers got their first clear view of the long sprawl of the Indian camp from this high bluff, later called Weir Point.

The Yanktonais White Thunder said he saw the second group make a move toward the river south of the ford by the Cheyenne camp, then turn back on reaching “a steep cut bank which they could not get down.” While the soldiers retraced their steps, White Thunder and some of his friends went east up and over the high ground to the other side, where they were soon joined by many other Indians. In effect, White Thunder said, the second group of soldiers had been surrounded even before they began to fight.

From the spot where the first group of soldiers retreated across the river to the next crossing place at the northern end of the big camp was about three miles—roughly a 20-minute ride. Between the two crossings steep bluffs blocked much of the river’s eastern bank, but just beyond the Cheyenne camp was an open stretch of several hundred yards, which later was called Minneconjou Ford. It was here, Indians say, that the second group of soldiers came closest to the river and to the Indian camp. By most Indian accounts it wasn’t very close.

Approaching the ford at an angle from the high ground to the southeast was a dry creek bed in a shallow ravine now known as Medicine Tail Coulee. The exact sequence of events is difficult to establish, but it seems likely that the first sighting of soldiers at the upper end of Medicine Tail Coulee occurred at about 4 o’clock, just as the first group of soldiers was making its dash up the bluffs toward Reno Hill and Crazy Horse and his followers were turning back. Two Moons was in the Cheyenne camp when he spotted soldiers coming over an intervening ridge and descending toward the river.

Gall and three other Indians were watching the same soldiers from a high point on the eastern side of the river. Well out in front were two soldiers. Ten years later, Gall identified them as Custer and his orderly, but more probably it was not. This man he called Custer was in no hurry, Gall said. Off to Gall’s right, on one of the bluffs upriver, some Indians came into sight as Custer approached. Feather Earring, a Minneconjou, said Indians were just then coming up from the south on that side of the river “in great numbers.” When Custer saw them, Gall said, “his pace became slower and his actions more cautious, and finally he paused altogether to await the coming up of his command. This was the nearest point any of Custer’s party ever got to the river.” At that point, Gall went on, Custer “began to suspect he was in a bad scrape. From that time on Custer acted on the defensive.”

Others, including Iron Hawk and Feather Earring, confirmed that Custer and his men got no closer to the river than that—several hundred yards back up the coulee. Most of the soldiers were still farther back up the hill. Some soldiers fired into the Indian camp, which was almost deserted. The few Indians at Minneconjou Ford fired back.

The earlier pattern repeated itself. Little stood in the soldiers’ way at first, but within moments more Indians began to arrive, and they kept coming—some crossing the river, others riding up from the south on the east side of the river. By the time 15 or 20 Indians had gathered near the ford, the soldiers had hesitated, then begun to ride up out of Medicine Tail Coulee, heading toward high ground, where they were joined by the rest of Custer’s command.

The battle known as the Custer Fight began when the small, leading detachment of soldiers approaching the river retreated toward higher ground at about 4:15. This was the last move the soldiers would take freely; from this moment on everything they did was in response to an Indian attack growing rapidly in intensity.

As described by Indian participants, the fighting followed the contour of the ground, and its pace was determined by the time it took for Indians to gather in force and the comparatively few minutes it took for each successive group of soldiers to be killed or driven back. The path of the battle follows a sweeping arc up out of Medicine Tail Coulee across another swale into a depression known as Deep Coulee, which in turn opens up and out into a rising slope cresting at Calhoun Ridge, rising to Calhoun Hill, and then proceeds, still rising, past a depression in the ground identified as the Keogh site to a second elevation known as Custer Hill. The high ground from Calhoun Hill to Custer Hill was what men on the plains called “a backbone.” From the point where the soldiers recoiled away from the river to the lower end of Calhoun Ridge is about three-quarters of a mile—a hard, 20-minute uphill slog for a man on foot. Shave Elk, an Oglala in Crazy Horse’s band, who ran the distance after his horse was shot at the outset of the fight, remembered “how tired he became before he got up there.” From the bottom of Calhoun Ridge to Calhoun Hill is another uphill climb of about a quarter-mile.

But it would be a mistake to assume that all of Custer’s command—210 men—advanced in line from one point to another, down one coulee, up the other coulee and so on. Only a small detachment had approached the river. By the time this group rejoined the rest, the soldiers occupied a line from Calhoun Hill along the backbone to Custer Hill, a distance of a little over half a mile.

The uphill route from Medicine Tail Coulee over to Deep Coulee and up the ridge toward Custer Hill would have been about a mile and a half or a little more. Red Horse would later say that Custer’s troops “made five different stands.” In each case, combat began and ended in about ten minutes. Think of it as a running fight, as the survivors of each separate clash made their way along the backbone toward Custer at the end; in effect the command collapsed back in on itself. As described by the Indians, this phase of the battle began with the scattering of shots near Minneconjou Ford, unfolding then in brief, devastating clashes at Calhoun Ridge, Calhoun Hill and the Keogh site, climaxing in the killing of Custer and his entourage on Custer Hill and ending with the pursuit and killing of about 30 soldiers who raced on foot from Custer Hill toward the river down a deep ravine.

Back at Reno Hill, just over four miles to the south, the soldiers preparing their defenses heard three episodes of heavy firing—one at 4:25 in the afternoon, about ten minutes after Custer’s soldiers turned back from their approach to Minneconjou Ford; a second about 30 minutes later; and a final burst about 15 minutes after that, dying off before 5:15. Distances were great, but the air was still, and the .45/55 caliber round of the cavalry carbine made a thunderous boom.

At 5:25 some of Reno’s officers, who had ridden out with their men toward the shooting, glimpsed from Weir Point a distant hillside swarming with mounted Indians who seemed to be shooting at things on the ground. These Indians were not fighting; more likely they were finishing off the wounded, or just following the Indian custom of putting an extra bullet or arrow into an enemy’s body in a gesture of triumph. Once the fighting began it never died away, the last scattering shots continuing until night fell.

The officers at Weir Point also saw a general movement of Indians—more Indians than any of them had ever encountered before—heading their way. Soon the forward elements of Reno’s command were exchanging fire with them, and the soldiers quickly returned to Reno Hill.

As Custer’s soldiers made their way from the river toward higher ground, the country on three sides was rapidly filling with Indians, in effect pushing as well as following the soldiers uphill. “We chased the soldiers up a long, gradual slope or hill in a direction away from the river and over the ridge where the battle began in good earnest,” said Shave Elk. By the time the soldiers made a stand on “the ridge”—evidently the backbone connecting Calhoun and Custer hills—the Indians had begun to fill the coulees to the south and east. “The officers tried their utmost to keep the soldiers together at this point,” said Red Hawk, “but the horses were unmanageable; they would rear up and fall backward with their riders; some would get away.” Crow King said, “When they saw that they were surrounded they dismounted.” This was cavalry tactics by the book. There was no other way to make a stand or maintain a stout defense. A brief period followed of deliberate fighting on foot.

As Indians arrived they got off their horses, sought cover and began to converge on the soldiers. Taking advantage of brush and every little swale or rise in the ground to hide, the Indians made their way uphill “on hands and knees,” said Red Feather. From one moment to the next, the Indians popped up to shoot before dropping back down again. No man on either side could show himself without drawing fire. In battle the Indians often wore their feathers down flat to help in concealment. The soldiers appear to have taken off their hats for the same reason; a number of Indians noted hatless soldiers, some dead and some still fighting.

From their position on Calhoun Hill the soldiers were making an orderly, concerted defense. When some Indians approached, a detachment of soldiers rose up and charged downhill on foot, driving the Indians back to the lower end of Calhoun Ridge. Now the soldiers established a regulation skirmish line, each man about five yards from the next, kneeling in order to take “deliberate aim,” according to Yellow Nose, a Cheyenne warrior. Some Indians noted a second skirmish line as well, stretching perhaps 100 yards away along the backbone toward Custer Hill. It was in the fighting around Calhoun Hill, many Indians reported later, that the Indians suffered the most fatalities—11 in all.

But almost as soon as the skirmish line was thrown out from Calhoun Hill, some Indians pressed in again, snaking up to shooting distance of the men on Calhoun Ridge; others made their way around to the eastern slope of the hill, where they opened a heavy, deadly fire on soldiers holding the horses. Without horses, Custer’s troops could neither charge nor flee. Loss of the horses also meant loss of the saddlebags with the reserve ammunition, about 50 rounds per man. “As soon as the soldiers on foot had marched over the ridge,” the Yanktonais Daniel White Thunder later told a white missionary, he and the Indians with him “stampeded the horses...by waving their blankets and making a terrible noise.”

“We killed all the men who were holding the horses,” Gall said. When a horse holder was shot, the frightened horses would lunge about. “They tried to hold on to their horses,” said Crow King, “but as we pressed closer, they let go their horses.” Many charged down the hill toward the river, adding to the confusion of battle. Some of the Indians quit fighting to chase them.

The fighting was intense, bloody, at times hand to hand. Men died by knife and club as well as by gunfire. The Cheyenne Brave Bear saw an officer riding a sorrel horse shoot two Indians with his revolver before he was killed himself. Brave Bear managed to seize the horse. At almost the same moment, Yellow Nose wrenched a cavalry guidon from a soldier who had been using it as a weapon. Eagle Elk, in the thick of the fighting at Calhoun Hill, saw many men killed or horribly wounded; an Indian was “shot through the jaw and was all bloody.”

Calhoun Hill was swarming with men, Indian and white. “At this place the soldiers stood in line and made a very good fight,” said Red Hawk. But the soldiers were completely exposed. Many of the men in the skirmish line died where they knelt; when their line collapsed back up the hill, the entire position was rapidly lost. It was at this moment that the Indians won the battle.

In the minutes before, the soldiers had held a single, roughly continuous line along the half-mile backbone from Calhoun Hill to Custer Hill. Men had been killed and wounded, but the force had remained largely intact. The Indians heavily outnumbered the whites, but nothing like a rout had begun. What changed everything, according to the Indians, was a sudden and unexpected charge up over the backbone by a large force of Indians on horseback. The central and controlling part Crazy Horse played in this assault was witnessed and later reported by many of his friends and relatives, including He Dog, Red Feather and Flying Hawk.

Recall that as Reno’s men were retreating across the river and up the bluffs on the far side, Crazy Horse had headed back toward the center of camp. He had time to reach the mouth of Muskrat Creek and Medicine Tail Coulee by 4:15, just as the small detachment of soldiers observed by Gall had turned back from the river toward higher ground. Flying Hawk said he had followed Crazy Horse down the river past the center of camp. “We came to a ravine,” Flying Hawk later recalled, “then we followed up the gulch to a place in the rear of the soldiers that were making the stand on the hill.” From his half-protected vantage at the head of the ravine, Flying Hawk said, Crazy Horse “shot them as fast as he could load his gun.”

This was one style of Sioux fighting. Another was the brave run. Typically the change from one to the other was preceded by no long discussion; a warrior simply perceived that the moment was right. He might shout: “I am going!” Or he might yell “Hokahey!” or give the war trill or clench an eagle bone whistle between his teeth and blow the piercing scree sound. Red Feather said Crazy Horse’s moment came when the two sides were keeping low and popping up to shoot at each other—a standoff moment.

“There was a great deal of noise and confusion,” said Waterman, an Arapaho warrior. “The air was heavy with powder smoke, and the Indians were all yelling.” Out of this chaos, said Red Feather, Crazy Horse “came up on horseback” blowing his eagle bone whistle and riding between the length of the two lines of fighters. “Crazy Horse...was the bravest man I ever saw,” said Waterman. “He rode closest to the soldiers, yelling to his warriors. All the soldiers were shooting at him but he was never hit.”

After firing their rifles at Crazy Horse, the soldiers had to reload. It was then that the Indians rose up and charged. Among the soldiers, panic ensued; those gathered around Calhoun Hill were suddenly cut off from those stretching along the backbone toward Custer Hill, leaving each bunch vulnerable to the Indians charging them on foot and horseback.

The soldiers’ way of fighting was to try to keep an enemy at bay, to kill him from a distance. The instinct of Sioux fighters was the opposite—to charge in and engage the enemy with a quirt, bow or naked hand. There is no terror in battle to equal physical contact—shouting, hot breath, the grip of a hand from a man close enough to smell. The charge of Crazy Horse brought the Indians in among the soldiers, whom they clubbed and stabbed to death.

Those soldiers still alive at the southern end of the backbone now made a run for it, grabbing horses if they could, running if they couldn’t. “All were going toward the high ground at end of ridge,” the Brulé Foolish Elk said.

The skirmish lines were gone. Men crowded in on each other for safety. Iron Hawk said the Indians followed close behind the fleeing soldiers. “By this time the Indians were taking the guns and cartridges of the dead soldiers and putting these to use,” said Red Hawk. The boom of the Springfield carbines was coming from Indian and white fighters alike. But the killing was mostly one-sided.

In the rush of the Calhoun Hill survivors to rejoin the rest of the command, the soldiers fell in no more pattern than scattered corn. In the depression in which the body of Capt. Myles Keogh was found lay the bodies of some 20 men crowded tight around him. But the Indians describe no real fight there, just a rush without letup along the backbone, killing all the way; the line of bodies continued along the backbone. “We circled all round them,” Two Moons said, “swirling like water round a stone.”

Another group of the dead, ten or more, was left on the slope rising up to Custer Hill. Between this group and the hill, a distance of about 200 yards, no bodies were found. The mounted soldiers had dashed ahead, leaving the men on foot to fend for themselves. Perhaps the ten who died on the slope were all that remained of the foot soldiers; perhaps no bodies were found on that stretch of ground because organized firing from Custer Hill held the Indians at bay while soldiers ran up the slope. Whatever the cause, Indian accounts mostly agree that there was a pause in the fighting—a moment of positioning, closing in, creeping up.

The pause was brief; it offered no time for the soldiers to count survivors. By now, half of Custer’s men were dead, Indians were pressing in from all sides, the horses were wounded, dead or had run off. There was nowhere to hide. “When the horses got to the top of the ridge the gray ones and bays became mingled, and the soldiers with them were all in confusion,” said Foolish Elk. Then he added what no white soldier lived to tell: “The Indians were so numerous that the soldiers could not go any further, and they knew that they had to die.”

The Indians surrounding the soldiers on Custer Hill were now joined by others from every section of the field, from downriver where they had been chasing horses, from along the ridge where they had stripped the dead of guns and ammunition, from upriver, where Reno’s men could hear the beginning of the last heavy volley a few minutes past 5. “There were great numbers of us,” said Eagle Bear, an Oglala, “some on horseback, others on foot. Back and forth in front of Custer we passed, firing all of the time.”

Kill Eagle, a Blackfeet Sioux, said the firing came in waves. His interviewer noted that he clapped “the palms of his hands together very fast for several minutes” to demonstrate the intensity of the firing at its height, then clapped slower, then faster, then slower, then stopped.

In the fight’s final stage, the soldiers killed or wounded very few Indians. As Brave Bear later recalled: “I think Custer saw he was caught in [a] bad place and would like to have gotten out of it if he could, but he was hemmed in all around and could do nothing only to die then.”

Exactly when custer died is unknown; his body was found in a pile of soldiers near the top of Custer Hill surrounded by others within a circle of dead horses. It is probable he fell during the Indians’ second, brief and final charge. Before it began, Low Dog, an Oglala, had called to his followers: “This is a good day to die: follow me.” The Indians raced up together, a solid mass, close enough to whip each other’s horses with their quirts so no man would linger. “Then every chief rushed his horse on the white soldiers, and all our warriors did the same,” said Crow King.

In their terror some soldiers threw down their guns, put their hands in the air and begged to be taken prisoner. But the Sioux took only women as prisoners. Red Horse said they “did not take a single soldier, but killed all of them.”

The last 40 or more of the soldiers on foot, with only a few on horseback, dashed downhill toward the river. One of the mounted men wore buckskins; Indians said he fought with a big knife. “His men were all covered with white dust,” said Two Moons.

These soldiers were met by Indians coming up from the river, including Black Elk. He noted that the soldiers were moving oddly. “They were making their arms go as though they were running, but they were only walking.” They were likely wounded—hobbling, lurching, throwing themselves forward in the hope of escape.

The Indians hunted them all down. The Oglala Brings Plenty and Iron Hawk killed two soldiers running up a creek bed and figured they were the last white men to die. Others said the last man dashed away on a fast horse upriver toward Reno Hill, and then inexplicably shot himself in the head with his own revolver. Still another last man, it was reported, was killed by the sons of the noted Santee warrior chief Red Top. Two Moons said no, the last man alive had braids on his shirt (i.e., a sergeant) and rode one of the remaining horses in the final rush for the river. He eluded his pursuers by rounding a hill and making his way back upriver. But just as Two Moons thought this man might escape, a Sioux shot and killed him. Of course none of these “last men” was the last to die. That distinction went to an unknown soldier lying wounded on the field.

Soon the hill was swarming with Indians—warriors putting a final bullet into enemies, and women and boys who had climbed the long slopes from the village. They joined the warriors who had dismounted to empty the pockets of the dead soldiers and strip them of their clothes. It was a scene of horror. Many of the bodies were mutilated, but in later years Indians did not like to talk about that. Some said they had seen it but did not know who had done it.

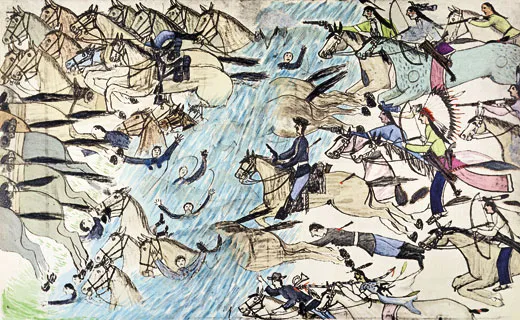

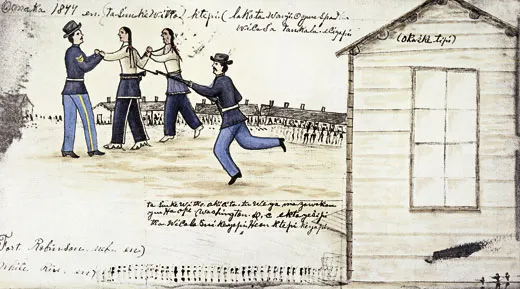

But soldiers going over the field in the days following the battle recorded detailed descriptions of the mutilations, and drawings made by Red Horse leave no room for doubt that they took place. Red Horse provided one of the earliest Indian accounts of the battle and, a few years later, made an extraordinary series of more than 40 large drawings of the fighting and of the dead on the field. Many pages were devoted to fallen Indians, each lying in his distinctive dress and headgear. Additional pages showed the dead soldiers, some naked, some half-stripped. Each page depicting the white dead showed severed arms, hands, legs, heads. These mutilations reflected the Indians’ belief that an individual was condemned to have the body he brought with him to the afterlife.

Acts of revenge were integral to the Indians’ notion of justice, and they had long memories. The Cheyenne White Necklace, then in her middle 50s and wife of Wolf Chief, had carried in her heart bitter memories of the death of a niece killed in a massacre whites committed at Sand Creek in 1864. “When they found her there, her head was cut off,” she said later. Coming up the hill just after the fighting had ended, White Necklace came upon the naked body of a dead soldier. She had a hand ax in her belt. “I jumped off my horse and did the same to him,” she recalled.

Most Indians claimed that no one really knew who the leader of the soldiers was until long after the battle. Others said no, there was talk of Custer the very first day. The Oglala Little Killer, 24 years old at the time, remembered that warriors sang Custer’s name during the dancing in the big camp that night. Nobody knew which body was Custer’s, Little Killer said, but they knew he was there. Sixty years later, in 1937, he remembered a song:

Long Hair, Long Hair,

I was short of guns,

and you brought us many.

Long Hair, Long Hair,

I was short of horses,

and you brought us many.

As late as the 1920s, elderly Cheyennes said that two southern Cheyenne women had come upon the body of Custer. He had been shot in the head and in the side. They recognized Custer from the Battle of the Washita in 1868, and had seen him up close the following spring when he had come to make peace with Stone Forehead and smoked with the chiefs in the lodge of the Arrow Keeper. There Custer had promised never again to fight the Cheyennes, and Stone Forehead, to hold him to his promise, had emptied the ashes from the pipe onto Custer’s boots while the general, all unknowing, sat directly beneath the Sacred Arrows that pledged him to tell the truth.

It was said that these two women were relatives of Mo-nah-se-tah, a Cheyenne girl whose father Custer’s men had killed at the Washita. Many believed that Mo-nah-se-tah had been Custer’s lover for a time. No matter how brief, this would have been considered a marriage according to Indian custom. On the hill at the Little Bighorn, it was told, the two southern Cheyenne women stopped some Sioux men who were going to cut up Custer’s body. “He is a relative of ours,” they said. The Sioux men went away.

Every Cheyenne woman routinely carried a sewing awl in a leather sheath decorated with beads or porcupine quills. The awl was used daily, for sewing clothing or lodge covers, and perhaps most frequently for keeping moccasins in repair. Now the southern Cheyenne women took their awls and pushed them deep into the ears of the man they believed to be Custer. He had not listened to Stone Forehead, they said. He had broken his promise not to fight the Cheyenne anymore. Now, they said, his hearing would be improved.

Thomas Powers is the author of eight previous books. Aaron Huey has spent six years documenting life among the Oglala Sioux on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

Adapted from The Killing of Crazy Horse, by Thomas Powers. Copyright © 2010. With the permission of the publisher, Alfred A. Knopf.