How the Emancipation Proclamation Came to Be Signed

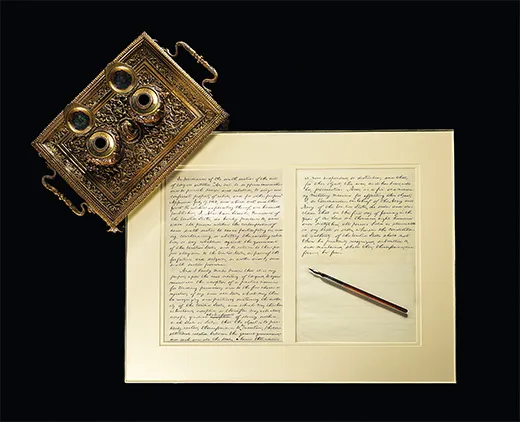

The pen, inkwell and one copy of the document that freed the slaves are photographed together for the first time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/National-Treasure-Emancipation-Proclamation-631.jpg)

On July 20, 1862, John Hay, Lincoln’s private secretary, predicted in a letter that the president “will not conserve slavery much longer.” Two days later, Lincoln, wearing his familiar dark frock coat and speaking in measured tones, convened his cabinet in his cramped White House office, upstairs in the East Wing. He had, he said, “dwelt much and long on the subject” of slavery. Lincoln then read aloud a 325-word first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, intended to free slaves in Confederate areas not under United States authority.

Salmon P. Chase, secretary of the treasury, stated that he would give the measure his “cordial support.” Secretary of State William Henry Seward, however, advised delay until a “more auspicious period” when demonstrable momentum on the battlefield had been achieved by the Union.

Lincoln concurred, awaiting a propitious moment to announce his decision and continuing to revise the document. At noon on Monday, September 22, Lincoln again gathered the cabinet at the White House. Union troops had stopped the Confederate Army advance into Maryland at the Battle of Antietam on September 17. The president saw that he now operated from a position of greater strength. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles later observed that Lincoln “remarked that he had made a vow, a covenant, that if God gave us the victory...it was his duty to move forward in the cause of emancipation.”

The meeting soon adjourned, and the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued that day. “It is my last trump card, Judge,” he told his supporter Edwards Pierrepont, a New York attorney and jurist. “If that don’t do, we must give up.”

One hundred-fifty years later, three numinous artifacts associated with the epochal event have been photographed together for the first time. An inkwell—according to the claims of a Union officer, Maj. Thomas T. Eckert, used by Lincoln to work on “an order giving freedom to the slaves of the South” as the president sat awaiting news in the telegraph room of the War Department—is in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The first draft of the Proclamation resides at the Library of Congress. And the pen with which Lincoln signed the final document belongs to the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Yet even when Lincoln acted decisively on September 22, he announced that he would sign the act only 100 days hence, affording additional time for the Northern public to prepare for his shift in policy. The New York Times opined that “There has been no more far reaching document ever issued since the foundation of this government.” The Illinois State Register in Springfield, Lincoln’s hometown, warned darkly of “the setting aside of our national Constitution, and, in all human probability, the permanent disruption of the republic.”

One of the weightiest questions was whether significant numbers of Union soldiers would refuse to fight in a war whose purpose was now not only to preserve the Union but also to end slavery. “How Will the Army Like the Proclamation?” trumpeted a headline in the New York Tribune. Yet the Army would stand firm.

During that 100-day interlude, Lincoln’s own thinking evolved. He made alterations in the document that included striking out language advocating colonization of former slaves to Africa or Central America. He opened the ranks of the Army to blacks, who until then had served only in the Navy. Lincoln also added a line that reflected his deepest convictions. The Proclamation, he said, was “sincerely believed to be an act of justice.”

The edict, says NMAH curator Harry Rubenstein, “transforms the nation. Lincoln recognized it and everybody at the moment recognized it. We were a slave society, whether you were in the North or the South. Following this, there was no going back.”

When the moment arrived for signing the Proclamation—on January 1, 1863—Lincoln’s schedule had already been crowded. His New Year’s reception had begun at 11 a.m. For three hours, the president greeted officers, diplomats, politicians and the public. Only then did he return to his study. But as he reached for his steel pen, his hand trembled. Almost imperceptibly, Lincoln hesitated. “Three hours of hand-shaking is not calculated to improve a man’s chirography,” he said later that evening. He certainly did not want anyone to think that his signature might appear tremulous because he harbored uncertainty about his action. Lincoln calmed himself, signed his name with a steady hand, looked up, and said, “That will do.” Slaves in Confederate areas not under Union military control were decreed to be “forever free.”

Ultimately, it was Lincoln who declared his own verdict on his legacy when he affixed his signature that afternoon in 1863. “I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right,” he said, “than I do in signing this paper. If my name goes into history, it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”