The Iroquois Theater Disaster Killed Hundreds and Changed Fire Safety Forever

The deadly conflagration ushered in a series of reforms that are still visible today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/e6/60e60c76-3972-44fe-8f7f-2eae44ae1096/exterioriroquois-wr.jpg)

On a chilly Chicago winter day—December 30, 1903 —the ornate, five-week-old Iroquois Theater was filled with teachers, mothers and children enjoying their holiday break. They had gathered to see Mr. Bluebeard, an over-the-top musical comedy starring Chicago native Eddie Foy. It featured scenes from around the world, actors masquerading as animals and a suspended ballerina. It was a spectacular production fit for a rapidly growing and increasingly prominent city. The eager crowd of more than 1700 patrons could not have suspected that almost one-third of them would perish that afternoon in “a calamity which…bereft hundreds of homes of their loved ones and made Chicago the most unhappy city on the face of the earth,” as The Great Chicago Theater Disaster would later recount. The tragedy would be a wake-up call to the city—and the nation—and lead to reforms in the way public spaces took responsibility for the safety of their patrons.

As the show began its second act at 3:15 that afternoon, a spark from a stage light ignited nearby drapery. Attempts to stamp out the fire with a primitive retardant did nothing to halt its spread across the flammable decorative backdrops. Foy, dressed in drag for his next scene, attempted to calm the increasingly agitated audience. He ordered the orchestra to continue playing as stagehands made futile attempts to lower a supposedly flame-retardant curtain, but it snagged.

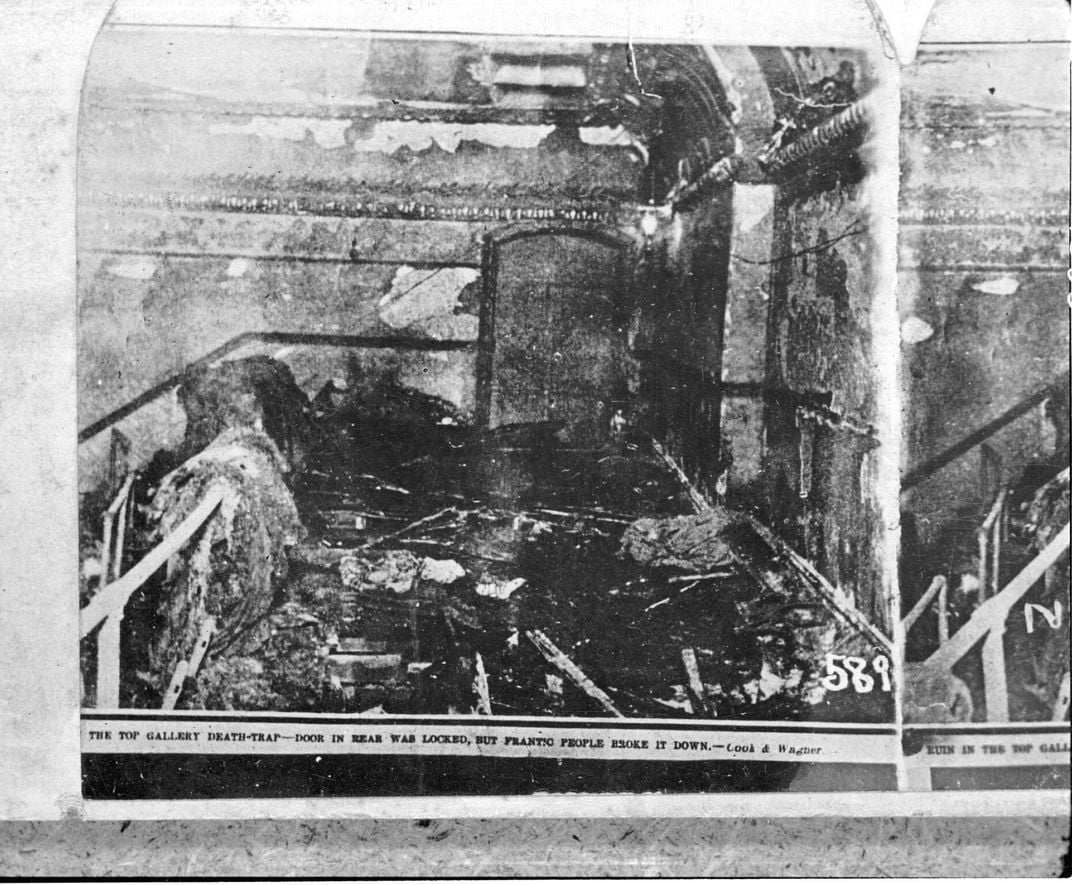

It was soon apparent that the fire could not be contained. Audience members bolted from their seats toward what few exit doors they could find, but most were obscured by curtains. They were further stymied by metal accordion gates, firmly locked to keep those in upper levels from sneaking down to pricier seats during intermissions. The terrified patrons – an estimated 1,700 with many more standing ticket holders clogging the aisles - were funneling through scant few chokepoints. Quickly the scene had changed “from mimicry to tragedy,” as one survivor said. Watching from the stage, Foy wrote in his memoirs, he saw in the upper levels a “mad, animal-like stampede – their screams, groans and snarls, the scuffle of thousands of feet and bodies grinding against bodies merging into a crescendo half-wail, half-roar.”

As cast members realized the peril they were in, they opened a rear stage door to escape (the ballerina, trapped by her rigging, would not make it out of the theater alive). The backdraft from the open door caused a sudden ball of flame to explode through the theater, instantly killing many in the virtually inescapable balconies. It was powerful enough to blow at least one exit door open, aiding those frantically trying to work the unfamiliar locks. A few were fortunate enough to find an upper-level fire escape, only to realize it lacked an exterior ladder down to the ground. Workmen in a building across the alley cantilevered planks to create a heart-stopping makeshift bridge, saving a handful of patrons after the first two who attempted it slipped and fell to their deaths.

Within a few moments, hundreds of bodies, unsuccessful in finding an egress began piling up inside the theater. They had died before firefighters arrived on the scene. The Great Chicago Fire Disaster described what awaited them as worse than that “pictured in the mind of Dante in his vision of the inferno.”

The diner next door was transformed into both morgue and hospital as doctors tried to find living victims in a sea of charred remains. Panicked family and friends soon began descending on the restaurant to see if loved ones had somehow escaped. As word of the staggering death toll spread, the city would be overcome by a state of collective mourning.

The loss of life struck at the heart of Chicago’s upper-middle class society. They were, as The Great Chicago Theater Disaster described them “Chicago’s elect, the wives and children of its most prosperous business men and the flower of local society.” Some had even traveled in by train from nearby cities to enjoy the holiday atmosphere in the heart of downtown Chicago. Their deaths would galvanize the city. “If you have more wealthy, social people that die in an Iroquois theater fire versus the everyday middle-class people unfortunately those are sometimes things that get more attention than they should,” says Robert Solomon of the National Fire Protection Association.

But shock and grief quickly gave rise to outrage. The opulent theater had been advertised as “absolutely fireproof.” How could hundreds of souls – mostly women and children - perish so rapidly? Who was responsible?

Days later, the Chicago Tribune ran a list of regulations that had been flouted by the Iroquois, including the lack of an adequate fire alarm, automatic sprinklers, marked exits, or suitable fire extinguishing devices. Even the two large flues on the rooftop where the smoke and flame could have vented out were boarded shut. The newspaper called for action: “The only atonement that can be made to these hapless victims of negligence is to make the theaters of Chicago absolutely safe, so that none others may meet their fate.”

The task of proving culpability, however, became hopelessly complex. The myriad problems that day turned into an algebra of blame—so many had failed to carry out their duties that no one source could be concretely assigned sole responsibility. An official inquest focused on the theater owners, the architect, and city officials, who in turn were quick to point fingers, including at the victims themselves. The owners, Will J. Davis and Harry J. Powers, issued a statement in the Tribune blaming the audience for panicking despite being “admonished…to be calm and avoid any rush”; the architect insisted there were “ample” exits had people not become “panic stricken and stunned.”

“Everybody afterward was washing their hands of responsibility. It was such a total loss of life they didn’t want to be connected to it if possible,” said journalist Nat Brandt, author of Chicago Death Trap. An underlying culture of complacency did nothing to narrow things down. “You’re also talking about a city that was notorious at that time with regard to laws and doing what you were supposed to do, and patronage and payoffs,” said Brandt. While a direct link to corruption was never proven in court, the indifference of city officials to known violations contributed to the fact that the theater received only a cursory safety inspection before opening to the public weeks earlier. Although construction had run behind schedule, the theater owners rushed to open it before the lucrative holiday season. But the problems that plagued theaters throughout the city were not unknown. Concerned about pervasive safety violations, Mayor Carter Harrison ordered a review of all theaters just months earlier, but lack of enthusiasm from city officials meant the investigations had petered out.

After numerous investigations, reams of testimony, and three years of legal wrangling, no one was ever held criminally liable. Numerous lawsuits from victims’ families died out, becoming too expensive to maintain against multiple defendants, including the theater owners and city. Davis was tried, but not convicted. In the end, a batch of payouts to families from the construction company that had built the theater was the only concrete liability.

But the Iroquois fire, which was one of a series of major headline-making fires in the early 1900s, was a catalyst for systemic changes aimed at preventing another fire of similar magnitude. “The school fires and the theater fires and the opera house fires – those were the ones that in a matter of 15-20 minutes you’ve got 100 people, 200, 300, 400 people - that many people dying that quickly. It’s like a lot of things in society where there’s a tipping point, the frequency becomes too much and the number of people dying becomes too much,” says Solomon. “Then you ultimately have to get policymakers and politicians to take action.”

The fire forced Chicago to take a hard look at how they regulated large public spaces in the booming city. “How much of that was because they had flouted the building codes and how much of it was that the building codes didn’t go far enough?” says John Russick of the Chicago Historical Society. “…[there was] a fair amount of ‘our buildings don’t protect us and we need to do more to them.’ It wouldn’t have been enough even if the building codes had been followed—a lot of people would have died in the Iroquois Theater fire.”

Within days, the city shuttered all theaters in its jurisdiction until they could be inspected and repaired to standard, and national headlines forced other cities across the country to subject their own theaters to similar scrutiny. Within weeks, Chicago’s city council passed a new building ordinance by an overwhelming majority that compelled structural changes including new standards for aisles and exits, the use of fireproofing solution on scenery, connected fire alarms, limits on occupancy, the elimination of “standing” tickets, changes to sprinkler requirements, and rules for rooftop flues (like those nailed shut in the Iroquois).

Among the enduring changes were the stipulations pertaining to the lighting of exits, aisles and corridors, including the requirement that “a red light to be kept burning over the exits” during performances. This echoed the words of an electrical engineer who had advocated for signs to be illuminated by “a source of light independent of the theater lighting system,” a critical point since the Iroquois’ electricity had gone out during the blaze. An April 1904 edition of Western Electrician highlighted the adoption of “exit lights [which] are also supplemented by sperm-oil lamps” in the event that “the current supply is interrupted.” Although technology has evolved, signs like these were the forerunners to the glowing red exit signs ubiquitous in modern theaters.

The Iroquois fire also inspired the development of “panic bars” found on emergency exits. Carl Prinzler, a hardware salesman who had originally planned to attend the performance of Mr. Bluebeard on the day of the fire, went on to work with his colleagues to invent the crash bar mechanism on doors that prevented entry from the outside—the major concern of ticket sellers—but could be easily opened under duress, and generations of that first design have been used in public buildings for over a century.

While new laws and innovations would make theaters safer, they continued to depend on highly visible tragedies influencing the least tangible and most variable of factors: human behavior. “Unless there’s vigilance and diligence, even things on the books can be ignored by both the builder or the architect or the inspector or the building owner,” said Russick. “There are a lot of people that need to be in compliance and do their part in order to have the kind of world where people are protected.” This may preclude any building from being “absolutely fireproof,” but theaters today reflect the cumulative and painful lessons learned in tragedies like the Iroquois Theater fire.