How Three Doughboys Experienced the Last Days of World War I

The end of the war was a welcome reprieve for these three American soldiers, eager to return home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/d1/42d1d29b-978a-49f3-882d-90d6880d08e7/portraits.jpg)

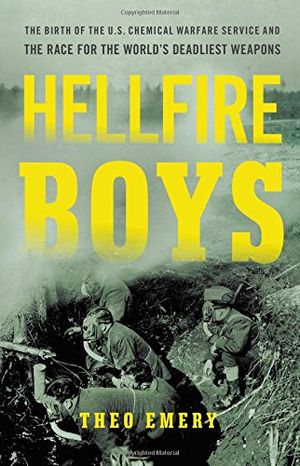

Sgt. Harold J. Higginbottom. 2nd Lt. Thomas Jabine. Brigadier General Amos A. Fries. When these three U.S. servicemen heard the news about the armistice ending the First World War, they were in three very different circumstances. Their stories, told below in an excerpt from Theo Emery’s Hellfire Boys: The Birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service and the Race for the World’s Deadliest Weapons, offer a window into how the war was still running hot until its very last hours. While Emery’s book details the rapid research and development of chemical weapons in the U.S. during the war and the young men in the First Gas Regiment, it also connects readers to the seemingly abstract lives of 100 years ago.

***********

Daylight was fading on November 8 as Harold “Higgie” Higginbottom and his platoon started through the woods in the Argonne. Branches slapped their faces as they pushed through the undergrowth. Their packs were heavy, and it began to rain. There was no path, no road, just a compass guiding them in the dark. Whispers about an armistice had reached all the way to the front. “There was a rumor around today that peace had been declared,” Higgie wrote in his journal. If there was any truth to it, he had yet to see it. Rumors of peace or no, Company B still had a show to carry out. Its next attack was some 15 miles to the north, in an exposed spot across the Meuse River from where the Germans had withdrawn. The trucks had brought them partway, but shells were falling on the road, so the men had to get out of the open and hike undercover.

They waded across brooks and swamps and slithered down hills, cursing as they went. Some of the men kept asking the new lieutenant in charge where they were going. One man fell down twice and had trouble getting back up; the other men had to drag him to his feet. They found a road; the mud was knee deep. Arching German flares seemed to be directly overhead, and even though the men knew that the Meuse River lay between the armies, they wondered if they had somehow blundered into enemy territory. Water soaked through Higgie’s boots and socks. When they finally stopped for the night, the undergrowth was so dense it was impossible to camp, so Higgie just rolled himself up in his tent as best he could and huddled on the hillside.

Hellfire Boys: The Birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service and the Race for the World’s Deadliest Weapons

As gas attacks began to mark the heaviest and most devastating battles, these brave and brilliant men were on the front lines, racing against the clock-and the Germans-to protect, develop, and unleash the latest weapons of mass destruction.

Higgie awoke the next morning in a pool of water. He jumped to his feet, cursing. Mud was everywhere, but at least in daylight they could see their positions and where they were going. He carried bombs up to the advance position, returned for coffee, then made another carry, sliding in the mud. More of the company joined them in carrying mortars up to the front. Higgie had begun to feel better—the hike had warmed him up, and he had found a swell place to camp that night, a spot nestled among trees felled by the Germans. Everyone was cold and wet and caked in mud, but at least Higgie had found a dry spot. When he went to bed, the air was so cold that he and another man kept warm by hugging each other all night.

When the frigid morning of November 10 arrived, some of the men lit pieces of paper and tucked them into their frozen boots to thaw them out. Higgie made hot coffee and spread his blankets out to dry. Late that night, the 177th Brigade was going to ford the Meuse, and Higgie’s company was to fire a smoke screen to draw fire away from the advancing infantry.

Elsewhere, the Hellfire Regiment had other shows. At 4:00 p.m., Company A shot phosgene at a machine-gun position, forcing the Germans to flee. That night, Company D fired thermite shells over German machine-gun positions about six miles north of Higgie and put up a smoke screen that allowed the Fourth Infantry to cross the Meuse. Higgie rolled himself up in blankets to sleep before the show late that night. But his show was canceled, the infantry forded the river without the smoke screen, and Higgie couldn’t have been happier. He swaddled himself back up in his blanket and went back to bed.

Higgie was dead asleep when a private named Charles Stemmerman shook him awake at 4:00 a.m. on November 11. Shells were falling again, and he wanted Higgie to take cover deeper in the forest. Their lieutenant and sergeant had already retreated into the woods. Higgie shrugged off the warning. If the shells got closer, he would move, he told the private. Then he turned over and went back to sleep.

He awoke again around 8:00 a.m. The early morning shell barrage had ended. In the light of morning, an impenetrable fog blanketed the forest, so dense that he couldn’t see more than ten feet around him. He got up to make breakfast and prepared for the morning show, a mortar attack with thermite.

Then the lieutenant appeared through the mist with the best news Higgie had heard in a long time. All guns would stop firing at 11 o’clock. The Germans had agreed to the Armistice terms. The war had ended. Higgie thought in disbelief that maybe the lieutenant was joking. It seemed too good to be true. He rolled up his pack and retreated deeper into the woods, just to be on the safe side. They had gone through so much, had seen so many things that he would have thought impossible, that he wasn’t going to take any chances now.

***********

To the southeast, Tom Jabine’s old Company C was preparing a thermite attack on a German battalion at Remoiville. Zero hour was 10:30 a.m. With 15 minutes to go, the men saw movement across the line. The company watched warily as 100 German soldiers stood up in plain view. As they got to their feet, they thrust their hands into their pockets—a gesture of surrender. An officer clambered up out of the German trench. The Americans watched as he crossed no-man’s-land. The armistice had been signed, the German officer said, and asked that the attack be canceled. Suspecting a trap, the Americans suspended the operation but held their positions, just in case. Minutes later, word arrived from the 11th Infantry. It was true: The armistice had been signed. The war was over.

Hundreds of miles away, the sound of whistles and church bells reached Tom Jabine as he lay in his hospital bed in the base in Nantes, where he had arrived a few days earlier. For days after a mustard shell detonated in the doorway of his dugout in October, he had lain in a hospital bed in Langres, inflamed eyes swollen shut, throat and lungs burning. After a time, the bandages had come off, and he could finally see again. He still couldn’t read, but even if he could, letters from home had not followed him to the field hospital. The army had not yet sent official word about his injuries, but after his letters home abruptly stopped, his family back in Yonkers must have feared the worst.

In early November, the army transferred him to the base hospital in Nantes. Not a single letter had reached Tom since his injury. He could walk, but his eyes still pained him, and it was difficult to write. More than three weeks after he was gassed, he had been finally able to pick up a pen and write a brief letter to his mother. “I got a slight dose of Fritz’s gas which sent me to the hospital. It was in the battle of the Argonne Forest near Verdun. Well I have been in the hospital ever since and getting a little better every day.”

When the pealing from the town spires reached his ears, he reached for pen and paper to write to his mother again. “The good news has come that the armistice has been signed and the fighting stopped. We all hope this means the end of the war and I guess it does. It is hard to believe it is true, but I for one am thankful it is so. When we came over I never expected to see this day so soon if I ever saw it at all,” he wrote. Now, perhaps, he could rejoin his company and go home. “That seems too good to be true but I hope it won’t be long.”

***********

Amos Fries was at general headquarters in Chaumont when the news arrived. Later in the day, he drove into Paris in his Cadillac. Shells had fallen just days earlier; now the city erupted in celebration. After four years of bloodshed, euphoria spilled through the city. As Fries waited in his car, a young schoolgirl wearing a blue cape and a hood jumped up on the running board. She stuck her head in the open window and blurted to Fries with glee: “La guerre est fini!” — The war is over! — and then ran on. Of all the sights that day, that was the one Fries recounted in his letter home the next day. “Somehow that sight and those sweet childish words sum up more eloquently than any oration the feeling of France since yesterday at 11 a.m.”

As the city roiled in jubilation, a splitting headache sent Fries to bed early. The festivities continued the next day; Fries celebrated with a golf game, then dinner in the evening. “Our war work is done, our reconstruction and peace work looms large ahead. When will I get home? ‘When will we get home?’ is the question on the lips of hundreds of thousands.”

***********

Like the turn of the tide, the movement of the American army in the Argonne stopped and reversed, and the men of the gas regiment began retreating south. Hours earlier, the land Higginbottom walked on had been a shooting gallery in a firestorm. Now silence fell over the blasted countryside. For Higgie, the stillness was disquieting after months of earthshaking detonations. He still couldn’t believe the end had come. The company loaded packs on a truck and started hiking to Nouart, about 14 miles south. They arrived in the village at about 5:30 p.m. Higgie went to bed not long after eating. He felt ill after days of unending stress and toil. But he couldn’t sleep. As he lay in the dark with the quiet pressing in around him, he realized that he missed the noise of the guns.

He awoke in the morning to the same eerie stillness. After breakfast, he threw his rolled-up pack on a truck and began the 20-mile hike back to Montfaucon. Everything seemed so different now as he retraced his steps. Everything was at a standstill. Nobody knew what to make of things. They arrived at Montfaucon after dark. The moon was bright and the air very cold with a fierce wind blowing. The men set up pup tents on the hilltop, where the shattered ruins of the village overlooked the valley. A month before, German planes had bombed the company as they camped in the lowlands just west of Montfaucon, scattering men and lighting up the encampment with bombs. For months, open fires had been forbidden at the front, to keep the troops invisible in the dark. Now, as Higgie sat on the moonlit hilltop, hundreds of campfires blazed in the valley below.

Excerpted from Hellfire Boys: The Birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service and the Race for the World’s Deadliest Weapons. Copyright © 2017 by Theo Emery. Used with permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.