How Thurgood Marshall Paved the Road to ‘Brown v. Board of Education’

A case in Texas offered a chance for the prosecutor and future Supreme Court justice to test the legality of segregation

:focal(1750x1400:1751x1401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/de/ffde142a-63db-45fa-935f-e1e10401fb3d/gettyimages-515585588.png)

To cover the 400 years of Black America, we divided Four Hundred Souls into ten sections, each covering 40 years. The following essay from Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, covers the five-year-span from 1949 to 1954. Ifill describes the long campaign of desegregation cases brought by Thurgood Marshall, then president of the Legal Defense Fund, focusing on a suit that arose out of Hearne, Texas. World War II and its aftermath exposed the contrast to fighting fascism abroad while the system of Jim Crow governed the American South. The school system of Hearne, Texas, produced a stark example of this contradiction when, following a fire that destroyed the black high school, the white school superintendent decided that the barracks that once housed German prisoners of war should become the new segregated school. Ifill’s essay captures the long struggle for educational equality in the United States. — Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain

In 1948, U.S. officials vigorously prosecuted German war criminals in Nuremberg for enforcing anti-Semitic policies, practices and laws that advanced a theory of ethnic and religious inferiority of Jews. At the same time, state officials across the American South were enforcing segregationist policies, practices and laws that advanced a theory of white supremacy and the racial inferiority of African Americans, undisturbed by the federal government.

In the small town of Hearne, Texas, starting in the fall of 1947, the contrast between the U.S. fight against Nazism abroad and its embrace of a rigid racial caste system at home was dramatized in a battle over segregated schools. The standoff between African American parents in Hearne and the local white school superintendent drew the attention of attorney Thurgood Marshall. Just eight years earlier the brilliant and determined young African American lawyer from Baltimore had founded the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF). Marshall became the LDF’s first president and its director-counsel in 1940. Seventy-three years later, I became the LDF’s seventh president and director-counsel.

The story of LDF’s brilliant strategy to successfully challenge the constitutionality of racial segregation has been documented and chronicled in multiple books and articles. The strategy culminated in Brown v. Board of Education, a monumental 1954 landmark Supreme Court decision that literally changed the course of 20th-century America. The Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, decided that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and deprive black children of the constitutional right to equal protection of the laws. The decision cracked the load-bearing wall of legal segregation. Within ten years, the principles vindicated in Brown were successfully deployed to challenge segregation laws in the United States.

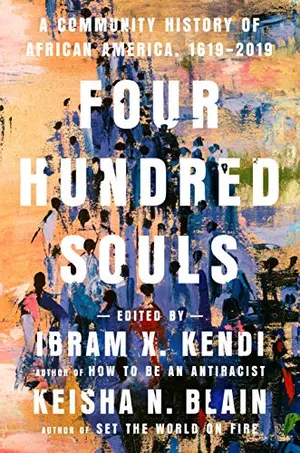

Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019

This is a history that illuminates our past and gives us new ways of thinking about our future, written by the most vital and essential voices of our present.

The rather unknown story that unfolded in Hearne, Texas, captures the historical significance of Brown. Black parents were powerfully affected by the contrast between the U.S. stance against Nazis on the global stage and the embrace of Jim Crow at home. Their postwar ambitions for their children ran headlong into the determination of Southern whites to reinforce segregation. In communities around the South, Black parents sought and received the assistance of local NAACP lawyers to challenge the absence of school facilities for their children, or the substandard educational facilities and investment in Black schools.

In Hearne the challenge was initiated by C. G. Jennings, the stepfather of 13-year-old twins, Doris Raye and Doris Faye Jennings. In August 1947, he tried to register his daughters at the white high school. His request was refused, and he engaged local counsel.

A few weeks later, in September 1947, African American parents initiated a mass boycott. Maceo Smith, who led the NAACP in Dallas, contacted Marshall about the situation in Hearne.

A year earlier, the Blackshear School, the high school designated for black students, had burned down. No one expected the black students to now attend the nearby white school due to a Texas law segregating students. The school superintendent announced that $300,000 would be devoted to the construction of a new school for black students, and a $70,000 bond issue was placed on the ballot. Although black children outnumbered white students in Hearne, the physical plant of the existing high school for white students was estimated to have a value of $3.5 million. The building that would be haphazardly renovated into the “new” black high school was, in fact, the dilapidated barracks that had just recently housed German soldiers during the war.

When black parents learned about the city’s plans, they felt compelled to take matters into their own hands. According to reports in the local African American newspaper, “these buildings were sawed in half, dragged to the school location, and joined together with no apparent regard for physical beauty or concealing their prison camp appearance.” The complaint later filed by parents in Jennings v. Hearne Independent School District further described the school as “a fire hazard,” “overcrowded and . . . unfurnished with modern equipment,” and with “inadequate lighting.” All in all, the black parents deemed the building “unsafe for occupancy,” and the indignity of educating their children in a prisoner of war barracks was an insult too ugly to be borne.

White officials and local newspapers disparaged the parents’ school boycott and the Jennings suit as an attempt by the NAACP to “stir up trouble.” On September 28, Marshall—who recognized the importance of challenging media distortions to his litigation efforts—fired back at the editorial board of The Dallas Morning News with a lengthy letter.

As African American parents in Hearne kept their children home from school, 100 miles away in Houston, black schoolteacher Henry Eman Doyle was the sole law student registered at Texas State University for Negroes, a hastily organized three-room “school” created by the State of Texas after Marshall won a discrimination case brought on behalf of Heman Sweatt, a black student who had been barred from registering at the University of Texas Law School. The three-room school, located in the basement of the state capitol, was the state’s attempt to comply with the Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” doctrine that required states to provide a public law school for black students if they excluded black students from flagship public law schools.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/f8/e5f87d3b-b558-43b1-a6a6-e6f599dbd8e3/gettyimages-640491199.jpg)

Marshall again challenged the state, and in 1950, the Supreme Court would find that Texas’s crude attempts at equality were in vain, and that at least in the area of law education, separate could not be equal. The decision is widely regarded as the final case that set the successful stage for the frontal attack on segregation that became Brown v. Board of Education.

Meanwhile, some federal judges found the courage to defy Southern mores and uphold the constitutional guarantee of equal protection. In South Carolina, federal court judge Julius Waties Waring, the scion of a respected Charleston family with deep Confederate roots, issued a series of unexpected decisions in cases tried by Marshall that suggested that federal judges might play a role in protecting civil rights. Waring’s searing, powerful dissent in Briggs v. Elliot, the South Carolina Brown case, became the template for the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown. Here Judge Waring first articulated the concept that “segregation is per se inequality”—a full-on rebuke of Plessy v. Ferguson that Chief Justice Warren later paraphrased in Brown.

Other civil rights lawyers, and the African American parents they represented, were also emboldened after World War II. And it was their energy and uncompromising demands that shifted the landscape. By 1951, African American students were making their own demands. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, 16-year-old Barbara Johns led her classmates at Moton High School in a walkout and boycott of their segregated school. Her action prodded Marshall and the LDF lawyers to file Davis v. Prince Edward County, Virginia, one of the four Brown cases.

Back in Hearne, by the time African American parents began organizing to challenge the dilapidated “new” high school for their children, Marshall already had his hands full with cases, all of which would become landmarks in their own right. The case was dismissed at the district court level and reaffirmed the principle of segregation in Texas schools.

The Hearne lawsuit was one of a cadre of small, unsuccessful cases extending back to Marshall’s late 1930s schoolteacher-pay-equality cases in Maryland and Virginia. But these cases played a powerful role in shaping the thinking of LDF lawyers about what was possible in their litigation challenging Jim Crow. And it powerfully demonstrated the civil rights challenge confronting the United States in those early postwar years.

As Thurgood Marshall wrote in his 1948 letter to the editors of The Dallas Morning News, “I think that before this country takes up the position that I must demand complete equality of right of citizens of all other countries throughout the world, we must first demonstrate our good faith by showing that in this country our Negro Americans are recognized as full citizens with complete equality.”

From the book FOUR HUNDRED SOULS: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain. "The road to Brown v. Board of Education" by Sherrilyn Ifill © 2021 Sherrilyn Ifill.

Published by permission of One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.