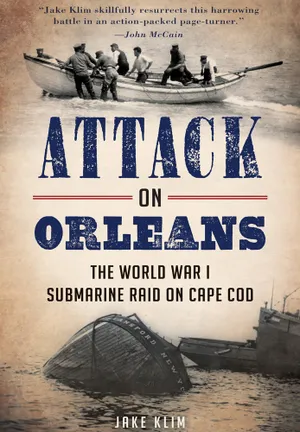

How a Tiny Cape Cod Town Survived World War I’s Only Attack on American Soil

A century ago, a German U-boat fired at five vessels and a Massachusetts beach before slinking back out to sea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/67/d667ef22-ba98-4c71-b70b-0fdb9c6d3ffc/001.jpg)

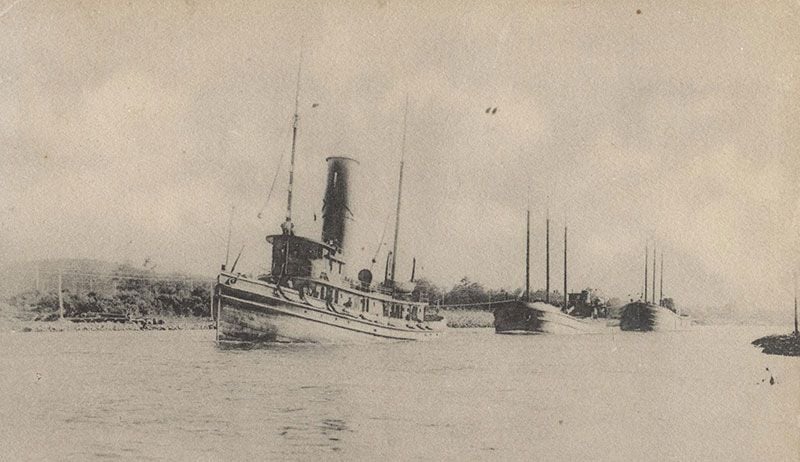

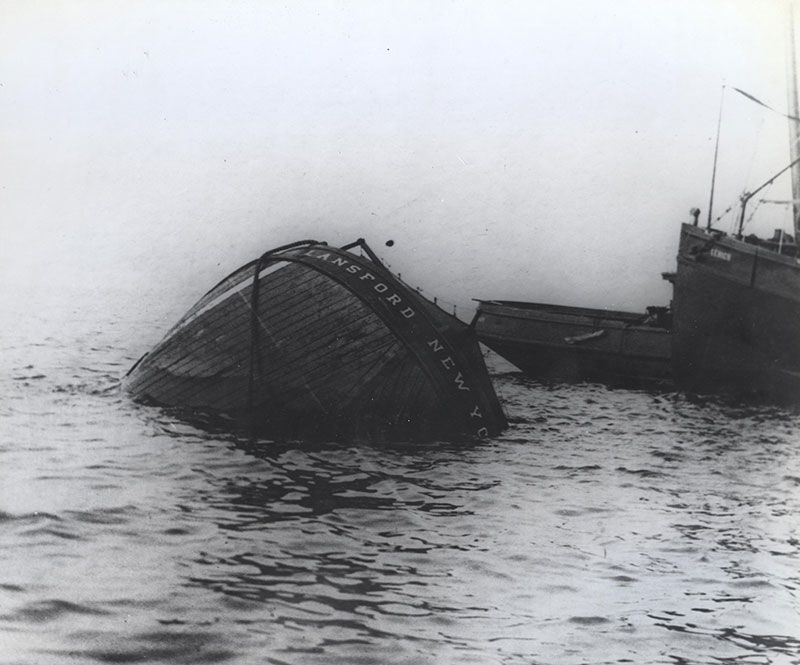

July 21, 1918, dawned hot and hazy in Orleans, Massachusetts. Three miles offshore, the Perth Amboy, a 120-foot steel tugboat, chugged south along the outer arm of Cape Cod en route to the Virginia Capes with four barges in tow: the Lansford, Barge 766, Barge 703 and Barge 740. The five vessels carried a total of 32 people, including four women and five children.

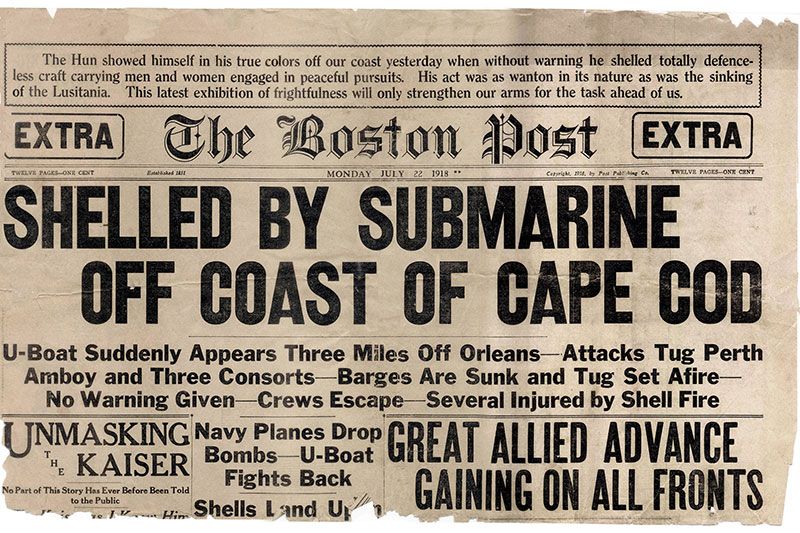

Just before 10:30 a.m., a deckhand on the Perth Amboy was startled by the sight of something white skipping through the water. The mysterious object passed wide of the tug, to the stern. Moments later, that same something crashed into the beach, sending sand high into the air in every direction. A great thunderous roar ripped through the quiet summer morning in Orleans, but those living along the beach were confused—no one was expecting rain. Though residents did not know it at the time, the town of Orleans was making history: the projectile that landed on the beach was the only fire the American mainland would receive during the First World War.

The German U-156 emerged from the haze and inched closer to the tug and, for reasons that largely remain speculative, proceeded to send volley after volley in the direction of the five ships.

The Perth Amboy’s captain, James Tapley, had been asleep. At the sound of the first blast, he staggered out on deck and saw what looked like an enormous submarine.

“This, I was sure, was the source of the trouble,” Tapley quipped in a letter he wrote in 1936.

Tapley braced for impact, but most of the U-boat’s shells missed their target, instead pounding the ocean around the Perth Amboy sending fountains of water up in to the sky.

“I never saw a more glaring example of rotten marksmanship,” Captain Tapley told the Boston Daily Globe. “Shots went wild repeatedly and but few that were fired scored hits.”

However, one of the shells fired from the sub’s dual 5.9-inch deck guns crashed into the tug’s pilothouse. The helmsman steering the ship, John Bogovich, felt the structure partially collapse on top of him. Stunned and shaken, he dragged his broken body out of the debris and looked over his injuries, which included jagged wounds above his elbow.

The captain swallowed hard. He knew it was only a matter of time until the sub scored another hit, possibly a knockout.

“We were powerless against such an enemy,” Tapley said. “All that we could do was to stand there and take what they sent us.”

Ultimately, Captain Tapley ordered his crew to abandon ship.

From 1914 to 1918, Germany constructed nearly 400 submarines, but only seven were long-range cruisers that could sail from one side of the Atlantic to the other, pushing the limits to what submersibles were capable of during the First World War. These specialized ships, the U.S. Navy warned, “May appear in American waters without warning,” and cautioned that the “bombardment of coastal towns may also be done.”

During the last summer of the First World War, Germany finally unleashed her infamous U-boats against the eastern seaboard of the United States. In June 1918, one of these long-range cruisers, the U-151, emerged from the deep in the waters off Virginia and harassed American shipping throughout the mid-Atlantic. In a 24-hour period, the U-151 sank seven merchant schooners, one of the greatest single-day achievements of any U-boat during the entire war. One month later, a second submarine, the U-156, surfaced south of Long Island and sowed the ocean with mines, subsequently sinking the armored cruiser U.S.S. San Diego and killing six American sailors. Converging from air and sea alike, ships and airplanes worked in concert to locate and destroy the U-156, but the submarine had escaped.

Where the raider would appear next was anyone’s guess.

Back on shore in Orleans, Number One Surfman William Moore was on watch in the tower at U.S. Coast Guard Station Number 40. He scanned the horizon as he always did: constantly looking for ships in peril, but with the ocean so tranquil, it seemed highly unlikely that he and his cohorts would have any missions that day. Suddenly, an explosion ripped through the quiet Sunday morning. According to a 1938 article in the Barnstable Patriot, Moore climbed down the tower and alerted the station’s keeper, Captain Robert Pierce, that there were “heavy guns firing on a tow of barges east, northeast from the station.” Pierce, a seasoned seaman who had worked as a lifesaver for nearly 30 years, had never heard anything like this before in his life. He instinctively ordered a surfboat dragged out of the station, but as evidence of a submarine attack offshore became increasingly clear, the keeper began to contemplate what, exactly, he should do next. There was little in their surf station to combat the arsenal of a German U-boat. “That was quite ridiculous to our minds,” one of the surfmen noted in a 1968 interview recorded by Cape Cod historians. “Few at the station ever imagined a submarine attack.”

Meanwhile, curious townspeople who had heard the commotion going on offshore began to spill out of their homes and descend on the beach. Shells skipped across the water and soared through the sky, terrifying the residents of Orleans.

“All seemed to think that the dreaded, expected…bombardment of the Cape had started,” one local said, according to the 2006 book Massachusetts Disasters: True Stories of Tragedy and Survival, adding, “Cape Cod has met the German submarine menace and is not afraid.”

Whether or not the town was actually equipped to repel an invasion was debatable, but one thing was certain: Orleans was under attack.

At 10:40 a.m. Captain Pierce called the Chatham Naval Air Station, located seven miles to the south. The station’s new flying boats were equipped with bombs that packed a much bigger punch than anything the lifesavers had in their small surf station. It would take nearly 10 minutes to transmit, so Pierce’s message, recorded in Richard Crisp’s 1922 book A History of the United States Coast Guard in the World War, was simple and to the point:

“Submarine sighted. Tug and three barges being fired on, and one is sinking three miles off Coast Guard Station 40.” [There were, in fact, four barges, not three.]

Pierce slammed the phone back on the receiver and rushed to join Moore and others who were in the process of launching the lifeboat. Pierce boarded last, giving the boat one last heave off the beach, and guided the craft towards the vessels in distress. Pierce recalled the lifesaver’s creed: “You have to go, but you don’t have to come back.”

Although he was ten miles from the commotion off Orleans, Lieutenant (JG) Elijah Williams, the executive officer at the Chatham Naval Air Station, identified the sound coming from the sea as shellfire even before Pierce’s message was received. Still, the station had two big problems. First, most of Chatham’s pilots were searching for a missing blimp. Second, many of the pilots who remained on base were rumored to be off playing baseball against the crew of a minesweeper in Provincetown. It was a Sunday morning, after all.

At 10:49 a.m., Lt. Williams managed to secure a Curtiss HS-1L flying boat and a crew to fly it. One minute later, the air station received the delayed alert from U.S. Coast Guard Station Number 40 confirming what he feared all along: a submarine attack!

Moments later, Ensign Eric Lingard and his two-man crew took off from the water runway and soared into the clouds. Flying through the mid-morning haze, Lingard aimed the nose of his plane north, racing as fast as he could to Orleans. If things went as planned, his flying boat would reach the beach in just a few minutes.

By now, Pierce and his surfmen were within earshot of the Perth Amboy’s lifeboat. Worried that the surfmen might stray into the sub’s shellfire, Captain Tapley shouted to Pierce from his lifeboat, “All have left the barges. My crew is here. For Christ’s sake, don’t go out where they are.”

Number One Surfman Moore jumped aboard the Perth Amboy’s lifeboat and began to administer first aid to the wounded sailors, starting with John Bogovich, who by then was a semiconscious, bloody heap in the stern of the boat. Moore dug through his first aid kit and wrapped a tourniquet above Bogovich’s shattered arm to stem the bleeding then began to row furiously for shore with the survivors.

Flying north along Cape Cod’s coast, Lingard and his cohorts were closing in on the U-156. When Lingard got the bulk of his seaplane over the sub, his bombardier at the bow of the plane would release the machine’s sole Mark IV bomb, ideally putting a quick end to the nightmare going on in the ocean below.

The bombardier lined his sight “dead on the deck” and pulled the release just 800 feet above the sub, defying instructions to bomb their target at a safe distance. But the Mark IV bomb failed to drop.

Lingard circled around a second time, flying just 400 feet above the U-boat—so close that the bomb’s explosion below would likely blow the men from their aircraft.

Again, the bomb failed to release. It was stuck. Frustrated but not willing to throw in the towel, the bombardier jumped out of the cockpit and onto the plane’s lower wing before the target below their aircraft was out of range. Lingard watched in disbelief as a blast of wind nearly sent their “fearless” mechanic tumbling into the ocean below. Gripping the plane’s strut with one hand and holding the bomb with the other, the bombardier took a deep breath, uncurled his fingers and released the flying boat’s single Mark IV.

Unfortunately, the bomb was a dud, and failed to explode when it hit the sea.

Having literally dodged a bullet, the U-156 aimed her deck guns at the annoying fly buzzing over her head. At least three bursts of fire flew past the aviators, but none hit the plane. Lingard climbed high into the sky to avoid additional fire and planned to track the submerging sub until the air station sent additional planes—preferably planes with working bombs.

By now, Captain Tapley, Bogovich and other members of the Perth Amboy had reached the beach at Station Number 40. Pierce and his lifesavers arrived on shore around the same time. A local doctor was summoned to help the wounded sailors. Captain Pierce breathed a sigh of relief and then turned his attention back toward the four barges bobbing helplessly out at sea; thankfully those sailors had all launched lifeboats and appeared to be en route to Nauset Beach, two miles to the north.

The Chatham Naval Air Station had suffered a number of setbacks since first receiving word of the submarine attack. It seemed everything that could go wrong, did go wrong.

At 11:04 a.m., the station’s commander, Captain Phillip Eaton, touched down at the air station, having ended his search for the missing blimp, and was briefed on the seemingly unbelievable situation going on offshore. Knowing the station was short on pilots, the commander decided to take matters into his own hands. At 11:15 a.m., he took off in an R-9 seaplane in an effort to personally sink the German raider.

Lingard, who had been tracking and circling the sub—all the while evading fire—greeted the arrival of the captain’s seaplane with renewed vigor. “[It was] the prettiest sight I ever hoped to see,” he said, according to A History of the United States Coast Guard in the World War. “Right through the smoke of the wreck, over the lifeboats and all, here came Captain Eaton’s plane, flying straight for the submarine, and flying low. He saw [the submarine’s] high-angle gun flashing, too, but he came ahead.”

Lingard hoped his commanding officer would succeed where he and his colleagues had failed and deliver a decisive blow to the raider below.

“As I bore down upon the submarine, it fired,” said Eaton, as recorded in the same book, “I zigzagged and dove as it fired again.”

Despite the fire, Eaton was determined to position his plane above the submarine in order to hit his target. Glancing below, he seemed to have arrived just in time.

“They were getting under way and scrambling down the hatch when I flew over them and dropped my bomb,” Eaton recalled, according to a historical record at the National Archives.

At 11:22 a.m., Eaton braced for the explosion. Instead, his payload splashed 100 feet from the sub—another dud. “Had the bomb functioned, the submarine would have literally been smashed,” Eaton lamented in Crisp’s book.

Enraged, Eaton reportedly grabbed a monkey wrench from a toolbox inside his cockpit and hurled it at the Germans. Still not content, Eaton then dumped the rest of the plane’s tools—as well as the metal toolbox—over the side with the hope of at least giving one of the German sailors a concussion. Those on the sub, in turn, thumbed their noses at the paper tiger in the sky.

The raider had lucked out so far, but the crew of the U-156 had no idea that the airplanes circling above were out of bombs. The next payload dropped from the sky could destroy the sub, and other planes might soon be on their way. The Germans decided it was finally time to head back out to sea. At approximately 11:25 a.m., the captain ordered his submarine to dive. Like a magician, she disappeared underneath the surface behind a cloud of smoke.

Captain Eaton breathed a sigh of relief. Although the bombs dropped from the sky had failed to detonate, perhaps his planes had at least hastened the sub’s exit.

Finally, after an hour and a half, the Attack on Orleans was over. During that time, nearly 150 rounds had been fired by the U-156—an average of more than one every minute. Miraculously, no one was killed, and John Bogovich—as well as the other sailors injured that day—would make a full recovery.* The attack was like nothing the inhabitants of Orleans had ever experienced before. Residents were soon bounding down the bluffs, eager to meet the heroic sailors who had beaten, or at least survived, the German onslaught. In the days that followed, the sandy roads that snaked their way to this small coastal hamlet of Orleans were crammed with newsmen eager to make sense of the raid and interview survivors and residents who had witnessed the only attack on American soil during the First World War.

*Editor's Note, July 30, 2018: A previous version of this article wrongly stated that no one was injured in the attack on Orleans, when, in fact, there were injuries but no one was killed.