How to Save the Taj Mahal?

A debate rages over preserving the awe-inspiring, 350-year-old monument that now shows signs of distress from pollution and shoddy repairs

To view the Taj Mahal far from the hawkers and crowds, I had hoped to approach it in a small boat on the Yamuna River, which flows in a wide arc along the rear of the majestic 17th-century tomb.

My guide, a journalist and environmental activist named Brij Khandelwal, was skeptical. The river was low, he said; there may not be enough water to float a boat. But he was game. So one morning, we met in downtown Agra, a city of more than 1.4 million people, near a decaying sandstone arch called the Delhi Gate, and headed for the river, dodging vegetable carts and motorized rickshaws, kids and stray dogs. Sometimes drivers obeyed the traffic signals; other times they zoomed through red lights. We crossed the Jawahar Bridge, which spans the Yamuna, and made our way into a greener area, then took a turn where men and women were selling repaired saris on the side of the road. Eventually we arrived at a spot opposite the Taj. There we hoped to find a fisherman to take us across.

Next to a shrine to Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, a hero of India’s lower castes, the road dips down toward the Yamuna. But only a dry, dusty riverbed was to be seen, cordoned off by a fence and metal gate. We knew the river did flow, however weakly, perhaps 50 yards away. But soldiers manning a nearby post told us it was forbidden to pass any farther. Indian authorities were concerned about Muslim terrorists opposed to the Indian government who had threatened to blow up the Taj—ironic, given that it’s one of the world’s finest examples of Islamic-inspired architecture. We stood before a rusty coil of barbed wire, listening to chanting from the nearby shrine, trying to make out the glory of the Taj Mahal through the haze.

The Indian press has been filled with reports that the latest government efforts to control pollution around the Taj are failing and that the gorgeous white marble is deteriorating—a possible casualty of India’s booming population, rapid economic expansion and lax environmental regulations. Some local preservationists, echoing the concerns of R. Nath, an Indian historian who has written extensively about the Taj, warn that the edifice is in danger of sinking or even collapsing toward the river. They also complain that the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has done slipshod repair work and call for fresh assessments of the structure’s foundations.

The criticisms are a measure of how important the complex is to India and the world, as a symbol of historical and cultural glory, and as an architectural marvel. It was constructed of brick covered with marble and sandstone, with elaborate inlays of precious and semiprecious stones. The designers and builders, in their unerring sense of form and symmetry, infused the entire 42-acre complex of buildings, gates, walls and gardens with unearthly grace. “It combines the great rationality of its design with an appeal to the senses,” says Ebba Koch, author of The Complete Taj Mahal, a careful study of the monument published in 2006. “It was created by fusing so many architectural traditions—Central Asian, Indian, Hindu and Islamic, Persian and European—it has universal appeal and can speak to the whole world.”

Part of the Taj Mahal’s beauty derives from the story the stones embody. Though a tomb for the dead, it is also a monument to love, built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, fifth in a line of rulers who had originally come as conquerors from the Central Asian steppes. The Mughals were the dominant power on the Indian subcontinent for much of the 16th to 18th centuries, and the empire reached its cultural zenith under Shah Jahan. He constructed the Taj (which means “crown,” and is also a form of the Persian word “chosen”) as a final resting place for his favorite wife, Arjumand Banu, better known as Mumtaz Mahal (Chosen One of the Palace). A court poet recorded the emperor’s despair at her death in 1631, at the age of 38, after giving birth to the couple’s 14th child: “The color of youth flew away from his cheeks; The flower of his countenance ceased blooming.” He wept so often “his tearful eyes sought help from spectacles.” To honor his wife, Shah Jahan decided to build a tomb so magnificent that it would be remembered throughout the ages.

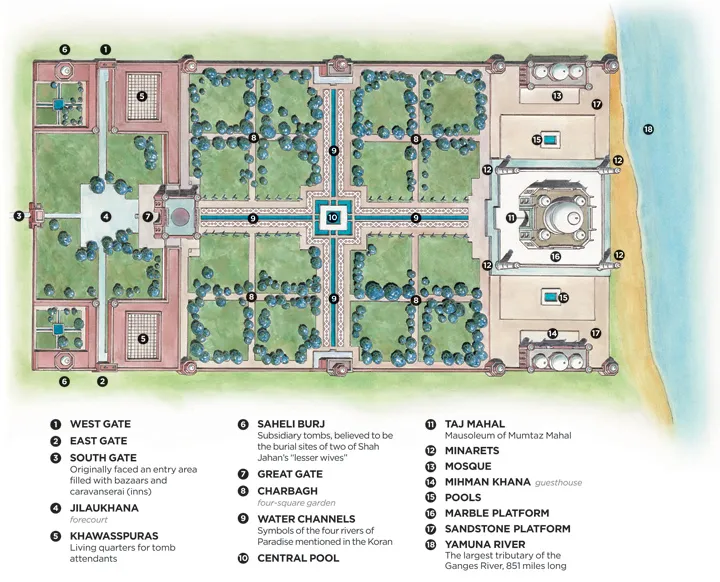

For more than 15 years, he directed the construction of a complex of buildings and gardens that was meant to mirror the Islamic vision of Paradise. First he selected the perfect spot: it had to be tranquil, away from the bustle of Agra, even then a thriving commercial center. “You had many flimsy detached little houses where the locals lived and where, occasionally, sparks would fly out of cooking fires and catch the thatch in the roofs and set whole neighborhoods aflame,” says Diana Preston, author, with her husband, Michael, of Taj Mahal: Passion and Genius at the Heart of the Mughal Empire.

Near the river, where wealthy Mughals were building grand mansions, Shah Jahan acquired land from one of his vassals, the Raja of Amber. He could have simply seized it. But according to Islamic tradition, a woman who dies in childbirth is a martyr; her burial place is holy and must be acquired justly. Shah Jahan provided four properties in exchange.

The Taj site was located along a sharp bend in the Yamuna, which slowed the movement of the water and also reduced the possibility of erosion along the riverbank. The water, moreover, provided a glistening mirror to reflect light from the marble, which changes color and tone depending on the hour, day and season. “Marble is of crystalline composition, allowing light to enter rather deeply before it is reflected,” says Koch. “It responds very strongly to different atmospheric conditions, which gives it a spiritual quality.” Across the river, where we had earlier tried to find a boat, is the Mahtab Bagh (Moonlight Garden). Today the area is a restored botanical garden, but it was once part of the Taj’s overall design, a place to view the mausoleum by the light of the moon and stars.

Shah Jahan employed top architects and builders, as well as thousands of other workers—stone carvers and bricklayers, calligraphers and masters of gemstone inlay. Lapis lazuli came from Afghanistan, jade from China, coral from Arabia and rubies from Sri Lanka. Traders brought turquoise by yak across the mountains from Tibet. (The most precious stones had been looted long ago, says Preston.) Ox-drawn carts trekked roughly 200 miles to Rajasthan where the Makrana quarries were celebrated for their milky white marble (and still are). Laborers constructed scaffolding and used a complex system of ropes and pulleys to haul giant stone slabs to the uppermost reaches of the domes and minarets. The 144-foot-high main dome, constructed of brick masonry covered in white marble, weighs 12,000 tons, according to one estimate. The Taj was also the most ambitious inscription project ever undertaken, depicting more than two dozen quotations from the Koran on the Great Gate, mosque and mausoleum.

I had visited the Taj Mahal as a tourist with my family in 2008, and when I read of renewed concerns about the deterioration of the monument, I wanted to return and take a closer look.

Unable to cross the river by boat, I went to the Taj complex in the conventional manner: on foot, and then in a bicycle rickshaw. Motor vehicles are not allowed within 1,640 feet of the complex without government approval; the ban was imposed to reduce the air pollution at the site. I bought my $16.75 ticket at a government office near the edge of the no-vehicle zone, next to a handicraft village where rickshaw drivers wait for work. Riding in the shade in a cart propelled by a human being exposed to blazing sun felt awkward and exploitative, but environmentalists promote this form of transport as nonpolluting. For their part, rickshaw drivers seem glad for the work.

At the end of the ride, I waited in a ten-minute ticket-holders line at the East Gate, where everyone endures a polite security check. After a guard searched my backpack, I walked with other tourists—mostly Indian—into the Jilaukhana, or forecourt. Here, in the days of Shah Jahan, visitors would dismount from their horses or elephants. Delegations would gather and compose themselves before passing through the Great Gate to the gardens and the mausoleum. Even now, a visitor experiences a spiritual progression from the mundane world of the city to the more spacious and serene area of the forecourt and, finally, through the Great Gate to the heavenly abode of the riverfront gardens and mausoleum.

The Great Gate is covered with red sandstone and marble, and features flowery inlay work. It has an imposing, fortress-like quality—an architectural sentry guarding the more delicate structure within. The enormous entranceway is bordered by Koranic script, a passage from Sura 89, which beckons the charitable and faithful to enter Paradise. Visitors stream through a large room, an irregular octagon with alcoves and side rooms, from where they catch their first view of the white-marble mausoleum and its four soaring minarets nearly 1,000 feet ahead.

The mausoleum sits atop a raised platform in the distance, at the end of a central water channel that bisects the gardens and serves as a reflecting pool. This canal, and another that crosses on an east-west axis, meet at a central reservoir, slightly raised. They are designed to represent the four rivers of Paradise. Once, the canals irrigated the gardens, which were lusher than they are today. Mughal architects constructed an intricate system of aqueducts, storage tanks and underground channels to draw water from the Yamuna River. But now the gardens are watered from tube wells.

To further mimic the beauty of Paradise, Shah Jahan planted flowers and fruit trees, which encouraged butterflies to flit about. Some historians say the trees were grown in earth that was originally below the pathways—perhaps as much as five feet down, allowing visitors to pluck fruit as they strolled the grounds. By the time Britain assumed rule over Agra in 1803, the Taj complex was dilapidated and the gardens were overgrown. The British cut down many of the trees and changed the landscaping to resemble the bare lawns of an English manor. Visitors today often sit on the grass.

The domed mausoleum appears as wondrous as a fairy tale palace. The only visual backdrop is the sky. “The Taj Mahal has a quality of floating, an ethereal, dream-like quality,” says Preston. The bustling crowds and clicking cameras can detract from the serenity, but they also fill the complex with vitality and color. Walking around the back of the mausoleum, I stooped to take a photo of some rhesus monkeys. One jumped on my back before quickly bounding off.

The Taj Mahal is flanked on the west by a mosque, and on the east by the Mihman Khana, which was originally used as a guesthouse, and later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, as a banquet hall for British and Indian dignitaries. I found it a lovely place to escape the sun. A small boy in a black leather jacket claiming to be the son of a watchman at the Taj offered to take my picture standing under a large arched doorway, with the marble mausoleum in the background. I gave him my camera and he told me where to stand, changing the settings on my Canon and firing off photos like a pro. After that, he led me down some steps to a corner of the gardens shaded by trees to take what he called the “jungle shot,” with branches in the foreground and the white marble of the mausoleum behind. We found a chunk of carved stone, perhaps a discarded piece used in restoration work or a stone detached from the monument itself. (Three years ago, a seven-foot slab of red sandstone fell off the East gate.) Two soldiers approached, scolded the boy and shooed him away.

The first day I toured the complex, several hundred people were waiting in line to enter the mausoleum; I returned later in the week when the line was much shorter. Inside the main room, the richly engraved cenotaphs (empty memorial sarcophagi) of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan are located behind an elaborate jali, or marble screen. A second set of cenotaphs is located in a lower chamber, inaccessible to ordinary visitors. It is believed the emperor and his beloved wife are buried even more deeply in the earth. The cenotaphs, the marble screen and marble walls are decorated with exquisite floral patterns of colored stone and inlaid inscriptions from the Koran.

While the Taj is a testament to love, it also embodied the power of Shah Jahan himself. As the emperor’s historian wrote: “They laid the plan for a magnificent building and a dome of high foundation which for its loftiness will until the Day of Resurrection remain a memorial to the sky-reaching ambition of His Majesty...and its strength will represent the firmness of the intentions of its builder.”

Presumably, the end of time is still a long way off, but the Taj is slowly deteriorating now. Seen up close, the marble has yellow-orange stains in many places; some slabs have small holes where the stone has been eaten away; in a few places, chunks have fallen from the facade; my guide Brij and I even found a bit of recent graffiti on the white marble platform, where two visitors, Ramesh and Bittoo, had signed their names in red ink.

The sandstone of the terraces and walkways is particularly weathered. Where restoration work has been done, it sometimes appears sloppy. Workers have filled holes with a cement-like substance of a mismatched color. In at least one instance, it appears that someone stepped in the wet glop before it dried, leaving an indent the size and shape of a small shoe. The grouting in some of the gaps between marble slabs of the walls looks like the amateur work I’ve done in my bathroom.

For decades activists and lawyers have been waging a legal battle to save the Taj Mahal from what they believe is environmental degradation. M.C. Mehta, currently one of India’s best-known lawyers, has been at the forefront of that fight. I met him twice in New Delhi in a half-finished office with holes in the walls and wires dangling out.

“The monument gives glory to the city, and the city gives glory to the monument,” he tells me, exasperated that more has not been done to clean up Agra and the Yamuna River. “This has taken more than 25 years of my life. I say: ‘Don’t be so slow! If somebody is dying, you don’t wait.’”

When he began his campaign in the 1980s, one of Mehta’s main targets was an oil refinery upwind of the Taj Mahal that spewed sulfur dioxide. Preservationists believed the plant emissions were causing acid rain, which was eating away at the stone of the monument—what Mehta calls “marble cancer.” Mehta petitioned the Supreme Court and argued that the Taj was important both to India’s heritage and as a tourist attraction that contributed more to the economy than an oil refinery. He wanted all polluters, including iron foundries and other small industries in Agra, shut down, moved out or forced to install cleaner technology. In 1996, twelve years after he filed the motion, the court ruled in his favor, and the foundries around Agra were closed, relocated or—as was the case with the refinery—compelled to switch to natural gas.

But for all his successes, Mehta believes there’s much more to be done. Traffic has surged, with more than 800,000 registered vehicles in the city. Government data shows that particulate matter in the air—dust, vehicle exhaust and other suspended particles—is well above prescribed standards. And the Yamuna River arrives in Agra bearing raw sewage from cities upstream.

The river, once such an integral component of the Taj’s beauty, is a mess, to put it mildly. I visited one of the city’s storm drains where it empties at a spot between the Taj Mahal and the Agra Fort, a vast sandstone-and-marble complex that was once home to Mughal rulers. In addition to the untreated human waste deposited there, the drain belches mounds of litter—heaps of plastic bags, plastic foam, snack wrappers, bottles and empty foil packets that once held herbal mouth freshener. Environmental activists have argued that such garbage dumps produce methane gas that contributes to the yellowing of the Taj’s marble.

When I stepped down to photograph the trash heap, I felt an unnatural sponginess underfoot—the remains of a dead cow. According to Brij, who has reported on the subject for Indian publications, the bodies of children have also been interred here by people too poor to afford even a rudimentary funeral. The dump and ad hoc cemetery within view of the splendor of the Taj is a jarring reminder of the pressures and challenges of modern India. The state of Uttar Pradesh, where Agra is located, had plans in 2003 to develop this area for tourists. The project was called the Taj Corridor. Originally conceived as a nature walk, it was transformed secretly into plans for a shopping mall. The whole project crashed soon after it began amid allegations of wrongdoing and corruption. Sandstone rubble remains strewn across the dump site.

R.K. Dixit, the Asi’s senior official at the Taj, has an office inside the edifice of the Great Gate. He sits under a white domed roof, with a swirling symbol of the sun at its apex. The room has one window, shaded by a honeycomb screen of red sandstone, which offers a direct view of the mausoleum.

I ask him about the Taj’s deterioration. He acknowledges the sad state of the river. But while he agrees that some of the marble is yellowing, he says that’s only natural. The ASI has been taking steps to clean it. Restorers first used chemical agents, including an ammonia solution.They now use a type of sedimentary clay called fuller’s earth. “It takes the dust and dirt from the pores of the marble, and after removing the impurities, [the fuller’s earth] falls down,” says Dixit. Some critics have derided this “spa treatment,” saying that fuller’s earth is a bleaching agent and will ultimately do more harm than good. But it’s used elsewhere, and when I later contact international conservationists to get their opinion, they tell me it’s unlikely to do damage.

There are many in Agra who believe that all the worries about the Taj are exaggerated—that far too much attention is paid to the monument at the expense of other priorities. They say the restrictions imposed upon the city’s several hundred brick kilns, iron foundries and glassworks to reduce air pollution have harmed the local economy. S.M. Khandelwal, a business leader in Agra who opposed Mehta’s legal campaign, has long argued that such businesses were responsible for only a tiny fraction of the fumes emitted in the city, and that the more significant polluters were vehicles and power generators. “I was very angry that everyone was so concerned about the Taj Mahal and not about the [livelihoods of the] people of Agra,” he says.

Even some international experts doubt that air pollution is the prime cause of the discoloring and pitting of the monument’s marble. At least some of the yellow marks on the monument, for instance, are rust stains from iron fixtures that hold the marble slabs in place. Marisa Laurenzi Tabasso, an Italian chemist and conservation scientist, has studied the Taj Mahal on behalf of international organizations and Indian authorities. “Most of the problems with the marble are not from pollution, but from climatic conditions,” she says. These include heat, sunlight and also moisture, which promotes the growth of algae, leading to biological decay of the stone. Laurenzi Tabasso says the main human impact on the monument probably occurs inside the tomb, where the moist breath of thousands of daily visitors—and their oily hands rubbing the walls—has discolored the marble.

And the number of visitors is growing. Rajiv Tiwari, president of the Federation of Travel Associations in Agra, tells me that between March 2010 and March 2011, the number of people touring sites in the city jumped from an estimated 3.8 million to nearly five million.

The main concern, however, is the Yamuna River. Some of the activists I met in Agra cited arguments made by R. Nath, who has written dozens of books on Mughal history and architecture. Nath believes that the river water is essential to maintaining the monument’s massive foundation, which is built on a complex system of wells, arches—and, according to Nath—spoked wheels made of sal wood. Nath and some activists worry the groundwater levels beneath the monument are falling—partly the result of a barrier that was constructed upstream to augment public water supplies—and they fear the wood may disintegrate if it isn’t kept moist. Nath also believes the Yamuna River itself is part of a complicated engineering feat that provides thrust from different angles as the water wends its way behind the mausoleum. But, due to the lower water level, the Yamuna now dries up for months at a time. Without that stabilizing counterforce of flowing water, the Taj “has a natural tendency to slide or sink into the river,” Nath says.

A detailed survey of the Taj was carried out in the 1940s during British rule in India, showing that the marble platform beneath the mausoleum was more than an inch lower on the northern side, near the river, than on the south. Cracks were apparent in the structure, and minarets were slightly out of plumb. The implication of the study is disputed: some maintain that the monument was always a tad askew, and perhaps the minarets were tilted slightly to make sure they never fell onto the mausoleum. Nath argues that the Mughals were perfectionists, and that a slow shifting has taken place. A 1987 study by the Rome-based International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property concluded there was no evidence of structural distress or foundation failure, but said there was “remarkably little information about the foundations and the nature of the subsoil.” The report advised it would be “prudent to make a full geotechnical survey” and “highly advisable” to drill several deep boreholes to examine beneath the complex. A Unesco report in 2002 praised the upkeep of the monument, but repeated that a geotechnical survey “would be justified.”

When I asked ASI officials about the foundation, they said it was fine. “Geotechnical and structural investigations have been conducted by the Central Building Research Institute,” ASI director Gautam Sengupta told me in an e-mail. “It has been found...that [the] foundation and superstructure of [the] Taj Mahal are stable.” ASI officials, however, declined to answer several queries about whether deep boreholes had been drilled.

When Mehta visits the city these days, he keeps a low profile. He has several new petitions for action before the Supreme Court—in particular, he wants the government to restore and protect the Yamuna River and ensure that new construction in Agra is in harmony with the style and feel of old India. He shrugs off the anger directed at him, taking it as a sign of success. “I have so many people who consider me their enemy,” he says. “But I have no enemies. I’m not against anybody.”

What would Shah Jahan make of it all? Dixit believes he would be saddened by the state of the river, “but he’d also be happy to see the crowds.” Shah Jahan might even be philosophical about the slow deterioration. He had designed the monument to endure beyond the end of the world, yet the first report on record of damage and leaks came in 1652. The emperor was certainly familiar with the impermanence of things. When his beloved Mumtaz Mahal died, a court historian wrote:

“Alas! This transitory world is unstable, and the rose of its comfort is embedded in a field of thorns. In the dustbin of the world, no breeze blows which does not raise the dust of anguish; and in the assembly of the world, no one happily occupies a seat who does not vacate it full of sorrow.”

If the symbolic power of the Taj can be harnessed to fight for a cleaner river, cleaner air and better living conditions, all the better. But most of the Taj Mahal’s flaws don’t detract from the overall effect of the monument. In some ways, the yellowing and pocking add to its beauty, just as flaws in a handmade Oriental carpet enhance its aesthetic power, or the patina on an antique piece of furniture is more valued, even with its scratches and scars, than a gleaming restoration job. Standing before the Taj Mahal, it’s comforting to know that it is not, in fact, of another world. It is very much part of this ephemeral, unpredictable one we inhabit—a singular masterpiece that will likely be around for many years or even lifetimes to come, but which, despite our best efforts, cannot last forever.

Jeffrey Bartholet is a freelance writer and foreign correspondent. Photojournalist Alex Masi is based in Mumbai.