How Winston Churchill Endured the Blitz—and Taught the People of England to Do the Same

In a new book, best-selling author Erik Larson examines the determination of the ‘British Bulldog’ during England’s darkest hour

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/2f/642fe98e-a0a7-4506-9379-68d81356a1d5/winston_churchill_visits_bomb_damaged_cities-main.jpg)

For 57 consecutive nights in 1940, Nazi Germany tried to bring England to its knees. Waves of planes pummeled cities with high-explosive bombs and incendiary devices as part of a campaign to break the English spirit and destroy the country’s capacity to make war. One man stood strong against the onslaught: Winston Churchill.

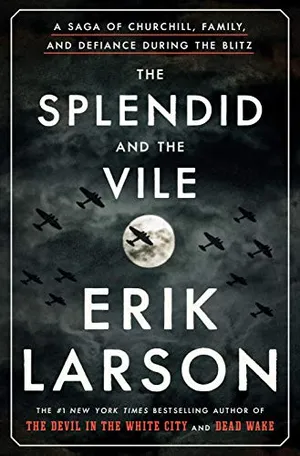

Historian Erik Larson’s new book takes an in-depth look at this defiant prime minister who almost singlehandedly willed his nation to resist. The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz examines a leader in crisis—a challenge of epic proportions with the fate of democracy hanging in the balance. Larson, author of the New York Times best sellers The Devil in the White City and Dead Wake, details Churchill’s boldness in standing alone against the Nazi menace by urging his countrymen to overcome hopelessness and fight back. He combed archives with a new lens to uncover fresh material about how England’s “bulldog” rallied his nation from imminent defeat to stand bloodied but unbowed as an island fortress of freedom. In an interview with Smithsonian, Larson describes how he came to write his new book and what surprises he learned about the man who reminds us today what true leadership is all about.

Why did you write this book? Any why now?

That’s a question with a lot of things to unpack. My wife and I had been living in Seattle. We have three grown daughters who had all flown the coop. One thing led to another and we decided that we were going to move to Manhattan, where I’d always wanted to live. When we arrived in New York, I had this epiphany—and I’m not exaggerating. It really was a kind of epiphany about what the experience of 9/11 must have been like for residents of New York City. Even though I watched the whole thing unfold in real-time on CNN and was horrified, when I got to New York I realized this was an order-of-magnitude traumatic event. Not just because everything was live and right in front of your face; this was an attack on your home city.

Feeling that very keenly, I started thinking about the German air campaign against London and England. What was that like for them? It turned out to have been 57 consecutive nights of bombings—57 consecutive 9/11s, if you will. How does anybody cope with that? Then, of course, there was six more months of raids at intervals and with increasing severity. How does the average person endure that, let alone the head of the country, Winston Churchill, who’s also trying to direct a war? And I started thinking how do you do something like that? What’s the intimate, inside story?

Remember, Churchill—this was one thing that really resonated with me as a father with three daughters—was not just the leader of Great Britain and a London citizen, but he was a father. He had a young daughter who was only 17. His family was spread out throughout London. How do you cope with that anxiety on a daily level? Every night, hundreds of German bombers are flying over with high-explosive bombs.

So why now? I think the timing is good because we all could use a refresher course on what actual leadership is like.

The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz

In The Splendid and the Vile, Erik Larson shows, in cinematic detail, how Churchill taught the British people “the art of being fearless.” Drawing on diaries, original archival documents, and once-secret intelligence reports—some released only recently—Larson provides a new lens on London’s darkest year through the day-to-day experience of Churchill and his family.

Churchill writes in his memoir that he’s ecstatic over the opportunity to lead the country at such a difficult time. Anybody else would be cringing. Where did his confidence come from?

In his personal memoir on the history of the war, he exalts that he became prime minister. The world is going to hell, but he is just thrilled. That’s what really sets him apart from other leaders. Not only was he undaunted, he was actively, aggressively thrilled by the prospect of this war.

Lord Halifax, who was considered by many to be the rightful successor to [prime minister Neville] Chamberlain, didn’t want the job. He had no confidence he could negotiate a war as prime minister. But Churchill had absolute confidence. Where did that come from? I don’t know. I’ve read a lot about his past in doing research and I’ve thought a lot about it. I still don’t have a good answer.

What surprised you the most about Churchill?

A lot of things surprised me. What surprised me the most was simply that Churchill really could be quite funny. He knew how to have fun. One scene in particular will stay with me, even as I go on to other books. One night he was at the prime ministerial country estate, Chequers, wearing this blue one-piece jumpsuit he designed and his silk flaming-red dressing gown, carrying a Mannlicher rifle with a bayonet. He’s doing bayonet drills to the strains of martial music from the gramophone. That’s the kind of guy he was. He was said to be absolutely without vanity.

How did you go about your research for this book?

So much has been done on Churchill. And if you set out to read everything, it would take a decade. My strategy from the beginning was to read the canon of Churchill scholarship to the point where I felt I had a grasp of everything that was going on. Then, rather than spend the next ten years reading additional material, I was going to do what frankly I think I do best: dive into the archives.

I scoured various archives in hopes of finding fresh material using essentially a new lens. How did he go about day to day enduring this onslaught from Germany in that first year as prime minister? From that perspective, I came across a lot of material that was perhaps overlooked by other scholars. That’s how I guided myself throughout the book. I was going to rely on the archives and firsthand documents to the extent that I could to build my own personal Churchill, if you will. And then, once I had accumulated a critical mass of materials, I moved on to start writing the book.

My main source was the National Archives of the U.K. at Kew Gardens, which was fantastic. I probably have 10,000 pages of material from documents. I also used the Library of Congress in the U.S. The manuscript division reading room has the papers of Averell Harriman, who was a special envoy for FDR. It has also the papers of Pamela Churchill, wife the prime minister’s son, Randolph, who later married Harriman. And even more compelling are the papers of Harriman’s personal secretary Robert Meiklejohn, who left a very detailed diary. There is a lot of other material describing the Harriman mission to London, which was all-important in spring of 1941.

Numerous accounts detail how Churchill liked to work in the nude or in the tub. How did that tie into your overall view of Churchill?

He did that a lot. And he was not at all shy about it. There’s a scene that John Colville [private secretary to Churchill] describes in his diary. Churchill was in the bath and numerous important telephone calls were coming in. Churchill would just get out of the bath, take the call, then get back in the bath. It didn’t matter. He did have a complete and utter lack of vanity.

That was one of the aspects of his character that really did help him. He didn’t care. As always, though, with Churchill, you also have to add a caveat. One of the things I discovered was while he had no sense of vanity and didn’t really care what people thought of him, he hated criticism.

What fresh material did you find for the book?

The foremost example is the fact that I was thankfully given permission to read and use Mary Churchill’s diary. I was the second person to be allowed to look at it. I thank Emma Soames, Mary’s daughter, for giving me permission. Mary makes the book because she was Churchill’s youngest daughter at 17 [during the Blitz]. She kept a daily diary that is absolutely charming. She was a smart young woman. She could write well and knew how to tell a story. And she was observant and introspective. There’s also the Meiklejohn diary. A lot of the Harriman stuff is new and fresh. There are materials that I haven’t seen anywhere else.

Another example: Advisors around Churchill were really concerned about how Hitler might be going after the prime minister. Not just in Whitehall, but also at Chequers. It’s kind of surprising to me that the Luftwaffe [the Nazi air force] hadn’t found Chequers and bombed it. Here was this country home with a long drive covered with pale stone. At night, under a full moon, it luminesced like an arrow pointing to the place.

What precautions did Churchill take to stay out of harm’s way during dangerous situations?

He didn’t take many. There are a lot of cases when an air raid was about to occur and Churchill would go to the roof and watch. This was how he was. He was not going to cower in a shelter during a raid. He wanted to see it. By day, he carried on as if there were no nightly air raids. This was part of his style, part of how he encouraged and emboldened the nation. If Churchill’s doing this, if he’s courageous enough, maybe we really don’t have so much to fear.

Churchill would walk through the bombed sections of London following a raid.

He did it often. He would visit a city that had been bombed, and the people would flock to him. There is no question in my mind that these visits were absolutely important to helping Britain weather this period. He was often filmed for newsreels, and it was reported by newspapers and radio. This was leadership by demonstration. He showed the world that he cared and he was fearless.

Did Churchill and the people of Great Britain believe that the bombing would lead to an invasion?

That’s another thing that did surprise me: the extent to which the threat of invasion was seen to be not just inevitable, but imminent. Within days. There was talk of, “Oh, invasion Saturday.” Can you imagine that? It’s one thing to endure 57 nights of bombing, but it’s another to live with the constant anxiety that it is a preamble to invasion.

Churchill was very clear-eyed about the threat from Germany. To him, the only way to really defeat any effort by Hitler to invade England was by increasing fighter strength so the Luftwaffe could never achieve air superiority. Churchill felt that if the Luftwaffe could be staved off, an invasion would be impossible. And I think he was correct in that.

England survives the German bombings. What was the feeling like after the Blitz?

The day after was this amazing quiet. People couldn’t believe it. The weather was good, the nights were clear. What was going on? And day after day, it was quiet. No more bombers over London. That was the end of the first and most important phase of the German air war against Britain. It was the first real victory of the war for England.

When we talk about the Blitz, it’s important to realize the extent to which Churchill counted on America as the vehicle for ultimate victory. He was confident Britain could hold off Germany, but he believed victory would only come with the full-scale participation of the United States. Churchill acknowledged that early on when he met with his son, Randolph, who asked him, “How can you possibly expect to win?” Churchill says, “I shall drag the United States in.” A big part of the story I tell is about also how he went about doing that.

Your book covers that very crucial time in 1940 and 1941. In the epilogue, you jump ahead to July 1945 when the Conservative Party is voted out of office and Churchill is no longer prime minister.

What a shocking reversal! I was so moved when I learned how the family gathered at Chequers for the last time. Mary Churchill was saddened by what was happening. They tried to cheer him up. Nothing worked at first, but then gradually he began to come out of it. And I think at that point he was coming around to accepting this was the reality. But it was hard for him. I think what really hurt him was the idea that suddenly he had no meaningful work to do. That just about crushed him.

What did you learn in writing this book?

Writing about Churchill, dwelling in that world, was really a lovely place for me. It took me out of the present. This may sound like a cliché, but it took me back to a time when leadership really mattered. And truth mattered. And rhetoric mattered.

I love that Churchillians seem to like this book and actually see new things in it. But this book is really for my audience. I’m hoping they are drawn to the story and will sink into this past period as if they were there. I think that’s very important in understanding history.

Churchill was a unifier. He was a man who brought a nation together. As he said, he didn't make people brave, he allowed their courage to come forward. It’s a very interesting distinction. To me, as I say in the book, he taught the nation the art of being fearless. And I do think fearlessness can be a learned art.

Erik Larson will be discussing his book, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, at a Smithsonian Associates event on March 16, 2020.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)