How Woodrow Wilson’s Propaganda Machine Changed American Journalism

The media are still feeling the impact of an executive order signed in 1917 that created ‘the nation’s first ministry of information’

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/9e/8a9ee144-ffc6-4e1e-9f4e-b35fba9452ff/file-20170426-2834-otz8fi.jpg)

When the United States declared war on Germany 100 years ago, the impact on the news business was swift and dramatic.

In its crusade to “make the world safe for democracy,” the Wilson administration took immediate steps at home to curtail one of the pillars of democracy – press freedom – by implementing a plan to control, manipulate and censor all news coverage, on a scale never seen in U.S. history.

Following the lead of the Germans and British, Wilson elevated propaganda and censorship to strategic elements of all-out war. Even before the U.S. entered the war, Wilson had expressed the expectation that his fellow Americans would show what he considered “loyalty.”

Immediately upon entering the war, the Wilson administration brought the most modern management techniques to bear in the area of government-press relations. Wilson started one of the earliest uses of government propaganda. He waged a campaign of intimidation and outright suppression against those ethnic and socialist papers that continued to oppose the war. Taken together, these wartime measures added up to an unprecedented assault on press freedom.

I study the history of American journalism, but before I started researching this episode, I had thought that the government’s efforts to control the press began with President Roosevelt during WWII. What I discovered is that Wilson was the pioneer of a system that persists to this day.

All Americans have a stake in getting the truth in wartime. A warning from the WWI era, widely attributed to Sen. Hiram Johnson, puts the issue starkly: “The first casualty when war comes is truth.”

Mobilizing for war

Within a week of Congress declaring war, on April 13, 1917, Wilson issued an executive order creating a new federal agency that would put the government in the business of actively shaping press coverage.

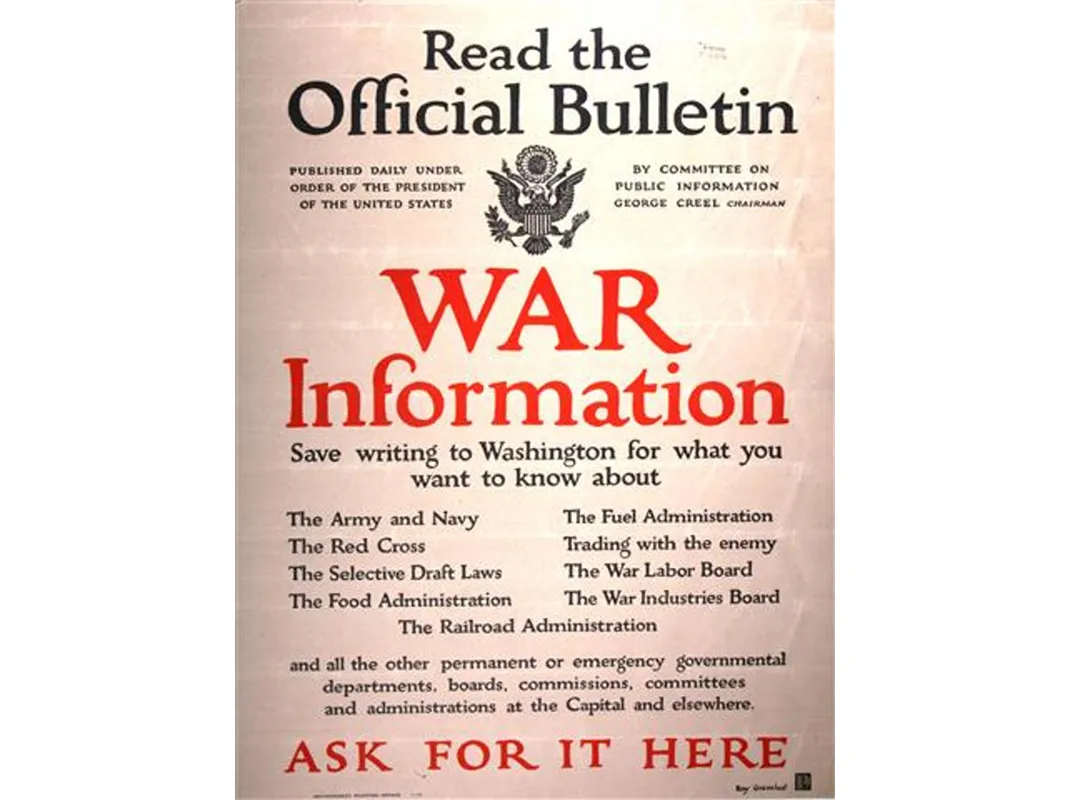

That agency was the Committee on Public Information, which would take on the task of explaining to millions of young men being drafted into military service – and to the millions of other Americans who had so recently supported neutrality – why they should now support war.

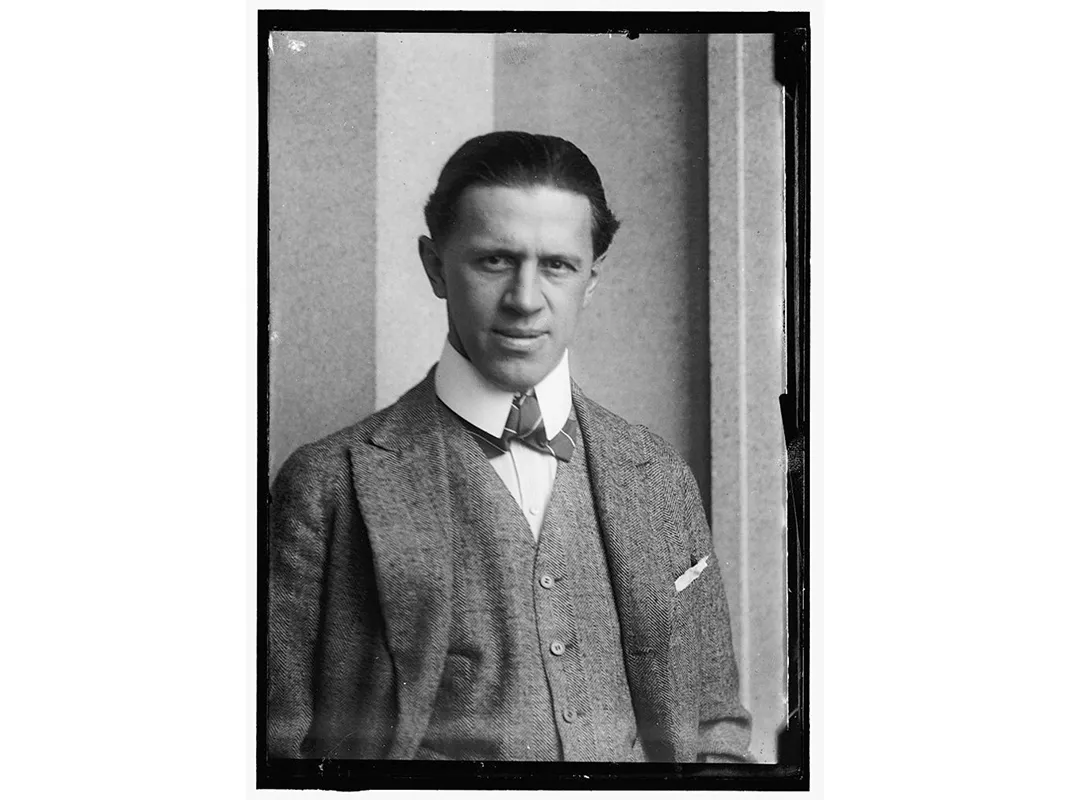

The new agency – which journalist Stephen Ponder called “the nation’s first ministry of information” – was usually referred to as the Creel Committee for its chairman, George Creel, who had been a journalist before the war. From the start, the CPI was “a veritable magnet” for political progressives of all stripes – intellectuals, muckrakers, even some socialists – all sharing a sense of the threat to democracy posed by German militarism. Idealistic journalists like S.S. McClure and Ida Tarbell signed on, joining others who shared their belief in Wilson’s crusade to make the world safe for democracy.

At the time, most Americans got their news through newspapers, which were flourishing in the years just before the rise of radio and the invention of the weekly news magazine. In New York City, according to my research, nearly two dozen papers were published every day – in English alone – while dozens of weeklies served ethnic audiences.

Starting from scratch, Creel organized the CPI into several divisions using the full array of communications.

The Speaking Division recruited 75,000 specialists who became known as “Four-Minute Men” for their ability to lay out Wilson’s war aims in short speeches.

The Film Division produced newsreels intended to rally support by showing images in movie theaters that emphasized the heroism of the Allies and the barbarism of the Germans.

The Foreign Language Newspaper Division kept an eye on the hundreds of weekly and daily U.S. newspapers published in languages other than English.

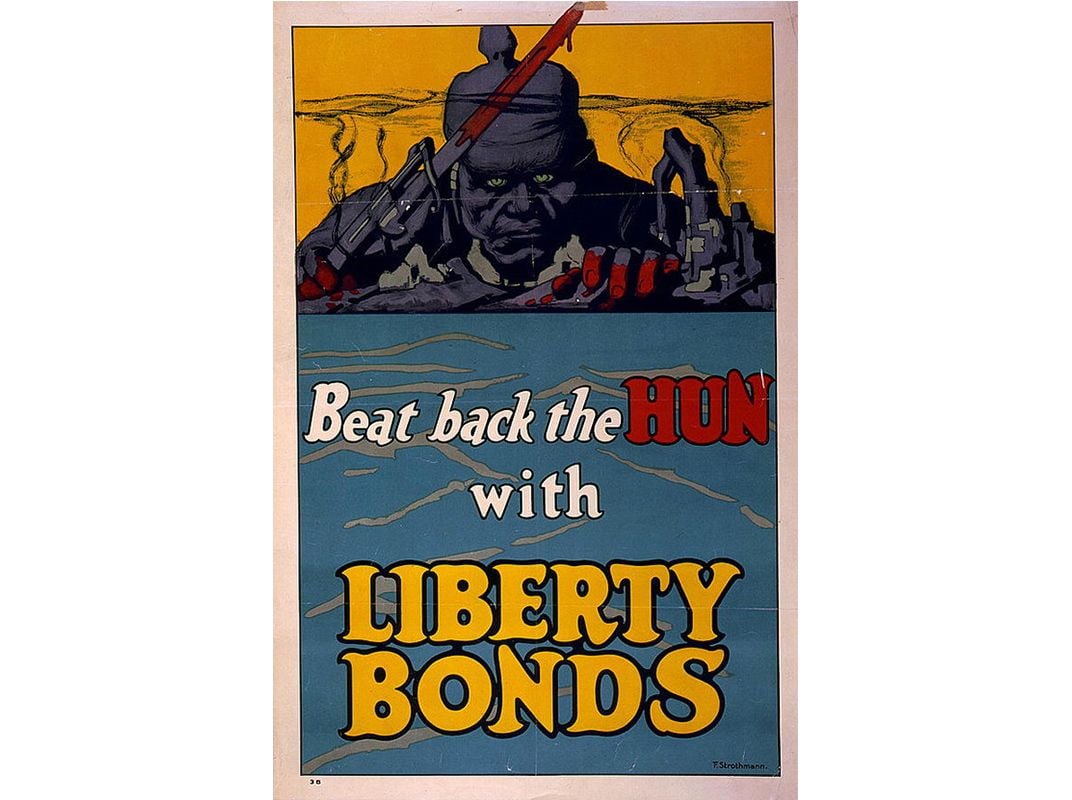

Another CPI unit secured free advertising space in American publications to promote campaigns aimed at selling war bonds, recruiting new soldiers, stimulating patriotism and reinforcing the message that the nation was involved in a great crusade against a bloodthirsty, antidemocratic enemy.

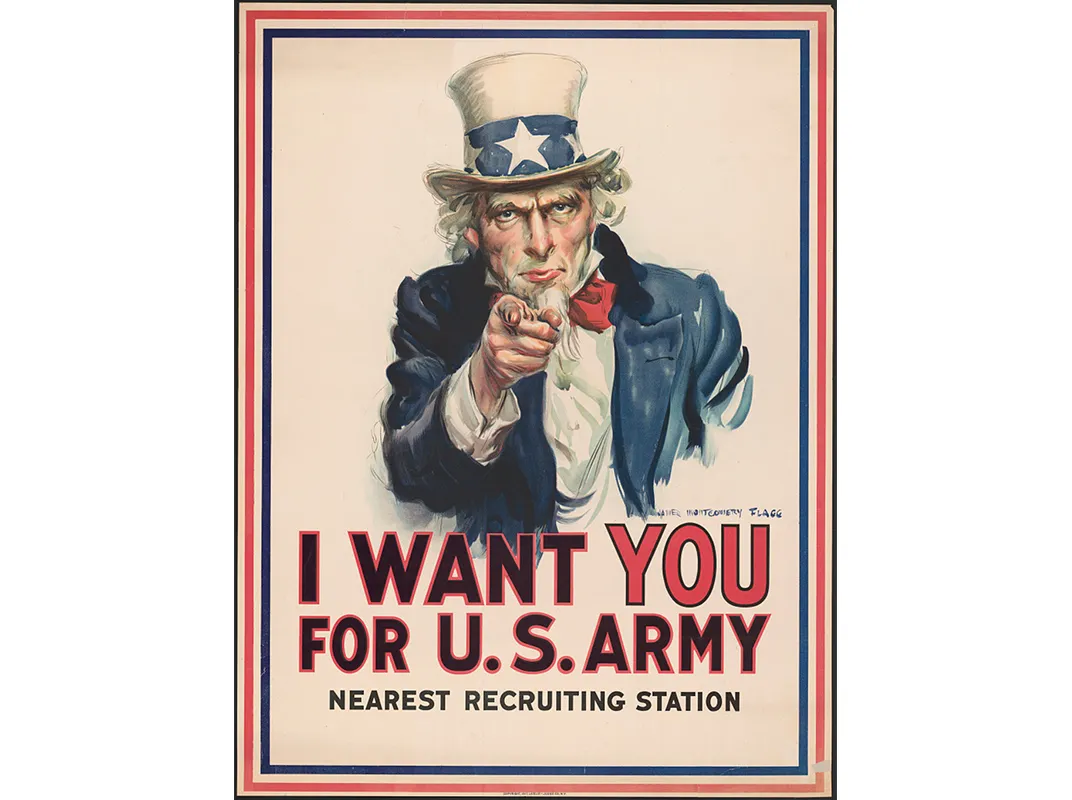

Some of the advertising showed off the work of another CPI unit. The Division of Pictorial Publicity was led by a group of volunteer artists and illustrators. Their output included some of the most enduring images of this period, including the portrait by James Montgomery Flagg of a vigorous Uncle Sam, declaring, “I WANT YOU FOR THE U.S. ARMY!”

**********

Other ads showed cruel “Huns” with blood dripping from their pointed teeth, hinting that Germans were guilty of bestial attacks on defenseless women and children. “Such a civilization is not fit to live,” one ad concluded.

Creel denied that his committee’s work amounted to propaganda, but he acknowledged that he was engaged in a battle of perceptions. “The war was not fought in France alone,” he wrote in 1920, after it was all over, describing the CPI as “a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s greatest adventure in advertising.”

Buried in paper

For most journalists, the bulk of their contact with the CPI was through its News Division, which became a veritable engine of propaganda on a par with similar government operations in Germany and England but of a sort previously unknown in the United States.

In the brief year and a half of its existence, the CPI’s News Division set out to shape the coverage of the war in U.S. newspapers and magazines. One technique was to bury journalists in paper, creating and distributing some 6,000 press releases – or, on average, handing out more than 10 a day.

The whole operation took advantage of a fact of journalistic life. In times of war, readers hunger for news and newspapers attempt to meet that demand. But at the same time, the government was taking other steps to restrict reporters’ access to soldiers, generals, munitions-makers and others involved in the struggle. So, after stimulating the demand for news while artificially restraining the supply, the government stepped into the resulting vacuum and provided a vast number of official stories that looked like news.

Most editors found the supply irresistible. These government-written offerings appeared in at least 20,000 newspaper columns each week, by one estimate, at a cost to taxpayers of only US$76,000.

In addition, the CPI issued a set of voluntary “guidelines” for U.S. newspapers, to help those patriotic editors who wanted to support the war effort (with the implication that those editors who did not follow the guidelines were less patriotic than those who did).

The CPI News Division then went a step further, creating something new in the American experience: a daily newspaper published by the government itself. Unlike the “partisan press” of the 19th century, the Wilson-era Official Bulletin was entirely a governmental publication, sent out each day and posted in every military installation and post office as well as in many other government offices. In some respects, it is the closest the United States has come to a paper like the Soviet Union’s Pravda or China’s People’s Daily.

The CPI was, in short, a vast effort in propaganda. The committee built upon the pioneering efforts of public relations man Ivy Lee and others, developing the young field of public relations to new heights. The CPI hired a sizable fraction of all the Americans who had any experience in this new field, and it trained many more.

One of the young recruits was Edward L. Bernays, a nephew of Sigmund Freud and a pioneer in theorizing about human thoughts and emotions. Bernays volunteered for the CPI and threw himself into the work. His outlook – a mixture of idealism about the cause of spreading democracy and cynicism about the methods involved – was typical of many at the agency.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society,” Bernays wrote a few years after the war. “Propaganda is the executive arm of the invisible government.”

All in all, the CPI proved quite effective in using advertising and PR to instill nationalistic feelings in Americans. Indeed, many veterans of the CPI’s campaign of persuasion went into careers in advertising during the 1920s.

The full bundle of techniques pioneered by Wilson during the Great War were updated and used by later presidents when they sent U.S. forces into battle.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Christopher B. Daly, Professor of Journalism, Boston University