How World War II Helped Forge the Modern FBI

Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, J. Edgar Hoover consolidated immense power—and created the beginnings of the surveillance state

:focal(1837x1417:1838x1418)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e4/1c/e41cb036-239e-434b-a00e-753da8a826fe/gettyimages-514700158.jpg)

If the invasion of Poland in September 1939 produced a shiver of fear in the United States, the invasion of France in the spring of 1940 instilled a lasting sense of dread. During a few days in early May, the Nazi army blitzed into Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland and finally France, where the fabled French Army crumpled at the Maginot Line. On June 14, 1940, Adolf Hitler’s troops marched triumphantly into Paris, unfurling a swastika over the Arc de Triomphe.

“As the 41st week of the war came to a close,” an American reporter wrote back to Washington, “the mighty German army appeared to be writing … an obituary for the France of liberté, égalité, et fraternité.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/a6/b6a6cc8f-1a69-4b37-97fa-8659e1dcd2cb/screenshot_2022-11-17_at_34925_pm.png)

“France’s only hope was the United States,” he added, reciting pleas from Parisians for the U.S. to save them from Nazi terror. But according to pollster George Gallup, a majority of Americans still felt that the war was a European problem, and that rushing to the aid of France would involve American boys in a pointless debacle like World War I.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not try to convince them otherwise, at least not directly. Instead, he urged the nation to improve its defenses and reinitiated a national draft in case war should arrive on American shores. In an address to Congress on May 16, 1940, he urged Americans to ramp up war production, especially of airplanes, tanks and other heavy equipment. Finally, he called for renewed effort against a “fifth column” of spies and saboteurs allegedly hidden throughout the Western Hemisphere, ready to rise up at Hitler’s signal. “We have seen the treacherous use of the ‘fifth column’ by which persons supposed to be peaceful visitors were actually a part of an enemy unit of occupation,” Roosevelt warned Congress, requesting almost a billion dollars in defense funding. In a fireside chat ten days later, he spoke again of “the Trojan horse” and “the fifth column that betrays a nation unprepared for treachery”: enemy saboteurs, spies and sympathizers lying in wait. As in 1939, he counseled Americans to avoid vigilante action, but there was no mistaking the overall message: The Trojan horse was real, it had already passed through America’s gates and it was up to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), above all other agencies, to stop it.

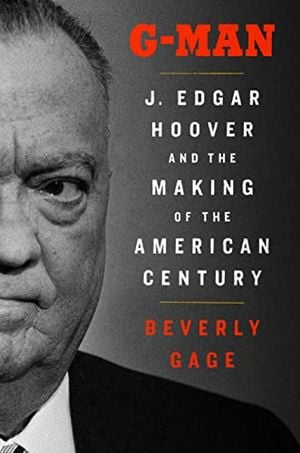

G-Man (Pulitzer Prize Winner): J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century

A major new biography of J Edgar Hoover that draws from never-before-seen sources to create a groundbreaking portrait of a colossus who dominated half a century of American history and planted the seeds for much of today's conservative political landscape.

This rush of concern over homegrown conspiracies and Nazi plots offered an opportunity to the agency’s head, J. Edgar Hoover. During the relative lull of late 1939 and early 1940, Roosevelt had been willing to allow the liberals in his party—even his Republican critics—to wring their hands about civil liberties and attack Hoover’s wartime surveillance plans. With the invasion of France, the president lost patience with those critics and once again committed himself firmly on Hoover’s side. “The president had a tendency to think in terms of right and wrong, instead of terms of legal and illegal,” Attorney General Robert H. Jackson recalled. “Because he thought that his motives were always good for the things that he wanted to do, he found difficulty in thinking there could be legal limitations on them.”

The result was the single swiftest accumulation of power in Hoover’s career. In late May 1940, Roosevelt secretly rejected the Supreme Court’s ban on wiretapping. “I am convinced that the Supreme Court never intended any dictum … to apply to grave matters involving the defense of the nation,” he wrote in a confidential memo authorizing Hoover to wiretap in matters of national security—a vague and open-ended category. A few weeks later, he authorized the FBI to launch intelligence operations in Latin America, where it was feared that the Germans were building an espionage network to prepare for invasion and occupation. And in late June, he signed the Smith Act (formally known as the Alien Registration Act), which required all foreign-born residents to register with the government and outlawed violent revolutionary language.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/d2/37d2a511-f470-4f26-a7a2-996b35ee72a3/benjamin_j_davis_nywts.jpg)

The director’s top priority, as the reality of the Nazi blitzkrieg sank in, was to contain the supposed “fifth column” threat, the possibility that enemy agents were already operating in the U.S. The issue entailed a blend of fact and fiction, an exaggerated threat accompanied on occasion by a few honest-to-goodness, in-the-flesh foreign spies. He recognized that the issue would produce another round of upheaval at the bureau, requiring “the utmost from the facilities and personnel of this organization.” There was something familiar about the situation, though, with its sudden demands to scale up bureau personnel against a backdrop of national unease. In his annual report to the attorney general, Hoover likened this “period of transition” to the first years of the New Deal crime war, when he had transformed his corps of gentleman lawyers into gun-toting G-Men. Only now the bureau would have to remake itself as a large-scale intelligence agency, capable of forging judgments that went well beyond matters of legal evidence and criminal law.

Many of the duties that fell to the bureau were relatively new, requiring each division to adapt its criminal enforcement background to the exigencies of the country’s pseudo-war. The FBI lab underwent an abrupt shift, transforming itself from a criminal forensics facility into a wartime intelligence lab, focused on secret inks and microfilm technology and high-resolution cameras. At the Identification Division, what had once been a clearinghouse for criminal fingerprints evolved into a large-scale domestic surveillance program, compiling the prints of draftees, war-production workers and foreign-born residents.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/a1/71a1731c-6a53-42a5-ab34-f0dcd5d656ab/1024px-_appreciate_america_stop_the_fifth_column__-_nara_-_513873.jpeg)

The bureau’s accountants turned their attention from securities fraud to the monitoring of foreign funds. Building on the work of the General Intelligence Division, Hoover organized a new National Defense Division and continued to expand surveillance of “German groups and sympathizers, communist groups and sympathizers, fascist groups and sympathizers, Japanese and others.” Field offices opened in Hawaii, Alaska and Puerto Rico. A small number of agents also shipped out to foreign posts on “undercover assignments for intelligence purposes.”

Hoover vowed that wartime pressures would not weaken his hiring standards or significantly alter the culture of the FBI. But he quickly ran into a numbers problem. By the middle of 1941, the bureau was hiring 52 agents every two weeks, plus more than 160 clerks and stenographers. The sheer scale of the effort necessitated a quiet easing of his preference for college- and fraternity-bred lawyers and accountants, though he remained firm in his policy not to hire women or Black men as agents. In January 1940, the FBI employed 2,432 people. By February 1941, it had 4,477 employees, with plans to reach 5,588 by June. To fund this expansion, Congress provided money, more of it than Hoover had ever seen. In fiscal year 1941, his budget was more than $14 million. The following year, it leapt to $25 million. And the U.S. war effort was just getting started.

Hoover’s response to this sudden rush of money, power and personnel partially fulfilled the dark warnings proffered by civil libertarians just a few months earlier. Roosevelt’s wiretapping directive allowed the FBI to launch surveillance of foreign diplomats; by early fall, taps were up and running at the German, French, Italian, Russian and Japanese embassies. The directive also gave Hoover wide latitude to decide who else needed to be watched. In his view, the category of “subversive” included virtually anyone who expressed sympathy toward a foreign power or hostility to the war effort, including striking workers and critics of White House policy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/83/6f/836f786f-86a6-49ba-b39d-3787654765ba/1920px-director_hoover_1940_office.jpeg)

“None of these persons today has violated the specific federal law now in force and effect,” Hoover acknowledged, “but many of them will come within the category for internment or prosecution as a result of regulations or laws which may be enacted in the event of a declaration of war.” Unlike criminal law enforcement, in which police gathered evidence after a crime had been committed, wartime surveillance was supposed to be a preventive endeavor. “To wait until [a declaration of war] to gather such information or to conduct such investigations would be suicidal,” the director wrote.

Hoover jealously guarded the bureau’s right to recruit informants and conduct surveillance within any group that might conceivably disrupt the war effort, including labor unions. The year 1941 produced a wave of unrest in key defense industries—aviation, electronics, automobile, coal—where Communist Party members had helped to establish powerful unions in recent years. Hoover knew enough about New Deal alliances to insist that “I, of course, have no controversy with bona fide organized labor.” But he maintained that the Communist Party—guided by the spirit of the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact—was fomenting industrial conflict to disrupt the American war effort, thus providing the logic for an ongoing program of labor surveillance. “I fully realize that the bureau in initiating and carrying on investigations in this field must follow a very careful course between ‘Scylla and Charybdis’ and that undoubtedly some sources will accuse the bureau of illegal activities,” he wrote to Jackson in spring 1941, positioning himself as a martyr to the cause of national security. “I believe, however, that we must have the courage to face the yelping of these alleged liberals.”

The tug of war over homegrown radicalism was well known to Hoover, a struggle that he had first engaged more than 20 years before. Other aspects of his work took him into more distant terrain, where he was less sure of his direction. The bureau’s move into wartime intelligence did not require simply scaling up. It also necessitated a change in mentality and a shift in the bureau’s culture. From 1924 to 1940, Hoover had focused on turning the bureau into a model of professional law enforcement. Now he was supposed to transform it into a major international intelligence and counterespionage agency capable of gathering secret information about enemy spies and, where possible, thwarting their activities.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/8a/368aaee8-79b0-45e0-9d19-35a85b5470b9/fdr-september-30-1934.jpeg)

This proposition did not easily lend itself to Hoover’s emphasis on statistics and publicity. Spies rarely take credit for their achievements; the best operations remain, by definition, secret. Spies let investigations run for months, even years, without knowing whether anything is really being accomplished. Successful espionage requires cunning and deceit, sometimes involving relationships with unsavory characters. None of this came naturally to Hoover. And there was almost nobody within the U.S. government from whom he could learn. As an FBI report later noted, the bureau plunged into counterespionage work that summer “under extreme difficulties and without any precedent whatsoever to follow with regard to this type of work.”

The experience would no doubt have been far more difficult if not for the help of the one group on American soil that knew a great deal about such matters: the British intelligence service. The British had reached out to Hoover as the war ramped up. Though the Battle of Britain lay months in the future, by the spring of 1940, they were growing anxious about American foot-dragging and the bitter isolationist sentiments of such men as aviator Charles Lindbergh. Prime Minister Winston Churchill made no secret of his determination to bring the U.S. into the war, and he hoped to promote this aim by setting up a British intelligence outpost in New York. From there, his proxies could agitate on behalf of Britain and help the Americans build the clandestine infrastructure that would be needed for full-scale war. Churchill’s vision was extralegal; no nation in the world openly allowed a foreign power to run an intelligence service on domestic soil. To make it happen, the British decided they needed Hoover’s assistance and permission.

He agreed to the proposition. With British approval, Hoover dispatched FBI official Hugh Clegg to London for a round of training in espionage and counterespionage techniques. Several months later, he sent Percy Foxworth, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s New York office and now the head of operations in Latin America. Agents themselves were periodically dispatched to Camp X, a secret British-run guerrilla and spy training ground just outside Toronto. There, the British drilled hundreds, then thousands of Canadian, British and American citizens in the arts of sabotage, self-defense and secret codes. According to one report, Hoover himself snuck across the border to visit Camp X and nearly fainted at the sight of German warships amassing on Lake Ontario, though it turned out to be a mirage created through specially positioned mirrors and stage sets—a bravura performance by Britain’s experts in duplicity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/e8/45e8eaf6-b76c-4f83-a5c9-ddfa1f2d2a6c/hermann_goering_gives_charles_lindbergh_a_nazi_medal.jpeg)

In a postwar assessment, British analysts expressed skepticism about the FBI’s accomplishments in the realm of intelligence. “The FBI [was] devoted to traditional police methods, brought up to date by lavish expenditure on laboratory and other technical equipment,” a British report explained. “These methods, though admirably suited to crime detection, were sometimes found to be quite inappropriate to the efficient conduct of counterespionage.”

Still, they admired Hoover’s dogged approach, in which he attempted to learn the entire spy trade in just a few months’ time. “J. Edgar Hoover is a man of great singleness of purpose,” the report concluded, “and his purpose is the welfare of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

From G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century by Beverly Gage, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Beverly Gage.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/beverly.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/beverly.png)