Hypatia, Ancient Alexandria’s Great Female Scholar

An avowed paganist in a time of religious strife, Hypatia was also one of the first women to study math, astronomy and philosophy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hypatia-murdered-631.jpg)

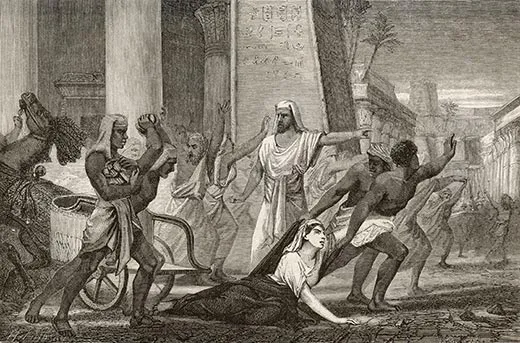

One day on the streets of Alexandria, Egypt, in the year 415 or 416, a mob of Christian zealots led by Peter the Lector accosted a woman’s carriage and dragged her from it and into a church, where they stripped her and beat her to death with roofing tiles. They then tore her body apart and burned it. Who was this woman and what was her crime? Hypatia was one of the last great thinkers of ancient Alexandria and one of the first women to study and teach mathematics, astronomy and philosophy. Though she is remembered more for her violent death, her dramatic life is a fascinating lens through which we may view the plight of science in an era of religious and sectarian conflict.

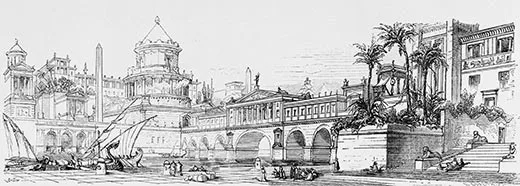

Founded by Alexander the Great in 331 B.C., the city of Alexandria quickly grew into a center of culture and learning for the ancient world. At its heart was the museum, a type of university, whose collection of more than a half-million scrolls was housed in the library of Alexandria.

Alexandria underwent a slow decline beginning in 48 B.C., when Julius Caesar conquered the city for Rome and accidentally burned down the library. (It was then rebuilt.) By 364, when the Roman Empire split and Alexandria became part of the eastern half, the city was beset by fighting among Christians, Jews and pagans. Further civil wars destroyed much of the library’s contents. The last remnants likely disappeared, along with the museum, in 391, when the archbishop Theophilus acted on orders from the Roman emperor to destroy all pagan temples. Theophilus tore down the temple of Serapis, which may have housed the last scrolls, and built a church on the site.

The last known member of the museum was the mathematician and astronomer Theon—Hypatia’s father.

Some of Theon’s writing has survived. His commentary (a copy of a classical work that incorporates explanatory notes) on Euclid’s Elements was the only known version of that cardinal work on geometry until the 19th century. But little is known about his and Hypatia’s family life. Even Hypatia’s date of birth is contested—scholars long held that she was born in 370 but modern historians believe 350 to be more likely. The identity of her mother is a complete mystery, and Hypatia may have had a brother, Epiphanius, though he may have been only Theon’s favorite pupil.

Theon taught mathematics and astronomy to his daughter, and she collaborated on some of his commentaries. It is thought that Book III of Theon’s version of Ptolemy’s Almagest—the treatise that established the Earth-centric model for the universe that wouldn’t be overturned until the time of Copernicus and Galileo—was actually the work of Hypatia.

She was a mathematician and astronomer in her own right, writing commentaries of her own and teaching a succession of students from her home. Letters from one of these students, Synesius, indicate that these lessons included how to design an astrolabe, a kind of portable astronomical calculator that would be used until the 19th century.

Beyond her father’s areas of expertise, Hypatia established herself as a philosopher in what is now known as the Neoplatonic school, a belief system in which everything emanates from the One. (Her student Synesius would become a bishop in the Christian church and incorporate Neoplatonic principles into the doctrine of the Trinity.) Her public lectures were popular and drew crowds. “Donning [the robe of a scholar], the lady made appearances around the center of the city, expounding in public to those willing to listen on Plato or Aristotle,” the philosopher Damascius wrote after her death.

Hypatia never married and likely led a celibate life, which possibly was in keeping with Plato’s ideas on the abolition of the family system. The Suda lexicon, a 10th-century encyclopedia of the Mediterranean world, describes her as being “exceedingly beautiful and fair of form. . . in speech articulate and logical, in her actions prudent and public-spirited, and the rest of the city gave her suitable welcome and accorded her special respect.”

Her admirers included Alexandria’s governor, Orestes. Her association with him would eventually lead to her death.

Theophilus, the archbishop who destroyed the last of Alexandria’s great Library, was succeeded in 412 by his nephew, Cyril, who continued his uncle’s tradition of hostilities toward other faiths. (One of his first actions was to close and plunder the churches belonging to the Novatian Christian sect.)

With Cyril the head of the main religious body of the city and Orestes in charge of the civil government, a fight began over who controlled Alexandria. Orestes was a Christian, but he did not want to cede power to the church. The struggle for power reached its peak following a massacre of Christians by Jewish extremists, when Cyril led a crowd that expelled all Jews from the city and looted their homes and temples. Orestes protested to the Roman government in Constantinople. When Orestes refused Cyril’s attempts at reconciliation, Cyril’s monks tried unsuccessfully to assassinate him.

Hypatia, however, was an easier target. She was a pagan who publicly spoke about a non-Christian philosophy, Neoplatonism, and she was less likely to be protected by guards than the now-prepared Orestes. A rumor spread that she was preventing Orestes and Cyril from settling their differences. From there, Peter the Lector and his mob took action and Hypatia met her tragic end.

Cyril’s role in Hypatia’s death has never been clear. “Those whose affiliations lead them to venerate his memory exonerate him; anticlericals and their ilk delight in condemning the man,” Michael Deakin wrote in his 2007 book Hypatia of Alexandria.

Meanwhile, Hypatia has become a symbol for feminists, a martyr to pagans and atheists and a character in fiction. Voltaire used her to condemn the church and religion. The English clergyman Charles Kingsley made her the subject of a mid-Victorian romance. And she is the heroine, played by Rachel Weisz, in the Spanish movie Agora, which will be released later this year in the United States. The film tells the fictional story of Hypatia as she struggles to save the library from Christian zealots.

Neither paganism nor scholarship died in Alexandria with Hypatia, but they certainly took a blow. “Almost alone, virtually the last academic, she stood for intellectual values, for rigorous mathematics, ascetic Neoplatonism, the crucial role of the mind, and the voice of temperance and moderation in civic life,” Deakin wrote. She may have been a victim of religious fanaticism, but Hypatia remains an inspiration even in modern times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)