“I Was Looking Forward to a Quiet Old Age”

Instead, Etta Shiber, a widow and former Manhattan housewife, helped smuggle stranded Allied soldiers out of Nazi-occupied in Paris

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120525115030Etta-web.jpg)

On December 22, 1940, a former Manhattan housewife named Etta Kahn Shiber found herself in Hotel Matignon, headquarters of the Gestapo in Paris, sitting across from a “mousy” man in civilian clothes who said his name was Dr. Hager. Shiber, a 62-year-old widow, planned to follow the advice that had replayed in her head for the past six months—deny everything—but something about the doctor’s smile, smug and imperious, suggested that he didn’t need a confession.

“Well, the comedy is over,” he began. “We now have the last two members of the gang.… And I have just received word that Mme. Beaurepos was arrested in Bordeaux two hours ago. So there really wasn’t any reason to allow you to wander around the streets any longer, was there?”

A clerk appeared to transcribe everything she said. Dr. Hager asked hundreds of questions over the next 15 hours. She answered each one obliquely, being careful to say nothing that could be used against her friends and accomplices, and was escorted to a cell at the Cherche-Midi prison.

As he turned to leave, Dr. Hager smiled and reminded her that the punishment for her crime carried a mandatory sentence of death.

Six months earlier, on June 13, 1940—the day the Nazis invaded Paris—Etta Shiber and her roommate, whom she would identify in her memoir, Paris Underground, as “Kitty Beaurepos,” collected their dogs, jewelry, and a few changes of clothing and started out on Route Nationale No. 20, the broad that connected Paris with the south of France. The women had met in 1925, when Etta was on vacation with her husband, William Shiber, the wire chief of the New York American and New York Evening Journal. They kept in touch, and when her husband died, in 1936, Kitty invited Etta to live with her in Paris. Kitty was English by birth and French by marriage but was separated from her husband, a wine merchant. Etta moved into her apartment in an exclusive neighborhood near the Arc de Triomphe.

Now the city streets were deserted and the highway was choked with thousands of refugees—in autos, on foot, in horse-drawn carts, on bicycles. After twenty-four hours Etta and Kitty were still idling on the outskirts of Paris, and they knew the Germans would soon be following.

They heard them before they saw them: a faint hum gathering force, louder each second, sounding like a thousand poked hives emptying out across the sky. The planes swooped into view, the hum turning into a roar, flames spitting from the nozzles of their guns. Frantic motorists turned their cars into trees and ditches; the few that remained on the road stalled. Then came the rumble of tanks, armored cars, an endless ribbon of officers on motorcycles. One officer pulled up beside their car, and, in perfect French, ordered them to turn around and head back to Paris.

On the way they stopped at an inn. While they ate, the innkeeper lingered near their table, eavesdropping. Finally he approached and asked if they might do him a favor. He did not speak English, and he had a guest who spoke English only. The guest was trying to tell him something, but he couldn’t understand. Might they ask him how long he intends to stay? “I don’t want to ask him to leave,” the innkeeper explained, “but there are Germans all around, they are hunting for Englishmen, and—you understand—it is dangerous for me. I am likely to get into trouble if he stays. Wait here a minute. I will bring him to you.”

William Gray was a British pilot. He had been unable to get to the ships evacuating Dunkirk, but a group of French peasants helped him sneak through German lines. He set out for the south of France, hoping to get below German-held territory, and now he was stranded. Etta was struck by how closely he resembled her brother, who had died in Paris in 1933.

“I don’t want to trouble you ladies,” he said, “but if you would just tell this chap for me to be patient, that I will go as soon as he can get me some civilian clothes, I will be able to take care of myself after that.”

Kitty translated, and both she and Etta were surprised when the innkeeper objected to the idea of civilian clothes. He explained: if Gray were caught wearing his uniform, he would be treated as a prisoner of war. But if he wore civilian clothes, he would be shot as a spy. Gray agreed and said he should try to get out of there as quickly as possible. He thanked them and moved toward the door.

Etta stopped him. She had an idea.

William Gray’s long body filled the luggage compartment of their car, limbs tucked and folded, chin grazing knees. Guards stopped them three times before they reached the Porte d’Orléans, the point from which they had left Paris, and asked to see their papers. With shaking hands they obliged, and were relieved when no one thought to check the trunk.

They hid Gray in their apartment, telling him not to stand near the window or answer the phone, as the German occupation began encroaching on every facet of residents’ lives. Bars, bistros, restaurants and boutiques were shuttered, the only street traffic the clatter of German military vehicles and squads of marching soldiers. The Germans seized some businesses without paying the owners a cent. They purged bookstores and newsstands. Daily house searches yielded numerous Frenchmen of military age and the occasional British civilian or soldier, hiding with friends or relatives or complete strangers. “The first French prisoners went by in trucks through the Place de la Concorde,” one witness reported. “Girls and women ran after them, a few weeping.”

One week into Gray’s stay, a Gestapo agent, flanked by two civilians, knocked on their door. Kitty answered, stalling the men while Etta hustled William into his bedroom. “Quick!” she whispered. “Get off your clothes, and into bed. Pretend you are very ill. Leave the talking to me.” They searched the living room, the kitchen, closets, bathrooms. When they came to the bedroom, Etta stroked Gray’s arm and said, “It’s all right, Irving. Don’t try to talk.” She turned to the Germans and explained that this was her brother.

“His papers, please,” the agent demanded.

Etta rummaged through her bureau and found the red wallet containing her deceased brother’s American passport and green identity card. The agent flipped through the papers, alternating his gaze between the photo and Gray, lying in bed. The agent seemed convinced they were the same man but had one more question. “This card has expired,” he said, holding it aloft. “Why wasn’t it renewed?”

“We intended to go back to America, because of the war,” Etta replied. “We would have gone long ago, if his health had been better. It didn’t seem worth renewing it under the circumstances.”

After the agents left, they poured champagne and drank a toast to their close call.

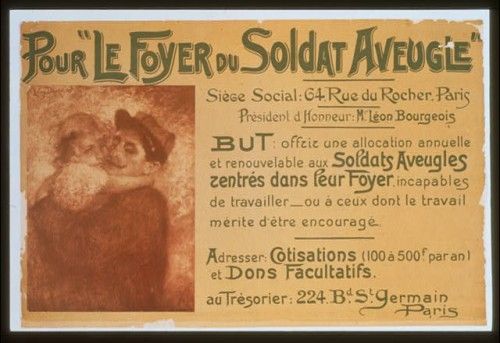

They brainstormed ways to help Gray get back to England. Trains were running from Paris to the unoccupied zone, but guards inspected papers at the border and would be suspicious of someone who spoke no French. They heard of a doctor whose house straddled the line of demarcation. After seeing patients he let them choose to exit by either the front or back door without inquiring which way they had entered, but the Nazis soon caught on to this ruse. Kitty called their friends, but most of them had fled the city, and the women didn’t quite trust most of those who had chosen to stay behind. But she connected with one, Chancel, whom they had met while working for the Foyer du Soldat, a service organization for veterans. He was a true Frenchman, a veteran of the First World War, and would never compromise with the Germans.

They visited Chancel at his small apartment near the Bastille and told him about Gray. “It’s a pity you didn’t come to me at once,” Chancel said, and confided that friends of his had converted their Left Bank home into a refuge for soldiers in hiding. They devised a plan: Etta and Kitty would offer their services to the Foyer du Soldat. They would stick a Red Cross emblem on their car and wrap Red Cross bands around their arms. They would be allotted ten gallons of gasoline per week and have a perfect excuse for moving about the country, taking food and other necessities to prisoners, visiting wounded men in hospitals. They would stow William in their luggage compartment again and smuggle him to the border.

It worked, and the women next placed a carefully worded ad in the “Missing Persons” column of Paris-Soir, whose operations the Nazis had taken over. They hoped that soldiers in hiding, eager for news of the war, would slip into villages whenever possible to read the papers. Some of them would see their notice and understand the subtext: “William Gray, formerly of Dunkirk, is seeking his friends and relatives.” It was safe to use Gray’s name, they figured, since he wasn’t listed on any German records and was out of occupied territory. For a return address, they used the location of a friend’s café on the Rue Rodier.

They were waiting for responses when they heard bad news from Chancel. Someone in his group had betrayed him, and the Gestapo busted his organization. He had to flee to the unoccupied zone long enough to grow a beard to cover his distinctive facial scar; otherwise the Germans would recognize him on sight. When they mentioned their ad in the Paris-Soir, he urged them to scrutinize all responses—Gestapo agents might see the notice and try to set a trap.

They heard from a B.W. Stowe, with a return address in Reims. Etta and Kitty were suspicious—Reims was a large city, and therefore a strange place for a soldier to hide—but the next letter, from the parish priest of the village of Conchy-sur-Canche, seemed legitimate. “I am writing to you at the request of a few of my fellow parishioners,” it began, “who seem to recognize an old friend in you.” He explained that his church building was in need of repair and he was campaigning for a restoration fund. It was signed, “Father Christian Ravier.”

Etta guessed Father Christian to be about 28 and found him “bright-eyed and energetic.” He led them to the rear of his rectory, a soundproof room directly below one occupied by a group of Nazi guards. He said there were at least 1,000 English soldiers hiding in the woods around the village, exhausted and debilitated, “lads in their twenties” dying of old age. They had established a makeshift headquarters deep in the forest, so secluded they were able to elude Nazi motorcycle patrols, and he brought them a radio so they had a connection to the outside world. He had already made arrangements to get the men out of the village a few at time, securing identity cards showing they had permission to go to Paris for factory work. If he transported the soldiers to Paris, would they be able to smuggle them across the lines?

The women assured him they would. Their plans were solidified by the timely reappearance of Chancel, now sporting an unruly black beard and thick spectacles. He offered to provide French escorts for every group of British soldiers, and promised to coach his men on how to handle any emergency.

By the fall they had sent more than 150 English soldiers out of the country, usually in groups of four. “We became so accustomed to it,” Etta wrote, “that we hardly thought any more of the dangers we were incurring,” but an incident in late October rattled her nerves. She opened the apartment door to find Emile, a young boy who collected soldiers’ responses to their advertisement. He told her that Monsieur Durand, the owner of the café, wanted her to come right away. A man calling himself “Mr. Stove” was there, asking to speak with Kitty.

The name sounded strangely familiar, and after a moment Etta realized who Emile meant: Mr. B.W. Stowe, one of the earliest responders to the ad. Kitty was away, traveling through the unoccupied zone to raise money for the cause, so Etta had to deal with the situation alone. She instructed Emile to tell Monsieur Durand to meet her in a restaurant a block from the café.

Durand sat down across from her, making nervous origami with the tablecloth. About an hour earlier, he explained, a man had come into the café. He claimed to be an Englishman who was in “great danger,” seeking a way to escape. He said he’d written a letter to “William Gray” and addressed it to him at the café, but had gotten no response. The man’s English didn’t sound quite right to Durand, but it was his German-accented French that gave him away. That and the fact that he smoked a German military cigarette while they spoke—the kind issued to soldiers.

A few weeks later, when two Gestapo agents came to arrest her, it was, Etta wrote, as if she were acting “in the grip of some cold intensity, some sort of trance. I must have responded to the demands of the moment like an automaton or a somnambulist.” As she passed a hallway mirror, the men following close behind, she was surprised to see that she was smiling.

Etta was charged with “aiding the escape into the free zone of military fugitives.” Her status as an American citizen spared her the death penalty; the United States had not yet entered the war, and the Germans were reluctant to provoke its government. She was sentenced to three years of hard labor. Chancel got five years, but Kitty and Father Christian were sentenced to death. “Don’t worry about me,” Kitty told her after the trial. “Promise me that you will never think of me sadly. I am not sad. I did what I had to do. I knew the price, and I am willing to pay it. I have given England back one hundred fifty lives for the one she is losing now.” It was the last time they saw each other. In 1943, as Paris Underground went to press, Etta hoped Kitty had avoided execution, but she never learned of her friend’s fate.

She was consoled by the news that Father Christian had outwitted the Germans once again. Four weeks after his trial, the prison was notified that Nazi officers would call for him the day before his scheduled execution. At the appointed time, two such officers arrived with an order for his delivery and took him away. An hour later two more officers arrived—and realized that the earlier emissaries were actually agents with the British Secret Service. The priest resurrected the smuggling operation.

Etta served a year and a half of her sentence, languishing in Fresnes Prison, sick and malnourished. She was exchanged in May 1942 for Johanna Hofmann, a hairdresser on the German super-liner Bremen who had been convicted of being a member of a German spy ring in America. Back home in New York City, Etta was surprised when strangers tried to lionize her. “I didn’t know how to take so much attention,” she told a reporter in 1943, five years before her death. “The Nazi invasion did it—not I. I was looking forward to a quiet old age. I still am.”

Sources:

Books: Etta Shiber, Paris Underground. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1943; James Owen and Guy Walters (Editors), The Voice of War. New York: Penguin Press, 2005; Charles Glass, Americans and Paris: Life and Death Under Nazi Occupation. New York: Penguin Press, 2010; Alan Riding, And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

Articles: “Germans Couldn’t Stop French Resistance.” The Washington Post, August 10, 1965; “Liberties of Paris Purged.” Los Angeles Times, October 17, 1940; “American Women in France.” The Manchester Guardian, December 16, 1940; “American Woman Held in Paris by Nazis for ‘Aiding Fugitives.’” Boston Globe, February 15, 1941; “Mrs. Shiber Dies; Nazi Foe in War.” New York Times, December 25, 1948; “Elderly American Woman Headed Amateur Underground in France.” The Brownsville Herald, October 15, 1948; “Nazis Free U.S. Woman.” New York Times, May 28, 1942; “U.S. Woman Nabbed By Gestapo For Aiding British, Home Again.” The Evening Independent (Massillon, Ohio), December 9, 1943; “Nazis Sentence Widow of Former New York Editor.” The Washington Post, March 16, 1941; “Woman Author Has Dangerous Adventures In Occupied Paris.” Arizona Republic, November 21, 1943.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)