In Damascus, Restoring Beit Farhi and the City’s Jewish Past

An architect works to restore the grand palace of Raphael Farhi, one of the most powerful men in the Ottoman world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/sitting-area-of-Beit-Mourad-Farhi-631.jpg)

Ghosts inhabit Damascus’ Old City like players on a stage. You can see them peering through the ramparts of the citadel and tending to the faithful at the Omayyad Mosque. In the narrow passageways of the main souk, they clamor among the spice markets and connive between the caravansary and Byzantine colonnade.

You can see them. There is the Ottoman Governor As’ad Pasha al-Azem, receiving visitors and hearing petitions in the salamlik of his palace, a Mamlukian treasure. Across the way is a merchant from Andalusia offering textiles from Pisa for a set of Persian ceramics. At the Burmistan al Nur, or “house of patients,” a group of surgeons are gathered under a kumquat tree for a lecture on the latest techniques of scapulimancy – a method of divination – from Toledo, Spain. And here among litter of citrus fruit, chatting among shop owners and munching on Arab pastry, is the cunning and charismatic Mu’awiya – the caliph himself – so secure in his authority he is attended by only a single bodyguard.

But the real power center in Old Damascus – indeed, in the whole empire – is a few hundred yards away, off Al-Amin Street in the old Jewish Quarter. That would be Beit Farhi, the grand palace of Raphael Farhi, the successful banker and chief financial adviser to the Ottoman sultanate. It was Raphael and his older brother, Haim, who collected the taxes that financed the granaries, foundries and academies of Greater Syria, and it was the subterranean vaults of his palace that held the gold that backed the imperial coin. Until his family’s tragic dissolution in the mid-19th century, Raphael Farhi – known as “El Muallim,” or the teacher – was not simply the leader of Syria’s famously prominent and prosperous Jewish community; He was one of the most powerful men in the Ottoman world.

Hakam Roukbti knows this better than anyone. As the architect who has assigned himself the epic task of restoring Beit Farhi to its former glory, he has been working with a full complement of ghosts – Raphael, his brothers and their extended families, the palace guests and servants – peering over his shoulder. “The Farhis controlled all the finances in Greater Syria,” says Roukbti. “He was paying the pashas’ salaries. He appointed governors. This house was the most important of all the houses in Damascus.”

Roukbti, a Syrian who left for Spain in 1966 to study Islamic art, and his wife, Shirley Dijksma, have devoted themselves to the faithful renovation of the massive and labyrinthian Beit Farhi -- from the Hebrew language inscriptions carved in the reception hall to the orange trees in the courtyards. Their goal is to complete the work this summer and launch it as a luxury boutique hotel not long after that.

It is all part of a wider renaissance in one of the longest-inhabited cities in the world. While an economic boom is transforming greater Damascus into a modern metropolis with five-star hotels and shopping malls, the old city is keeping true to itself. Villas and caravansary are being carefully restored and converted into restaurants, cafés, inns, and art salons. Even the usually absent municipal government is getting into the act; the citadel has been completely renovated and strips of the souk’s narrow streets have been appointed with gas lamps.

At the epicenter of this reawakening is Beit Farhi, all 25,000 square feet of it. The rooms are nearly finished, complete with spot lighting and central heating, and soon the reception hall will be sealed under a glass canopy that will protect guests from the city’s pollution and insects. (It was one concession Roukbti made to modernity.) The cellar bar, which will stretch along the entire north side of the palace, is poised to become a favored watering hole of Damascus’ well-fixed expatriates. It was dug out at a price, however; according to Dijksma, an interior designer who promotes local Syrian artists, the same laborer was bitten three times by scorpions.

But while Beit Farhi may soon be hosting international film stars and celebrity politicians in its pricey chambers, it is far more than a commercial enterprise. The Muslim Roukbti and the Christian, Dutch-born Dijksma are on a mission that is as much ecumenical as aesthetic. The Syrian Jewish population has a history, as lush and complex as Beit Farhi’s marble-inlaid floors, that begins on one end of the Mediterranean and ends on the other. For centuries, it was a vital part of the mosaic of varied religions and ethnicities that made Damascus the world’s first city of commerce and culture.

For decades, the Jewish quarter has been a mute stepchild to the perennially chaotic main souk. Emptied after the creation of Israel and the wars that followed, its apartments and stalls have been padlocked by families now living elsewhere.

Today, the remains of Syria’s Jewish community consist of about three dozen aged men and women in Damascus and even fewer in the northern city of Aleppo. Albert Cameo, a leader of Syria’s residual Jews, recalls with delight the day Roukbti introduced himself as the man who was going to save Beit Farhi. “I assumed he was crazy,” Cameo says above the din of workers sanding stone walls in preparation for painting. “But then I thought, ‘What does it matter if he can pull it off?’ And now, look at this miracle.”

Cameo, who like many Sephardic Jews – including the Farhis – has roots in Moorish Spain, grew up in a house just a few blocks away. He remembers his parents telling him stories about the Farhis and the great palace and how its library was open to any Jew who wanted to read from its many volumes. Cameo’s recollections and those of his contemporaries have helped Roukbti in his restoration.

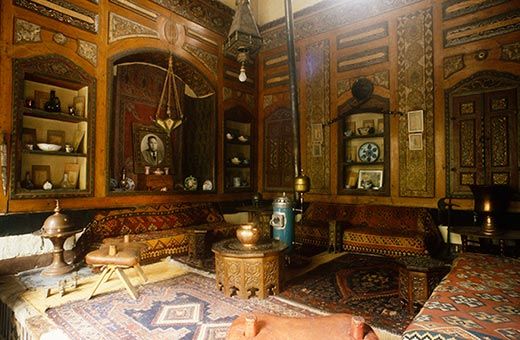

There are also written accounts from 19th-century visitors like Lady Hester Stanhope, the famous traveler and Orientalist, who described the palace’s five inner courtyards, opulent gilded walls and gold-studded coffee cups. John Wilson, a noted biblical scholar of his day, wrote of the palace as “a little like a village … [with] sixty or seventy souls. The roof and walls of the rooms around the court are gorgeous to a high degree.” Wilson wrote of the Farhi’s grand hospitality and he detailed the palace libraries, both the public one and Raphael’s private book collection, in admiring detail.

For the purposes of restoration, however, these accounts lacked depth. Roukbti and Dijksma had only one visual source that depicted Beit Farhi at its apex: an 1873 rendering of the palace’s main courtyard by the classicist painter Sir Frederick Leighton. Titled Gathering Citrons, it portrays a woman in lavish robes looking on as an attendant drops fruit plucked from an orange tree into the outstretched hem of a young girl’s skirt. The stone columns are painted in alternating stripes of apricot and blue and the arches are enameled with intricate ceramic designs.

It is a charming tableau – and a far cry from Beit Farhi’s condition when Roukbti bought it in 2004. (A successful Paris-based architect, Roukbti financed the purchase with the help of several partners.) Like so much of the largely evacuated Jewish quarter, the palace was a nesting place for squatters. More than a dozen families, mostly Palestinian refugees, were living in each of its many rooms and it took Roukbti six months to buy them out under Syrian law. The main reception hall, which the Farhis used as their personal synagogue, had been ransacked and burned by looters decades earlier. Even the fountain had been dug up and carried away. It took another six months to clear the debris and crumbled stone from years of neglect and plundering before the real work could begin.

Whenever possible, Roukbti and Dijksma drew from indigenous sources to complete their work. The stones were quarried locally, though some of the marble was imported from Turkey and Italy. The pigmentation powder used in recreating Beit Farhi’s iconic ochers and azures was obtained from nearby shops. They recruited dozens of young artisans to repair or recreate from scratch the elaborately carved wood ceilings, marble floors and delicate frescoes. “It was difficult to find them,” says Roukbti, who has an artist’s easy manner and a thick head of grizzled black hair. “And even then, I had to be on top of them all the time. But now they are highly skilled. This has been like a finishing school.”

The work site has the quality and feel of an archaeological dig. The foundation of Beit Farhi begins with a layer of roughly hewn stones cut during the Aramaic period beneath far more precise masonry typical of Roman construction. The area was occupied by modest dwellings of black stone before the Farhis arrived in 1670 from the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, where they lived for two centuries after King Ferdinand expelled the Jews from Spain in 1492.

“They came with money,” says Roukbti. “And they came with powerful connections with Ottoman authorities.”

It was the dawn of a powerful Syrian dynasty that lasted some 200 years. During Napoleon Bonaparte’s advance on Palestine in 1799, Haim Farhi is credited by Jewish historians for having rallied the Jews of Acre in a successful resistance. An ambitious pasha had him killed in 1824, however, and a reprisal attack led by Raphael ended in failure with the loss of his brother, Solomon.

Despite Haim’s death, the Farhis would enjoy unrivaled wealth and power over the next two decades with Raphael as treasurer and vizier to the sultanate. But his fortunes were undone in 1840 by the family’s association with the suspected murder of a Franciscan monk. Several of Damascus’ most prominent Jews were arrested in the matter, including a Farhi family member, and it took intercessions from high-ranking diplomats and officials – all the way up to Mohammed Ali, the rogue Ottoman ruler of Egypt and the Levant - to clear them of wrongdoing. The affair was a mortal disgrace for the Farhis, however, and they scattered themselves about the capitals of the world.

At the very least, Roukbti hopes the rebirth of Beit Farhi will redeem Syria’s Jewish heritage - if not the Farhis themselves. Already, according to Cameo, two groups of Jews from abroad have visited the site and he is eager to host more. “This house has suffered so much,” he says. “Its return is very important, not just for Syria’s Jews but for all Syrians.”