In Defense of King George

The author of a new biography shines a humane light on the monarch despised by the colonists

:focal(400x301:401x302)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/d6/58d67c9a-dbb1-4712-9f46-58d1a6229fb4/george.jpg)

Since 2015, Queen Elizabeth II has released more than 100,000 pages of documents in the Royal Archives relating to King George III. They reveal a startlingly new picture of the last king of America—one about as far removed as possible from the description of George in the Declaration of Independence: “A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

We can now see, for example, George’s fervent denunciation of slavery in an essay he wrote as Prince of Wales in the late 1750s, after reading Charles de Montesquieu’s classic enlightenment text, The Spirit of the Laws (1748). Indeed, George’s comments go even further than Montesquieu’s own opposition to the practice.

“The pretexts used by the Spaniards for enslaving the New World were extremely curious,” George notes; “the propagation of the Christian religion was the first reason, the next was the [Indigenous] Americans differing from them in colour, manners and customs, all of which are too absurd to take the trouble of refuting.” As for the European practice of enslaving Africans, he wrote, “the very reasons urged for it will be perhaps sufficient to make us hold such practice in execration.”

George never owned slaves himself, and he gave his assent to the legislation that abolished the slave trade in England in 1807. By contrast, no fewer than 41 of the 56 signatories to the Declaration of Independence were slave owners.

It was the Declaration that established the myth that George III was a tyrant. Yet George was the epitome of a constitutional monarch, deeply conscientious about the limits of his power. He never vetoed a single Act of Parliament, nor did he have any hopes or plans to establish anything approaching tyranny over his American colonies, which were among the freest societies in the world at the time of the Revolution: Newspapers were uncensored, there were rarely troops in the streets and the subjects of the 13 colonies enjoyed greater rights and liberties under the law than any comparable European country of the day.

George III’s generosity of spirit came as a surprise to me as I researched in the Royal Archives, which are housed in the Round Tower at Windsor Castle. Even after George Washington defeated George’s armies in the War of Independence, the king referred to Washington in March 1797 as “the greatest character of the age,” and when George met John Adams in London in June 1785, he told him, “I will be very frank with you. I was the last to consent to the separation [between England and the colonies]; but the separation having been made, and having become inevitable, I have always said, and I say now, that I would be the first to meet the friendship of the United States as an independent power.” (The encounter was very different from the one depicted in the miniseries “John Adams,” in which Adams, played by Paul Giamatti, is treated dismissively.)

As these voluminous papers make clear, neither the American Revolution nor Britain’s defeat can be blamed on George, who acted throughout as a restrained constitutional monarch, closely following the advice of his ministers and generals.

I had long assumed that the mental illness that “Mad King George” suffered throughout his reign—at almost 60 years, the longest of any British king—was the result of the rare blood disorder porphyria, which was the generally accepted diagnosis for half a century. Yet it turns out that this conclusion was based on a highly selective list of the king’s symptoms, which Ida Macalpine and her son Richard Hunter, both psychiatrists, presented in the 1960s, arguing strenuously for the diagnosis in journals on both sides of the Atlantic. In fact, leading medical experts have come to agree over the past decade that George III almost certainly suffered from bipolar disorder. In our more enlightened age, we can sympathize much more closely with the horror of his situation: He was a helpless spectator to his own mental deterioration.

The time has therefore come for objective Americans to take a fresh look at their last king. It was right for the colonies to break away from the British Empire in 1776 because they were ready by then to found their own nation-state, but despite the rhetoric of their founding document, they were not escaping tyranny, so much as bravely grasping their sovereign independence from a good-natured, cultured, enlightened and benevolent monarch.

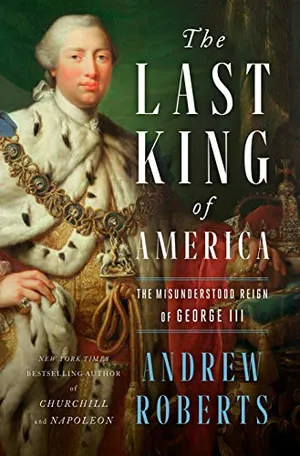

Adapted from The Last King of America by Andrew Roberts, to be published on November 9, 2021, by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021

The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III

The last king of America, George III, has been ridiculed as a complete disaster who frittered away the colonies and went mad in his old age. The truth is much more nuanced and fascinating—and will completely change the way readers and historians view his reign and legacy.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.