In Iraq, a Monastery Rediscovered

Near Mosul, war has helped and hindered efforts to excavate the 1,400-year-old Dair Mar Elia monastery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/iraqmonestary_631_new.jpg)

Editors' note, January 21, 2016: According to news reports this week, satellite images have confirmed that militants from the Islamic State destroyed Dair Mar Elia, Iraq's oldest Christian monastery. “Nothing can compensate the loss of such heritage,” Yonadam Kanna, a Christian member of Parliament tells the New York Times.

A soldier scaled the fragile wall of the monastery and struck a pose. His buddies kept shouting up to him to move over some.

He shifted to the left and stood the stadia rod straight to register his position for the survey laser on the tripod below.

The 94th Corps of Engineers of Fort Leonard Wood, whose members normally sprint to their data points in full body armor and Kevlar helmets, are making a topographical map of the ancient Assyrian monastery that until recently had been occupied by the Iraqi Republican Guard and then by the 101st Airborne Division in the once verdant river valley near Mosul.

The Dair Mar Elia Monastery is finally getting some of the expert attention that the 1,400-year-old sacred structure deserves. These days it is fenced in and a chaplain regularly guides soldiers at Forward Operating Base Marez on tours of the ruins. The topographical mapping is part of a long-term effort to help Iraqis become more aware of the site and their own cultural preservation.

"We hope to make heritage accessible to people again," explains Suzanne Bott, cultural heritage adviser for the provincial reconstruction team in Mosul. "It seems pretty clear from other postwar reconstruction efforts, people need some semblance of order and identity" returned to them.

The provincial reconstruction team coordinated a trip for the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage to visit and appraise the key archaeological sites in Ninewa Province, such as Hatra, with its distinctive Hellenic arches, and Nimrud, home of the famous statues of winged bulls.

This past May, Iraqi archaeologists were able to visit the areas for the first time since the start of the war. While sites like the carved walls of Nineveh were in drastic need of protection from the sun and wind, the fact that many areas were largely unexcavated probably protected them from looters, according to Diane Siebrandt, cultural heritage officer for the U.S. State Department in Baghdad. Treasures like the famed gold jewelry of the tombs in Nimrud were transferred from the Mosul museum to a bank vault in Baghdad before the invasion.

The Dair Mar Elia Monastery (or the Monastery of St. Elijah) was not so protected. It was slammed by the impact of a Russian tank turret that had been fired upon by a U.S. missile as the 101st Airborne charged across the valley against the Republican Guard during the initial invasion in 2003. Then it was used as a garrison by the 101st engineers. Shortly after, a chaplain recognized its importance, and Gen. David Petraeus, then the 101st commander, ordered the monastery to be cleared and for the Screaming Eagle emblem to be wiped off the inner wall of the courtyard.

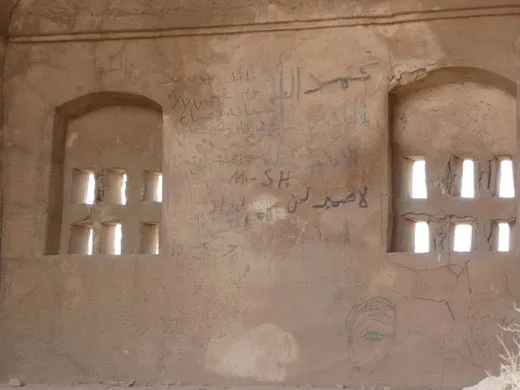

The eastern wall has concaved where the tank turret lifted into the brick and mortar. Inside the plain walls of the chapel, one shell-shaped niche is decorated with intricate carvings and an Aramaic inscription asks for prayers of the soul of the person interred beneath the walls. Shades of a cobalt blue fresco can be found above the stepped altar. Graffiti penned by U.S. and Iraqi soldiers is scrawled in hard-to-reach places throughout. Shards of pottery of an undetermined age litter what might have been a kiln area. Only the stone and mud mortar of the walls themselves seem to remain as strong as the surrounding earth mounds, which may contain unexcavated monk cells or granaries, Bott says.

The topographical mapping will enable Iraqi archaeologists to peel back the layers of decay on the fortress-like house of worship with the early initials of Christ—the symbols of chi and rho—still carved into its doorway. It was constructed by the Assyrian monks in the late sixth century and later claimed by the Chaldean order. In 1743 the monks were given an ultimatum by Persian invaders and up to 150 were massacred when they refused to abandon their cells.

After World War I, the monastery became a refugee center, according to chaplain and resident historian Geoff Bailey, a captain with the 86th Combat Support hospital. Christians supposedly still came once a year in November to celebrate the feast of St. Elijah (also the name of the monastery's founding monk).

Because it became incorporated into the Iraqi Republic Guard base during the 1970s, professors from the school of archaeology at the University of Mosul had a limited awareness of its existence, but the monks of nearby Al Qosh have an oral and written memory of Dair Mar Elia, says Bott, who recently visited the monks.

Excavation and radio carbon dating would help transform the monastery into a truly understood historical site, but to do that the provincial reconstruction team needs both support from outside archaeological institutions like the renowned University of Mosul, the University of Chicago, which has experience in Ninewa, and more importantly the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage. International nongovernmental organizations like UNESCO have also expressed interest in Ninewa since Hatra is listed as a World Heritage Site.

Security is a stumbling block in all cases. The archaeology students from the University of Mosul were invited inside the secure U.S. base to work on the monastery excavation, says Diane Crow, a public diplomacy officer in Mosul. Then, in June, a dean in the College of Agriculture was assassinated. Crow says she's hopeful she can persuade students and professors to come in the fall.

"It's not that people don't want to preserve the sites, it's that right now they're scared. I don't know if someone who's not here right now can understand that or not," Crow says.

In the sense of its ecumenical and tumultuous passage, the St. Elijah Monastery is emblematic of Ninewa Province, still caught in the deadly struggle between insurgents and Iraqi security forces backed by the U.S. 3rd Artillery Regiment, which currently patrol the ancient city.

The first day on patrol with the 3/3rd ACR we passed churches and mosques along the Tigris. The second day we witnessed a car bombing that killed and wounded Iraqis in an attempt to target a senior Iraqi Army commander. Mosul is still as violent as it is beautiful, although attacks against U.S. soldiers have decreased significantly in recent months since the Iraqi-led Operation Lion's Roar.

"There's always the perception that Mosul is falling," says Capt. Justin Harper of Sherman, Texas, who leads a company of soldiers on regular patrols to support the Iraqi Police. "Mosul is not falling. The enemy is trying all the actions it can, but if anything, the government is legitimized in how it can respond."

For the soldiers back on base who get to tour the Dair Mar Elia, it puts a human face on Iraq, Bailey explains. "They see not just a place of enemies. They also see cultural traditions and a place to respect."

"This is how progress is actually measured when it is considered against the backdrop of millennia," Bott says. By the end of the week, the ancient monastery will be transformed into a three-dimensional CAD model for future generations of Iraqis who will hopefully soon have the security to appreciate it.