Industrial Espionage and Cutthroat Competition Fueled the Rise of the Humble Harmonica

How a shrewd salesman revolutionized the instrument industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/98/f8/98f80bee-dd24-42c1-93ca-5972babb3873/1024px-hohner_band_harmonica.jpg)

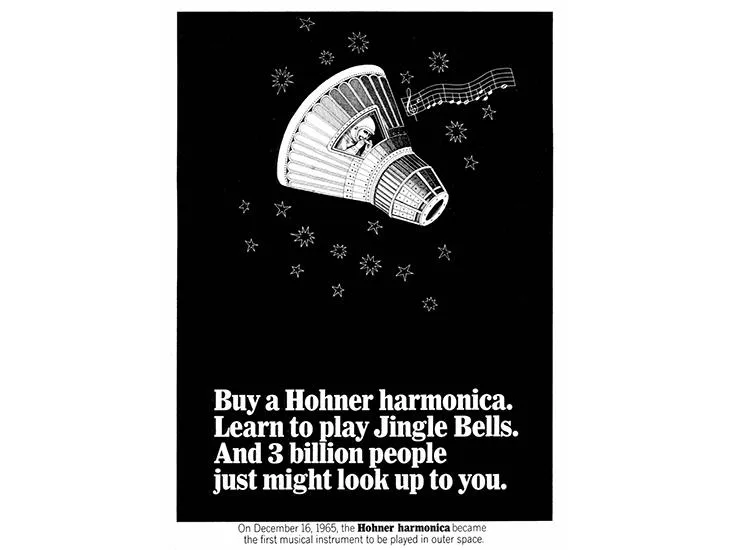

The first song played in space was performed on a musical instrument that weighed just half an ounce and could only make seven notes. In December 1965, while NASA's Gemini 6 was speeding through an orbit of the Earth, astronaut Tom Stafford informed Mission Control that he had spotted some sort of UFO. It was piloted, he reported, by a jolly man in a red suit. His fellow astronaut Wally Schirra pulled out a Hohner “Little Lady” harmonica, and began to play a tinny rendition of “Jingle Bells.”

From humble origins in the workshops of 19th-century Austria and Germany, the harmonica has quite literally circled the world. The instrument's sturdiness and portability—which made it the perfect instrument to smuggle past NASA technicians—were ideal for musicians on the road or on a budget. Their versatility made them just as well-suited to a cheery Christmas carol as to a wrenching bend in a blues ballad. So it's no accident that the harmonica is now a staple of vastly different musical traditions, from China to Brazil to the United States. “You cannot carry a piano,” says Martin Haeffner, a historian who directs the Deutsches Harmonika Museum in Trossingen, Germany. “But a little harmonica you can carry everywhere!”

You can't account for the immodest ascent of the modest harmonica without the story of one man—Matthias Hohner, an industrialist of instruments, a Black Forest clockmaker turned cutthroat businessman.

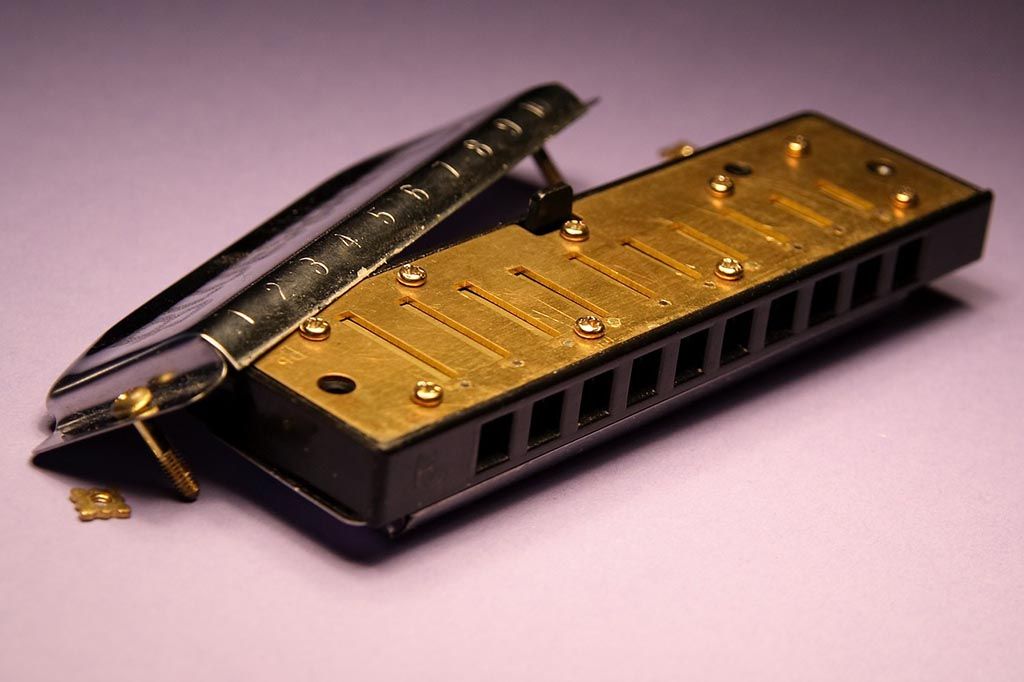

European harmonicas likely descended from Asian instruments imported during the 18th-century (though it's also possible that they were independently invented). Both types of instrument are based on a principle that dates back thousands of years: when air passes over a flat metal “reed”—which is fixed on one end but free on the other—the metal vibrates and produces a sound. One of the first instruments to use this technique is the Chinese sheng, which is mentioned in bone inscriptions from 1100 BCE, and the oldest of which was excavated from the tomb of a 5th-century BCE emperor. When you hear the twangy hum of a harmonica, the pure tones of a pitch pipe, or the rich chords of an accordion, you're hearing the vibrations of free reeds set in motion by rushing air.

Either way, by the early-19th century, tinkerers in Scandanavia and central Europe were toying with new instruments based on free reeds. In the 1820s, the earliest recognizable examples of the Mundharmonica, or “mouth organ,” were created in the renowned musical hubs of Berlin and Vienna. (In German, the word Harmonika refers to both accordions and harmonicas; the development of the two were tightly intertwined.) Most early models included one reed per hole, which limited the number of notes a musician could play.

But in 1825, an instrument maker named Joseph Richter designed a model that proved revolutionary—it fit two distinct notes into each hole, one produced during a drawn breath and one produced during a blow. Richter's design drastically extended the range of the compact instrument, and nearly two centuries later, it remains the reigning standard for harmonica tuning.

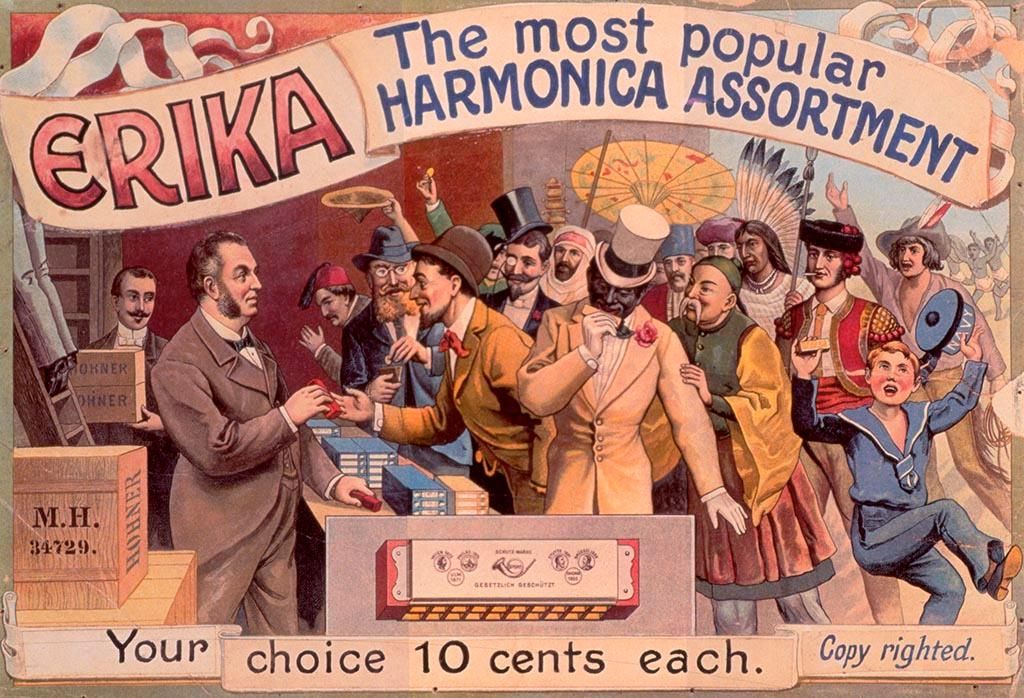

A good product needs a savvy salesman to match, however, and sales were slow in the harmonica's early years. Its greatest selling point—that it was relatively inexpensive and simple to play—was a disadvantage, too: as an instrument for the masses, it lacked respect among the European musical elite. Still, local manufacturers in central Europe began to toss their hats into the ring, founding small companies that competed for local markets. One of these men was Christian Messner, an enterprising resident of Trossingen in present-day Germany.

The firm Messner founded in 1827 was successful, if not overwhelmingly so, and his harmonicas were well-respected by the 1830s and 1840s. He was so conscious of his competition that he kept his construction methods a strict secret, allowing only members of the immediate family to know the workings of his factory.

This might sound a bit eccentric for a product that's now commonplace—harmonicas are the sort of instrument you keep in a pocket, not a padded case. Yet Messner was entirely right to worry, and in fact his caution wasn't enough. In the 1850s, when Messner's firm was enjoying its second decade of success, Messner's nephew, Christian Weiss, joined the family business. Weiss soon founded his own factory, and one day in 1856, one of Weiss' friends from school stopped by.

By the time that Matthias Hohner showed up at Weiss' doorstep, he was tired of eking out a living by wandering the Black Forest, selling wooden clocks. According to Hohner's diaries, the friendly visit to the factory lasted so long that Weiss not only grew suspicious—he threw young Hohner out. Yet by that point, Hohner had seen plenty. Just a year later, in 1857, he started a harmonica company of his own in a neighboring village.

It was the perfect time to be running a factory. Though musical instruments were traditionally made by hand, the late 19th-century saw the rise of powerful steam engines and early mass production techniques. Hohner made up for his relative lack of inexperience by studying existing harmonicas, producing them in huge batches, and selling for volume.

One of Hohner's shrewdest decisions was to look west, to the rapidly expanding market just across the Atlantic—the United States, where millions of largely working-class German immigrants served as the perfect conduit for his product. According to Martin Haeffner of the Harmonika Museum, the harmonica hitched a ride with European migrants to Texas, the South, and Southwest. There the harmonica became a key part of the emergent American folk music, including derivations of the spirituals that slaves had brought from Africa. Black musicians, both slaves and their descendants, were steeped in a diverse mix of music that proved the perfect incubator for new musical styles. They helped pioneer radically new styles of harmonica playing, like cross-harp, and in the process helped invent what we now know as blues harmonica. By the 1920s the harmonica stood alongside the guitar as an essential part of the blues, not to mention the companion of countless train-hopping wanderers and working-class performers.

After two decades in business, Hohner's company—which soon moved to Trossingen—was making 1 million harmonicas a year. Two decades after that, Hohner bought out the very company that had brought harmonicas to Trossingen, Christian Messner & Co. Like Messner, he kept the firm in the family, and under his sons, the Hohner brand became the Ford of accordions and harmonicas. Haeffner says that the city built its railroad and city hall using harmonica money. “For a long time, it was a Hohner city—a harmonica city,” he says.

Today, Trossingen is a town of 15,000, surrounded by farms and tucked into the eastern part of the Black Forest. Hohner has produced over 1 billion harmonicas. Many are imported from China, but Hohner makes its higher-end harmonicas in Trossingen with wood from local trees. To this day, the town's residents simply say die Firma—“the firm”—to refer to Hohner, the company that employed thousands of locals for much of the 19th- and 20th-century. Every other street seems to be named after either a musician or harmonica maker.

Every few months, for holidays and anniversaries, a few dozen residents gather in the Harmonika Museum, which is funded by German government grants and by Hohner Co. Its collection is currently being moved into the huge former Hohner factory, under Martin Haeffner's direction.

One day this summer, Haeffner gave a tour and invited folk musicians to play songs from Vienna. Local enthusiasts yammered over coffee and cake, debating the relative importance of harmonica greats like Larry Adler, Stevie Wonder, Bob Dylan and Little Walter. Once in a while, someone pulled out a shiny old Mundharmonika and played a few licks. For all the business savvy behind the rise of the harmonica, there's also something special about the instrument itself. “Maybe it's the way you make the sound. It's your breath,” says Haeffner. “You are very close to the music you make, and there's a lot of soul in it.”

The harmonica has traveled a long way—to America, to China, into orbit and back—but it never really left the little German town where its huge success began. “Every resident of Trossingen has a harmonica in their pocket,” one woman remarked. She rummaged around in her purse for a moment, before pulling out a four-hole harmonica and playing a tune. It was a Hohner “Little Lady,” the very same model that Wally Schirra snuck into space.