The Infamous “War of the Worlds” Radio Broadcast Was a Magnificent Fluke

Orson Welles and his colleagues scrambled to pull together the show; they ended up writing pop culture history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/cc/eecc4040-7e5f-4b5d-907f-b8b02db05a9b/be003721.jpg)

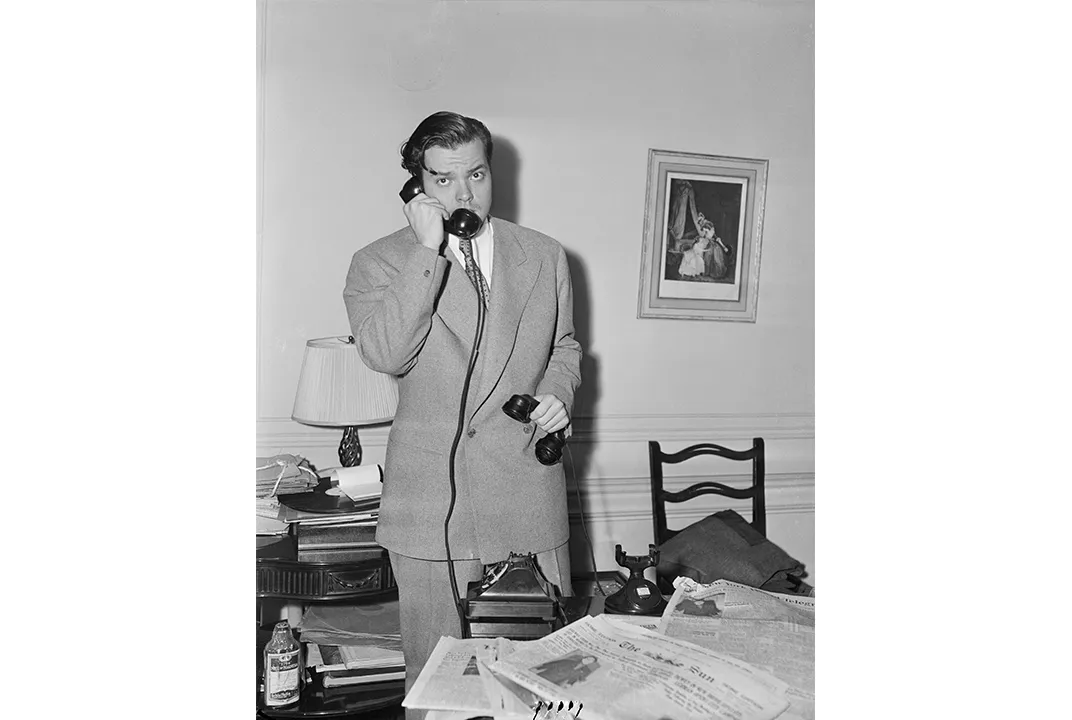

On Halloween morning, 1938, Orson Welles awoke to find himself the most talked about man in America. The night before, Welles and his Mercury Theatre on the Air had performed a radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, converting the 40-year-old novel into fake news bulletins describing a Martian invasion of New Jersey. Some listeners mistook those bulletins for the real thing, and their anxious phone calls to police, newspaper offices, and radio stations convinced many journalists that the show had caused nationwide hysteria. By the next morning, the 23-year-old Welles’s face and name were on the front pages of newspapers coast-to-coast, along with headlines about the mass panic his CBS broadcast had allegedly inspired.

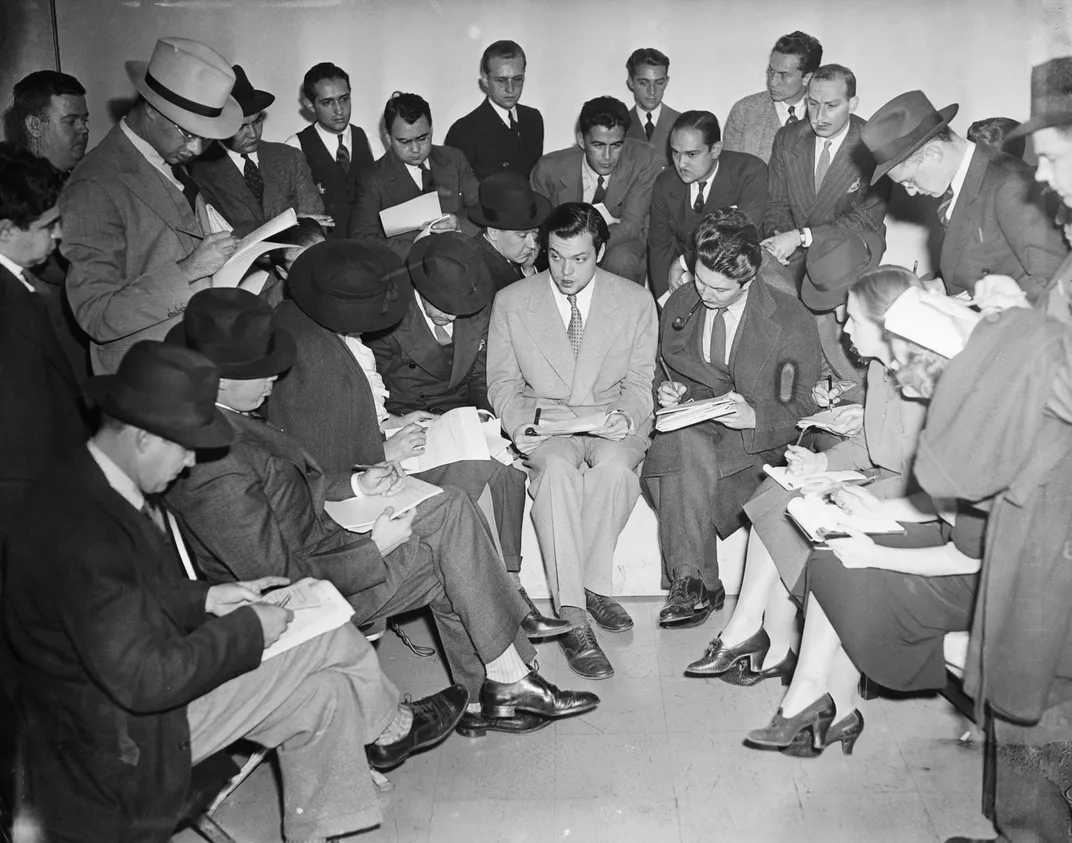

Welles barely had time to glance at the papers, leaving him with only a horribly vague sense of what he had done to the country. He’d heard reports of mass stampedes, of suicides, and of angered listeners threatening to shoot him on sight. “If I’d planned to wreck my career,” he told several people at the time, “I couldn’t have gone about it better.” With his livelihood (and possibly even his freedom) on the line, Welles went before dozens of reporters, photographers, and newsreel cameramen at a hastily arranged press conference in the CBS building. Each journalist asked him some variation of the same basic question: Had he intended, or did he at all anticipate, that War of the Worlds would throw its audience into panic?

That question would follow Welles for the rest of his life, and his answers changed as the years went on—from protestations of innocence to playful hints that he knew exactly what he was doing all along.

The truth can only be found among long-forgotten script drafts and the memories of Welles’s collaborators, which capture the chaotic behind-the-scenes saga of the broadcast: no one involved with War of the Worlds expected to deceive any listeners, because they all found the story too silly and improbable to ever be taken seriously. The Mercury’s desperate attempts to make the show seem halfway believable succeeded, almost by accident, far beyond even their wildest expectations.

* * *

By the end of October 1938, Welles’s Mercury Theatre on the Air had been on CBS for 17 weeks. A low-budget program without a sponsor, the series had built a small but loyal following with fresh adaptations of literary classics. But for the week of Halloween, Welles wanted something very different from the Mercury’s earlier offerings.

In a 1960 court deposition, as part of a lawsuit suing CBS to be recognized as the broadcast’s rightful co-author, Welles offered an explanation for his inspiration for War of the Worlds: “I had conceived the idea of doing a radio broadcast in such a manner that a crisis would actually seem to be happening,” he said, “and would be broadcast in such a dramatized form as to appear to be a real event taking place at that time, rather than a mere radio play.” Without knowing which book he wanted to adapt, Welles brought the idea to John Houseman, his producer, and Paul Stewart, a veteran radio actor who co-directed the Mercury broadcasts. The three men discussed various works of science fiction before settling on H.G. Wells’s 1898 novel, The War of the Worlds—even though Houseman doubted that Welles had ever read it.

The original The War of the Worlds story recounts a Martian invasion of Great Britain around the turn of the 20th century. The invaders easily defeat the British army thanks to their advanced weaponry, a “heat-ray” and poisonous “black smoke,” only to be felled by earthly diseases against which they have no immunity. The novel is a powerful satire of British imperialism—the most powerful colonizer in the world suddenly finds itself colonized—and its first generation of readers would not have found its premise implausible. In 1877, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli had observed a series of dark lines on the Martian surface that he called canali, Italian for “channels.” In English, canali got mistranslated to “canals,” a word implying that these were not natural formations—that someone had built them. Wealthy, self-taught astronomer Percival Lowell popularized this misconception in a series of books describing a highly intelligent, canal-building Martian civilization. H. G. Wells drew liberally from those ideas in crafting his alien invasion story—the first of its kind—and his work inspired an entire genre of science fiction. By 1938, The War of the Worlds had “become familiar to children through the medium of comic strips and many succeeding novels and adventure stories,” as Orson Welles told the press the day after his broadcast.

After Welles selected the book for adaptation, Houseman passed it on to Howard Koch, a writer recently hired to script the Mercury broadcasts, with instructions to convert it into late-breaking news bulletins. Koch may have been the first member of the Mercury to read The War of the Worlds, and he took an immediate dislike to it, finding it terribly dull and dated. Science fiction in the 1930s was largely the purview of children, with alien invaders confined to pulp magazines and the Sunday funnies. The idea that intelligent Martians might actually exist had largely been discredited. Even with the fake news conceit, Koch struggled to turn the novel into a credible radio drama in less than a week.

On Tuesday, October 25, after three days of work, Koch called Houseman to say that War of the Worlds was hopeless. Ever the diplomat, Houseman rang off with the promise to see if Welles might agree to adapt another story. But when he called the Mercury Theatre, he could not get his partner on the phone. Welles had been rehearsing his next stage production—a revival of Georg Buchner’s Danton’s Death—for 36 straight hours, desperately trying to inject life into a play that seemed destined to flop. With the future of his theatrical company in crisis, Welles had precious little time to spend on his radio series.

With no other options, Houseman called Koch back and lied. Welles, he said, was determined to do the Martian novel this week. He encouraged Koch to get back to work, and offered suggestions on how to improve the script. Koch worked through the night and the following day, filling countless yellow legal-pad pages with his elegant if frequently illegible handwriting. By sundown on Wednesday, he had finished a complete draft, which Paul Stewart and a handful of Mercury actors rehearsed the next day. Welles was not present, but the rehearsal was recorded on acetate disks for him to listen to later that night. Everyone who heard it later agreed that this stripped-down production—with no music and only the most basic sound effects—was an unmitigated disaster.

This rehearsal recording has apparently not survived, but a copy of Koch’s first draft script—likely the same draft used in rehearsal—is preserved among his papers at the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison. It shows that Koch had already worked out much of the broadcast’s fake news style, but several key elements that made the final show so terrifyingly convincing were missing at this stage. Like the original novel, this draft is divided into two acts of roughly equal length, with the first devoted to fake news bulletins about the Martian invasion. The second act uses a series of lengthy monologues and conventional dramatic scenes to recount the wanderings of a lone survivor, played by Welles.

Most of the previous Mercury broadcasts resembled the second act of War of the Worlds; the series was initially titled First Person Singular because it relied so heavily on first-person narration. But unlike the charming narrators of earlier Mercury adaptations such as Treasure Island and Sherlock Holmes, the protagonist of The War of the Worlds was a passive character with a journalistic, impersonal prose style—both traits that make for very boring monologues. Welles believed, and Houseman and Stewart agreed, that the only way to save their show was to focus on enhancing the fake news bulletins in its first act. Beyond that general note, Welles offered few if any specific suggestions, and he soon left to return to Danton’s Death.

In Welles’s absence, Houseman and Stewart tore into the script, passing their notes on to Koch for frantic, last minute rewrites. The first act grew longer and the second act got shorter, leaving the script somewhat lopsided. Unlike in most radio dramas, the station break in War of the Worlds would come about two-thirds of the way through, and not at the halfway mark. Apparently, no one in the Mercury realized that listeners who tuned in late and missed the opening announcements would have to wait almost 40 minutes for a disclaimer explaining that the show was fiction. Radio audiences had come to expect that fictional programs would be interrupted on the half-hour for station identification. Breaking news, on the other hand, failed to follow those rules. People who believed the broadcast to be real would be even more convinced when the station break failed to come at 8:30 p.m.

These revisions also removed several clues that might have helped late listeners figure out that the invasion was fake. Two moments that interrupted the fictional news-broadcast with regular dramatic scenes were deleted or revised. At Houseman’s suggestion, Koch also removed some specific mentions of the passage of time, such as one character’s reference to “last night’s massacre.” The first draft had clearly established that the invasion occurred over several days, but the revision made it seem as though the broadcast proceeded in real-time. As many observers later noted, having the Martians conquer an entire planet in less than 40 minutes made no logical sense. But Houseman explained in Run-Through, the first volume of his memoirs, that he wanted to make the transitions from actual time to fictional time as seamless as possible, in order to draw listeners into the story. Each change added immeasurably to the show’s believability. Without meaning to, Koch, Houseman, and Stewart had made it much more likely that some listeners would be fooled by War of the Worlds.

Other important changes came from the cast and crew. Actors suggested ways of reworking the dialogue to make it more naturalistic, comprehensible, or convincing. In his memoirs, Houseman recalled that Frank Readick, the actor cast as the reporter who witnesses the Martians’ arrival, scrounged up a recording of the Hindenburg disaster broadcast and listened to it over and over again, studying the way announcer Herbert Morrison’s voice swelled in alarm and abject horror. Readick replicated those emotions during the show with remarkable accuracy, crying out over the horrific shrieks of his fellow actors as his character and other unfortunate New Jerseyites got incinerated by the Martian heat-ray. Ora Nichols, head of the sound effects department at the CBS affiliate in New York, devised chillingly effective noises for the Martian war machines. According to Leonard Maltin’s book The Great American Broadcast, Welles later sent Nichols a handwritten note, thanking her “for the best job anybody could ever do for anybody.”

Although the Mercury worked frantically to make the show sound as realistic as possible, no one anticipated that their efforts would succeed much too well. CBS’s legal department reviewed Koch’s script and demanded only minor changes, such as altering the names of institutions mentioned in the show to avoid libel suits. In his autobiography, radio critic Ben Gross recalled approaching one of the Mercury’s actors during that last week of October to ask what Welles had prepared for Sunday night. “Just between us, it’s lousy,” the actor said, adding that the broadcast would “probably bore you to death.” Welles later told the Saturday Evening Post that he had called the studio to see how things were shaping up and received a similarly dismal review. “Very dull. Very dull,” a technician told him. “It’ll put ’em to sleep.” Welles now faced disaster on two fronts, with both his theatrical company and his radio series marching toward disaster. Finally, War of the Worlds had gained his full attention.

* * *

Midafternoon on October 30, 1938, just hours before airtime, Welles arrived in CBS’s Studio One for last-minute rehearsals with the cast and crew. Almost immediately, he lost his temper with the material. But according to Houseman, such outbursts were typical in the frantic hours before each Mercury Theatre broadcast. Welles routinely berated his collaborators—calling them lazy, ignorant, incompetent, and many other insults—all while complaining of the mess they’d given him to clean up. He delighted in making his cast and crew scramble by radically revising the show at the last minute, adding new things and taking others out. Out of the chaos came a much stronger show.

One of Welles’s key revisions on War of the Worlds, in Houseman’s view, involved its pacing. Welles drastically slowed down the opening scenes to the point of tedium, adding dialogue and drawing out the musical interludes between fake news bulletins. Houseman objected strenuously, but Welles overruled him, believing that listeners would only accept the unrealistic speed of the invasion if the broadcast started slowly, then gradually sped up. By the station break, even most listeners who knew that the show was fiction would be carried away by the speed of it all. For those who did not, those 40 minutes would seem like hours.

Another of Welles’s changes involved something cut from Koch’s first draft: a speech given by “the Secretary of War,” describing the government’s efforts to combat the Martians. This speech is missing from the final draft script, also preserved at the Wisconsin Historical Society, most likely because of objections from CBS’s lawyers. When Welles put it back in, he reassigned it to a less inflammatory Cabinet official, “the Secretary of the Interior,” in order to appease the network. But he gave the character a purely vocal promotion by casting Kenneth Delmar, an actor whom he knew could do a pitch-perfect impression of Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1938, the major networks expressly forbade most radio programs from impersonating the president, in order to avoid misleading listeners. But Welles suggested, with a wink and a nod, that Delmar make his character sound presidential, and Delmar happily complied.

These kinds of ideas only came to Welles at the last minute, with disaster waiting in the wings. As Richard Wilson observed in the audio documentary Theatre of the Imagination, radio brought out the best in Welles because it “was the only medium that imposed a discipline Orson would recognize, and that was the clock.” With the hours and then the minutes before airtime ticking away, Welles had to come up with innovative ways to save the show, and he invariably delivered. The cast and crew responded in kind. Only in these last minute rehearsals did everyone begin to take War of the Worlds more seriously, giving it their best efforts for perhaps the first time. The result demonstrates the special power of collaboration. By pooling their unique talents, Welles and his team produced a show that frankly terrified many of its listeners—even those who never forgot that the whole thing was just a play.

* * *

At the press conference the morning after the show, Welles repeatedly denied that he had ever intended to deceive his audience. But hardly anyone, then or since, has ever taken him at his word. His performance, captured by newsreel cameras, seems too remorseful and contrite, his words chosen much too carefully. Instead of ending his career, War of the Worlds catapulted Welles to Hollywood, where he would soon make Citizen Kane. Given the immense benefit Welles reaped from the broadcast, many have found it hard to believe that he harbored any regrets about his sudden celebrity.

In later years, Welles began to claim that he really was hiding his delight that Halloween morning. The Mercury, he said in multiple interviews, had always hoped to fool some of their listeners, in order to teach them a lesson about not believing whatever they heard over the radio. But none of Welles’s collaborators—including John Houseman and Howard Koch—ever endorsed such a claim. In fact, they denied it over and over again, long after legal reprisals were a serious concern. The Mercury did quite consciously attempt to inject realism into War of the Worlds, but their efforts produced a very different result from the one they intended. The elements of the show that a fraction of its audience found so convincing crept in almost accidentally, as the Mercury desperately tried to avoid being laughed off the air.

War of the Worlds formed a kind of crucible for Orson Welles, out of which the wunderkind of the New York stage exploded onto the national scene as a multimedia genius and trickster extraordinaire. He may not have told the whole truth that Halloween morning, but his shock and bewilderment were genuine enough. Only later did he realize and appreciate how his life had changed. As we mark the centennial of Welles’s birth in 1915, we should also remember his second birth in 1938—the broadcast that, because of his best efforts but despite his best intentions, immortalized him forever as “the Man from Mars.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/BradSchwartz0914-024_LowRes.jpg.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/BradSchwartz0914-024_LowRes.jpg.jpeg)