Inside the House of Zyklon B

An iconic Hamburg building, built by Jews and now a chocolate museum, once housed the distributors of one of Nazi Germany’s most gruesome inventions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/b9/20b9b2a4-81bf-4f91-9c10-c88722c15c7b/hamburg_meberghof.jpg)

The “chocoverse” of Germany is located inside a Hamburg building that is a shade of burnt brown with a hint of cinnamon on the exterior. The material is brick, yet evocative of a deconstructed layer cake crafted by a madcap pâtissier. Halvaesque limestone, discolored from age, stands in for the fondant-like décor: the tense buttresses rise and sprawl, sinew-like, up the walls. They tether several gargoyles of austere eeriness: a scaly seal, an armored mermaid, and, near the entrance, a skeletal death.

On the interior is the opulent filling: chiseled railing, frosted gold-leaf doors, glossy mahogany banisters weighed down by licorice-hued concrete frogs. Here, the chocolate manufacturer Hachez tempts tourists with its ground-floor museum and store, the Chocoversum.

But the building itself carries a link to Germany's darkest historical moment, far removed from sweetness of any sort.

The landmark exemplifies the ways in which architecture conceals—and reveals—disparate histories. The question here becomes: how to make them visible all at once?

Sifting through piles of sketches, the building’s architects, brothers Hans and Oscar Gerson, were blissfully unaware of this remote challenge. In the comfort of their homes, the two relished the bourgeois coziness of Germany under the rule of Wilhelm II. Away from this full-bodied domesticity, the rising stars of the Roaring Twenties and scions of an established Jewish family took joy in making brick sing entirely new harmonies. Their odes to humble burnt clay suited the taste—and the bill—of Hamburg’s chief urban planner Fritz Schumacher.

Completed between 1923 in 1924, the structure was the latest architectural fancy of northern Modernism; even the fastidious critic Werner Hegemann lauded its unfussy, “American” lines. It helped shape Hamburg’s striking commercial district, replacing the torn-down tenements that had incubated the city’s horrific cholera epidemic in 1892.

Hamburg, located along the Elbe River not far from where it empties into the North Sea, was Germany’s future “gate to the world.” A hub of commerce and banking, it had reared generations of Jewish entrepreneurs. From 1899 to 1918, Jewish shipping executive Albert Ballin oversaw the world’s largest passenger and trade fleet for the Hamburg-America Line (now HAPAG), dispatching goods and over 5.5 million hopeful immigrants overseas. An avowed opponent of World War I—trade blockades and military requisitioning of ships were no friends of maritime commerce—he took a deadly dose of sedative on November 9, 1918, the day when the Germany that he had known collapsed. The Gersons named their building Ballinhaus as a monument to the country’s late cosmopolite-in-chief. Outside, a relief captured Ballin's profile, and on the second floor, the company Albert Ballin Maritime Equipment opened a new office.

Another early tenant was the bank M. B. Frank & Co. The Great Depression had hit the company so hard that the founder’s heir, Edgar Frank, a onetime World War I volunteer and a patriotic “German citizen of Jewish faith,” carried on with only three employees and an income so negligible that it would go untaxed for several years. Alas, even a quick look outside made clear that finances were not his only problem. Hamburg and its suburbs were fast becoming battlegrounds for the emboldened Nazis and their only forceful opponents—Communists. As the two camps slugged it out on the streets—the Nazis would quickly begin winning most of the clashes—dark clouds gathered over the building’s Jewish owners and tenants.

Soon after the Nazis seized power in 1933, Max Warburg, offspring of the extended Jewish banker clan soon to preside over New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the American Ballet Company, resigned from the joint-stock enterprise in control of the building. Frank was intimidated into selling his business and all real estate. Unable to emigrate, he would be deported to Minsk, in the newly created Reichskommissariat Ostland, where he would die on March 8, 1942. In 1938 Ballin’s smashed relief landed in a garbage pile. Fully “Aryanized,” Ballinhaus was now Messberghof.

Designed by Jews, once named after a prominent Jew, and owned by Jews, the Gersons’ brick concoction was on its way to becoming a hub for facilitating the industrial murder of Jews.

Beginning in 1928, insecticide retailer Tesch & Stabenow took over the building step by step. First a modest neighbor of Albert Ballin Maritime Equipment, it slowly squeezed out the Jewish tenants, establishing itself as the largest distributor of the gas Zyklon B east of the Elbe. Between January 1, 1941, and March 31, 1945, according to the protocol of the British Military Court in Hamburg, company leaders, including its gassing technician, supplied “poison gas used for the extermination of allied nationals interned in concentration camps well knowing that the said gas was to be so used.” 79,069 kilograms of the substance were required in 1942 alone, 9,132 of them slated specifically to kill humans in Sachsenhausen, outside Berlin, its subcamp Neuengamme, near Hamburg, and Auschwitz. In 1943, the demand rose to 12,174 kilograms, and by early 1944, nearly two tons arrived in Auschwitz alone monthly.

Tesch & Stabenow did not actually produce Zyklon B or other gases widely used for disinfection. A subsidiary of the chemical company Degesch, with the nauseatingly saccharine name Dessau Sugar Refinery Works Ltd., made and packaged the goods in Germany’s east. Tesch & Stabenow then oversaw the shipping of the product and equipment to SS and Wehrmacht barracks, instructing the personnel about use on the proper enemy: lice, the main carriers of typhus. When asked for advice on mass extermination of Jews by the Nazi state, the company’s head Bruno Tesch suggested treating them like vermin by spraying prussic acid, the active ingredient in Zyklon B, into a sealed space. According to court testimony of his company’s various employees, from stenographers to accountants, Tesch proceeded to share the know-how in a hands-on manner.

According to the United States Holocaust Museum, at Auschwitz alone during the height of the deportations, up to 6,000 Jews were killed each day in the gas chambers.

Most of the Gersons were lucky to have escaped the Holocaust. Hans died of a heart attack in 1931. Oscar was excluded from the German Association of Architects and barred from practice in October 1933. His teenage daughter Elisabeth, intent on following in her father’s footsteps, kept changing schools as the discriminatory laws and regulations multiplied. In September 1938, the last school pressured her to drop out, recording her departure as voluntary.

The family fled to California, losing nearly everything to Germany’s extortionist Jewish Capital Levy, which taxed the Jewish immigrants’ assets at up to 90 per cent. In Berkeley, Oscar was eventually able to secure several residential commissions, and the town’s plaque speaks of a fulfilling career stateside. And yet, the restitution records filed between 1957 and 1966 show that the American projects were no match for his potential—or for Elisabeth’s, who had to make do vocational training, paying her way through a Californian community college and resigning herself to the commercial artist jobs that would leave her talents untapped for life.

Nothing around Hamburg’s Messberghof today tells these stories. Of course, this isn’t to say that the building goes unmarked: it boasts two different plaques. Tellingly, they appear on its two different sides, as if history’s chapters did not belong in the same continuous narrative. Neither can a visitor spot them from the entrance to Chocoversum’s sweet-tooth paradise. Instead, the vicissitudes of modern-day remembrance err helplessly between death and death by chocolate.

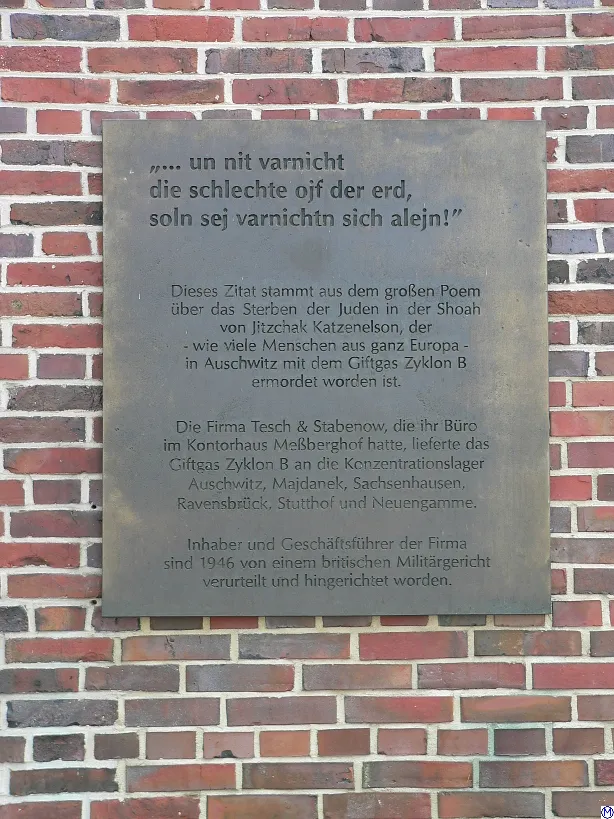

The first plaque describes Messberghof’s architectural merits, as befits a Unesco World Heritage Site, which the entire commercial district became in 2015. The second records Tesch & Stabenow’s crime and punishment and recalls its victims, among them the poet Itzhak Katzenelson, murdered in Auschwitz. “Destroy not the villains in the world,” a quote from him reads in transliterated Yiddish, “let them destroy themselves.”

Taking notes for his recent book about postwar Allied tribunals, the author A. T. Williams shuffled off unimpressed by this “paltry memorial.” The storm preceding its dedication in June 1997 may have escaped him. All through the early 1990s, local history preservation activists fought the German Real Estate Investment Co., which managed the building and worried that the footnote to its historical burden would scare away potential renters. The administrators vehemently opposed the design with an image of a Zyklon B container. Too reminiscent of Warhol’s Campbell Soup can, they sanctimoniously pronounced, appearing to sidestep probing questions about historical memory. The building’s owner, Deutsche Bank, weighed in. “Your suggestion to picture the Zyklon B container on a plaque,” its senior vice president Siegfried Guterman responded to the activists in the spring of 1996, “has something macabre about it.” What if, he feared, it “elevate[s] the thing to the status of an art object”? The activists’ bitter quip that nothing could be more macabre than the Holocaust fell on deaf ears, as did the plea to restore the original name, Ballinhaus. These memory wars, too, go unrecorded for the tourist.

The death gargoyle at the entrance to the Gersons’ “American” edifice has turned out to be uncannily prescient. Peering at it in the knowledge of the layered history did more than simply give goosebumps; it suffocated. The effects seemed almost physical. I was in Hamburg to research the early life of Margret and H. A. Rey, the famous children’s book authors and the Gersons’ relatives and close friends. Already a few days in, the archival forays revealed every anticipated shade of darkness. By day, I would peruse the extended family’s restitution files—the postwar West German government’s complicated and sluggish payouts for the Nazi wrongs and, tragically, the most extensive source of knowledge about Germany’s Jews under and after Nazism.

At night, by an odd coincidence, I would lay sleepless across the street from the building where the British Military Court had sentenced Bruno Tesch to death on March 8, 1946, making him the only German industrialist to be executed. Sprawled in the once predominantly Jewish quarter Eimsbüttel, the art noveau gem stood just around the corner from where H. A. Rey had gone to school. In front of the school, now the university library, was the square where the Nazis rounded up Hamburg’s Jews, banker Edgar Frank among them, for deportations starting October 1941. In the pavement, multiples of Stolpersteine, the bronze cobblestone-sized mini-monuments with the names and fates of the perished residents, gave off threnodial glimmer. The city seemed haunted by the ghosts of those whom it had rejected and sent to die. Someday, they will return to claim their share of Messberghof’s memories.