This Interactive Map Visualizes the Queer Geography of 20th-Century America

Mapping the Gay Guides visualizes local queer spaces’ evolution between 1965 and 1980

:focal(761x586:762x587)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/4d/514d6c4e-f66a-43ec-9a03-8b3e55e281b4/graphic_new.jpg)

At first glance, Bob Damron’s Address Book reads like any other travel guide. Bars, restaurants, hotels and businesses are grouped by city and state, their names and addresses listed in alphabetical order. An introductory note reassures readers that the information contained within the volume is up-to-date, while classifications written in abbreviated parentheticals offer travelers additional details on specific establishments: An asterisk, for example, indicates a place is “very popular,” while the letter “D” specifies if a bar or club has space for dancing.

Ostensibly universal, Damron’s handbook, first published in 1964 and still released annually, was actually directed toward a specific—and secretive—audience. As Eric Gonzaba, a historian at California State University, Fullerton, explains, Damron, a white, gay man from San Francisco, “started just writing down lists of locations that he would visit, … places [where] he either found other gay men or he felt accepted.”

What began as a personal reference for the Californian and his friends soon morphed into a thriving enterprise akin to The Negro Motorist Green Book, which safely shepherded African American travelers across the country during the Jim Crow era, but for gay men and, to a lesser extent, lesbian women. Crucially, Damron’s Address Book never explicitly identified its target audience (at least until 1999, when the word “gay” was first printed on its cover), instead relying on euphemisms, innuendo and coded abbreviations to circulate information within the queer community.

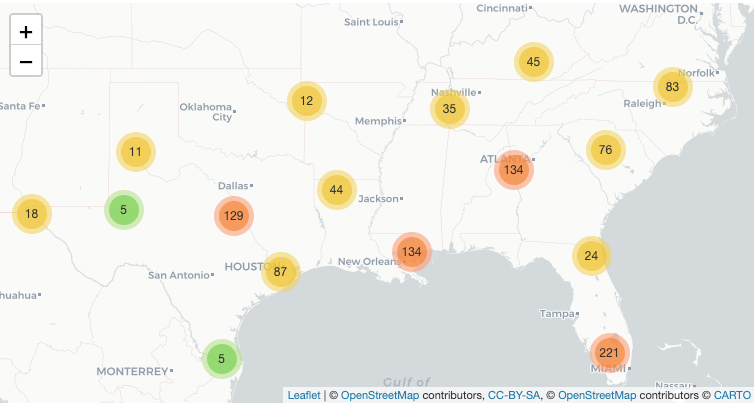

A new public history initiative spearheaded by Gonzaba and Amanda Regan, a historian at Southern Methodist University, is poised to bring Damron’s findings into the digital age, drawing on more than 30,000 listings compiled between 1965 and 1980 to visualize queer spaces’ evolution over time. Titled Mapping the Gay Guides, the project aims to “correct the cultural erasure of historical geography” by spotlighting local communities’ oft-unheralded queer history and, adds Gonzaba, exploring “how that community relates to other parts of the country.”

The first phase of Mapping the Gay Guides launched in mid-February with a focus on the southern United States. Site visitors can browse some 7,000 entries, filtering by year; geographic location; type (among others, cruising areas, book stores, and bars or clubs); and “establishment feature,” a term coined by the researchers to describe the abbreviated designations used in Damron’s original text. Vignettes accompanying the interactive map provide historical context on the data, lending the portal what Regan calls a “layered perspective”; sections on methodology and ethics offer insights on the project’s technical side and the fraught decision-making involved in transforming a historical document into a data set. Interns and graduate students helped the researchers organize this vast trove of data, transcribing text from digitized images of the guide and rendering the entries machine-readable. The students also aided in tracking down and verifying various establishments’ locations.

Mapping the Gay Guides isn’t the first digital history project dedicated to Damron’s Address Books or the numerous spin-off guides the publications spawned. But it differs from the majority of these resources in its scope—most portals focus on a specific city or region, not the entire country—and use of a single source rather than multiple. As Gonzaba explains, “This is one publisher and one guy’s view of what the gay world looked like.”

In 1964, the year Damron first published his Address Book, gay sex was considered a crime in every state except Illinois, and the Stonewall Uprising, widely credited with sparking the contemporary gay rights movement, was still five years away. To ensure his work reached its intended audience, Damron plugged into existing networks within the underground gay community, adding his handbook to the array of erotica, pulp novels, physique magazines and other printed materials available to those in the know. Per Gonzaba, Damron also sent guides to establishments featured in the text so they could sell copies to patrons.

“The minute you enter the gay world via one of these sites,” says Gonzaba, “ … you can possibly buy access to even more of the gay culture, [identifying] more spaces by buying this guide and being able to see other places that might be of interest to you in other cities.”

According to Los Angeles magazine’s Kate Sosin, Damron visited 200 cities across 37 states in the first year of publication alone. Almost every year thereafter, he released at least one new edition of the guide, adding entries submitted by readers and revising existing listings based on his trips back to the places mentioned. In some cases, he removed businesses because police crackdowns had rendered them unsafe for queer visitors.

Damron’s Address Books weren’t the only gay travel guides available during the latter half of the 20th century, but as Mapping the Gay Guides points out, “They were the original and remained the gold standard, especially for men, through the 1990s.”

In 1985, Damron sold his company to Dan Delbex, a friend of current owner Gina Gatta, who published the 52nd edition of the guide last year. Six years later, he died from complications of HIV.

Much about the man himself—including the nature of the job that made him traverse the country—remains enigmatic. But by identifying patterns in the body of work Damron left behind, the researchers hope to learn more about his individual character, including the implicit biases he had as a gay, white man from the progressive coastal city of San Francisco.

According to Gonzaba, Damron often classified sites popular among gay African American men in the American South as not only “B” (“Blacks Frequent”), but “RT,” or “Raunchy Types”—shorthand for establishments deemed “less than reputable.” Moving forward, the team plans on determining whether Damron repeated this pairing in listings for other regions of the country or limited its use largely to the southern states, which he appears to have viewed from a coastal perspective as “wholly unsafe for queer people.”

“Is this a trend only in the South,” asks Gonzaba, “or does Damron conflate black spaces with spaces of vice, spaces of unsafety, spaces of deviancy?”

Mapping the Gay Guide’s main function is preserving and publicizing an overlooked, under-studied chapter in LGBTQ history. As outlined on the project’s homepage, few of the businesses detailed in the Address Books remain in existence today. Largely omitted from the historical record, the presence of bars, bathhouses and informal cruising locations is easily forgotten, rendering the “queer history of local communities [seemingly] invisible or nonexistent.”

Damron’s guidebooks refute this misconception, testifying to the existence of what Gonzaba deems “thriving” gay communities in cities across the country long before Stonewall and other milestones in the gay rights movement. The texts, though clearly aimed at a male audience, also hint at the growth of lesbian communities: The number of sites labeled “G” (“Girls, but seldom exclusively”) jumps from 3 in 1965 to 98 in 1980.

On a wider scale, says David Johnson, author of Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepeneurs Sparked a Movement, to Los Angeles magazine, the Address Books likely contributed to the growth of a collective sense of gay identity.

“They helped knit the community together in a national way,” explains Johnson. “So it’s no longer just, you go to your local bar, but wherever you are, if you’re traveling to a big city from a small town, you can find the community.”

By fall 2020, the Mapping the Gay Guides team hopes to publish listings from every state, Washington, D.C., Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. The researchers will also continually update the site’s “Vignettes” section.

In terms of anticipated audience, the project aims to appeal to a broad base of readers.

“We want this mapping project to be used by public historians, by tour guides, by local museum docents,” says Gonzaba. “… We’re hoping that by introducing these maps and these listings to places like Savannah, Georgia, or Beaumont, Texas, or somewhere in Montana, that you can add queer history to the places where people say queer history doesn’t exist.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/60/6560be64-0d0d-4111-bf77-e9592262ad4a/screen_shot_2020-03-05_at_45952_pm.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)