The Intergalactic Battle of Ancient Rome

Hundreds of years before audiences fell in love with Star Wars, one writer dreamt of battles in space

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/41/aa4163fc-5858-4be8-8023-ded44b977eb8/spiders-in-space-wr.jpg)

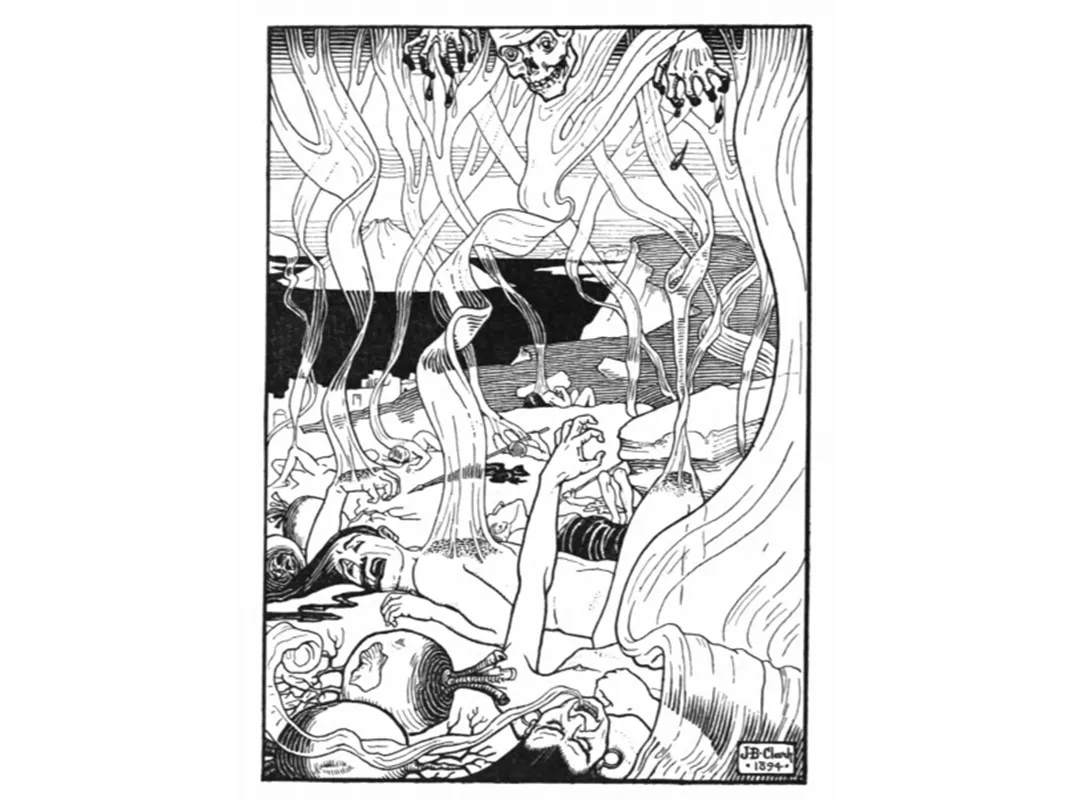

A long time ago, in a world not so far away, a young man who longed for adventure was swept up in a galactic war. Forced to choose between two sides in the deadly battle, he befriended a group of scrappy fighters who captained… three-headed vultures, giant fleas and space spiders?

Nearly 2,000 years before George Lucas created his epic space opera Star Wars, Lucian of Samosata (a province in modern-day Turkey) wrote the world’s first novel featuring space travel and interplanetary battles. True History was published around 175 CE during the height of the Roman Empire. Lucian’s space adventure features a group of travelers who leave Earth when their ship is thrown into the sky by a ferocious whirlwind. After seven days of sailing through the air they arrive on the Moon, only to learn its inhabitants are at war with the people of the Sun. Both parties are fighting for control of a colony on the Morning Star (the planet we today call Venus). The warriors for the Sun and Moon armies travel through space on winged acorns and giant gnats and horses as big as ships, armed with outlandish weapons like slingshots that used enormous turnips as ammunition. Thousands die during the battle, and blood “[falls] upon the clouds, which made them look of a red color; as sometimes they appear to us about sun-setting,” Lucian wrote.

After the war’s conclusion, Lucian and his friends continue traveling through space, learning about the Moon’s odd inhabitants (an all-male society, whose anatomy included a single toe instead of a whole foot and children cut from their calves) before moving on to visit the Morning Star and other space cities.

Lucian was more of a satirist than a novelist; True History was written as a critique of philosophers and historians, and their ways of thinking about new discoveries. As scholar Roy Arthur Swanson writes, Lucian’s work provided “the perennially necessary reminder that thinking and believing are different and distinct kinds of mental activity and that it is best not to confuse them.”

But being a work of satire doesn’t preclude True History from joining the ranks of science fiction. In addition to showing first contact, wars in space, and a flight to the moon, the work’s satirical nature is actually yet another thing it has in common with the genre’s modern form.

“One of the consistent themes of sci-fi is satire, and making fun of the way humans live and run the world,” says Aaron Parrett, professor of English at University of Great Falls in Montana. “That is one reason why Lucian is so important. He did that very thing.”

Lucian was also likely aware of major scientific and philosophical research of his time, including Plutarch’s “On the Face in the Orb of the Moon,” and Ptolemy’s last recorded observation of the planets, which occurred 14 years prior to Lucian’s publication. Still, the astronomical telescope wasn’t invented until 1610, and Lucian’s narrative doesn’t feature scientifically sound space travel. Does that mean it doesn’t count as an early form of the genre?

It depends who you ask. Douglas Dunlop, who works as a metadata librarian at Smithsonian Libraries, sees parallels between Lucian’s writing and that of the later science fiction writers like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells.

“Just because it doesn’t have what we would call ‘modern science’ doesn’t take away from the fact that [philosophy and natural sciences] influenced the writing,” Dunlop says. “There was a theory called Plurality of Worlds that goes back to Greek Antiquity, which was the concept of life existing in space. So who’s to say what they were doing in their philosophy and observation wasn’t informing their understanding of the world around them?”

Other literary scholars have posited the world of science fiction starts with the Epic of Gilgamesh (2100 B.C.), Frankenstein (1818), or the works of Jules Verne (1850s). For famous American astronomer Carl Sagan, sci-fi starts with Johannes Kepler’s novel Somnium (1634), which describes a trip to the moon and the view of Earth seen from far away. But Kepler, as it turns out, was partially inspired by Lucian. He picked up True History in the original Greek to master the language. (While Latin was the vernacular of ancient Rome, Greek was the language used by the educated elite.) He wrote that his studies were improved by his enjoyment of the adventure, and it seems to have sent his imagination spinning as well. “These were my first traces of a trip to the moon, which was my aspiration at later times,” Kepler wrote.

Genre requirements aside, both True History and Star Wars offer ways of understanding and exploring the human world, even though the stories take place in the stars.

“One of the great things that science fiction does as a way of changing people’s worldview is show what the world might be like,” Parrett says. “It’s remarkable that people dreamed up things long before there was any possibility that they could do it. This is true not just of flying to the moon, but of flying in general.”

Lucian may never have believed humans would achieve flight to the moon—but he imagined it. And the path he laid for intergalactic stories continues to send writers, scientists and movie-goers dreaming of what might be out there, just beyond our reach.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)