The International Vision of John Willis Menard, First African-American Elected to Congress

Although he was denied his seat in the House, Menard continued his political activism with the goal of uniting people across the Western Hemisphere

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/92/bc923044-3abf-403c-99f3-c0ba0c794e01/john-willis-menard-wr2.jpg)

In July 1863, months after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, a young African-American man from Illinois boarded a small ship in New York City and headed for Belize City, in what was then British Honduras. John Willis Menard, a college-educated political activist born to free parents of French Creole descent, made his Central American journey as a representative of Lincoln’s. His goal: to determine whether British Honduras was a suitable location for previously enslaved Americans to relocate.

Menard’s trip to Central America was undoubtedly an unusual period in his early political career—one that never came to fruition—but it set the stage for decades of internationalism. Wherever he moved and whatever position he held, Menard repeatedly considered African-American liberation in the context of the New World’s dependence on the work of enslaved laborers.

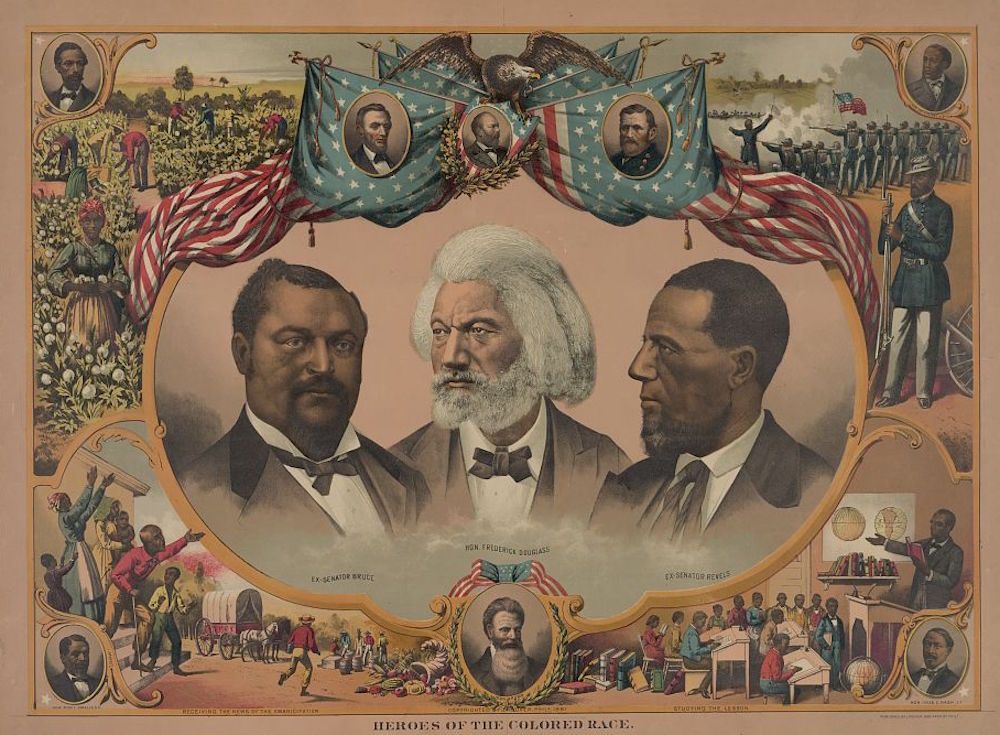

That work, and Menard's brief foray into the world of legislation, is part of what makes his appearance in a newly digitized photo album so remarkable. The album, acquired by the Library of Congress and Smithsonian's National Museum of African-American History and Culture last year, features rare portraits of dozens of other abolitionists of the 1860s, including Harriet Tubman and only known photo of Menard (shown above). While those photos offer unique insight into the community of abolitionists fighting for a better future for African-Americans, what they don't show is the controversy that sometimes surrounded that debate.

Before the American Civil War came to its bloody end, both Lincoln and the growing community of free black Americans were looking ahead to a United States without slavery. There were around 4 million enslaved people in the United States in 1860, comprising 13 percent of the American population. What would happen when all of them were freed?

“A number of African-American leaders saw colonization to Central America, to Mexico, or to Africa as the only viable solution prior to the Civil War,” says historian Paul Ortiz, author of Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920.

For more than a year, President Lincoln had publicly expressed his support for the colonization efforts of emancipated African-Americans. He’d had discussions about colonization with representatives from the government of Liberia, as well as members of the Cabinet. He even espoused his views on colonization to leading members of the African-American community.

“You and we are different races,” Lincoln told a black delegation invited to the White House in August 1862. “Even when you cease to be slaves, you are yet far removed from being placed on an equality with the white race. It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated.”

“Lincoln was relatively devoid of personal prejudice, but that doesn’t mean that he didn’t incorporate prejudice into his thinking,” writes Oxford University historian Sebastian Page. After the fall congressional elections of 1863, historians argue that Lincoln “came to appreciate the impracticality, even immorality of expatriating African-Americans who could fight for the Union.”

While some members of the free African-American community initially supported Lincoln’s colonization plan—11,000 moved to Africa between 1816 and 1860—many more were vocal in their opposition. Among the most vehement critics was Frederick Douglass. As historian Eric Foner writes in The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, “Douglass pointed out that blacks had not caused the war; slavery had. The real task of a statesmen was not to patronize blacks by deciding what was ‘best’ for them, but to allow them to be free.”

But Menard could be just as voluble in his defense of the colonization plan. “This is a white nation, white men are the engineers over its varied machinery and destiny,” Menard wrote to Douglass in 1863. “Every dollar spent, every drop of blood shed and every life lost, was a willing sacrifice for the furtherance and perpetuity of a white nationality. Sir, the inherent principle of the white majority of this nation is to refuse forever republican equality to the black minority. A government, then, founded upon heterogeneous masses in North America would prove destructive to the best interest of the white and black races within its limits.”

And so Menard traveled to Central America. American companies with business interests in the region made it one possible option for colonization. While there, Menard noted the potential of the landscape for a colony of newly freed African-Americans, but also worried over the absence of housing and proper facilities. Although Menard announced his support for a colony in British Honduras and wrote a favorable report to Lincoln upon returning in the fall of 1863, he worried about lack of support for such a project. As historians Phillip Magness and Sebastian Page write in Colonization After Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement, “Menard, long among the most vocal supporters of Liberian migration [to Africa], conceded that he was torn between resettlement abroad and working to improve the lot of blacks at home.”

Ultimately, the Union victory in the Civil War in 1865 and the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 made the latter option more possible than it ever had been before. In 1865 Menard moved to New Orleans, where he worked among the city’s elite African-Americans to fight for political representation and equal access to education. When James Mann, a white congressman from New Orleans, died five weeks into his term in 1868, Menard successfully ran for the seat and became the first African-American elected to Congress.

Despite Menard winning the clear majority of votes in the election, his opponent, Caleb Hunt, challenged the outcome. In defending the fairness of his victory to the House of Representatives, Menard also became the first African-American to address Congress in 1869. “I have been sent here by the votes of nearly nine thousand electors, [and] I would feel myself recreant to the duty imposed upon me if I did not defend their rights on this floor,” Menard stated. But the Republican-majority House of Representatives refused to seat either Menard or Hunt, citing their inability to verify the votes in the election.

Menard refused to give up on his vision of a democratic future for African-Americans—or forget his early lessons in the importance of building international relationships. In 1871 he moved to Florida with his family, this time taking up his pen to describe the work by immigrants and African-Americans to produce representative democracies at a local level. Menard edited a series of newspapers, and moved from Jacksonville to Key West, where he could participate in an almost utopic community, says Ortiz.

“Menard had a black, internationalist vision of freedom. That’s why he ends up describing Key West with such excitement,” Ortiz says. At the period, the island community was filled with a mixture of working class white people, as well as immigrants from Cuba, the Bahamas and elsewhere in the Caribbean. “Part of his genius was that he understood the freedom of African-Americans in the United States was connected to those freedom struggles in Cuba and Central America.”

Menard wasn’t the only one interested in building a coalition across racial and linguistic lines. During the same period, multiple states passed Alien Declarant Voting laws, allowing new immigrants to register to vote as long as they promised to become naturalized citizens. Menard wrote of political events conducted in both English and Spanish, Ortiz says, adding that Menard was representative of other black leaders who saw politics in a new way—as a system of power that impacted people regardless of national borders.

But for all his work in Florida, and later in Washington, D.C., Menard eventually came up against the system of oppression that Reconstruction-era policies failed to undo. Violent white supremacist groups like the Knights of White Camellia and the White League formed to terrorize African-Americans and prevent them from voting. Deadly attacks occurred across the South, from the Colfax Massacre in New Orleans to the Ocoee Massacre in Florida.

“The tragedy is, we know the end of the story,” Ortiz says of Menard’s attempt to create lasting change for his community and others. “Those movements were defeated. White supremacist politics were premised on everything being a zero-sum game. Economic resources, jobs, the right to even claim that you were an equal person. Reconstruction was beginning to work, and what came after it didn’t work. It’s our tragedy to live with.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)